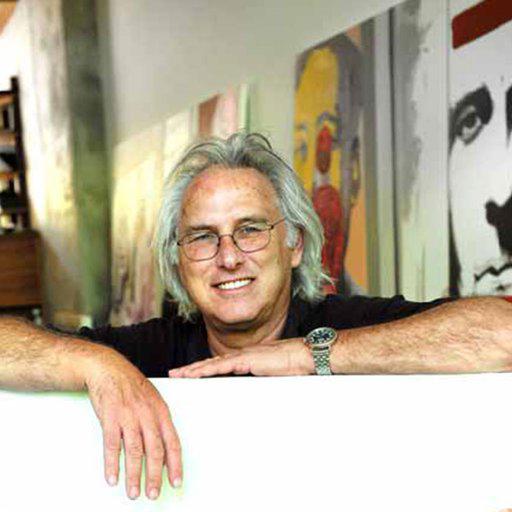

The big name guest interviewers conducting the Q&A’s in Phaidon’s Contemporary Art Series of monographs usually tend to come from fine-art backgrounds. People such as Hans Ulrich Obrist, Okwui Enwezor, Linda Yablonsky and Charles Gaines have all featured in the books.

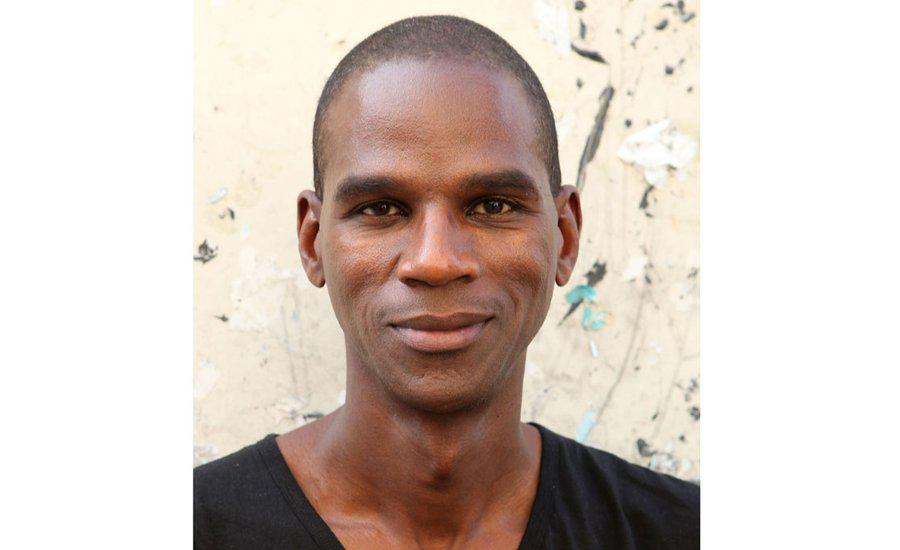

Mark Bradford’s choice was a little different. For his Q&A he selected Anita Hill, the US academic and attorney, who rose to prominence in the early 1990s, after voicing sexual harassment claims against the US Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.

Hill’s hearings were televised, and Bradford, then a young employee in his mother’s beauty shop, was struck by her presence. “You were actually the first black person that I ever saw standing up in public,” he says in the interview, first published in

Phaidon’s Mark Bradford Contemporary Artist Series book

. “My mom had a television in the shop. All I kept thinking was that you were telling a counter narrative; you weren’t supposed to do that. I remember thinking there was something inside of me. I identified with that. You were black and you were telling on somebody black. I’d never seen anything like that.”

Questions of abusive violence and counter narratives are key to Bradford’s own work. Though he remains an abstract artist, vital and all-too-real themes of sexual and racial prejudice, community displacement, and hidden geography, can all be felt within his work, which often includes socially significant ephemera, such as hair perming end papers, bleaching agents and scraps for billboards.

Read on to understand how this singular artist went from the beauty shop to the Venice Biennale, all while remaining the same wide-eyed, open-hearted individual

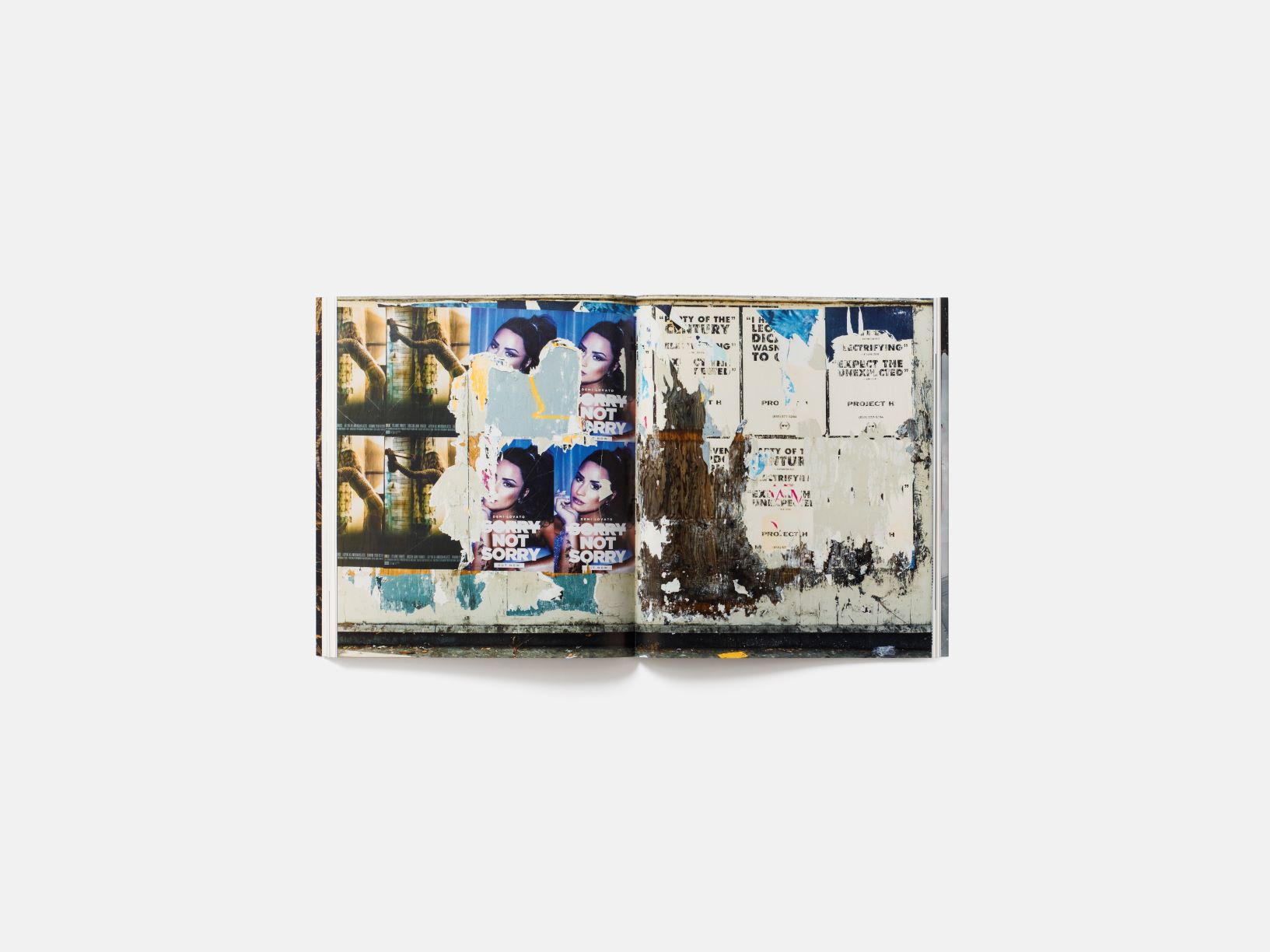

Mark Bradford,

Niagara

, 2005, video, colour, 3 min. 17 sec. Artwork © Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford,

Niagara

, 2005, video, colour, 3 min. 17 sec. Artwork © Mark Bradford

ANITA HILL: We first met at the Rose Museum on the campus at Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, in October of 2014. We talked about a lot of things, but in particular, we talked about your mom’s beauty salon in Los Angeles – eventually it was in Leimert Park – as a place where your exposure to art began. You told me that the way you think about art, how you present it, and the process of creating it started with your experiences in the beauty salon.

MARK BRADFORD: I worked in a beauty shop. ‘Salon’ is an integrated term. It covers all races. The beauty shop is particular to black America. It’s an older black America, non-integrated, servicing the local black community. When you think of press and curl, you think of the beauty shop. Then we moved into relaxers and flat irons and it started to become a beauty salon. I was a beauty operator. My mom was a hairdresser. Now they’re stylists.

HILL: That’s the cultural and business transition. You said that you see the beauty shop as a public space. It seems to me that so much of what’s happening there, the hairdressing and conversations, is personal. How do you see the shop as a public space?

BRADFORD: It was both, public and private. What I meant by ‘public’ is that it’s like people at train stations, airports, bars, nightclubs – all places I like, by the way – it creates this bond, like at a concert. We’re here for this amount of time, sharing something and then everyone goes back to their private spaces, their homes. But for that moment, when they’re in that public space, magic can happen. Everyone is in the conversation and they share and reveal things. Sometimes it was easier for the women to reveal things to near strangers than to their families. I’d be amazed sometimes when I watched two women under the dryer who really didn’t know each other and then I would listen to the conversations. They’d have these intensely private relationships for an hour or two and then they’d go back to their lives.

