Trevor Paglen ’s new Pace London exhibition Bloom is very much of the moment. A moment that's exposed an intense awareness of the fragility of our lives, cities, and economic and political institutions. A moment in which we’ve spent much of the year huddled at home with social communications reduced to awkward interactions on technological platforms designed to extract as much information about us as possible and that will likely use that information in ways we are yet to imagine. A moment that feels like it's been going on forever.

Yet anyone who's kept an eye on the artist's incredibly prescient, incredibly thought provoking, work in recent years will understand this is all grist to Trevor Paglen's mill. And in the hands of an artist such as Paglen such moments of uncertainty can also be moments of imagination, courage, and creation. With those thoughts front of mind, we caught up with him, on Zoom earlier this month to ask him about the new show. This is what he said.

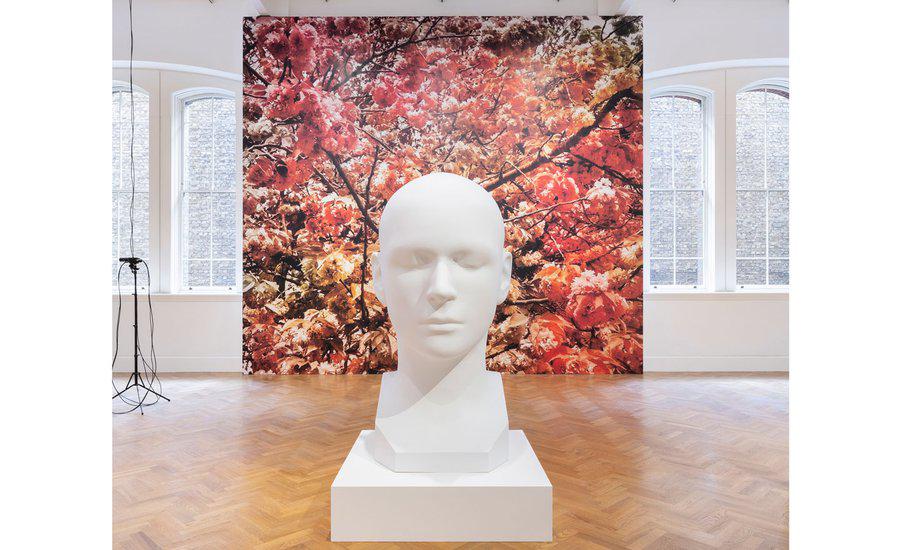

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

"Bloom has two things going on in parallel for me. One is it’s a show that was put together while I’ve been in quarantine in New York City and while there’s been a huge amount of death and a huge amount of mourning in a moment when the fragility of our lives and of our institutions is in really sharp focus and at that same time it’s a show about technology and it’s a show that uses a lot of technology looking at the degree to which our lives are kind of threaded through with AI, facial recognition, Zoom calls. So this is the moment that it’s coming out of.

At the same time while I was putting the show together it was spring and there were very few people outside, so when you would go outside you would have this overwhelming sense of fear and sadness, but at the same time you were watching nature itself explode. To me I guess the Bloom is on one hand thinking about fragility and at the same time looking at how things grow and looking at how technology companies like Amazon grow! Those dichotomies are for me what the show is about.

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

The show uses AI techniques to recreate images, a lot of these ideas around technology and AI extrapolation have been in your practice for years, so we imagine you had a basis of this show before Covid. How did the pandemic change the show? The whole show was basically done! The plan was done, we had the model and we knew what the works would be and we were going into production but then a lot of the stuff literally could not be made and we could not collaborate with people in the studio because they were in Berlin and I was stuck in New York. So I was trying to work out how to put together the show remotely and then the environment, the moment in culture just changed so dramatically. I didn’t want to address it directly but it felt like it had to be taken account of.

The relationship between images and meanings has changed dramatically in many different ways. And being aware of that and sensitive to that was important to me. But the original version of the show was more about facial recognition and classification and the histories of the relationships between measurement, power and technology. That’s still very much in the exhibition, it’s what the exhibition is about but at the same time the aesthetic language of it has changed although those things are still very much there.

