Opening May 26 at the International Center of Photography Museum, Magnum Manifesto celebrates the 70th anniversary of the influential photography collective founded in 1947 by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger, and David "Chim" Seymour. Beginning with Capa's Death in the Making, a book of photographs made during the Spanish Civil War, Magnum photographers have been drawn to areas of conflict. And yet, early on their work earned the appreciation of many artists, collapsing the boundary between documentary and aesthetic practice. Henri Matisse designed the cover of Cartier-Bresson's The Decisive Moment, who also studied as a painter.

Like most artist collectives, the photographers of Magnum Photos share a general style, but the 70-year history of the group has allowed it to adapt with the times. Thomas Dworzak's #auschwitz, a 2014 book of photographs curated from Instagram posts tagged with the name of the concentration camp, for example, is quite different from W. Eugene Smith's Minimata, a 1975 documentation of pollution and nuclear radiation in postwar Japan, despite both works dealing with the legacy of World War II.

RELATED: The Incredible True History of Magnum Photos

Many Magnum photographers have worked directly in the art world, as evidenced by Seymour's portraits of Peggy Guggenheim and Pablo Picasso, and Thomas Hoepker's portraits of painters like Andy Warhol and Willem de Kooning. Now, with ICP's exhibition, it's worth looking back at the many times Magnum photographers found themselves not only at the center of important events, like the Vietnam War and Civil Rights, but also the nexus of art, photography, and life. Excerpted from Phaidon's Magnum Photobook: The Catalogue Raisonné, with text by Fred Ritchin and Carole Naggar, here are just seven of the many influential photobooks published by Magnum photographers.

...