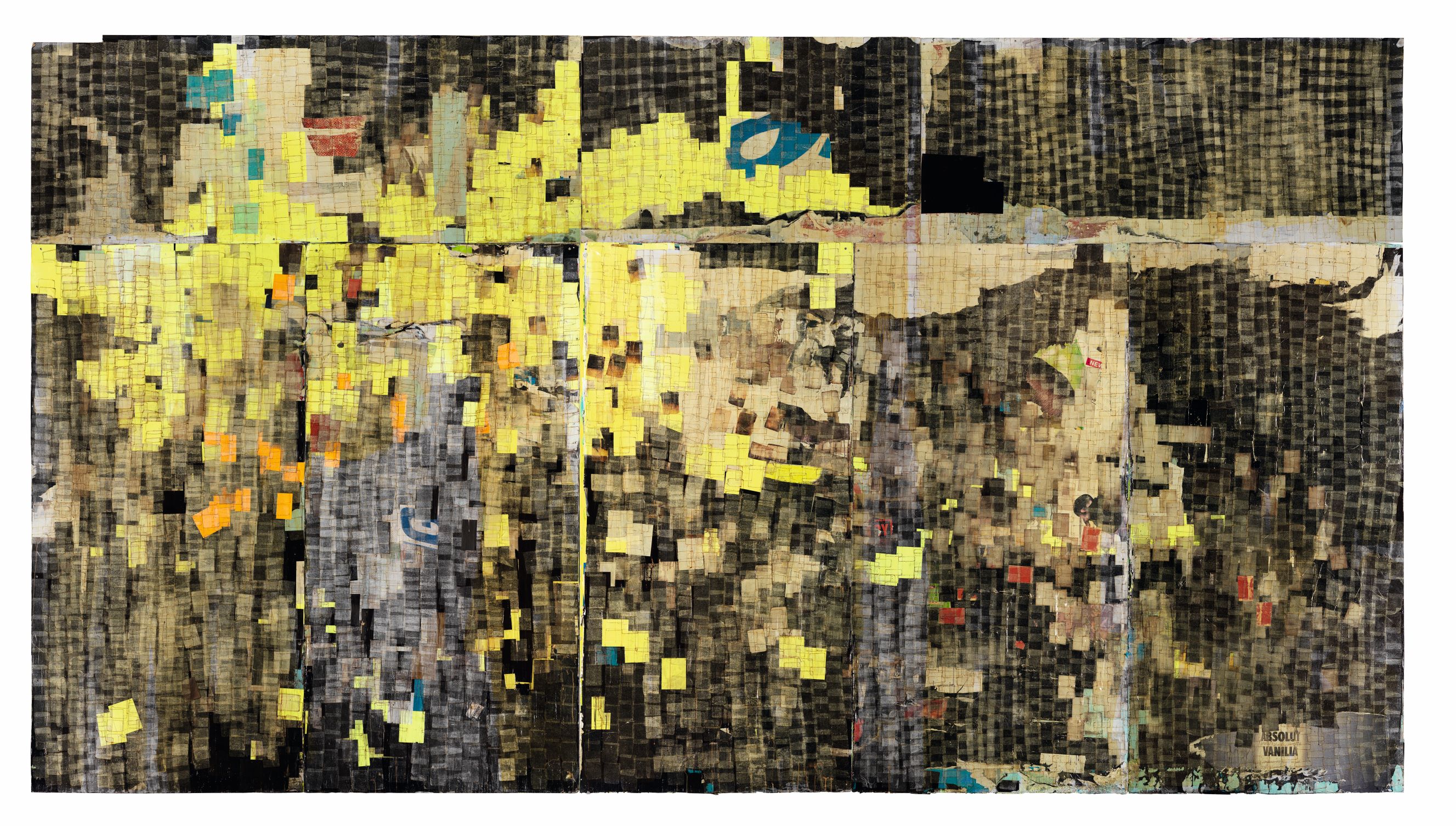

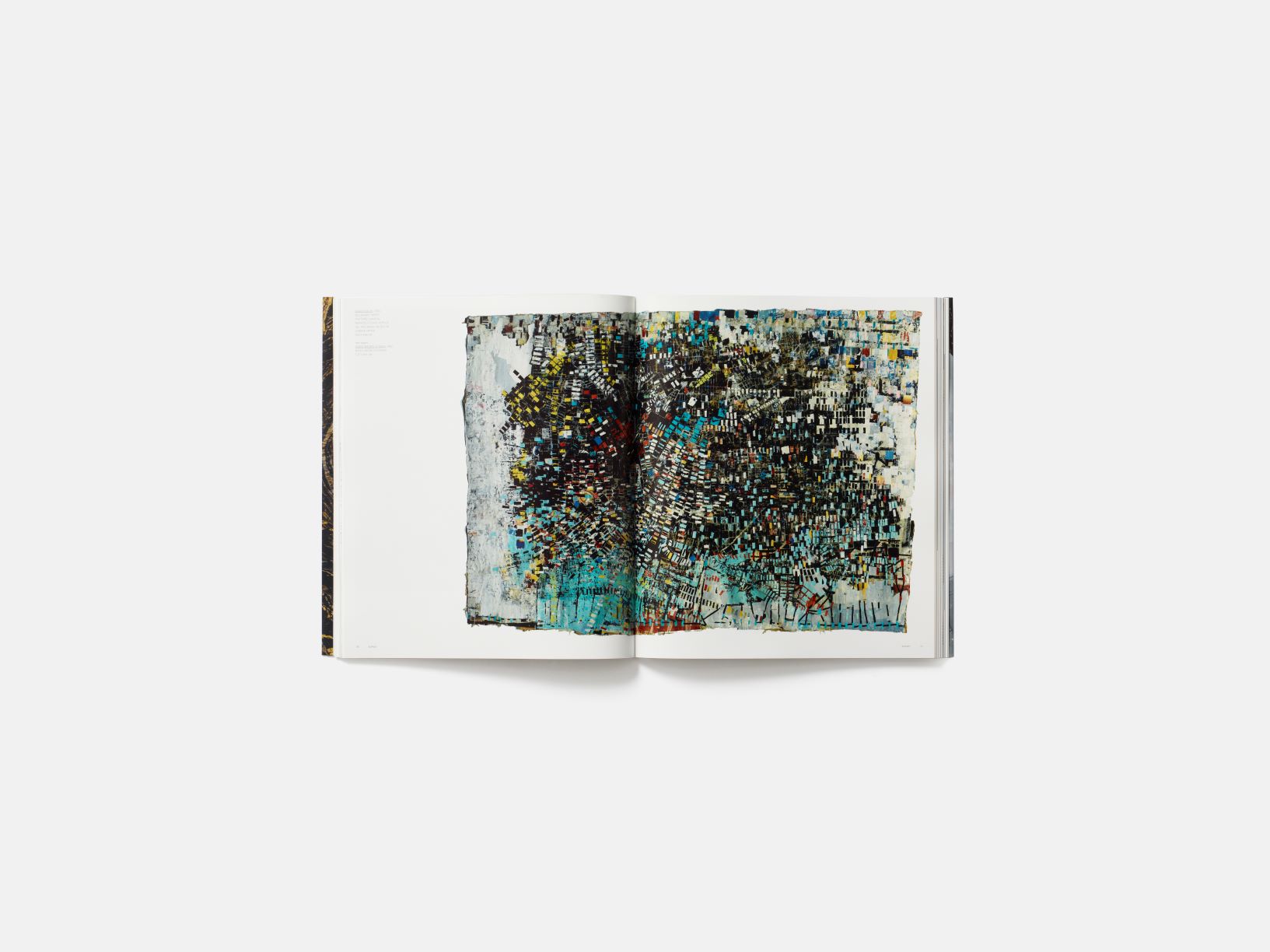

Mark Bradford,

Let’s Walk to the Middle of the Ocean

, 2015, mixed media on canvas, 260 x 366 cm. Artwork © Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford,

Let’s Walk to the Middle of the Ocean

, 2015, mixed media on canvas, 260 x 366 cm. Artwork © Mark Bradford

HILL: The way you describe the space makes me think of it as a gallery or stage of sorts. Did you know these women in other contexts?

BRADFORD: It always felt weird to me when I met them outside of a hair salon. They were with their children, husbands or friends and it felt totally different from when we were in the beauty shop. You couldn’t have the same conversation.

HILL: Was the beauty shop a therapeutic space?

BRADFORD: Surely it must have been, because a lot of times the women felt safe. They might be in different stages of undress, noone’s really putting on airs … So probably, yes, the sharing was therapeutic. What was really interesting about my mother’s space was the fact that a black woman owned it. She was the entrepreneur – the merchant – and she ran it in her own way. It wasn’t like in the church, where it was male-dominated.

HILL: Would you say that your mom created a gendered space where women shared experiences that were particular to their gender and race and often class as well?

BRADFORD: This was a woman’s space. My mother’s voice was listened to. People would come by the salon just to talk to Janice. She had a strong presence and she shared a lot and gave a lot emotionally and physically.

