Growing up, Kerry James Marshall was troubled by a distinct lack of African-American representation in art and in the larger media landscape. Often encountering images of brutality and suffering, he sought to change the narrative by crafting works that acted as a celebration of black life and identity. From depicting children at a July 4 th barbecue, to two figures slow dancing in their living room, Marshall’s works proved to be tender, powerful, and a welcome addition to the Western canon.

His figures are always rendered in a deep, rich black, inspired by a disarming trend he noticed taking hold in the 1980s. “The only way [black artists] could stay with the black figure was by compromising it,” he remarked, “by either fragmenting it, or otherwise distorting it, by making it green, blue or yellow, or some other way to deflect the idea of its blackness.”

Marshall has continued in this fashion for decades, crafting monumental, mural-size paintings of powerful and jubilant black subjects in every-day settings. Coming off the heels of his first career survey, Marshall has elevated from important contemporary figure to undisputed master. In this excerpt from Phaidon’s brand new monograph, Kerry James Marshall , the artist sits down with conceptual artist Charles Gaines . The two discuss Marshall’s childhood in South Central Los Angeles, his approach to art-as-activism, and the inspiration behind his landmark work, Self Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980) .

***

Heirlooms and Accessories, 2002

Heirlooms and Accessories, 2002

Charles Gaines: When I was researching Dieter Roelstraete’s 2012 interview with you for this conversation, one work you discussed that stood out for me was Heirlooms and Accessories (2002), because it addresses the idea of art and activism. This is a photographic triptych of lockets containing close-up pictures of women who were present at a lynching in the Jim Crow South. Your discussion was about how certain figures might be interpreted. For example, images of white women suggest the stereotype of the black sexual predator, while the metaphor of hanging is provoked by the necklaces themselves. For me, this raises questions about your thoughts on art and activism. For example, what do you expect when you raise these kinds of issues in works of art?

Kerry James Marshall: Well, I guess the simplest way is to start with a question like, does one look at a work like that politically because of its relationship to history and politics? You can see how doing a thing like that can have an activist quality to it. But in terms of what that work is supposed to do, I never think of artworks as having a quality that’s intended to mobilize people to action. They don’t make people do things. But they do put questions in the mind of a viewer that they may not have entertained before. Everyone has in the back of his or her mind the idea that America was built by violence. But we never really think about how. The standard model is that white supremacy is only the guys in white sheets. You never really think about how completely embedded in the culture as a whole this notion of white supremacy is, and how everybody else’s relationship to it, the people who were in the sheets and the people who might never have put one on, but benefitted from the effects of this terror, helped to legitimize lynching as a part of the natural order.

That photograph, from which I isolated the women’s faces, is often reproduced. It’s a lynching that took place in the 1930s, in Marion, Indiana. It was a double lynching that was supposed to be a triple lynching. So when I did Heirlooms and Accessories , one of the things that I wanted to remind people of – and my art-as-activism is more like a reminder – is that there are angles and dimensions of history that are products of the relationships between the powerful and the powerless that people don’t quite consider. If you allow them to, people will always pretend not to know that these bygone events form our current reality. What was important to me about that photograph was not only the crowd of people who were there, but also its generational span, and that it wasn’t just men who perpetrated that violence but also women, who were often a causal factor. So I focus on three women who happened to be looking out at the camera. There’s one man in that photograph who’s looking out at the camera too. He’s the man who’s pointing at the bodies on the tree. He has a Hitler moustache. But if I’d focused on him, it would have been too obvious; it would have diverted attention from the ordinary folks who help perpetuate this type of violence. Those three women: a young girl who can’t be more than fifteen or sixteen, a girl who’s got to be about twenty or twenty-two, and an elderly woman who’s in her fifties or sixties, represent a generational span that was really important because it shows how structures of power are inherited; how power is transmitted generationally, from the men, through the women, to the culture.

The title Heirlooms and Accessories has multiple implications. An heirloom is a thing that’s handed down. Accessories are add-ons or adornments that enhance the spectacle, or yourself. Everyone who’s present at that event is an ‘accessory’ to the crime. The piece is constructed to be like a jewel box; that’s why the frame has a groove and there’s a strip of rhinestones that goes all the way around the frame. The idea is for the object to embody the concept of Heirlooms and Accessories on all of those levels. I wanted to combine the experiences of repulsion and attraction; you’re repelled and enticed at the same time.