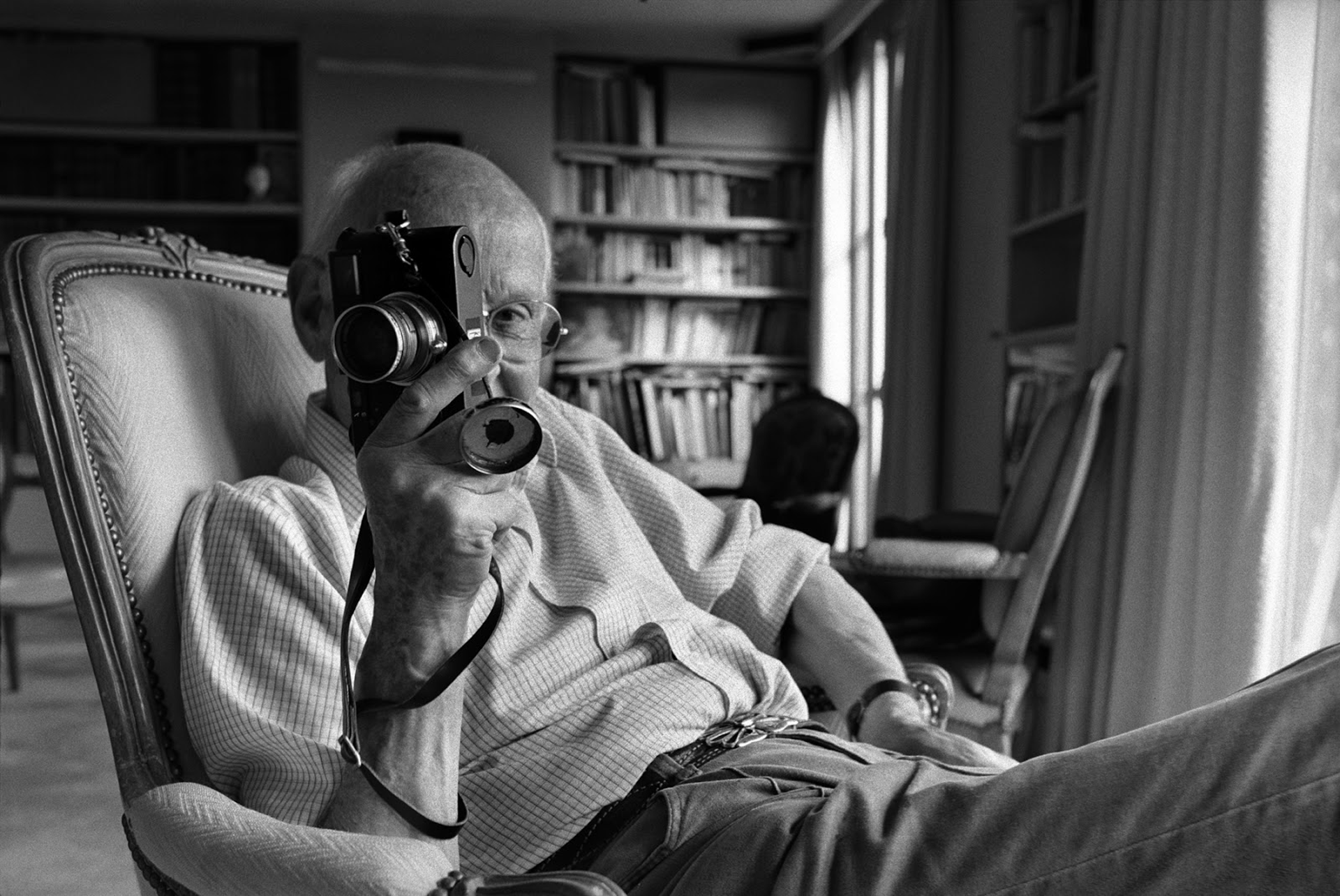

Henri Cartier-Bresson

The Decisive Moment, 1952

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson

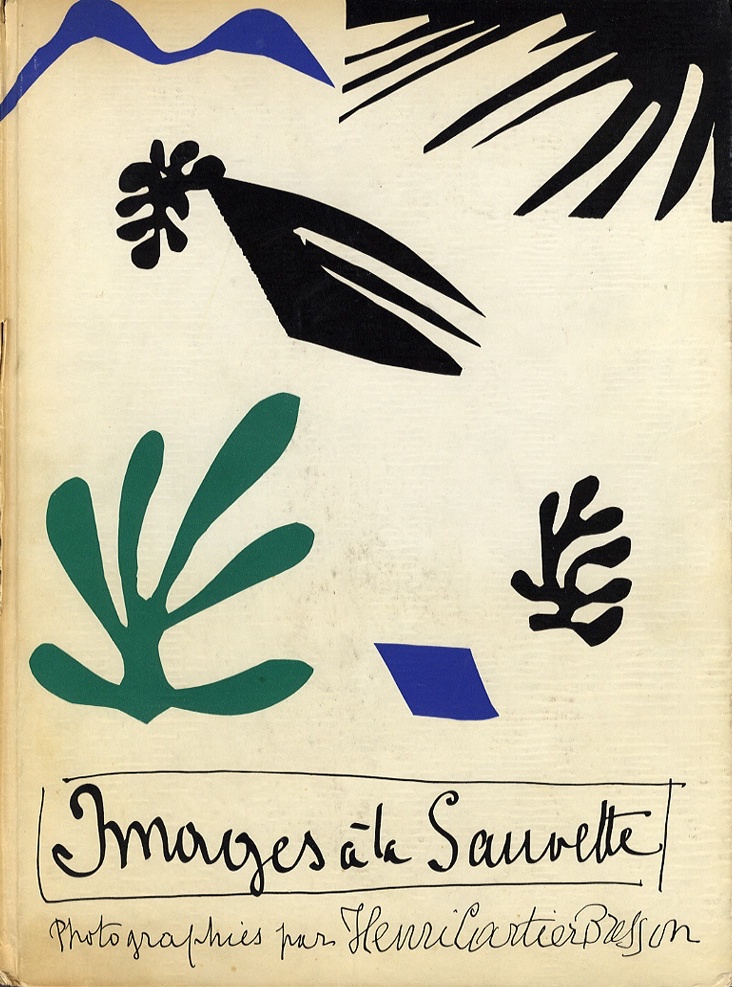

The Decisive Moment, published on October 15, 1952 in the United States and simultaneously in France as Images à la Sauvette (which translates roughly as "Images on the Sly"), may have been the most important photographic book of the last century. Its elegantly simple large-format design and the rich tones produced by the heliogravure printing that showcased the pointed, exquisite formal quality of so many of the French photographer henri Cartier-Bresson's 126 35mm photographs, made the book an emphatic statement of complex, independent seeing by a pioneer of photographic language.

The cover, designed by Henri Matisse, reflects the photographer's early early affinity for painting. The imagery within straddles the line between artist and photo-journalist, a synergy that he engaged for much of his career. And a well-formulated text reveals, among other insights, Cartier-Bresson's oft-quoted theory of the decisive moment: "To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression."

The Decisive Moment was Magnum co-founder Cartier-Bresson's first book and, according to a letter he addressed to his colleague, Marc Riboud, it was the publishing medium that he had come to prefer: "Magazines end up wrapping French fries or being thrown in the bin," he wrote, "while books remain." Conceived and composed by the Parisian publisher Tériade with the collaboration of Marguerite Lang, The Decisive Moment allows each image to nearly touch the edge of the page, and includes a caption booklet to as not to interrupt the visual flow. The book primarily displays two vertical images on facing pages, or two-page spreads with one large horizontal image (these are usually placed in the middle of the signatures to ensure the least disruption at the spine), along with a number of double-pages of three images and only two spreads with four photographs displayed.

The Decisive Moment is a modest, even ambivalent book. As the photographer cautions the reader: "These photographs taken at random by a wandering camera do not in any way attempt to give a general picture of any of the countries in which that camera has been at large."

Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment, 1952; cover by Henri Matisse

Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment, 1952; cover by Henri Matisse

Danny Lyon

Conversations with the Dead, 1971

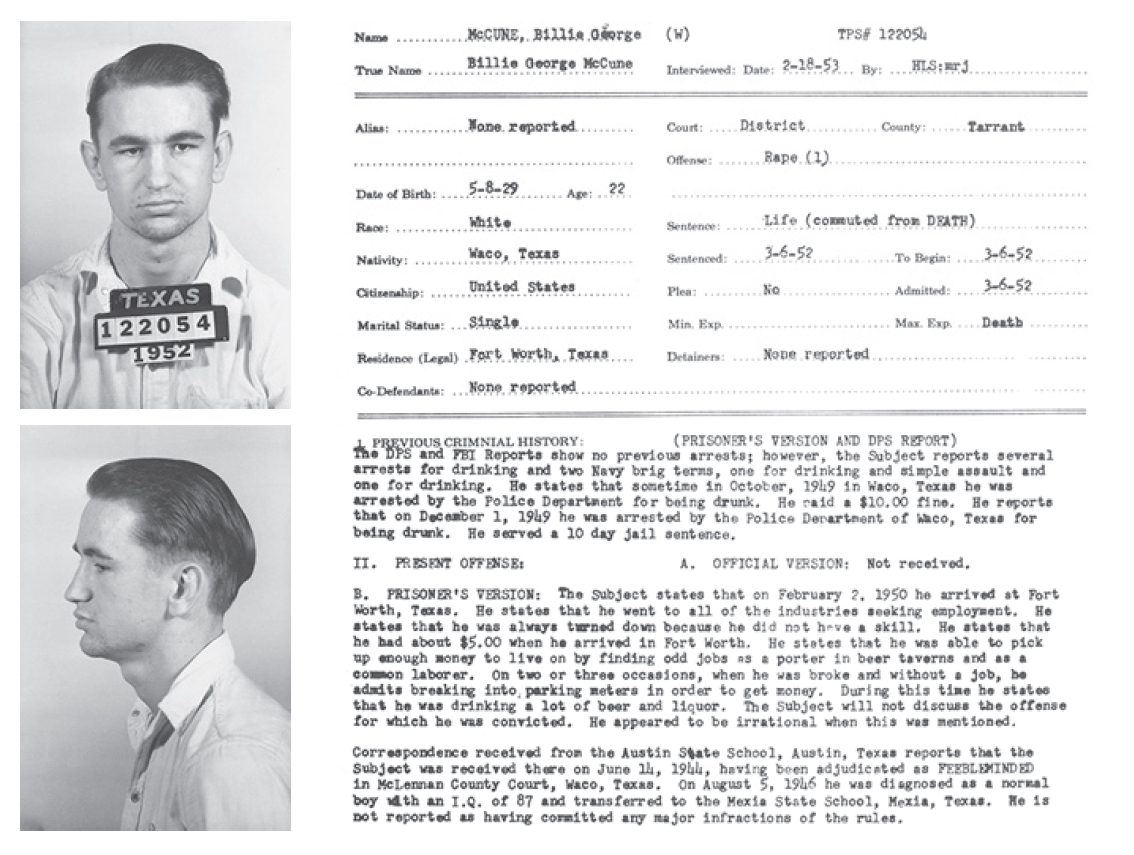

Billy McCune's rap sheet from Danny Lyon's Conversations with the Dead, 1971

Billy McCune's rap sheet from Danny Lyon's Conversations with the Dead, 1971

In 1967, Danny Lyon was invited by Dr. George Beto of the Texas Department of Corrections to photograph inside the state's prisons. Lyon spent fourteen months inside six Texas penitentiaries, where he was given access to enter at any time, unprecedented for a photographer. The result was Conversations with the Dead, a book where Lyon was no objective witness but an active participant in the style of New Journalism: with no pretension to objectivity, he became immersed in the life of his subjects. This has been the case with all of his books, such as The Bikeriders (1968) when he became a member of the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club, traveling with them and sharing their lifestyle in the Midwest from 1963 to 1967.

RELATED: Magnum Photographer Stuart Franklin's Artspace Picks

Besides photographing every aspect of the inmates' lives, Lyon recorded their personal testimonies, which are also featured in the book, among which the drawings and texts of inmate Billy McCune are prominent. Lyon's meetings with Billy unleashed "a torrent of writing and drawing," and as a result Conversations with the Dead is probably the first photobook where writing and drawing play an equal role to pictures: one of McCune's drawings features on the cover beneath one of Lyon's photographs. Lyon writes: "I did not believe that I could convey the reality of the prisons through my own writings alone. I wanted to drag the reader in with me. I also wanted the text to be beautiful to look at ... so I made my text from mug shots, reports, telegrams, and letters." Originally, Lyon wanted to produce the book inside the prison. Instead, he made a portfolio, "Born to Lose," in the print shop of The Walls, a penitentiary in Hunstville—the printing was supervised by James Renton, an inmate who learned lithography and offset printing.

Groundbreaking at the time, Conversations with the Dead remains relevant to this day. In Texas, Lyon photographed a world of 12,5000 men and women. Within a generation, that world has increased to 200,000—the second highest rate in the world, with about 22 percent of the world's prisoners.