HILL: What time frame are we talking about?

BRADFORD: The 1970s. We were coming out of the Civil Rights era and coming into a time when black people were really moving forward in the system. Young, gifted and black. There was a lot of excitement and momentum. Black people owned their own homes. Everyone was motivated to move forward. And I was a young child caught up in the thrust forward.

Mark Bradford,

Finding Barry

, 2015, excavated wall painting, 645 x 1443 cm, installation view at The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2015. Artwork © Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford,

Finding Barry

, 2015, excavated wall painting, 645 x 1443 cm, installation view at The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2015. Artwork © Mark Bradford

HILL: Tell me more about the clientele, the women in the shop. How were they moving forward?BRADFORD: My mamma’s customers were all black; over 50 percent were raising kids. We’d have to work late. My mom had a lot of clients from DWP, Department of Water and Power – the phone company. I can see them all under the dryer, all studying. All of them were in school at night to get their Bachelor’s or Master’s degrees. My mom’s clients were the same age as she was, in their late twenties. Through the years, I inherited her clients.

HILL: Ah. You heard about women’s lives from their late twenties up until ...

BRADFORD: They passed away.

HILL: You’ve already positioned them in the Civil Rights movement. There are black people owning things. They’re moving and building equity and status in the community – building community. In the 1970s and 1980s, from the very public side, you’d think this was a great time for these people. Was that true of the private side of their lives too?

BRADFORD: No, it was up and down. On the private side, they were navigating men, navigating relationships that weren’t good. Abuse, drugs, mental illness, depression, children who fell through the cracks … Children went to prison, especially when you move into the 1980s with the crack-cocaine epidemic. Some women were raising their grandchildren because their daughters were on the streets. I never say ‘angry’ black women. I never knew what that was. I saw women who were sometimes stern because they had to be. I saw the most generous spirit towards me that I’ve ever experienced. These women were moving up the corporate ladder and oftentimes they were moving faster than their husbands. Violence and spousal abuse, definitely.

HILL: Sexual violence?

BRADFORD: Oh yes, absolutely. That was across the board. You’d hear it matter-of-factly. Someone would tell about something that happened and someone else would say, ‘Oh, that happened to me.’ Then another person would say, ‘That happened to me, too.’ I think my mother created a non-judgemental space where her customers could share things.

HILL: There’s the therapeutic space and then there’s the creative space. They’re not separated. It seems that your mom’s real strength was in the creative side of it.

BRADFORD: My mother could take a head of hair and make magic. She would sculpt it. She was always late. She would take forever. If my mom was working on your head, she’d work until the last moment, until it was perfection. It was art for her. It was sculpture. Interestingly enough, I talked to my mom this morning and she was on her way to sculpture class. She’s always been very talented with her hands. I watched her from five, six, taking her time. It was art. My mom was always a little artsy and a little kooky. She wasn’t really trying to be middle class or upper class or lower class. She was fluid because she didn’t have parents. But I never heard my mom belabouring not having parents or feeling like there was a problem with it. She did feel that she was operating on the fringe of society though.

HILL: Did you feel that you were on the fringe?

BRADFORD: Yes, I did. I was born into it. My mother was always straightforward and unpretentious. I have her last name. I loved having her last name. I didn’t even know I was a bastard until I was thirteen. A woman registering me for something told me I was a bastard. It didn’t bother me. There’s something that I liked about the fact that I was illegitimate.

Mark Bradford,

The Devil Is Beating His Wife

, 2003, billboard paper, photomechanical reproductions, permanent-wave end papers, stencils and mixed media on plywood, 335 x 610 cm. Artwork © Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford,

The Devil Is Beating His Wife

, 2003, billboard paper, photomechanical reproductions, permanent-wave end papers, stencils and mixed media on plywood, 335 x 610 cm. Artwork © Mark Bradford

HILL: Did it bother you that you were on the fringe?

BRADFORD: No. I always knew what I was and I always knew what other people said that I was. I always felt that I could be in the centre and that I was powerful. But I was born more on the fringe.

HILL: I like that you always felt that you were powerful. Do you have any idea where that came from?

BRADFORD: I knew something had happened. I knew somebody had pushed me out. I didn’t belabour it much. I started walking the earth. I got it from the community and from the boys who grouped up in the schoolyard. I started walking and exploring – exploring what I could – and what I couldn’t, I stayed away from until I grew bigger or stronger or knew more. And as I knew more I could inch closer and closer and closer.

HILL: You said your mom told you that you had to navigate – somehow figure out ways to cross the schoolyard alone.

BRADFORD: I had to navigate. I think that that came naturally to me because my mom navigated. I felt like if she could navigate this unusual community that she navigated in, then I certainly could. I knew that I was never going to go to formal society and ask for help. I knew that they were going to judge me as bad. I said, ‘Never mind. I got this. I’ll figure it out.

HILL: What was life like for you in LA in the 1970s and 1980s?

BRADFORD: I was working as a hairdresser, travelling all the world, basically partying and working, doing clubs. I didn’t really have relationships. I’d be in and out of this and that, but I never really locked down too much. I was streets. Randy Crawford’s ‘Street Life’. That’s me, honey. That’s what I did.

HILL: That had to be an influence on you. What were the clubs in Los Angeles like at that time?

BRADFORD: I went to all of them. Gay, straight, black, white, Mexican, Chinese, you name it. I liked nightclubs. It was the same feeling I had in the beauty shop. It was this public space where all these private things were going on. People could be whoever they wanted to be. A woman who’s working in a bank every day could put on this disco dress, go to the club and shimmer all night. She could do her thing. She could have a different name. I didn’t care what her name was. I was like, ‘You look fabulous. Let’s twirl all night long.’ I love that space of creativity and being anonymous at the same time. Although I got labelled as girls do – fast, street, promiscuous, all that stuff –I liked going out and dancing and being in the nightclubs. Make no mistake, there’s a dark, dark side to it. You get caught up and your body gets eaten up: destroyed by drugs, sex, AIDS, violence. I was always aware. Violence has never left me. I wish it would at some point. It’s always part of my narrative. I think women can understand that more. Violence never, ever fully leaves my context. I turned a street corner last week and a guy said, ‘Oh, there’s a faggot.’ Still, at fifty-four years old! The same thing as a woman. A woman never loses the feeling that she could be sexually assaulted.

HILL: In the streets, the threat is always there.

BRADFORD: Absolutely. It will never, ever leave me fully. That’s my reality.

HILL: Was there something about the 1970s and 1980s with so many threats that made you personally think that death was inevitable?

BRADFORD: Anita, I was completely haunted from seventeen years old. Haunted. I look back now, and see I was deeply troubled. Deeply. It was horrifying – I was seventeen, eighteen, nineteen – when AIDS hit. And because they pointed to certain groups of people and because I was in those groups of people, it completely knocked me out of any type of stability that I had. For my sins, I was going to die. It was biblical for me. I’m black. I come from the black church. You’d have to take a friend to his mother and say, ‘Your son’s in the car. He’s dying and he’s gay’ – all in the same breath. There were so many men dying in the black church. It’s like the curtain got thrown back. It was a monster. I watched 75 percent of the people that I knew die.

HILL: You didn’t think you were going to live?

BRADFORD: I didn’t think I was going to live. The doctors told me I wasn’t going to live. They said, ‘You got good news and bad news. What do you want? The good news or the bad news?’ I said, ‘Well, give me the good news.’ ‘You don’t have AIDS. The bad news is you’re going to get it.’ I said, ‘Why?’ ‘Well, people like you get it. That’s inevitable. Get your house in order.’ I thought, ‘Okay.’ I wasn’t even twenty-one.