One could compare this work to Adrian Piper’s 1989 work titled Free #2 , which includes an image of a lynching. Her interest seems to have been to use art to confront racism directly by aggressively challenging white people’s sense of identity, which is directly linked to the practice of lynching, a more psychological approach than yours.

I deliberately take a different approach, maybe in part because my experiences in the world have taught me that a direct confrontational approach does more to shut down examination of a subject or an issue than it does to compel a spectator to engage with it fully. Confrontation is nagging and irritating, so I’ve always felt that a certain oblique angle at a thing is more effective.

Certainly in terms of an individual work of art, it’s hard to establish proof of a cause-and-effect relationship that shows that art can affect social change. But maybe the hope is that collectively something can happen. For example, the memories of lynching that you bring up may not by itself result in social change, but as part of a collective of voices where others are also addressing these memories, maybe social change can happen.

That’s a part of the problem. For most of us, the images we encounter of things like lynching are sensational, but pretty remote. Most of us haven’t been eyewitnesses to any of those events. And so what we’re doing is constructing an idea of what these things are from other people’s stories and images. What’s produced collectively is inadequate for making anything more than generalizations. I grew up in South Central Los Angeles. We lived in Watts, but we moved out of the Nickerson Garden Projects there before the Watts riots took place. So when the riots broke out in 1965, we were living on 48th Street between McKinley and Avalon. We’d heard on the news that the thing that caused the riot was a traffic stop on Imperial Highway, in which the man who was stopped was riding with his mother and that the police had roughed up his mother. We heard that this police violence sparked the riot; the crowd that gathered around this incident became violent, which later turned out not to be true.

I get your point, in terms of what fuels events; there’s a difference between what we might individually know from actual experience and the idea of collective knowledge, which is a combination of direct experiences and collective assumptions that are often wrong.

We were on 48th Street and Imperial Highway. Where the riots started was 120th Street or something like that, maybe 125th, blocks away. So by the time the riots got to where we were, it was like a carnival. People were burning up the stores on Central Avenue and Avalon Boulevard. This happened during a period of discontent from 1965 up to 1969. During those years I went to Carver Junior High School and saw it get so embroiled in the Black Students Union issues that trickled down from Berkeley. Some of the issues were the same that you hear now, such as integrating black history into the American history curriculum. The violence that took place seemed confusing to me. The kids were burning up the school in protest. You had teenagers beating up the vice principal. There were rallies on the athletics field that got people excited about a lot of stuff that was supposed to be wrong but was the interpretation and translation of people who weren’t even going to school there. It was like what was happening with the riots. There were no proper black history classes then. One of the students’ demands was that they start offering these black history classes, but the first semester they offered Negro history, it was seriously under-enrolled. It was elective, not required. I signed up, but I thought, ‘What about all those people who were claiming that this was what we’ve got to have? Alright then, where is everybody?’ Those kinds of events, and discrepancies between what people know and what they don’t know, what people say they want and what they do, those things shaped my perception of discourse. How do you resolve these discrepancies? I started seeing that the responsibility for my needs shifted to me as opposed to a collective. I try never to approach a thing as if I’m one hundred percent certain about what it is or what the proper response to it is supposed to be.

This is an interesting issue for me. It’s clear that you recognize a complexity in the way political, social and cultural issues affect people’s lives. It’s also clear that an understanding of that complexity will make you better able to deal with these issues than any ideological framing could do. You may not agree with this example, but let’s take discrimination as a social/political issue: you address the issue as a subject, but you also address the complexity of how it plays out subjectively in society. It seems to me that you’re more interested in discrimination as a subjective experience because, as you said, you’re more interested in how you experience an issue, not in its ideological framing .

On a related matter, I wanted to find out how you came up with the idea to engage the political subject in your work, and so I researched how you became interested and involved in making art. I read how at one point you were introduced to the work of Charles White. I was wondering if he played a role in your discovery of what you wanted to do as an artist?