Danny Lyon's The Line, Ferguson Prison, Texas, 1980 is available on Artspace

Danny Lyon's The Line, Ferguson Prison, Texas, 1980 is available on Artspace

Abigail Heyman

Growing Up Female, 1974

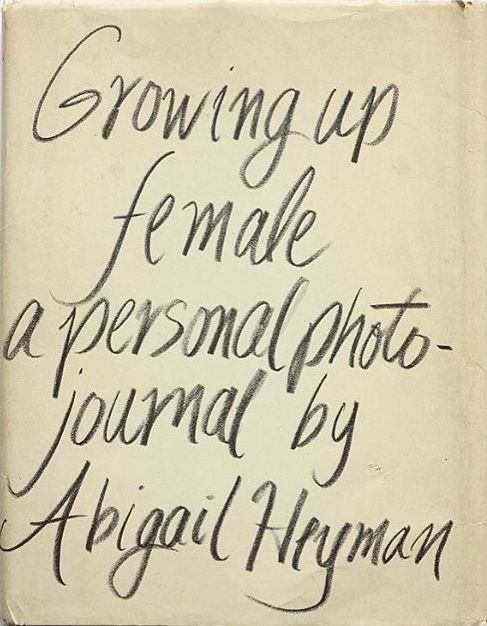

Abigail Heyman, Growing Up Female, 1974

Abigail Heyman, Growing Up Female, 1974

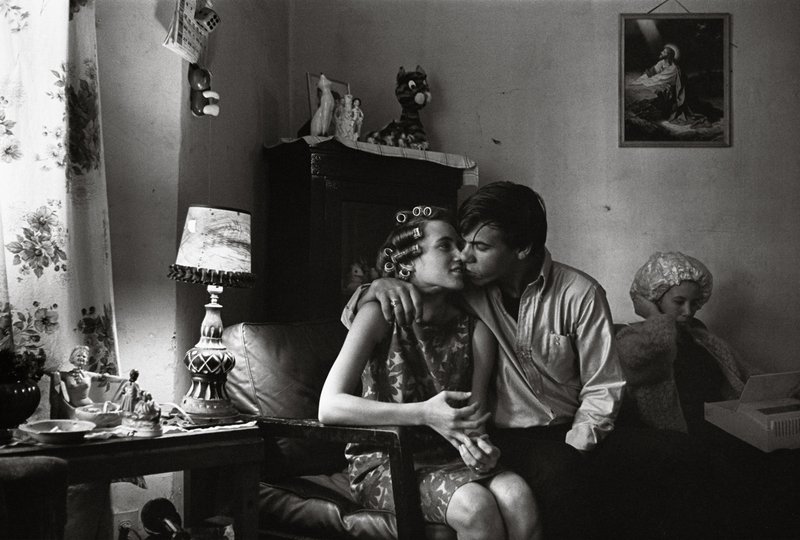

While Magnum Photos has had very few female members throughout its seventy-year history, Growing Up Female: A Personal Photojournal is a direct and articulate exploration by Abigail Heyman of a feminist's own nuanced struggle in defining herself. Published in 1974, during Heyman's years with Magnum (she left the agency in 1981 to form Archive Pictures with a number of other photographers, including Charles Harbutt and Mary Ellen Mark), the book emerged from an era in which the roles of women and girls were beginning to evolve in the United States. Rather than looking at a movement, Growing Up Female explores it, and the photographer's life, from within.

Reproducing actual handwriting, the text—excerpts from Heyman's own journals—emanates from her own intense attempts are consciousness-raising as a woman, but also reflects the experience of all women. The uncaptioned black-and-white photographs, one or two on each spread, range from an image of a woman spreading her legs in a strip joint to another of a woman in childbirth and one of a young woman surrounded by others while acting as the subject in a gynecological self-help grow. There is also an apparently first-person photograph of an abortion, the doctor looming above, with a text stating, "Nothing ever made me feel like more of a sex object than going through an abortion alone."

RELATED: From C-Print to Silver Gelatin: The Ultimate Guide to Photo Prints

A photograph of a cheerleader is across from another of a woman in jeans and a well-worn T-shirt holding a football, and there is another of a mother sitting on the carpet comforting her three children while her husband, seated at a dining table in the background, eats a slice of a melon. There is also an image of a young woman facing the camera in front of shelves of documents with text on the facing page stating, "I no longer feel flattered when men tell me I don't think like a woman." Ad a double-page flash photograph depicts young people at a dance holding onto each other in various forms of a clinch, somewhat unsure as to how to proceed.

"This book is about women, and their lives as women, from one feminist's point of view," Heyman writes to introduce the book. She also asserts, "This book is about myself. I looked at people and events long before I owned a camera, more as a silent observer than a participant, sensing this was a woman's place. It is no longer my place as a woman, but it remains my style as a photographer." Growing Up Female, which Heyman worked on "for the past thirty-one years" (she was born in 1942), ends optimistically: "I value women. I value myself. I don't reject being female anymore. I can become the woman I want to be, and I can help to develop a new society that will value her."