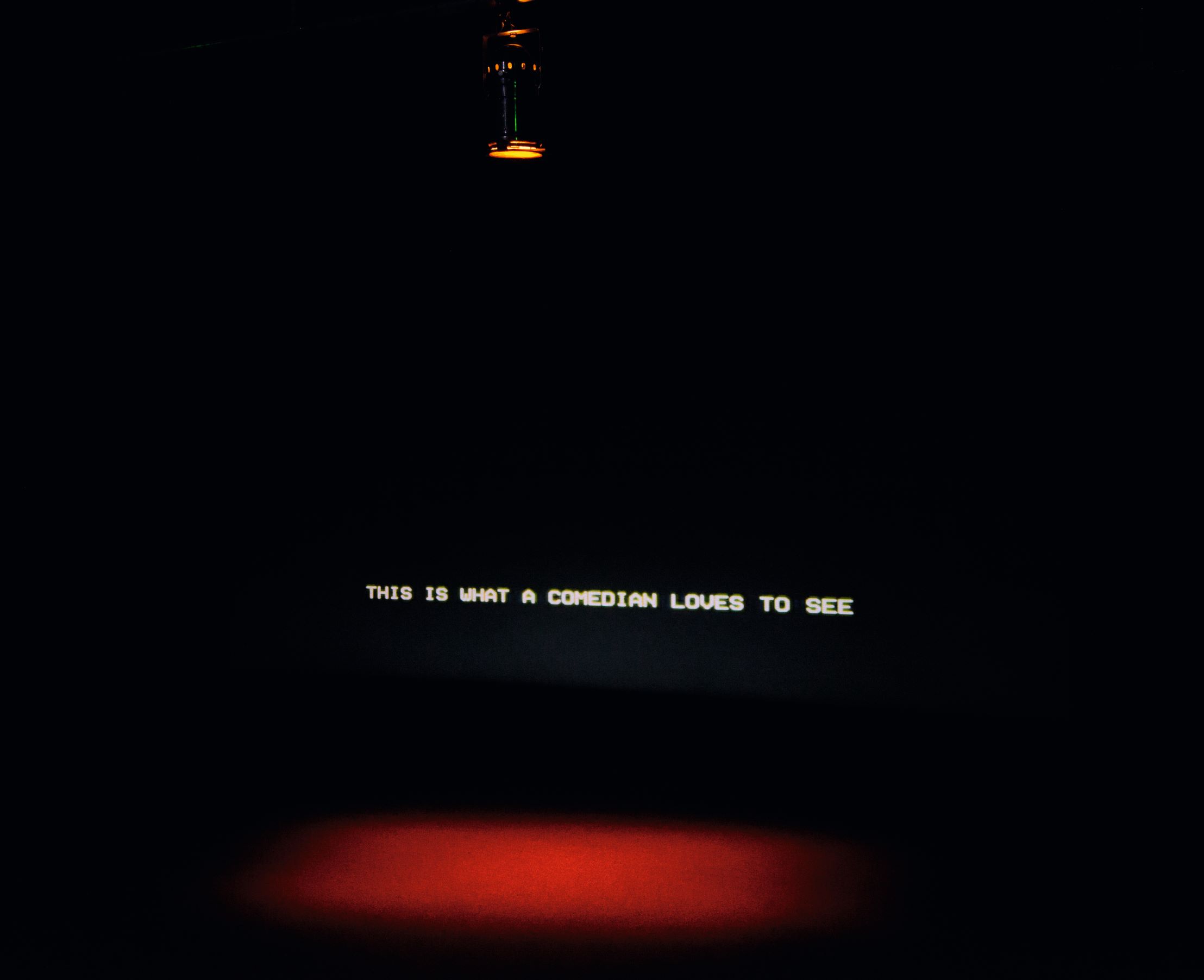

Mark Bradford,

Oracle

, installed in the US Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale

Mark Bradford,

Oracle

, installed in the US Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale

HILL: That was the dark side of street life in the 1970s and 1980s, but there was also a creative side.

BRADFORD: Whatever you’re into, they have it in the streets. At the same table, I might have been into dancing but the one right next to me was into the drugs and the one right next to him was a prostitute. The one right over here was a pimp. It’s not like it wasn’t all there. The streets call for whatever you’re into. I was into the performance of it.

HILL: Was all of what you were doing and what other people were doing performance?

BRADFORD: I realize now a lot of it was performance art. I would make these elaborate costumes and dance routines. Me and my girlfriends and boyfriends, we’d play characters and do all kinds of things: Voguing. By the time Madonna got to it, I was pretty much done with it.

HILL: At some point you did go into ‘formal society’. And art school was part of that decision.

BRADFORD: Yes, I did, but it was hard. I was struggling from twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-nine. I’d learned so many bad patterns around education. I didn’t have the tools. I had the milk and not the cereal. That was so overwhelming to me that I’d become despondent when I went to the office and they’d show me the records of what I hadn’t done, how I had to get my GPA up ... I didn’t even know what a GPA was. Those standardized tests, I would make Christmas trees on them. All that stuff came back to haunt me. It would be so overwhelming that I’d do one semester, mess up, get put on probation and go to another school. From about twenty to about twenty-seven, I was going constantly to Europe and coming back, working in the hair salon and then I’d go party. But there was a deeper sense, which I’d only admit to when I was by myself, that this wasn’t enough. That was a frightening voice to me. Girl, I went to every community college in LA – West LA, Los Angeles, Santa Monica – but the one that clicked was Los Angeles City College. Most of those people were older students, foreign students going to school at night and they were serious. Somehow I fit. I was hungry enough and desperate enough, I guess. That’s why I know what it’s like to have a school record that has so many gaps in it, when you’re going back to school and trying to do something and you have this old life pulling on you so strong, telling you, ‘What the hell you doing all this for?’

HILL: In the 1990s, with your time in the shop and in the clubs, did you think that you were an artist?

BRADFORD: I knew that I had such a strong background in materials and texture and colour, from working with hair for so many years and from the clubs, that I had a good mastery of materials.

HILL: You had knowledge and ability that came from your experiences. What did you want from art school?

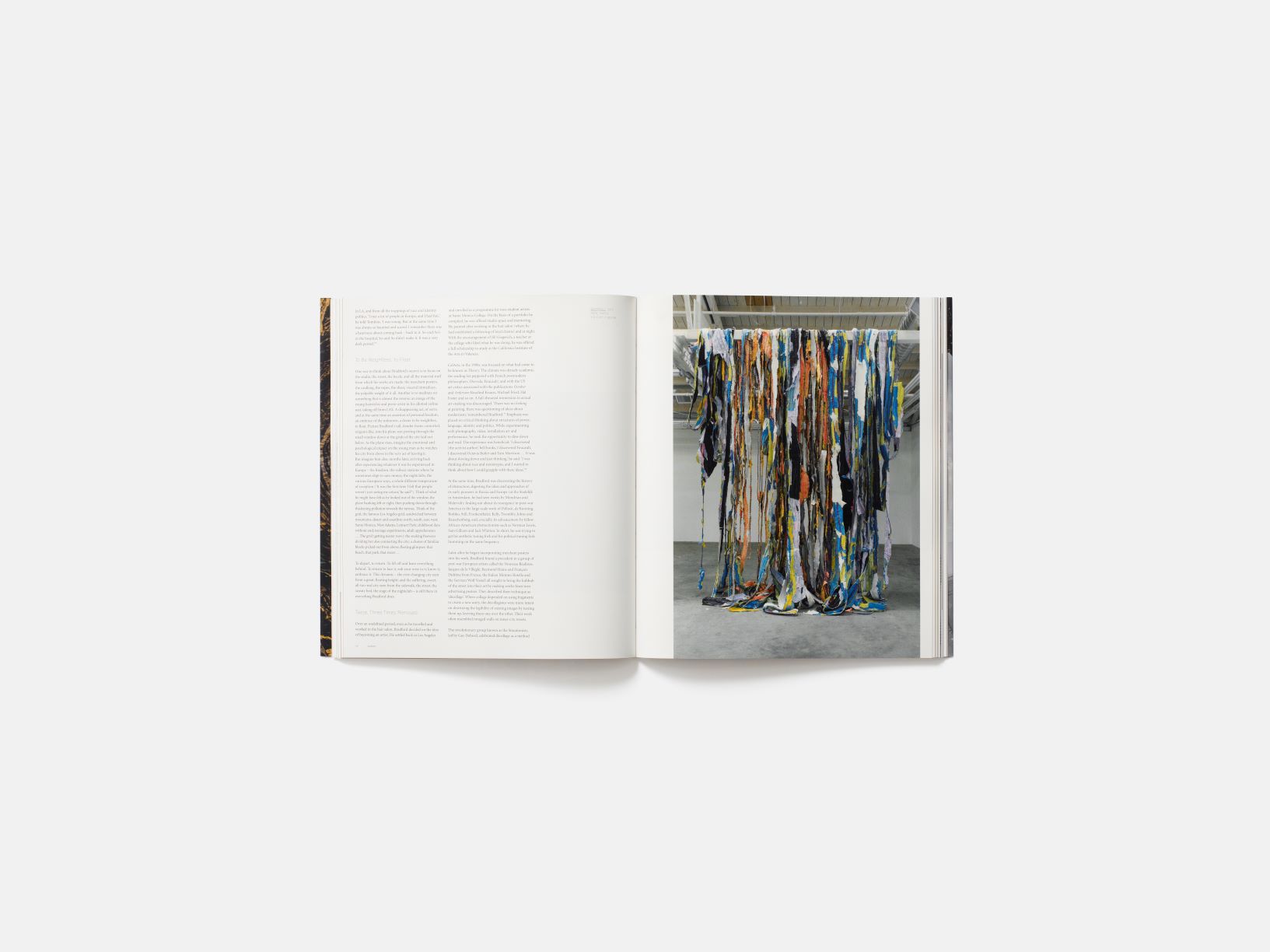

Installation view of Spiderman, 2015, by Mark Bradford

Installation view of Spiderman, 2015, by Mark Bradford

BRADFORD: I remember thinking, ‘I need to go to a school that has ideas.’ CalArts was a school of ideas. You read. That’s what you do. You read, you process, you think. For me, because I had a strong material side, I thought that that was a great place to go. I entered CalArts at thirty/thirty-one. What I was interested in learning about was ideas. I stumbled on a little bit of feminism through reading Octavia Butler and Angela Davis. It opened up my eyes to the fact that a lot of women were challenging the system and standing up and speaking in voices that were not just of the status quo. I’d never seen that before. You were actually the first black person that I ever saw standing up in public. My mom had a television in the shop. All I kept thinking was that you were telling a counter narrative; you weren’t supposed to do that. I remember thinking there was something inside of me. I identified with that. You were black and you were telling on somebody black. I’d never seen anything like that. You were standing up and not being on the fringe. I think before, you were on the fringe, to be honest with you. You stood right in the centre and put your hand up and said, ‘There’s a problem.’ I’d never seen that before. That was something! I said, ‘How can she do that? We’re black people.’ I’d never seen that before. I said, ‘Oh, I know what that is.’ They started calling it feminism: speaking your truth to people who may not agree. I was like a ghost on the fringe: keep moving until they see you run. I never thought to say that there was a problem.

