There aren’t many contemporary photographers who intersperse their Instagram posts with carefully worded criticisms of the recent, disputed elections in Belarus. Fewer still divert funds and attention from their fine-art career to fund a wide array of projects, from a pro-EU campaign in the United Kingdom, through to his recent fund-raising drive to aid beleaguered clubs and nightlife venues across the world affected by the Covid-19 pandemic.

This is just one of the ways in which the German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans sets himself apart. As the New Yorker ’s Emily Witt put in a recent profile, the photographer “has explored the fragility of the political consensus on which his personal utopia depends,” with his images of nightclubs, kissing couples and warehouse apartment windowsills interspersed with astronomical photographs, car-headlamp shots, and ephemeral, almost overlooked snatches of uncommon beauty.

In this interview, published in Phaidon’s expanded and revised Contemporary Artist Series monograph on Tillmans , he discusses his life and work with fellow artist Peter Halley. Read on to discover how an early appreciation for record sleeves, clubs, magazines and image-making developed into a stellar career.

Love (Hands in Air)

, 1989 by Wolfgang Tillmans

Love (Hands in Air)

, 1989 by Wolfgang Tillmans

PETER HALLEY

: Let me ask you about the very beginnings of your work. Were you taking photographs from an early age?

WOLFGANG TILLMANS

: No, I was never particularly interested in my own photography until I was twenty. I never had the idea that I needed to record anything as a souvenir, and never dreamed of being a photographer. I always felt that the intention to record something, to remember something, stood in the way of experiencing the thing in the first place. When I was growing up my parents would avidly photograph and film on Super-8 all our family events and holidays. Maybe because of that family thing, I never needed it; for me it was just an experimental tool. Nobody told me it could be a valid art medium. I always had a thing for newspaper photos though. As a teenager I had a scrapbook into which I collected news photos, like the hijacked plane in Mogadishu or the suicide cult in Jonestown, Guyana. I felt drawn to how so much drama can be condensed into a cheap, grainy picture.

HALLEY:

You didn’t take any photographs at all as a teenager?

TILLMANS:

None, except for some home sessions of my best school friends Lutz and Alex and myself dressing up as New Romantics, pretending to be at London’s Heaven nightclub, whilst actually being in my parents’ living room. Then I took a couple of rolls on holiday in 1985 and 1986 when I was sixteen or seventeen. I borrowed my mother’s simple viewfinder camera, and on both trips I took a few pictures that are still relevant to me today. There’s a photo that’s sort of my picture number one (

Lacanau [self]

, 1986). It’s a self-portrait on the beach in France, photographing down on myself. It’s a pink shape, which is my T-shirt, and then a bit of black, which is my shorts, and then a bit of skin, which is my knee, and then a big space of sand. It’s also my first abstract picture: you can’t make out what it is, but it’s actually totally concrete at the same time. And it was about this moment of reaffirmation, or self-affirmation—I am. It was like coming out to myself as an artist. It’s a record of an experience I had. Once I’d experienced something, recognized something, I could take a picture of it.

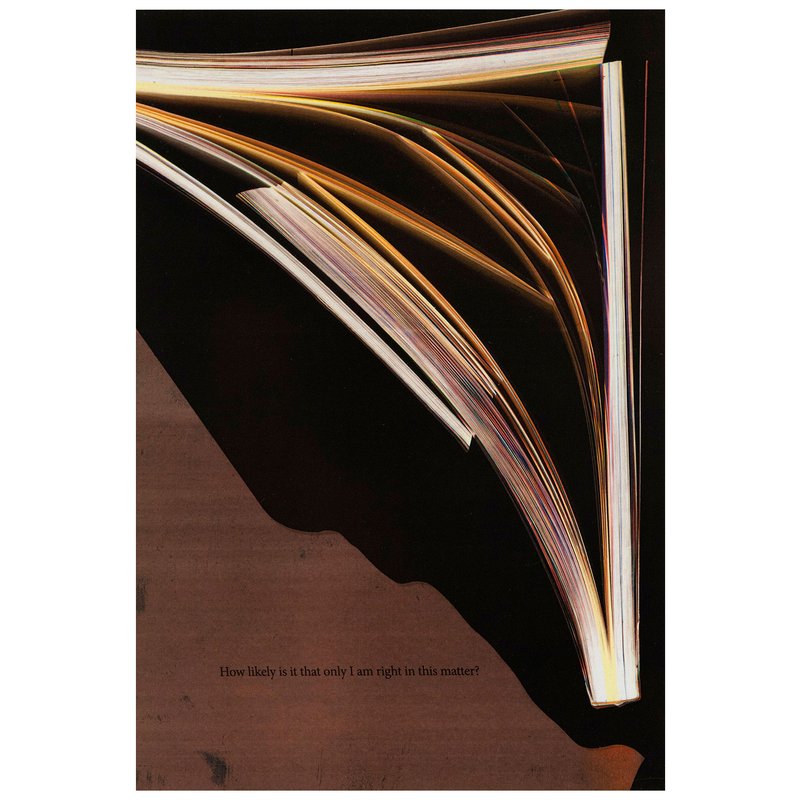

How Likely Is it, 2019 by Wolfgang Tillmans

How Likely Is it, 2019 by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

Did other people think of you as an artist?

