The artist Mark Dion brings environmental science outside of the laboratory and into the museum, by crafting large-scale installations and fantastical cabinets modeled after Wunderkammern of the sixteenth century. These cabinets of curios often feature unusual orderings of objects and specimens collected from staged digs and excursions, and address topics ranging from environmentalism to public policy. Dion rose to prominence in the 1990s, and since then, has only become more relevant as threats to environmental protection become increasingly dire.

In this excerpt from Phaidon’s monograph Mark Dion , the artist speaks with noted historian and curator Miwon Kwon. The two discuss how Dion came to make work about the environment (spoiler alert: he had an enlightening experience while taking a dump in the rain forest), about the inherent contradictions within 'green' environmentalism, and about how global economies and colonialism are often best represented by the natural world.

Was your move to New York in 1982 a beginning point of sorts?

This might sound kind of formulaic, but I’d say there were three major stages to my not so sentimental education. The first was attending the Art School of the University of Hartford, which was a giant leap for me considering my working-class background. My folks were intelligent and supportive, but coming from a small coastal town across the river from the industrial seaport of New Bedford, Massachusetts, I grew up with almost no access to fine art. I was eighteen before I saw my first art exhibition—Chardin—in Boston. After two minutes at the Hartford Art School, I realized just how ignorant I was about art. So in addition to my classes, I got a job as an assistant in the slide library and asked a lot of questions.

The next stage was moving to New York and attending the School of the Visual Arts and then the Whitney Independent Study Program. There I met many of my best friends and extremely generous teachers like To Lawson, Craig Owens, Martha Rosler , Joseph Kosuth, Barbara Kruger , and Benjamin Buchloh. They were amazingly smart, tough, and fiercely protective of all of us when we needed it. The third stage took the form of my travels into the forests of Central America. That led to my renewed interest in the biological sciences, which I studied at home and at the City College of New York.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Go On a New York City Scavenger Hunt With Artist Mark Dion

It’s one thing to see the art world as a fascinating place of new ideas and another to believe that you have something meaningful to say in that world or engage it in a productive dialogue. When did that shift occur?

By the time I got out of the Whitney Program in 1985, I sort of knew how to be an artist, because I had been provided with dozens of different models of what artists do and how they do it. But I hadn’t figured out where or how I was going to apply the conceptual tools I had acquired. That came much later when I returned to what I was initially interested in long before school: environmentalism, ecology, and ideas about nature. In the slick world of Conceptual and media-based art of the early 1980s, no one seemed interested in problems of nature. So it took me some time to get back to it as a viable area for critical and artistic investigation. I had a lot of unlearning to do also.

Can you talk a bit about your early institutional critique projects coming out of the School of Visual Arts and the Independent Study Program?

During my studies, Gregg Bordowitz and I were very close, and we hashed out a lot of ideas together, especially those concerning art and its possibilities. At the time, we were excited by the debates around documentary—the problematics of telling the ‘truth.’ We were focused on film: the work of Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin in particular, as well as Peter Wollen, Laura Mulvey and Chris Marker, and the photography of Allan Sekula, Martha Rosler, and others. These people had an enormous influence on us as we tried to imagine an expanded documentary practice. While the belief in truth as unmediated authenticity had waned, there still remained the task of describing the world. Some of my early projects like This Is a Job for FEMA, or Superman at Fifty (1988), I’d Like to Give the World a Coke (1986), and Toys ‘R’ U.S. (1986) were attempts to translate critical strategies from the field of documentary film and photography to an installational or sculptural field.

How did such concerns lead to what you’re known for now, which is an art that deals with cultural representations of nature?

It came about as a result of living a dull life. In my ‘work’ time, I was doing grueling research to develop various installations like Relevant Foreign Policy Spectrum (From Farthest Right to Center Right) (1987) and others. In my ‘off’ time, I continued to pursue my interest in nature, adding to my personal collections of insects and curiosities, taking trips to the tropics, beaches, salt marshes in Long Island or natural history museums. It wasn’t until I began reading a lot of nature writing and scientific journalism that I stumbled onto Stephen Jay Gould, who opened up a huge window for me. Here was someone applying the same critical criterion implicit in the art I aspired to make—which can loosely be described as Foucaultian—to problems in the reception of evolutionary biology. It became very to clear to me that nature is one of the most sophisticated arenas for the production of ideology. Once I realized that, the wall between my two worlds dissolved.

So what projects followed that revelatory moment?