HILL: Does your art become your truth?

BRADFORD: Oh lord, yes. Yes, it absolutely does. It’s always me walking into the middle of the room and saying my truth whether I like it or not. Sometimes I do wish my art wasn’t so vulnerable. Then I remember that delicate person standing right there. That’s something that burned into my memory and I do that with every piece. For me, it’s not about existing on the fringe; nor is it about the people existing on the fringe. It’s actually about us pushing ourselves into the centre – alternative voices pushing into the centre: women’s voices, people who are not deemed proper.

HILL: I’m not an artist, as you know, and frankly I know less than I should about art …

BRADFORD: That’s too bad. Your eyes are clear.

HILL: But there are a couple of things that I keep coming across when people are describing your art – social abstraction and Abstract Expressionism. How do you see your art?

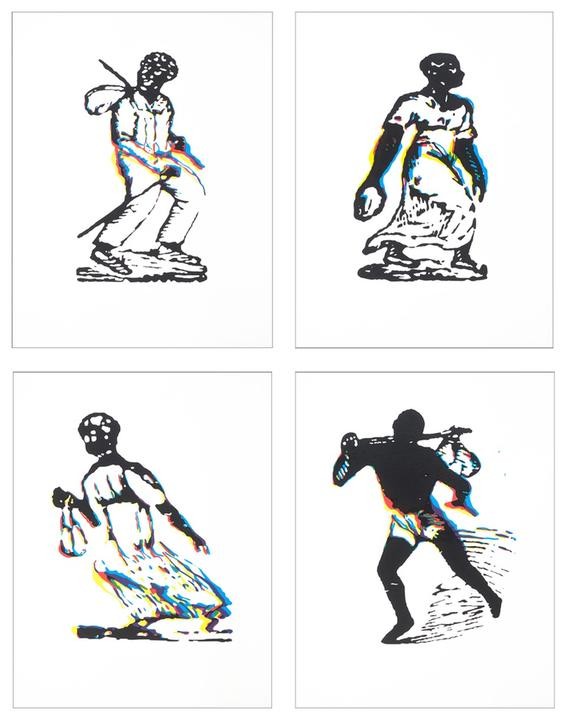

BRADFORD: I can tell you what I know. I can tell you the impulse that I had. I thought that I wasn’t going to let anybody tell me what to do and how I was going to do it. I decided that I was going to take all my experiences in the world and all that material from the world – the detritus of the world that we live in, the billboards, the stickiness, the messiness – I was going to take all that, I wasn’t going to use a drop of paint and I was going to push myself into the centre of the room. That’s what I did. It’s not just abstraction. Abstraction for me, I get it – you go internal, you turn off the world, you’re hermetic, you channel something. No. I’m not interested in that type of abstraction. I’m interested in the type of abstraction where you look out at the world, see the horror – sometimes it is horror – and you drag that horror kicking and screaming into your studio and you wrestle with it and you find something beautiful in it. That’s what I was always determined to do. I have never turned away. As a child in the hair salon, I never turned away from horror. I saw it all. There was so much strength and so much beauty too. The laughter in between the crying. I believe in that. For me, I was going to drag it all into the studio and then I was going to drag it out to the gallery. Yes, in a way it is social abstraction. The thing about Abstract Expressionism that fascinated me was the fact that so many African-American men and women have been left out. It was also really fun when they told me, ‘Oh Bradford, you can’t. Don’t do that.’

HILL: Is the way the public sees abstract art racialized, in particular, white and male?

BRADFORD: That’s the way that it was constructed in the 1950s, but no, I don’t buy that. If you look at certain tribes in Africa, they’ve always had a long history of abstract art. Abstraction doesn’t belong solely to the Western canon of art. Islamic art is all abstract. Islam believes you should never depict God. It’s all done through abstraction. I feel the same way. I’m not going to depict horror by showing horror. You’ll get to it with that abstraction. There’s some stuff going on there. It pulsates with whatever I want. I will never show it. No. I won’t.

HILL: I was reading a couple of days ago that recently a large collection of twentieth century abstract works by Latin American artists has been donated to MoMA. It seems to have turned what people were thinking about Latin American art on its head.

BRADFORD: Same thing.

Mark Bradford,

Mithra

, 2008, mixed Media, 2134 x 610 x 762 cm, installation view at Prospect. 1, New Orleans, 2008. Artwork © Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford,

Mithra

, 2008, mixed Media, 2134 x 610 x 762 cm, installation view at Prospect. 1, New Orleans, 2008. Artwork © Mark Bradford

HILL: Is it possible for us to restore the place of black artists in this part of the world in this form?BRADFORD: Absolutely. One of my ideas that I’m really interested in promoting is that we, like any other people, can and should be allowed to be private and not to have to explain our stories through figuration. We should have the right to be abstract. Why not?

HILL: When you said, ‘I’m going to CalArts to study ideas because I know materials’, were you thinking then that you’d be doing abstract art?

BRADFORD: Oh no. When I got there? Are you kidding? With all my stories, the hair salon and all the travel? Oh no! They wanted me to talk about gender, race, sexuality, the whole gay thing. Oh my god, they were always pushing me. I played, played, played and I said, ‘OK, I’m going to start being an abstract painter.’ They were like, ‘Wow, you’re going to be an abstract painter?’ I remember a teacher told me, ‘You’re giving up so much.’ I guess there’s so much I could pull from, right? But I wasn’t going to let anybody push me. I’d been pushed enough in my life when I was wandering, but I wasn’t going to have anybody push my stories out of me before I was ready to tell them. The first thing I did was with end paper – abstract paintings. I wasn’t going to reveal much, but slow, slow, slow, slow. I wasn’t going to have anybody tell me how fast to reveal my soul.

HILL: You started out with end paper from the salon, because of the material?

BRADFORD: It was cheap. I didn’t have money. I was working in the hair salon. I liked it. I loved it. I didn’t have to give away these women’s stories, but yet it pointed to this space. It was a material that I loved working with. It had social history and memory to it. It had location. It was my magic carpet. I loved everything about it – totally different from the reasons the art world loved it: fetishized in a fish bowl. I didn’t want to dig myself into the hole of the hairdresser artist.

HILL: You have so many stories and your own story is so interesting. Do you ever worry that it will eclipse your art?

BRADFORD: I don’t care at this point. Caring means that I would have to start editing out. This is the way I think of it: my art exists and it’s out there; it’s all over the world. As long as the art is out there, my story will never eclipse it. But if my art has to be very, very intimately tied to my story, then so be it. I talk from the gut a lot of times. I often think, especially in the art world, they want to separate the art from the person. I have no interest in that. I started too late. I was out of school at forty. I’d led so much life. It would be unbelievably difficult.

HILL: You want to talk about your work? Can we start with ‘Sea Monsters’, your exhibition at the Rose Museum, where we met? I find your ideas about the trade routes fascinating.

BRADFORD: I tend to go to politics and anthropology more than I go to art history. It’s natural for me. Politics and anthropology live in a world of people. Art history is this tomb and art theory is a tomb. I’ve always been interested in maps and trade routes. For my people, how I got here, the Middle Passage and trade were linked. We were basically a currency that they brought from Africa and dropped off in the Americas. The early seafaring maps would be loaded up with these mythological creatures that existed in these oceans. The first mapmakers portrayed the sea as a scary place to dissuade others from going there. It was all myth on top of myth. These creatures weren’t real. While they plundered, early explorers would use their maps to keep everybody else out. This idea that monsters exist under the sea but you can’t see them fascinates me. They’re the dangerous unknown. Basically, it’s calling otherness I liked it. I loved it. I didn’t have to give away these women’s stories, but yet it pointed to this space. It was a material that I loved working with. It had social history and memory to it. It had location. It was my magic carpet. I loved everything about it – totally different from the reasons the art world loved it: fetishized in a fish bowl. I didn’t want to dig myself into the hole of the hairdresser artist.

HILL: You have so many stories and your own story is so interesting. Do you ever worry that it will eclipse your art?

BRADFORD: I don’t care at this point. Caring means that I would have to start editing out. This is the way I think of it: my art exists and it’s out there; it’s all over the world. As long as the art is out there, my story will never eclipse it. But if my art has to be very, very intimately tied to my story, then so be it. I talk from the gut a lot of times. I often think, especially in the art world, they want to separate the art from the person. I have no interest in that. I started too late. I was out of school at forty. I’d led so much life. It would be unbelievably difficult.

HILL: You want to talk about your work? Can we start with ‘Sea Monsters’, your exhibition at the Rose Museum, where we met? I find your ideas about the trade routes fascinating.