Abigail Heyman, Untitled, 1971

Abigail Heyman, Untitled, 1971

Eve Arnold

The Unretouched Woman, 1976

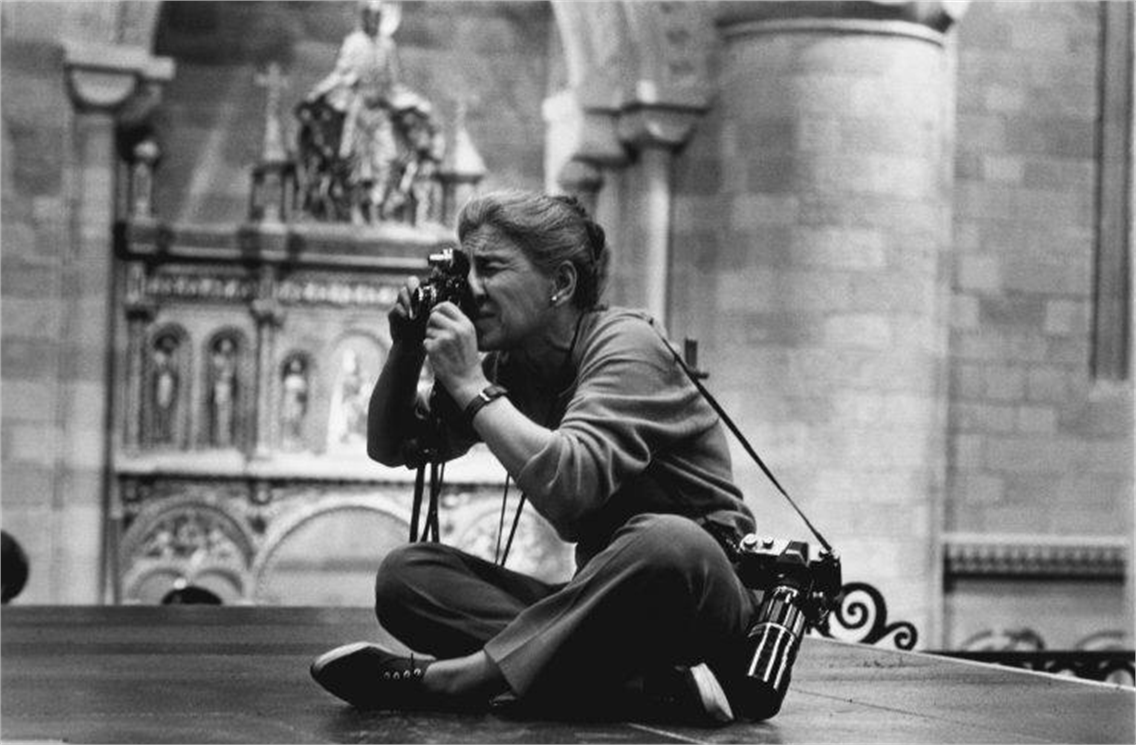

Eve Arnold

Eve Arnold

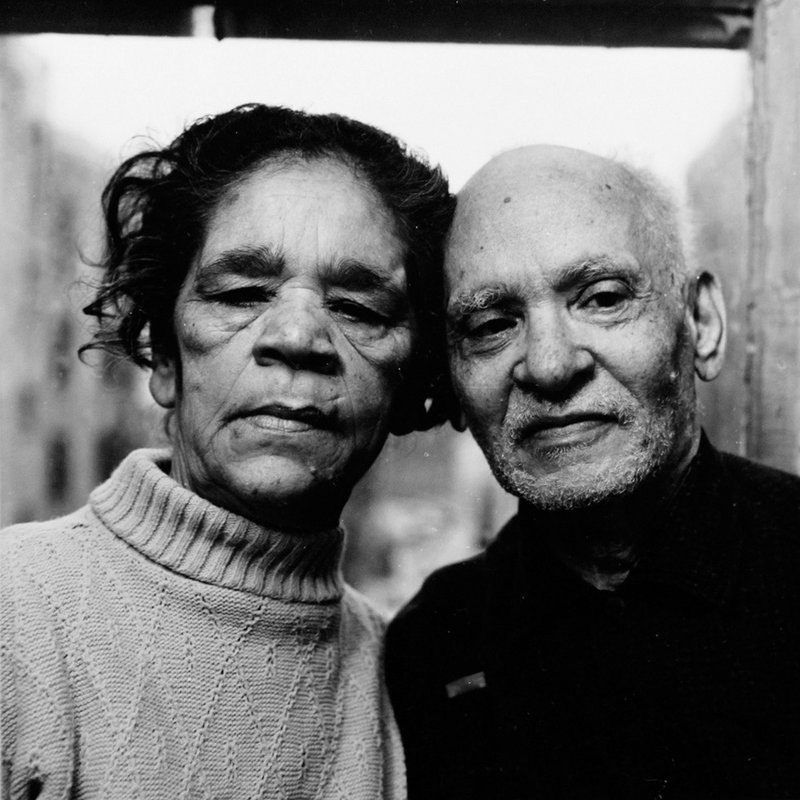

New York-born Eve Arnold was already in her sixties when she decided to publish her first book, and she was clear about its subject: "This is a book about how it feels to be a woman, seen through the eyes and the camera of one woman—images unretouched, for the most part posed, and unembellished." The Unretouched Woman took shape over several trips to New York, London, and Mexico. Arnold set up a darkroom and started printing images from a career that spanned twenty-five years of photographing women.