TILLMANS:

No, not at that point. I didn’t have that image at all, because I couldn’t draw and I was bad at art in school. I was never brought up with the idea that I could be an artist, that I should be an artist, or that it’s a good job. The funny thing was that, even though I acted like an artist, it took me a long time... I don’t know when I really, fully adopted the idea that I was an artist. There was this weird schism in me: I thought and acted and behaved like an artist and yet when I was asked: "What do you do? What do you want to be?" I couldn’t say it. Even in Hamburg, after school, when I did community service, I was writing applications to do an apprenticeship in business administration or in an advertising agency because that was what I thought I should do.

Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees

, 1992, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees

, 1992, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

Be sensible?

TILLMANS:

Sensible, yes. I never actually mailed them, however.

HALLEY:

You finished high school in 1987?

TILLMANS:

Yes, that was in Remscheid where I was born and grew up, a manufacturing town specializing in hardware—hammers and pliers and so on. Everybody there was involved in making tools. My parents ran a small business exporting tools to South America. I couldn’t wait to leave after school to live in a bigger city, so I moved to Hamburg to do community service instead of military service, because there was still the draft in Germany.

HALLEY:

Before you went to art school?

TILLMANS

: Yes. You usually go into the army straight after school to get it out of the way.

HALLEY:

So you chose community service. Did you have to be a pacifist?

TILLMANS:

Yes, you have to be a conscientious objector, and then you have to do twenty months of community service, but you can choose where, and what you want to do. So the logic for me was that it would be in the biggest German city where I could do it—which was Hamburg, because Berlin was not yet part of West Germany. For the first ten months I worked for a mobile social health service, helping nurses wash patients, doing cleaning for old or disabled people living at home, doing light medical and social work in old people’s homes.

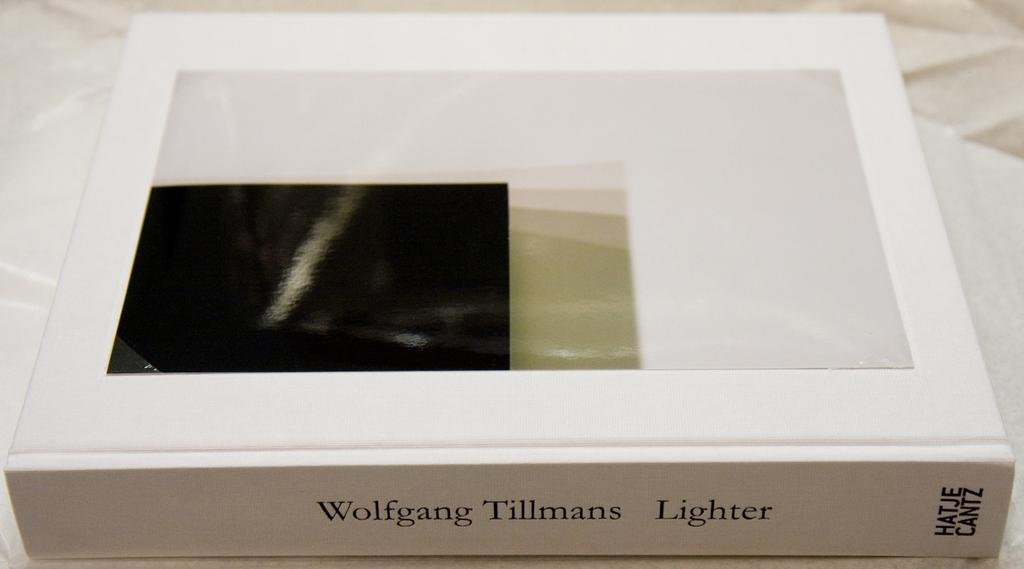

Lighter , 2007 by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

What about the last ten months?

TILLMANS:

Then I had a bad back, and was also tired of my boss and the whole situation. So I claimed that I couldn’t do it any more and got transferred to operate the switchboard of another help organization in the centre of Hamburg. From there I organized my first exhibition. Being on the switchboard, I could use the phone all day, and the photocopier in my office.