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

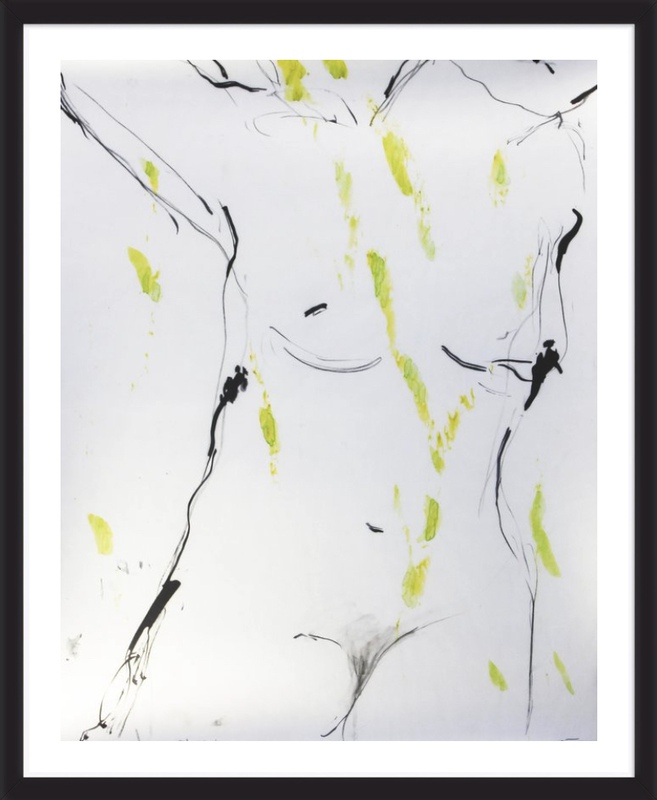

Some of the works in the show approach abstraction using high-tech methods to change an image. Do you see any overlap between the way pioneering artists broke up and disrupted image making in the 20th century, and the way machines change images in the 21st? In some of the works in the show I’m looking at computer vision algorithms and how they’re abstracting images into numbers basically. Into patterns that can be used in facial recognition and I’m going back and drawing those, and drawing the landscapes of what that algorithm is “seeing” when it looks at a landscape or a face. For me when you do those drawings they look very much like examples of abstraction from the twenties and thirties. They look very Constructivistic.

The show is actually quite broad in terms of the range of materials that’s in it. It’s almost so broad it’s hard to talk about it in one sitting. There are a lot of different things going on. Any interpretation of an image or any interpretation of a phenomena in the world is a kind of abstraction. We’re taking something that is basically infinitely complex and trying to simplify it into one concept that stands for a lot of things going on in the world. And when you create an abstraction like that, whether it’s a word or a way of seeing or a concept or an algorithm that does that abstraction, there’s very often politics involved in that.

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

The idea of 20th century abstraction seemingly revolved around the idea of a different meaning for everybody - the questions today seem more to centre on who gets to choose the meaning? That’s exactly right. There was a promise of something liberatory in the abstractions of the early twentieth century – or at least that’s the story we like to tell ourselves! The meta question there is to what extent does that idea still hold? I think the answer is pretty self-evidently no! Or at least it doesn’t hold without asking the question who is doing the abstraction and to what.

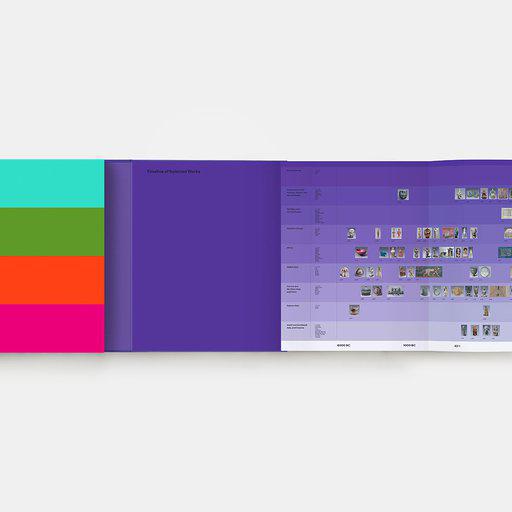

From a distance, some of the works look like beautiful colour fields, almost like Agnes Martin's. But up close they're revealed to be created from tiny texts culled from datasets used to teach computers how to recognize the sentiment of online conversations. Does it ever depress you delving into the industrialised snooping of big tech? Yeah, but it’s not debilitating.I’ve been doing this stuff a while. There is a vastly different conception of what Silicon Valley is now than there was ten years ago. And that’s good. There is definitely increased awareness about the power that technology companies have and the degree to which - on technologies like AI and facial recognition or cloud services - they really do sculpt our political and social lives in really active ways. The ability to autonomously measure sentiment on platforms like Facebook and Twitter is a major goal of AI research, with applications in everything from content moderation to user profiling to high-frequency stock trading.