The book features Arnold's first reportage, about a behind-the-scenes fashion show of black women in Harlem in 1950, a story that led to her association with Magnum in 1951. (She became a full member in 1957, one of the first women, along with Inge Morath, to join the cooperative.) Equally at ease photographing potato pickers in Long Island and the Queen of England, Arnold selected subjects ranging from a nomad bride in the Hindu Kush to Zulu women in a South African hospital, harems in Abu Dhabi, barmaids in Cuba, a fencing mistress in a British school, African American women marking for civil rights in Virginia, and her famous portraits of Marilyn Monroe. The book's cover depicts four neat piles of color slides arranged in front of a lightbox on which further slides are illuminated, while a simple interior layout features Arnold's texts (written on a veranda in Cuernavaca, Mexico) alternating with a mix of black-and-white and color images, which together build a circuitous narrative through diverse countries and social classes.

RELATED: The Female Gaze: 10 Women Who Changed Fashion Photography As We Know It

Arnold worked with her publisher, Bob Gottlieb, editor-in-chief at Alfred A. Knopf, on the picture editing and monitored the printing of the final selection. The Unretouched Woman was published in the United States in late 1976 and a few months later in Great Britain to considerable attention, including interviews, reviews, a twenty-five minute film for the BBC, and excerpts in Sunday Times Magazine. While she edited the material for The Unretouched Woman, Arnold had realized that she could mine her material for more books, and over the next few years she published Flashback! The 50s (1978) and In Britain (1991). Bob Gottlieb would go on to publish six of Eve Arnold's books and become one of her closest friends; books became an essential part of Arnold's creative life, giving her a way to reflect and assess her work.

Eve Arnold's The Misfits... Nevada (1960) is available on Artspace for $279

Eve Arnold's The Misfits... Nevada (1960) is available on Artspace for $279

Sebastião Salgado

Other Americas, 1986

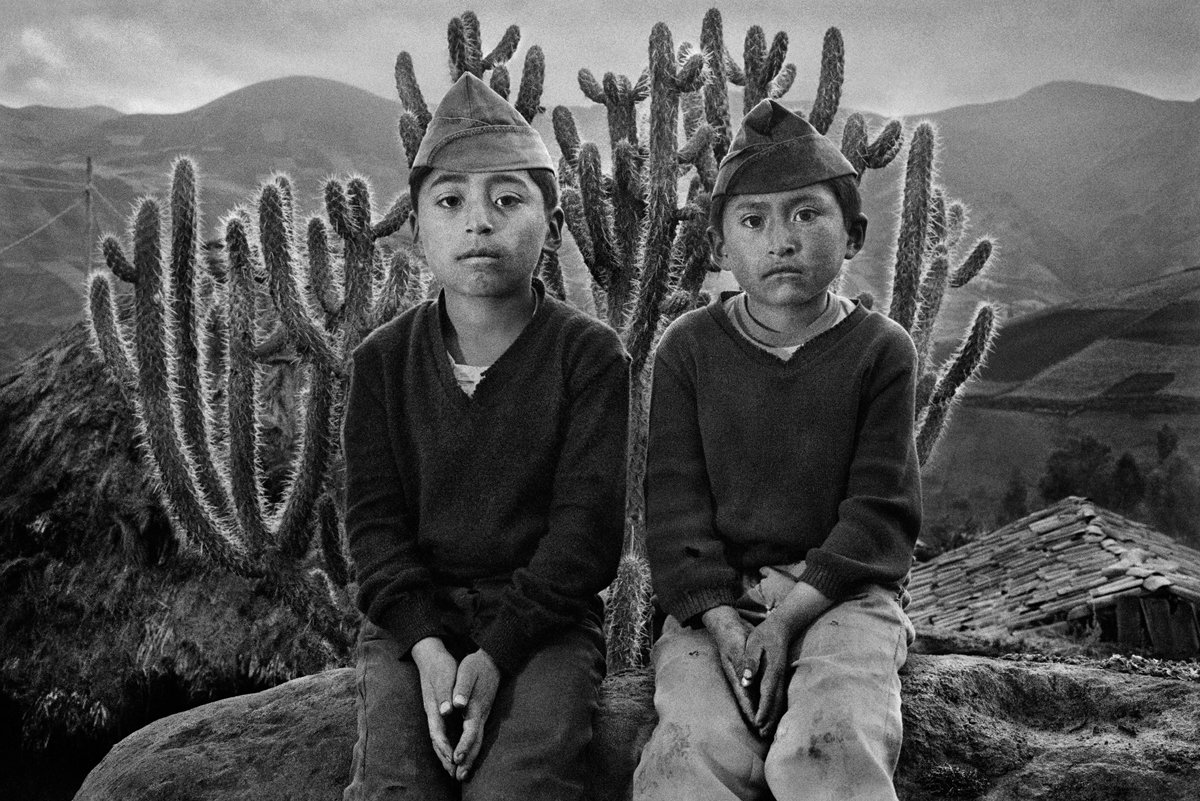

Sebastião Salgado, Ecuador, 1982

Sebastião Salgado, Ecuador, 1982

"The seven years spent making these images," Sebastião Salgado asserts in the preface to Other Americas, his first book, "were like a trip seven centuries back in time to observe, unrolling before me, at a slow, utterly sluggish pace—which marks the passage of time in this region—all the flow of different cultures, so similar in their beliefs, losses, and sufferings."