BRADFORD: I tend to go to politics and anthropology more than I go to art history. It’s natural for me. Politics and anthropology live in a world of people. Art history is this tomb and art theory is a tomb. I’ve always been interested in maps and trade routes. For my people, how I got here, the Middle Passage and trade were linked. We were basically a currency that they brought from Africa and dropped off in the Americas. The early seafaring maps would be loaded up with these mythological creatures that existed in these oceans. The first mapmakers portrayed the sea as a scary place to dissuade others from going there. It was all myth on top of myth. These creatures weren’t real. While they plundered, early explorers would use their maps to keep everybody else out. This idea that monsters exist under the sea but you can’t see them fascinates me. They’re the dangerous unknown. Basically, it’s calling otherness rappers. We have oral history. Black folks have always had oral history. I understand that. That’s my lineage.

HILL: In a way, isn’t it still the threat that triggers creativity and expression?

BRADFORD: Oh yes. The feeling that there’s always a threat.

HILL: Right. Scientists now say that they can actually trace that trauma genetically – that intense psychological trauma can be passed from generation to generation in our genes, altering how we relate to stress.

BRADFORD: I absolutely believe that. Again, I take strength and I take joy from that legacy. I take all kinds of things. It’s a source of support for me.

HILL: Drugs and HIV/AIDS show up prominently in your show ‘Scorched Earth’ at The Hammer. Certainly in the 1980s HIV/AIDS was a threat to entire communities that you were in.

BRADFORD: That was a hard show. I was very uncomfortable doing that show.

HILL: But you pushed past your discomfort, and with your map showing how many HIV/AIDS patients had died nationwide in the 1980s, you said you really started contemplating the role of policy – how policy determined how many people died, and how different policy could have meant a different outcome.

BRADFORD: Yes. You look past your personal story to policy. Why are certain areas the way they are? Why aren’t there more services in certain areas? You realize that a lot of what we’re talking about is policy and someone put that in place for a reason. We weren’t in the room. The policy, the law, the constitutions, the amendments, these are things that people go back to when they’re making their final decisions. I became fascinated with that.

HILL: Policy can be a decision to do something affirmatively or not to do anything at all.

BRADFORD: Absolutely, it can be both. It can be active aggression. It can be the silent killer in the room.

HILL: ‘Scorched Earth’ was also intriguing because of the reference to the Tulsa Race Riots, which occurred, not in 1980s and 1990s Los Angeles, but in 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma. More specifically, the Greenwood section of Tulsa, which was a black metropolis. Can you talk about the relationship between the AIDS epidemic and the policies and the Tulsa Race War and how you saw those three things fitting together?

BRADFORD: About four years ago, I did a painting called Scorched Earth that was about the Tulsa Race Riots and the bombing of the whole merchant black community in Tulsa. Very few people knew that there was a race riot in Tulsa. Very few people knew exactly how brutal it was. I’m sure you know this. There are two trains of thought: yes, Americans did drop bombs on the community and no, they didn’t. I believe they dropped a bomb.

HILL: In fact, there’s new evidence, a first-hand account written by a man who saw planes flying overhead dropping tar balls that were the equivalent of bombs on top of houses. Houses were burning from top down, not ground up.

BRADFORD: Right. That’s how I came to this. I remember doing some research and I came across this idea that America’s never dropped a bomb on American soil and I thought, ‘Oh, isn’t that interesting?’ It’s actually not true. They have dropped a bomb on American soil, in the centre of black Tulsa over a trumped-up charge. It was a hugely dynamic centre. I think it was becoming too strong and too big and too powerful. I think they wanted to get rid of it.

HILL: Do you see a parallel between what happened in Greenwood and what the map shows?

BRADFORD: Absolutely. Maps are nothing but the biggest lies on the planet. They’re only the physical manifestation of power.

HILL: To me the AIDS map is a ‘scorched earth’ map. It seems to me that if you look at that map and you see how many people have died, you wonder what kind of policy allowed or even caused it.

BRADFORD: Absolutely, because of power. People lost their lives because of policy. I watched them first hand. I was among the first hundred people to ever get tested. They didn’t have a testing centre. I signed up and we went to this bunker out somewhere. It was crazy. There were hazmat suits. Awful! Anyway, guess what? It wasn’t anonymous. I didn’t test positive, but most of the people that were tested, tested positive. It went into their records. Then about six months later they developed anonymous testing. All those people who had been tested before couldn’t get health insurance because it was in their record and no insurance company would carry them.

HILL: They weren’t required to.

BRADFORD: No, they absolutely were not required to. Again, that was policy.

HILL: In the Hammer Show you continue to look at policy in South Central Los Angeles.

BRADFORD: Here’s the thing, in South Central in the 1980s, on every corner there used to be churches or liquor stores. Liquor stores are gone. Then there came a flood of crack cocaine. Crack cocaine was everywhere. But we lived through that. Now, on every corner, there’s a medical marijuana clinic. I can go down Crenshaw Boulevard, and in a two-block radius I can count five or six. How’s that possible? First there was a flood of liquor stores. Then there was a backlash against the liquor stores. Then came a flood of crack houses. Now it’s a flood of medical marijuana stores. There has to be policy involved, because you wouldn’t be able to do it otherwise. I don’t know what those policies are. All I’m saying is what I see. Every fast-food restaurant takes EBTcards: Electronic Bank Transfer, which means food stamps. Jack in the Box takes it, McDonald’s takes it, Taco Bell takes it. When did that start? It wasn’t there in the 1970s. You got food stamps and you bought groceries. When did the policy change to allow them to create this blanket of people who can use their state money for Jack in the Box? The rise of obesity, the rise of diabetes in the hood – someone had to change a law in order to let these companies do it. We don’t know what it is, but it has to be.

HILL: It’s changing people and communities?

BRADFORD: Of course. It’s changing people. It’s destroying people. Same thing with gentrification: someone has to deregulate something to allow certain things that transform whole neighbourhoods.

HILL: It’s like in your Sexy Cash Wall mural, where you explore how lenders come into distressed communities and offer money for homes and how that can lead to urban blight or eventually wealth lost through gentrification.

BRADFORD: Absolutely. I can see it at the policy level and at the street level. I can see it on both.

HILL: In ‘Scorched Earth’ you show transformation caused by AIDS at the cellular, community and global levels. No wonder that your work has often been called brilliant. What year was it that you were awarded the MacArthur Fellowship – aka the Genius Grant?

BRADFORD: Oh girl, I’ve spent that money. It had to have been more than five years ago. Six maybe seven years ago? Maybe 2009.

HILL: Six years later, First Lady Michelle Obama awards you the Medal of Arts. You have the State Department’s Medal of Arts, a MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’ – we knew you were a genius, but now so does MacArthur – and with the Venice Biennale 2017, the whole world knows. It’s a singular honour to represent the United States in this renowned international art exhibition. You said you knew early on in your life you were powerful. Could you have predicted this?

BRADFORD: I never think about stuff like that. If I did think about the Biennale for five minutes, it was because I didn’t want to disappoint the people who believed in me, so I let them go ahead and put this little packet together because I didn’t want to disappoint them. But I didn’t think that I was going to be important. No. I didn’t think that I would be a runner in that. I don’t even think I thought about it. I certainly didn’t do any politicking. I certainly didn’t do any networking. It does seem to be a much watched thing and a huge platform, maybe because this country at the moment has had so much unrest around it.

HILL: You have five salons at the Biennale?

BRADFORD: In the first salon is Spoiled Foot.

HILL: I’ve read the poem that’s in the catalogue. You draw on Greek myth for this salon.

BRADFORD: Yes, Hephaestus is being cast out of heaven. One story is that his mother threw him out because of a deformed foot and another story is that actually Hephaestus was trying to defend his mother, Hera, and his father, Zeus, threw him over the cliff. That’s why I say it wasn’t my mother’s hand that was dragging me to the cliff. He wanders. He wanders on the periphery. It really is autobiographical. I did maybe have a spoiled foot that others could see, but I certainly couldn’t see it. People, my goodness, they sure did point at it a lot and talk about it a lot! I wandered. I saw a lot of interesting things. You know, Anita, I’ve been in and out of a whole lot of stuff and no matter what I was in, I always knew when it wasn’t my thing. But I was young. I will say, young, with a cute little face and low self-esteem, will take you a lot of places. I was definitely getting in cars right about then. I was an explorer. I was taking it all in and sometimes it was strange. That’s what that salon is about. I suppose it’s the feeling of a collapsed empire, like after hurricane Katrina.

HILL: You were commissioned to do a public artwork in New Orleans after Katrina.

BRADFORD: What you saw so much of was that water had collapsed ceilings and they looked very much like these moulded, corroded ceilings [in the first salon]. I do feel that although our political system will move forward, what we understand as being a political system has changed irrevocably. It will be something, but it won’t be what it was. So it’s this idea of a collapse. We’re not in reformation yet. We’re not rebuilding anything. It’s collapsed. That first salon is about that.

HILL: You want it to be very tactile.

BRADFORD: I want it to be tactile and I want to push the viewer to the edges of the room so they have to walk around it. You cannot enter into the centre at all. It’s tactile and physical and these things, these growths – you don’t know if it’s a growth or if it’s a hole or it’s a bullet hole or something, but it’s very tactile, very physical – they occupy the whole room. When I was very young I used to be fascinated by voices that occupied the whole room. That there was clearly distress on other people’s faces didn’t matter. I was always fascinated by that: how power flexes out. I would always only look at the people on the fringes in distress and then I would get angry at the centre because I felt like they should be kinder and a little more altruistic.