Well, it had something to do with it. It’s funny, I was going to say ‘indirectly’, but actually it’s a combination, directly and indirectly, because I first saw his work in a class I took at Otis with George de Groat. It was a drawing class for junior high school kids, and he showed us images from a book on White [ Images of Dignity: the Drawings of Charles White ]. I took the book and copied an image of Frederick Douglass. Looking through this book I noticed a couple of things about White’s work. One was that all the murals he did were about history and included historical subjects like Booker T. Washington, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth. They were also in individual pictures he did; there were several images of Harriet Tubman, a couple of Frederick Douglass, a few of John Brown, too. I was familiar with these figures because they showed up in history books. This is why, for me, White’s work was about history. I didn’t think of history as politics, really. White’s work accounted for the past in the same way that other historical moments are accounted for through art, such as Goya’s The 3rd of May and Picasso’s Guernica , as well as the historical paintings of David, Géricault and Delacroix. Not only that, but the entire legacy of classical Renaissance painting was for me based on reading the biblical or mythical subjects as historical. Growing up you understand how religion could be thought of as real, which made those stories history. Jesus narratives like the Stations of the Cross, the Virgin Birth, Rembrandt’s The Blinding of Samson came from the Bible. So it seemed like painting history was what artists did. My whole concept of what it meant to be an artist was formed around the idea that you picked subjects that were historical and meaningful so that people could derive meaning in their lives from the things they saw in paintings. That’s really how I began to understand what it meant to be an artist.

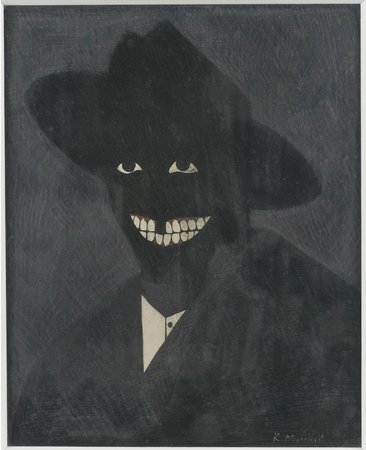

A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980

A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980

The reason I was thinking about that in relation to the political subject is that if you think about the kind of works in history that you just described, it’s reasonable to conclude that there’s a difference between the political and the historical, that you’re talking about a person or an event who’s importance to history has been established, not an ideology that’s still under scrutiny. But if you also think about the history of portrait painting and genre painting, the Barbizon School, Courbet, where the life and experience of ordinary people became the subjects, the difference between history and politics is less clear because it’s not just about the historical moment, but also the present moment. In relation to modern painting, classical too, but particularly modern, reflecting on figures like Douglass is seen most often politically because what they’ve done in the world is still part of a continuing conversation. The issues haven’t been settled by history. So within this framework, works of art may reflect on issues or causes that still have social significance. I’m suggesting that a historical genre such as the portrait can become political when the subject is black because the idea of the black subject is still unresolved.

I never thought of it that way. Also, we’re talking about when I’m thirteen, fourteen, fifteen years old, when I’m just forming my idea of what it means to be an artist. I don’t know what grade it was, probably third or fourth, when they took you to the school library – that is, when every elementary school had a library. And then they would take you on a field trip to the public library. Before then, you have no concept of anything, not of history, politics, sociology or race or anything. That stuff is all out there, but you don’t have a framework to fit it into that makes it comprehensible to you.

So your entry into the political was through history. When did it occur to you, the idea of the black subject?

That didn’t occur to me until I found out about White, because I simply accepted the majority of images I saw in books as representative of humanity, as the norm.

At a certain point, as you developed, as you worked through the idea that painting history was what artists did, you recognized the absence of the black subject in the history of painting. And at that point you understood it as a certain political space.

That really didn’t take shape with any kind of clarity until 1980, when I made the pivotal painting A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self . This was when it started to look like there was something that could be done with the black figure, that it could be used to explore ideas that are not only relevant to picture making by itself but also to convey some of these ideas that I’d been developing about where black people fit in. Before then, apart from self-portraits, which I’d do as an exercise, I was doing still-lifes and paintings of inanimate objects in order to figure out how to paint. I copied White’s work because I’d read in books how artists became artists: that they copied the work of a master and learned to make pictures that way. I used White for that reason. The images were appealing to me, but I didn’t see them as oriented towards a politics of race.

So the issue of representation was something that evolved more slowly.

It really came into focus with that one painting.

I just saw the Degas show at MoMA. There was an interesting comment by Degas in which he talked about copying artwork. He described a series of exercises where he did a drawing and copied it. And then he did a drawing of the copy and copied that. I found this comment to be one of the earliest examples of linking technique with style, where the analysis of style is a critical assessment of technique. Therefore copying for you revealed White’s thoughts, leading to representation, as well as his skills.