Salgado had relocated to Europe after fleeing the military dictatorship in his native Brazil, with his wife Lélia. Other Americas is an exploration of the cultures he had left behind, an attempt not to deal with the anguish and despair of those swarming into cities and their proliferating slums, but to articulate the strength of those who remained within the parameters into which they had been born. The book's title is meant to indicate the double otherness of Latin America and its rural people—first, because the USA has appropriated "America" for itself, and second because those in the countryside are considered "other" even in their own countries, where they endure far outside the circles of power.

Reflecting its meditative stance, the book is laid out with almost every photograph across two pages, captioned only with the name of the country and the year it was made. The people depicted in the black-and-white pictures inhabit a weighty quietude that greatly differs from the noisy materialism of the North—the photographer turns the tables, able to show those in the United States and Europe, his primary audience, how the everyday spiritual wealth of the South may outweigh their material riches. (The book was initially published in English, French, and Spanish, with three remarkably different cover photographs.)

In Latin America, "Every mountain was an adventure." Salgado walked for days to get to one village, was only the second outsider ever to arrive in another and in a third was considered a god. In one locale he unintentionally changed the way its denizens thought about a nearby river. When he explained that it eventually flowed into the Amazon and then into the Atlantic Ocean, they began to feel sorry for it and the long way it had to go.

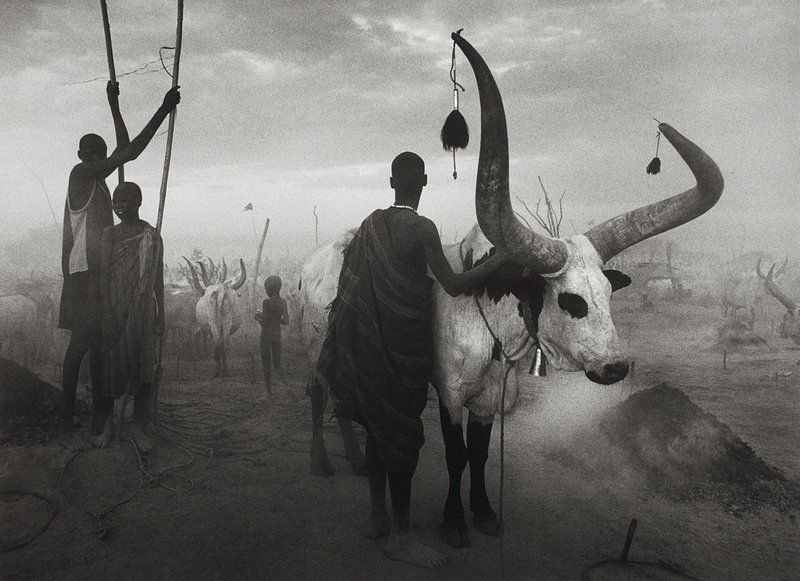

Sebastião Salgado's Dinka Group at Pagarau, South Sudan (2006) is available on Artspace

Sebastião Salgado's Dinka Group at Pagarau, South Sudan (2006) is available on Artspace

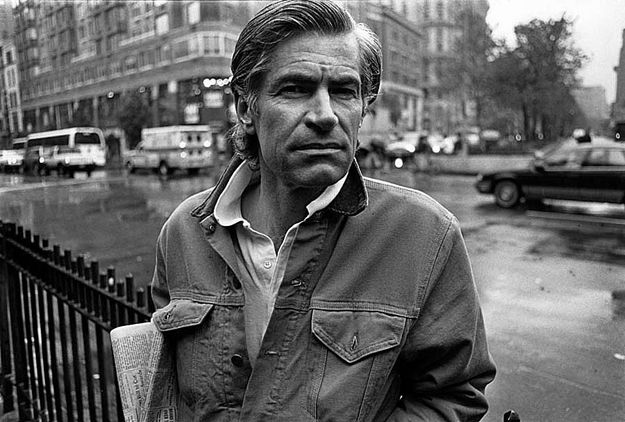

James Nachtwey

Inferno, 1999

James Nachtwey

James Nachtwey

James Nachtwey, who began working for Time magazine as a contract photographer in 1984, describes Inferno as both a compilation and extension of his work for the press. It is a chronicle of "a personal journey through the dark reaches of the last decade of the twentieth century," as well as his "attempt to go beyond the so-called 'best pictures' and to replace it with a sense of the flow of events: ongoing, real, existing beyond the presence of a photographer."

The severe, graphic, disturbingly resonant black-and-white photographs in this enormous volume chronicle a descent into various levels of hell. The regions Nachtwey photographed are listed on the contents page, every name centered one below the other: Romania, Somalia, India, Sudan, Bosnia, Rwanda, Zaire, Chechnya, Kosovo. An excerpt from Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy: Inferno is cited as the book begins: "There sighs, lamentations and loud wailings resounded through the starless air, so that from the beginning it made me weep."