HILL: In the second salon, you go back to a familiar space.

BRADFORD: You come into the second salon and, for me, it really is the hair salon. It’s me hiding underneath Medusa’s crown and her hair. As I watched her turn her man to stone, there was fierceness – a fierceness that made me feel completely protected. There was fierceness in my mom’s customers. The women hid me.

HILL: Do you think that many of these women thought of themselves as Medusa? People who had been abused, who had been rejected?

BRADFORD: That’s interesting. I tell you what I got from my mother: my mom was confident enough that if a man got in her way, she could turn him to stone. I watched her turn many men to stone who got in her way. If they left my mother to her own devices, it was fine, but if they tried to get in her way, she’d turn them to stone. That beauty shop for me was a safe space.

HILL: That feeling of being shielded shows up in the poem ‘Spoiled Foot’. And the calm of the beauty shop shows in the paintings in the second salon. But then, as represented in the middle room, you began to wander.

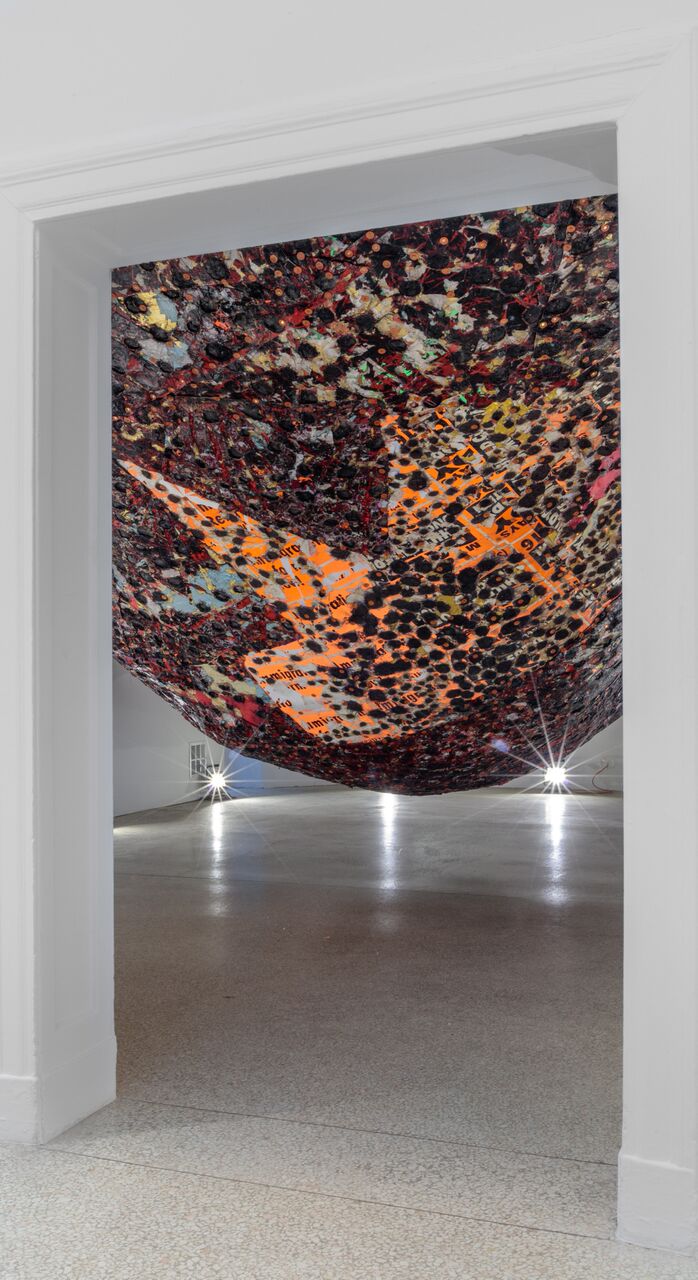

Mark Bradford,

Spoiled Foot

, 2016, mixed media on canvas, lumber, luan sheeting and drywall, dimensions variable, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2017

Mark Bradford,

Spoiled Foot

, 2016, mixed media on canvas, lumber, luan sheeting and drywall, dimensions variable, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2017

BRADFORD: Yes, this little boy remembers. The middle room for me is the Middle Passage and it’s really about something rushing in. I call it ‘Trouble Man’, after Marvin Gaye. There’s a song about ‘Trouble man’. He steals me out to sea: Middle Passage. In the belly of the boat, what were they thinking? People were kidnapped fast and would go from their village to the boat in very little time. We think of it as this long period of time, but often times, it wasn’t. Then they were lying in vomit in the bottom of the belly of a boat as cargo.

HILL: What about your own Middle Passage?

BRADFORD: I’ve often said that when you’re with your own – when you’re both black – you don’t call each other black. I was always aware of my difference, but I wasn’t gay or different when it was me and my own. When it’s black and white, you’re aware of race. For me, I was aware of race and I was aware that I was black. I was aware that I’d become this exotic thing. This exotic animal, almost.

HILL: Transracial?

BRADFORD: I wasn’t trans. I was Iman – Grace Jones kind of thing. I was racialized and exoticized. That was the Middle Passage for me. Those were the European years. That was me being an exotic thing, which is exactly what people would describe me as, an exotic thing. Jesus! I was in between being in Europe and being objectified and then running back here and dealing with AIDS and crack. No, those were not good years.

HILL: But the fourth salon seems to mark a turning point, flowing from the years of wandering.

BRADFORD: Yes. After this mental work is the muscular work. The painting where I knew who I was. I had survived – a little bit battle-scarred, but I’d survived. In the exhibition, you go from the Middle Passage to the next salon of three paintings that are muscular and about Abstract Expressionism and social abstraction. There’s a joy and a mastery and a power in those works. That’s me. That’s me as I knew I could be when I was seven years old. I kept it really quiet, but I knew that I could do that. The last room is really about me again, walking the earth. It’s not me walking literally. I don’t walk like that. But it is about me, as I am, vulnerable, in a vulnerable body, walking the earth with the potential for violence that will never leave me, but with a strength and also a back story. It goes in this way that I didn’t think it was going to. I think it’s probably the best thing I’ve ever done. I’ve never been as excited about a body of work.

HILL: I can’t even imagine a seven-year-old saying, ‘I’m going to be a great master painter of the twenty-first century.’ But you’ve done it with this combination of honours. It’s a huge platform.

BRADFORD: Anita, I’m going to tell you the truth. I’ve been hearing stuff like that my whole life. I’ve always tried to do what I do because, girl, there are so many boats that sweep you out to sea. I’ve always stayed centred. Six foot eight at fifteen, people said, ‘Now, you know you got to play basketball’ or ‘You know you got to go model’ or ‘You know you got to do this.’ I said, ‘All these big words, these big capitals around everything in my life … I’m going to just keep staying the course.’ Medal of Arts – I stayed the course. MacArthur – I stayed the course. Biennale – I stay the course. None of that stuff really gets inside.

Mark Bradford,

Medusa

, 2005, acrylic paint, paper, rope and caulk, Leucosia, 2016 mixed media on canvas, 259 x 366 cm, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2017.

Mark Bradford,

Medusa

, 2005, acrylic paint, paper, rope and caulk, Leucosia, 2016 mixed media on canvas, 259 x 366 cm, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2017.

HILL: Is that key to your continuing to be creative?

BRADFORD: I’m still the same boy walking the earth with the same wonderment and the same heartache and the same ... Honey, I wear it on my sleeve. I was like that at seven.

HILL: Let me ask you about materials and process. I’m going to start with scale, because you want to be that powerful figure in the room and your art is that powerful figure in the room. You move from materials like endpapers, these small papers, to paper bulletins that appear throughout a community. And now you’re producing your waterfall with huge, fibrous materials and that require a muscular process. How do you explain that? What can you say about that movement from working with these very delicate objects to mastering something that large and dense, each with its own power?

BRADFORD: If you work with something long enough, you’ll reveal yourself in it. I think that instinctively – I don’t care what anybody says – we hide. Point blank. I don’t care if you’re on Tinder, Grindr, whatever. You ain’t telling nothing. You’re telling the story that you’ve told a thousand times. It takes a long time to reveal yourself. When I’m working, I understand that. It’s a lifelong process and I’ll be peeling back the onion skins until I die.

HILL: Do you think of yourself as a painter, as a sculptor, as a videographer?

BRADFORD: An artist. In a long tradition of artists. It goes all the way back to the beginning of time. I’m an artist. I’m not a social activist. I’m not anything. I’m an artist with a small a. I’m peeling back the onion, surprising myself. Anita, I think I’m a real deep onion. Oh my lord. I’m in it now. I’m a little bit more than the surface and most of the time, I’m not happy with what I peel back. Can you believe that? I wish it wasn’t so revealing. I look at my work and I go, ‘Bradford, it looks like you, but are you going to put that out there?’

HILL: Does the fact that your work is abstract give you more protection?

BRADFORD: No. I think I could lie better through figuration. I could lie better with more props. The pure rawness of abstraction, it comes out the way it comes out. A lot of the things I’m working on right now seem dark and intense. It is me but I don’t want people to be thinking that about me. I can’t help it.

HILL: The words that you use in your art have evolved from phrases like ‘sexy cash’ to the Preamble to the US Constitution, including your large-scale work We The People (2017) for the US Embassy in London. Do you see parallels between the Sexy Cash text and the Preamble?