The first works were the Extinction series, Black Rhino, with Head (1989) and Concentration (1989), which explored the problems of environmental disruption in relation to colonial history. It was in these works that I first made use of the shipping crate as a way of addressing the international traffic of material and ideologies and myself. These works were made for shows in Belgium, which has a particularly pernicious relation to Africa as well as a disregard for the issues of animal importation and endangered species protection. In both works I was looking at a complex system, trying to examine how the current loss of biological diversity through extinction could be seen as a protracted effect of colonialism, the Cold War, and ‘Band-Aid’ development schemes. Collaborations with Bill Schefferine, like Under the Verdant Carpet, also pointed to the impossibility of untangling any single strand from a web of relations; here we literally compacted ideas on top of each other in a way that mirrored that entanglement.

During my travels in the Central American tropics, I became very concerned with the natural and cultural problems of tropical ecology. On my first visit to a tropical rainforest, I was overwhelmed by its complexity and beauty. The alienness of the jungle, its awesome vitality—I was so impressed. I remember taking a shit during a hike in the bush and having titanic dung beetles and a dozen different flying insects descending down on it before I could get my pants up. What a place!

Anyway, even though they make up only 6-7% of the earth’s land mass, tropical rainforests contain well over half of all living species. They are amazing laboratories of evolution, the greenhouses of biological diversity. At the same time, they are enormously affected by postcolonial politics, global economics, sovereignty issues and northern fantasies of paradise and green-hell. In the 1980s, tropical forest debate were like a microcosm of the deepening divide between countries of the northern and southern hemispheres. They were also a map of our assumptions, desires and projections about what constitutes nature.

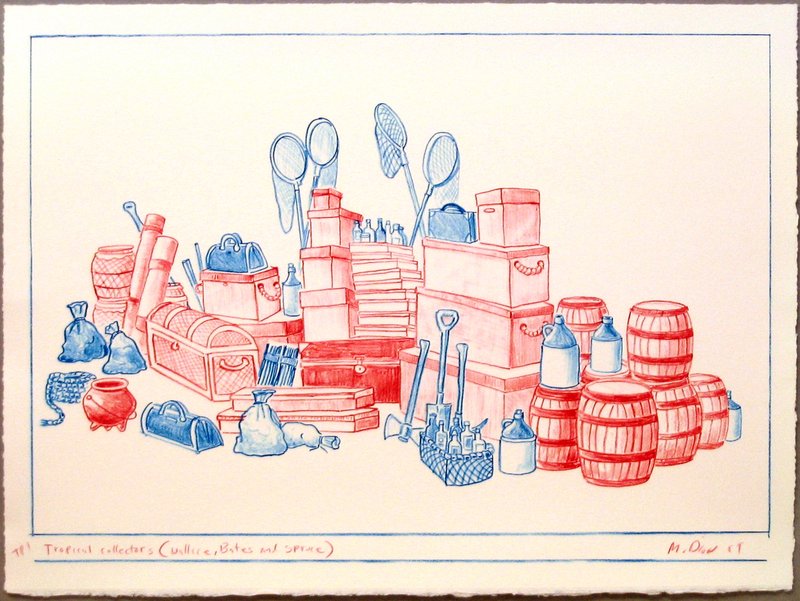

Topical Rainforest Preserves (Mobile Version), from 'Wheelbarros of Progress"

, with William Schefferine (1990)

Topical Rainforest Preserves (Mobile Version), from 'Wheelbarros of Progress"

, with William Schefferine (1990)

What did you think an artist or an artwork could do in the face of such conditions?

What a question! Well, one of the fundamental problems is that even if scientists are good at what they do, they’re not necessarily adept in the field of representation. They don’t have access to the rich set of tools, like irony, allegory, and humor, which are the meat and potatoes of art and literature. So this became an area of exploration for Schefferine and me. Also, the ecological movement has huge blindspots in that it is extremely uncritical of its own discourse. At the time, it was evoking images of Eden and innocence, calling for a back-to-nature ethos. So part of what we did was critique these ideologically suspect, culturally entrenched ideas about nature.

The parade Schefferine and I made for American Fine Arts, Co., in New York called The Wheelbarrows of Progress, was largely a response to the shockingly bone-headed ways of thinking which we witnessed around ‘green’ issues. Each wheelbarrow carried a weighty folly—from the Republican dismantlement of the renewable energy program, to wildlife conservation groups pandering to the public with pandas.

Tropical Rainforest Preserves (1990) is a good example of a response to a double phenomena. On the one hand, zoos in North America were creating rainforests inside cities as special exhibits. On the other hand, ecological groups were trying to export notions of a national park—locking up natural resources in order to protect them. Our piece was meant to reflect on such conditions in a humorous way by making an absurdly small reserve that was ‘captured’ and mobile, comically domesticated and reminiscent of the Victorian mania for ferns, aquariums, and dioramas.

What is your assessment of such projects in hindsight? To me, they seem very didactic.