RELATED: Investigating the Death of Photography at the ICP Triennial

There is little redemption here, divine or otherwise. Photographs of terrified, crazed, severely abused Romanian orphans begin the book in a sequence of dire misery. Images of dead bodies being picked up by bulldozers in Rwanda are included, as are photographs of agonizingly skeletal people dying during a famine in Sudan and others in Somalia. There are depictions of devastated ruins in Kosovo, and of a small portion of India's two hundred million Dalits, or "untouchables," who have been forced into the most menial jobs. One can randomly leaf through the book's 480 pages and expect to be frequently shocked, horrified, and rendered almost mute with despair.

But Nachtwey has another goal: "My job is to help reach a broad base of people who translate their feelings into an articulate stance, then through the mechanisms of political and humanitarian organizations bring pressure to bear on the process of change." As Luc Sante says in the introduction, Nachtwey no longer considers himself a war photographer but an anti-war photographer. And, all the evidence to the contrary that he so ably shows, Nachtwey continues to believe in humanity: "I have witnessed people who have had everything taken from them—their homes, their families, their arms and legs, their sanity. And yet," he writes in the book's last sentence, "each one still possessed dignity, the irreducible element of being human."

James Nachtwey, Afghanistan, 1996

James Nachtwey, Afghanistan, 1996

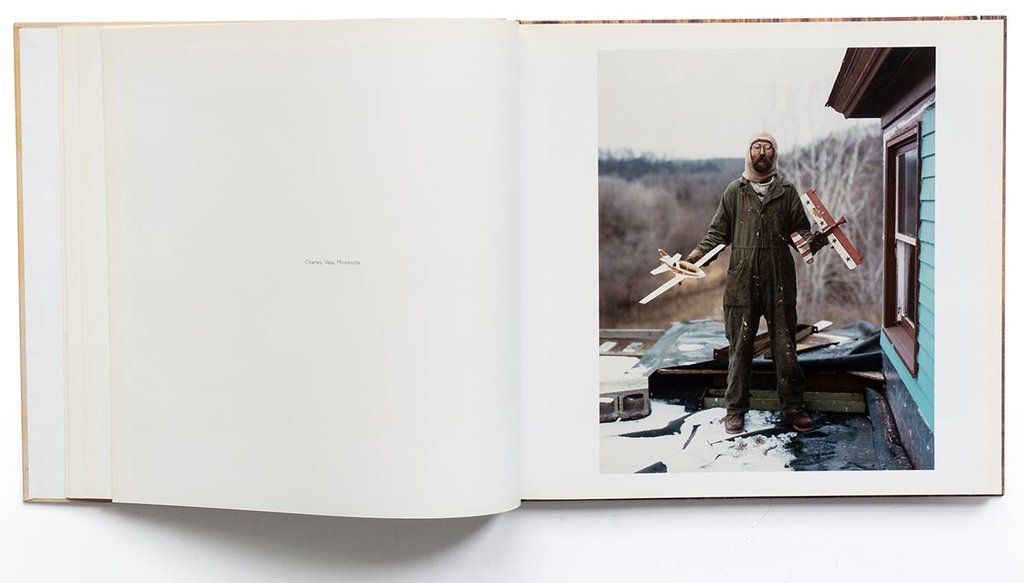

Alec Soth

Sleeping by the Mississippi, 2004

Alec Soth, Sleeping by the Mississippi, 2004

Alec Soth, Sleeping by the Mississippi, 2004

The work of Minneapolis-based Alec Both—a nominee of Magnum Photos since 2004 and a full member since 2008—is rooted in the American tradition of "on-the-road photography" developed by Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Stephen Shore. Soth made his first river-road adventure from Minneapolis to Memphis when he was still in college, and the magic of that trip remained with him.

Sleeping by the Mississippi documents a series of road trips made over four years during which Both followed the Mississippi Rivers from north to south, cold weather to warm, restrained to open. In Soth's first book, the idea was that one image would lead to the next, as if in a dream's free association (Soth says that the making of the book was itself the fulfillment of a dream). The Mississippi, whether present or not in the pictures, functions as a sort of metaphor. The book alternates portraits, often of marginalized or dispossessed subjects, with landscapes and views of interiors made with a large format, 8 x 10 camera, as Both meanders from church to marina, hospital to diners and brothers, cemetery to marshes, talking to his subjects and sometimes asking them to write down their dreams. Images of empty beds function as a leitmotiv through the book and a metaphor for dreaming.

Sleeping by the Mississippi was first produced as two handmade artist's editions of 30 copies and 25 copies respectively, where the images are paired one per page. Upon seeing the book, publisher Gerhard Steidl decided to publish a large-format, trade edition, following a different but equally simple design, spare and clean like the design of Walker Evans's American Photographs: pictures on the right, captions on the left. The endnotes contain more information about some of the forty-six sumptuous color images that were taken in Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi, Tennessee, Illinois, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Both did not intend for the book to be read as reportage, although he always conceives of his work in terms of photobooks: "Work like mine is more lyrical than documentary," he explains. "Like poetry, it's pretty much useless. Anyone can take a great pictures ... but it is incredibly difficult to put these fragments together in a meaningful way. This is my goal."

Alec Soth's Dallas City, IL (2002) is available on Artspace for $5,000

Alec Soth's Dallas City, IL (2002) is available on Artspace for $5,000