I certainly think that if we pose the question of one of consent then we’re staring the conversation in the wrong direction. With a cell phone there is literally no way around it. It’s a tracking device – that’s what it is through and through. ButI don’t have a choice about having a cell phone. I have to have one to do my job. I don’t have a choice whether I use it or not. For me it’s more about how do we have a conversation about the other premises of it.

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

Some of your work focuses on research carried out by an early pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence named Woody Bledsoe who also worked on LSD and mind control programs… Yeah, I came across him years ago when I was doing research on facial recognition and came across experiments on facial recognition the CIA was funding in the Sixties. I looked around for more information about it and there really wasn’t much on it, because it was classified, basically. I reconstructed Bledsoe’s standard head from information left behind in his archives at the University of Texas. I was lucky to be able to access these documents because Bledsoe burned much of his life’s work before he died. The sculpture in the show is a reconstruction of Bledsoe’s standard head. I think of it as a kind of Platonic form of facial recognition.

I was having lunch with a post doc student in Berlin who was writing a dissertation on facial recognition and I mentioned I’d heard about these weird CIA experiments in the Sixties and she had some in her archive which she shared with me. Then I got to know a woman named Stephanie Dick and she had written her dissertation on Bledsoe and had gone to his personal archives so I started a conversation with her and she had detailed enough notes that we could recreate some of the models that he used for facial recognition in the early Sixties for facial recognition and used those models for drawings and sculptures.

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

The modeling was quite literal, wasn't it? Yes. I’ve done a lot of work looking at the material histories of technology and I am always stunned by how literal some of these histories are. I did a body of work called They Took the Faces of the Accused and the Dead which consists of images of mugshots. And if you think about something like facial recognition it kind of reminds me of biometrics and you think this conceptually is in the same ball park. But then when you look at the early work on facial recognition it’s quite literally all done using mugshots.

All the algorithms were created and crafted using mugshots of prisoners and people who were coerced into giving over images of their faces to the state. And I think you see that over and over again. Those for me are interesting historically but they also interesting because they show you contemporary things going on in life in a different way. It asks you to see what facial recognition is differently, and I think, productively.

So if basically they are compromised data sets why do we continue building technology on a hugely compromised data set?

That’s a huge question. Looking at the politics of datasets has been a huge project I’ve been doing for a while now. I think the short answer is that nobody in doing the research cares! Or doesn’t know exactly what they’re working with. Or imagines that statistically any data set will average out to some kind of fair norm or mean. I think all of those assumptions are totally wrong.

The more complicated part of the question, and this is something that Kate Crawford and I have written about in an essay called Excavating AI is that I think there is no such thing as an unbiased data set. That does not exist. You’re taking an infinitely complex world and you’re extracting it into simplified categories. Those simplifications are always going to be political and are always going to involve judgement values. There is nothing neutral about the world it’s always political. We all know that the photos we post and the texts that we write on social media and other online platforms are being used to collect information about us - information that is then sold to everyone from advertisers to insurance companies to banks and credit agencies.

Installation view of Bloom, Trevor Paglen's new exhibition at Pace in London, September 2020

Many people are talking about Covid creating different spaces where you can try new things and how this could be a cause for optimism. What are the things for you that are optimistic about all this? I’m generally not somebody who really likes the word optimistic very much. For me it always implies a lack of agency. Oh we’re just going to hope that things will be OK. So there’s a part of me that immediately objects to that and just wants to do something rather than just be optimistic. So I don’t like the word optimistic but I’ll use it. I think it’s very obvious that the inequities in American society certainly have been laid very bare and it’s been very obvious what the deadly consequences of that are. And that can, hopefully, perhaps, be a catalyst for some kind of change in some cases. I think there are huge opportunities for self-organising, and we’ve seen this on a massive, massive scale this year. So that’s a huge source of hope I think there are lot of indicators that seem to suggest that huge numbers of people are invested in trying to rebuild society in ways that that are more just and more equitable and more joyful.

You mentioned Kate Crawford, who I’ve collaborated with a lot, and she has done a huge amount of work to really change what the common sense is. To some degree in industry but certainly in academia around AI and classification. If you had gone to a machine learning conference five years ago and given a paper about bias or racism in machine learning you would have been laughed out the room and now this is an established field and people are trying to understand the problem.

You joined Pace recently, what attracted you to the gallery? I’m really happy to be working with Pace. They provide a way to be able to be able to work in different places in the world simultaneously and it’s obviously a huge honour to me to be on a roster that has been hugely inspiring to me since I was a child. It’s a place where I have a lot of really ambitious projects that I want to do and it’s a structure that I can grow with. I think everyone in the art world is waiting to see what sticks around right now. When things come back it’s going to be very different.