I think our projects were more complex than they may have seemed at first glance, less didactic than they appeared. They never spoke monolithically, and often had counter-arguments built into them. For instance, Selections from the Endangered Species List (the Vertebrata) or Commander McBrag Taxonomoist (1989) tried to visualize two different processes that have a dialectical relationship to one another—the task of naming animals as one ‘discovers’ them (as in Linnaeus) and naming animals as they die off and disappear (as in the endangered species list). It’s like Noah hunting down all the animals he saved on the ark. We wanted our work to convey the reality of contradictions like that. Moreover, all the works contained massive amounts of detail and layering. Perhaps they were didactic, but at least they weren’t boring. Humor was an important factor to the success of these works.

In the early 1990s, the New York art world classified your practice under the banner of ‘green’ art. But it seems you’ve moved away from overt references to eco-politics in favor of studies of cultural institutions, specifically the natural history museum, as well as particular modes of display, such as curiosity cabinets.

I think the politics of representation as it involves the museum has always been part of my practice. As I see it, artists doing institutional critiques of museums tend to fall into two different camps. There are those who see the museum as an irredeemable reservoir of class ideology—the very notion of the museum is corrupt to them. Then there are those who are critical of the museum not because they want to blow it up but because they want to make it a more interesting and effective cultural institution.

You’d be in the latter category, of course, since you’re an avid collector yourself.

Yeah, I love museums. I think the design of museum exhibitions is an art form in and of itself, on par with novels, paintings, sculptures, and films. This doesn’t mean that I don’t acknowledge the ideological aspect of the museum as a site of ruling-class values pretending to be public. Nevertheless, as an institution dedicated to making things, ideas, and experiences available to people not based on ownership, I don’t think museums are inherently bad, anymore than books or films are bad. It is also clear that people enter the museum with their own agendas. Museum visitors are not mindless subjects of ideology. I think many of them have a healthy skepticism of institutional narratives.

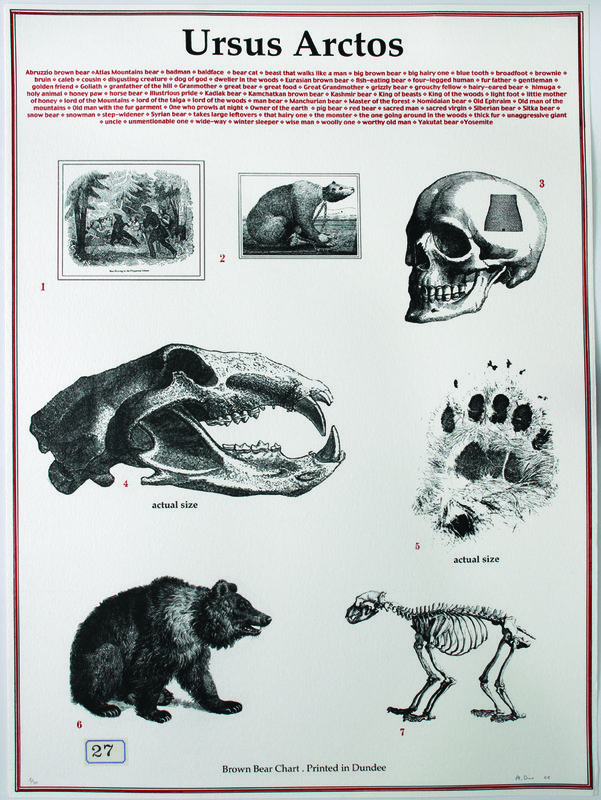

On Tropical Nature

(1991)

On Tropical Nature

(1991)

In 1990, when you interviewed Michael von Praet, one of the people responsible for the reorganization of the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, you commented: ‘I’m interested in the tension between the museum’s position as an educational forum, and an entertainment form.’ Can you describe how you explore that tension in your work?

As sites of learning and knowledge, museums have traditionally been places of extraordinary seriousness that shut out popular culture. But now there are very concrete pressures for museums to appeal to popular taste because of dire funding situations. For example, museums in England and United States, which once had the benefit of state money, got their funding cut during the Thatcher and Reagan years to the point where they had to cannibalize themselves in order to pull in the admission-paying masses. In many countries, museums are trying to find new ways to remain economically viable as businesses. The explosion of gift shops, restaurants, entertainment programs, and public outreach projects are testimony to the museum’s redirection towards becoming more popular.

But a disturbing thing about these shifts is that as the museum has become more ‘educational’ as part of its popularization efforts, it’s also become dumber. The museum seems to conceive of its audience as younger and more childlike now. Rather than a place where one might go to explore some complex questions, the museum now simplifies the questions and gives you reductive answers for them. It does all the work, so the viewer is always passive. A museum should provoke questions, not spoon-feed answers and experiences. Unfortunately, though, that seems to me what museums have become.