This is one of great functions of that book. You can see an evolutionary transformation in the way he was making an image in the beginning and the way he was making it towards the end. You understood clearly that things don’t have to remain the same. At the same time there’s a consistency, which I understood as a product of conscious decisions about style, about regulating change. The other thing that was important was a 1971 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the first exhibition they did of White’s work. There were three black visual artists in that exhibition: Charles White, David Hammons and Timothy Washington. I went to see that show dozens of times. They were so radically different from each other but equally powerful. That was an important moment for me, too.

This brings me to a more in-depth question about your attitudes towards the formal properties of painting and their relationship to content. In a published interview, you and Dieter Roelstraete talked about the in influence of Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man on your work. This seems to be a key moment in your effort to represent blackness in painting. You talked about how race, particularly blackness, was negotiated through Ellison’s representation of absence, that you could represent absence through colour. I wonder if you could go more into this idea of absence in relation to the formal properties of painting. To me, you’re a master colourist; there is no other painter in the history of painting with a greater mastery and understanding of colour. It’s not only your colour sense, but also your understanding of its metaphorical and discursive potential. My question is really about the colour black, both as a representation and as an aesthetic property. How in your mind does a colour like black lead to a critical space like race, particularly through the metaphor of absence, without compromising the materialism that preserves colour as a sensible experience?

It’s the result of the confluence of a lot of different things and ideas. Ellison’s book was a trigger for some of these ideas and a catalyst for finding ways to synthesize them. And White was also the gift that kept on giving. It was important that White was at Otis. Through him, I was introduced to many people, and things. I made the decision that when I got out of high school I was going to go to school there. Before then, I wasn’t on a track to go to college. White’s presence at Otis changed that. His class met in the evenings, so I couldn’t take it then; there wasn’t anybody that could take me. So I signed up for a Saturday painting class with a man named Sam Clayberger; he was a painter of nudes basically. My approach to colour derives almost exclusively from the way Clayberger thought about and used colour. I didn’t know until about a year ago that he was an animator who had worked for Hanna-Barbera. This made sense; there was something about his colour sense that seemed right for cartoons. He was the first person I heard talk about the way you use colour instrumentally. His approach looked arbitrary, but it wasn’t. He said you could substitute any kind of colour to function as a shadow so long as it had a relationship to the other colours that were near it. And so I learned to start building shadows using purple, green and blue from him. He also introduced me to the fact that none of these things are coincidental; that you decide on them and it’s all because you understand something about the structure of the way a picture works. He was also the first person who taught me you can analyze the way paintings work, that you can break them down and see how things fit together. Sam was different from Charles White, who was the master of drawing. White would show me how to set up and construct the face the way he did it. They would both talk all the time about history and politics; this is why I thought those things were important. I could see how White’s interest in the politics of the image was reflected in everything he was interested in. For example, he would bring in Goya, The Disasters of War and Los Caprichos , He used to bring in a book of the complete works of Käthe Kollwitz, his favourite artist. When I finally got to Otis in 1977, I met another painter, Arnold Mesches. Charles had the image and its relationship to subjectivity, Sam had the colour, and Arnold Mesches had the structure. These are the people who unlocked for me the way to understand paintings.

Because of these influences, you came to understand that the political subject was imbedded in the idea of painting mastery. As part of that mastery, the idea of the black subject seemed wholly consonant with the idea of making a good painting.

In the late 1960s, early 1970s, maybe it happened a little earlier, there seemed to be all these conversations about participation in the mainstream and how to go about achieving it. For a lot of artists, it seemed that the only way to do this was to abandon the black figure. Not only was abstraction supposed to be more advanced, but also you were never going to achieve any great recognition until you let go of the black figure. And some people thought that the reason White never got the kind of recognition that people thought he deserved was primarily because he was too close to those black figures. There was a period in which I abandoned the black figure too, because I wanted to spend more time figuring out what pictures looked like, and how surface, colour texture, and all those things operated. I was doing a lot of collage work and mixed-media stuff. The Ellison book became the trigger that sent me back to the figure. I understood on some level that the abandonment of the black figure was a kind of loss and that I’d surrendered to a power structure rather than trying to challenge and overcome it in some way. And so A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self became an instrument to solve what I thought might be some deficiencies in some of the work that White was doing, as well as the work that some other black painters were doing in their use of the figure; I used the power of abstraction to solve these deficiencies in the way the figure was represented. I wanted to use all of the colour complexity that I’d learned from Clayberger, but to keep it close to black history, culture and the subjectivity of White’s work. So A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self was a way of starting at a zero degree because it was at, it was schematic, but it was built on all of the stuff I’d learned about picture making from my teachers at Otis that was opposite to the way a number of black artists approached the picture; the only way they could stay with the black figure was by compromising it, by either fragmenting it, or otherwise distorting it, by making it green, blue or yellow, or some other way to deflect the idea of its blackness.