BRADFORD: Sexy Cash is about a whole mindset of exploitation and colonization. When I’m dealing with the Constitution, it’s this huge, unwieldy, heavy document and I’m trying to dismantle it, even though it will never be dismantled. I’m grappling with it. It’s me going to the Lincoln Monument and trying to rub out something. It’s me trying to grapple with the enormous history that made this country. It’s me grappling with being three-fifths of a man originally in this country in the south. Where do I fit into this document that was made when they weren’t thinking about black bodies? They were thinking about black bodies, but not as humans with rights. For me, it’s personal and emotional. It’s policy and personal and, somehow, the personal and the policy lock together and it makes it work. I’m trying to navigate through it. I’m trying to find out how I feel about policy. When I see a young black man murdered by the police on television, I’m trying to grapple with policy. I’m trying to grapple with it personally.

HILL: It seems that one of the ways you’re grappling with the policy and the personal is through your foundation Art + Practice, in the same building that housed your mom’s beauty shop.

Mark Bradford, Art + Practice, 2017, photographic documentation, Los Angeles, 2017. Picture credit: artwork © Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford, Art + Practice, 2017, photographic documentation, Los Angeles, 2017. Picture credit: artwork © Mark Bradford

BRADFORD: Leimert Park. When we got to Leimert in the early 1990s, it was a thriving black community with a lot of black businesses. It was really a black business mecca. Interestingly enough, it was turning from a merchant culture to a centre for Afrocentric arts and there was a push to get all the hair salons out of Leimert Park.

HILL: Were you a part of the Leimert arts community?

BRADFORD: It was odd. I was trying to be an artist, thinking of myself as an artist, but I wasn’t doing anything that looked like what was being sold in the shops. I wasn’t thinking about anything romantic or harking back to Africa or Kente cloth or anything like that.

HILL: Later you would come back and have a studio in Leimert. How did you and your partner Allan [DiCastro] come up with the idea for the Art + Practice Foundation in Leimert Park?

BRADFORD: We decided to move out of the studio and started thinking about a foundation. Allan has always been a social activist, always interested in policy as well. I watched him for fifteen years getting all the old black ladies in the community to go to vote. Allan was always working on community issues for no pay. When we decided to do a foundation, I only had the art side, but he said, ‘No, you have to do something with policy and social justice.’ Art + Practice came out of that. I think the gravitational pull to foster youth is because my mother was in care. I believe that often foster youth are born on the fringes of society, and through help, can move further into the centre.

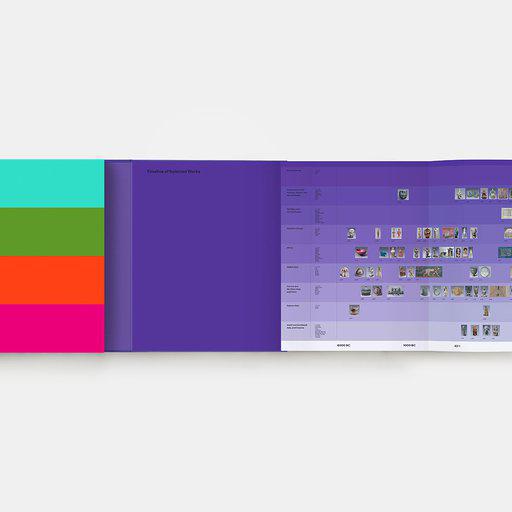

A spread from Mark Bradford's Contemporary Artist Series book, published by Phaidon

A spread from Mark Bradford's Contemporary Artist Series book, published by Phaidon

HILL: How would you describe the Foundation’s work?

BRADFORD: The Foundation supports both contemporary art and social services for foster youth. We have two arms. We collaborate with museums and we collaborate with a foster youth organization. It’s about policy – education, grades, housing. Some may be undocumented immigrants. It means helping them get a little job and then a little bit bigger job and then cleaning up their tax or credit records. I can tell them that I’ve been through all of that.

HILL: Right. The foster youth you work with are particularly vulnerable because they’ve aged out of the foster-care system so that the safety net they once had, even that little safety net, no longer exists for them.

BRADFORD: In that situation, you’re truly on your own on the fringe. So much of what I had to do, they have to do. They beat themselves up. I can say to them, ‘Stop all that. I’ve done all that. You can choose how far you want to go.’ That’s why I’m a strong proponent of education and why I love to see seventeen-year-olds on college campuses. It gives you at least a safe space to grow up. Education, housing, job training, job placement: these are fundamental blocks, and once we get all that, we can talk about maybe going to college.

HILL: A component of your contribution to the Biennale is your work with women in prison in Venice. What do you bring from your foundation work and your art to these women?

BRADFORD: It’s a collective and there are six different collectives throughout Italy. They’re basically a cottage industry – women making goods and selling them. They learn to show up on time, balance the books and interface with the clients. These are building blocks of education. It’s not enough. They need more visibility and more money. They also need a profile in the city. They need a store in the city.

A spread from Mark Bradford's Contemporary Artist Series book, published by Phaidon

A spread from Mark Bradford's Contemporary Artist Series book, published by Phaidon

HILL: Do you think of these women as the ‘fringe’, as you say?

BRADFORD: Absolutely. When I first met them, their eyes were always down. I did a talk and I brought pictures, all the way back from the boarding house, and all of my story, and by the end of it they were like, ‘We know you.’ Then it changed. I have a six-year commitment. We have a store, so when women get out of prison, they can work in the store and don’t have to leave the country. They have work and also have ownership. They share in the proceeds. They put the money back into the collective. They hire more people. Some are Italian, some refugees, some gypsies and some undocumented immigrants. A lot are Africans, and they all have this feeling that they’re bad women.

HILL: They’re the Medusas?

BRADFORD: Yes, that’s true. Full of rage. I say, ‘No. You’ve maybe done some things that you aren’t proud of, but hold your head up.’ As a representative of the United States, I wanted to introduce the women to other people in the art world who could support their programmes and to designers who can help them get better at the sewing. I wanted to connect the women prisoners to power and to money. That’s the project for me. For some people, living on the fringe is such a romantic thing. There are those who really are from the centre, but who run to the fringe so they can experience a kind of angst. But there are a lot of people who exist on the fringes of culture and the fringes of society and the fringes of the economy who don’t want to be there. They don’t know how to change: men with prison records, women with records, dyslexic people who can’t spell.

HILL: Would that include your foster youth?

BRADFORD: Right. If we can provide a non-judgemental site where they can feel safe enough to really express to you who they are, let’s go.

HILL: I have this picture of you, taken at some point in your childhood. You’re clearly creating something. Tell me what was going on with you at that time.

BRADFORD: I was about eleven years old. I was in our apartment in Santa Monica and my mom had bought me a potter’s wheel. I’d sit at that potter’s wheel for days and days and days. I have the same look on my face now when I work. I was a very delicate, sensitive child. I realized that there were a lot of things in the world that were going to really fuck with a little boy like me.

A spread from Mark Bradford's Contemporary Artist Series book, published by Phaidon

A spread from Mark Bradford's Contemporary Artist Series book, published by Phaidon

HILL: How did you ...

BRADFORD: Deal with it? I learned to run really fast. I think I had to emotionally move on because physically I looked the way I looked. I was other and I wasn’t protected by the pack.

HILL: Do you ever feel scared now?

BRADFORD: No. Not at all. No. In the art world I don’t feel like that. The art world is a safe place with safe ideas.

HILL: It seems to me that so many of the things that you’re accomplishing are making the world safer for people.

BRADFORD: Yes. Yes. Yes. I never thought about it until you said it, but yes, you’re right. I do want to make it safer. I do want to make these little safe spaces where it’s: ‘We’re going to work in this little safe space and figure out how to get some armour on you.’ Yes. I think everybody should have a little protection. I think everybody should have a little cover, everybody should have a little bit of a net and I think that society should give it to us, but for so many people society doesn’t do that. You have to build that net for yourself by any means necessary.

Mark Bradford, the Phaidon Contemporary Artist Series monograph

Mark Bradford, the Phaidon Contemporary Artist Series monograph

HILL: Do you ever sit still?

BRADFORD: Every night. I don’t work past about six.

HILL: Where does your mind go when you sit still?

BRADFORD: My mind doesn’t go anywhere. My mind is like the airport. Airplanes are like ideas. They land, they fuel and they take off. I read.

HILL: I’ve seen your library. You read everything and I see it in your art, the ideas that you began to study at CalArts have exploded.

BRADFORD: They take off. I don’t keep too much around in my head. I never have really. That’s why I’m here. I have an incredible focus wherever I am. I’m 100 percent there. Then in two hours, I’ll be at In and Out Burger, and a lady has just ordered and I’ll look at her hair and look at her shoes and look again. And the only thing I’m ever interested in is what I’m working on right now. I can’t go back and do something. I can’t remake it. I’ll say ‘I’m going to go back and make five of these. I’m going to make so much money.’ I never do. I’m living in my power, but as I’m living in my power, I’m constantly pointing to the fringes of society and saying, ‘There are people hurting. We can do more. We can do more. We can open our mouths when we know something’s not right.’

HILL: You can do art.

BRADFORD: I can do art. That’s what I do. That’s the whole thing.