When it comes to museums, I’m an ultra-conservative. To me the museum embodies the ‘official story’ of a particular way of thinking at a particular time for a particular group of people. It is a time capsule. So I think once a museum is opened, it should remain unchanged as a window into the obsessions and prejudices of a period, like the Pitt Rivers in Oxford the Museum of Comparative Anatomy in Paris and the Teyler Museum in Harlem. If someone wants to update the museum, they should build a new one. An entire city of museums would be nice, each stuck in its own time.

But to get back to your question, I’m excited by the tension between entertainment and education in the ideas of the marvelous, especially in Pre-Enlightenment collections like curiosity cabinets and wunderkammers . Along with visual game, logic tricks, and optical recreations, these collections attempted to rationalize the irrational. They were neither dry didactics nor mindless spectacles. They tested reason the way storerooms, flea markets, and dusty old museums challenge cultural categories and generate questions today. This must sound light years away from when we spoke of documentary earlier, but somehow it’s related. If an exhibition is a challenge, it is both educational and entertaining.

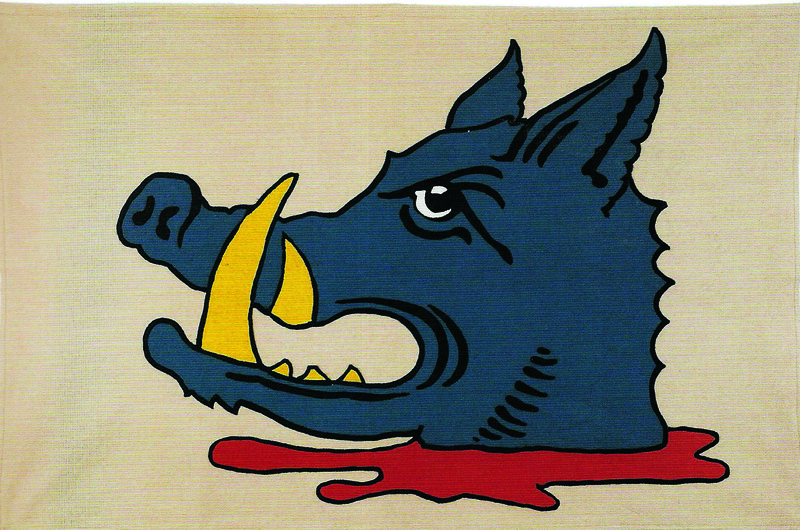

Tar and Feathers

(1996)

Tar and Feathers

(1996)

How do you provoke a sense of the marvelous or generate curiosity in our day and age?

One thing is to tell the truth, which is by far more astounding than any fiction (I cringe as the word ‘truth’ passes my lips, but I always mean it with a lower case ‘t’). For example, one of the biggest problems I have with the environmental movement and the museum is that they intentionally mislead people for the benefit of their own pocketbooks, which is unforgivable considering they are organizations devoted to the production of knowledge.

The problem of charismatic megafauna, for instance, which Bill Schefferine and I tried to deal with in The Survival of the Cutest (1990) is a case in point. Generally, in order to raise money for the protection of endangered ecosystems, conservation organizations draw isolated attention to extremely attractive and photogenic animals—tigers, whales, pandas. These are not keystone species so the system won’t collapse if they are taken out. Of course, all members of an ecosystem are important, but these animals are often the least critical ones, usually peripheral animals at the top of the food chain. They’re not like the beaver or corals which produce systems that support other animals. Now, foregrounding charismatic animals is not so bad if you acknowledge at some point their relationship to other forms of life in the ecosystem. If the conservation efforts could highlight the fact that by protecting the jaguar, we can also preserve vast areas of habitat that benefits everything in it, including us, then the focus on the ‘cutest’ would not be so problematic. But that’s not what the conservation groups do. They haven’t taken the opportunity to reveal the real goals. To me, that shows how much they are working against themselves.

Which parallels the art museum culture in so far as it continues to highlight the ‘charismatic’ masters to draw people in to the museum, to ‘save’ the institution, perhaps.

Right. In the case of natural history museums, what you see on display, which represents only 1-10% of the entire collection, is usually remedial pandering equivalent to the material in school science textbooks. But there are hundreds of people in the back rooms working with specimens and artifacts, hidden from public view. That’s where the museum is really alive and interesting. They directly address questions like: what is the function of a collection? Why is it important to name things in the natural world? The museum needs to be turned inside out—the back rooms put on exhibition and the displays put into storage.

Art museums act like butterfly collectors, always repressing content and process. We would understand Manet better, for example, if his paintings were exhibited alongside works from the academy he was reacting against, rather than the impressionist paintings from thirty years later. So I say freeze the museum’s front rooms as a time capsule and open up the laboratories and storerooms to reveal art and science as the dynamic processes that they are.