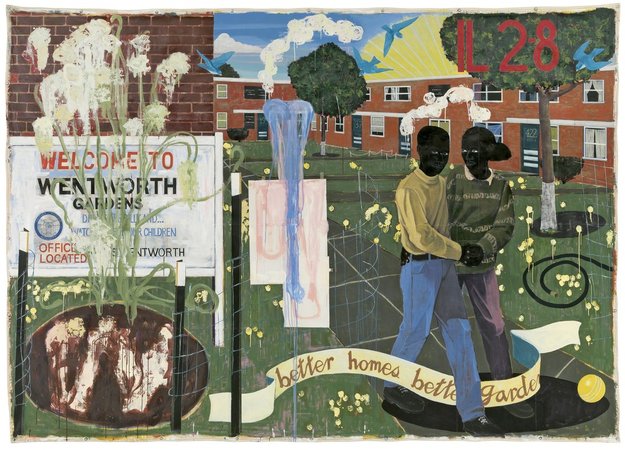

Better Homes, Better Gardens, 1994

Better Homes, Better Gardens, 1994

This is a jewel, what you’ve just articulated about the issue of colour, abstraction and content. I’m reminded of a panel discussion in the 1960s sponsored, I believe by Artscanada, titled ‘Black’. Two of the participants were Ad Reinhardt and Cecil Taylor.

You were there?

No, I wish! But there’s an essay available that recounts the event. I heard about it from my friend the late Terry Adkins. We were trying to think about how to reconstitute this panel and restage the event. The panel was about blackness and the colour black; the purpose was to explore the political and aesthetic meaning of the word in order to question the saliency of political ideas in 1960s modernism. Anyway, Cecil Taylor and Ad Reinhardt got into this big argument. As I said, the subject was simply ‘black’ – it didn’t tell you black what. For Reinhardt of course, the word ‘black’ referenced a universal idea because black and absence were for him trans-lingual. ‘Black’ expressed a kind of universalized experience operating outside the domain of language. For Taylor, black was steeped in language; it couldn’t be considered except as a metaphor because of his experience of dealing with it politically. One idea that came out of this debate was that the term provoked a binary that ultimately placed constraints on our thinking: how the meaning of the term is informed by one’s experience. Even though Ad was making the argument that it was trans-linguistic, only a white person could entertain such a pure notion. The suggestion was that its racial connotation is irrelevant to ideas of art. Cecil found in Ad’s commentary the kind of ideological thinking that perpetuates racism. And so your project seems to be an interesting attempt to describe how the trans-linguistic aesthetic properties of painting and the linguistic properties of content merge and come together, to debunk the binary.

When I made that picture, I think I understood for the first time that the image in it functioned linguistically. Which is why I always said that the idea of blackness operated rhetorically. This materially black figure has to be situated within the larger context as a linguistic figure amongst other linguistic figures, or as a pictorial figure within the context of other pictorial elements. Take, for example, the essay Carter Ratcliff wrote for Art in America some time in the 1980s, ‘The Short Life of the Sincere Stroke’. He talks about the way that every mark in a picture is a linguistic character in the sense that we deploy these marks to construct certain meanings and relationships. One of the reasons why the figure works so effectively for me is because I’m thinking of it in those terms, as an abstract linguistic figure and at the same time as an absolute sign or symbol of something. That’s why I’m able to continue working with the figure in ways that others haven’t. I understood that language structure continuously modifies meaning; it never disappears. It simply finds other contexts in which the figure can be used. But recognizing language’s role in those terms imposes a certain amount of responsibility. Whenever communication is an issue, a certain kind of clarity is important, so you have to be responsible for the way you use language. That’s why it takes me so long to make my pictures. When I insert a figure into a painting space, I have to consider all of the things that it means and then construct, edit and revise in order to reach its maximum effect so that blackness becomes a noun, not an adjective.

Well put.