HALLEY:

What kind of things were you making?

TILLMANS:

In my last year in high school I discovered a Canon laser photocopier in my local copy shop, which was the first digital black-and-white photocopier that could really reproduce quality photographs at that time. You could enlarge them up to 400 percent. Then, when I lived in Hamburg, I approached this nice gay café to see if I could do an exhibition of these photocopies there.

HALLEY:

None of them were your photographs?

TILLMANS:

A few of them were, but others were taken from newspapers. I didn’t even own a camera then. I was zooming into photographs, destroying, dissolving their surfaces. They were displayed as triptychs of three A3-sized photocopies. I felt very strongly that was what I wanted to do, so I put on this exhibition, which even got a couple of sales and the attention of a curator, Denis Brudna, who gave me a bigger exhibition in 1988. I was totally driven, without categorizing what I was doing.

Concorde L432-9 , 1997, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

You were driven to try to find venues so you could show it to other people?

TILLMANS

: Yes, exactly. These photocopies, these triptychs made sense to me in my bedroom, in my flat in Hamburg, and I felt they should be seen.

HALLEY:

But you felt they should be seen in a ‘zine that you’d produced or in a café rather than a Kunsthalle or a gallery?

TILLMANS:

That was primarily because I wouldn’t have dared at that point—even though I sent everybody invitations!

HALLEY:

What art were you looking at during this period?

TILLMANS:

There was one exhibition in Hamburg at the time that left a lasting impression on me: the "D&S" exhibition. It had people like

General Idea

, David Robbins, his

Talent

portraits of artists (1986), and also Alan Belcher and

Jeff Koons

, that whole generation.

HALLEY:

Basically that’s my generation.

Talent

is such a great piece, and people still remember it. And Alan Belcher is really interesting. Do you know him?

TILLMANS:

Yes, because he lived in Cologne in the early 1990s, so I met him there a few years later. He showed with Daniel Buchholz then.

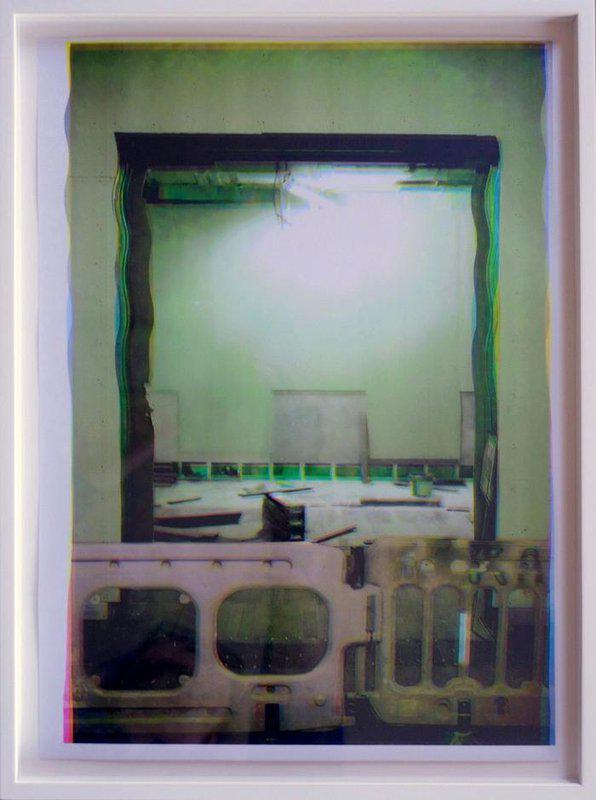

Freischwimmer

190, 2011, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Freischwimmer

190, 2011, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

He was the other partner at Nature Morte with Peter Nagy. What else were you looking at?

TILLMANS:

I also very much liked

Jenny Holzer

. I bought a complete set of prints of the Truisms for 120 DM with money saved from my community service. I really loved that piece, and I also liked

Barbara Kruger

and

Laurie Anderson

. They all touched me in terms of how it’s possible to pursue your work and at the same time aim to reach a broad audience. Unfortunately they’re not the coolest people to mention now.

HALLEY:

I think that’s only temporary.

TILLMANS:

Yeah. A lot of that work really moved me on a very direct level, but at the same time it was conceptual, some of it. It still had the power to touch me; that’s also what I always liked about

Andy Warhol

’s work. It didn’t come with an explanation as to why a grainy picture of a flower should affect you the way that it did.

Freischwimmer TFL 150

, 2013, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Freischwimmer TFL 150

, 2013, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

What about

Richard Prince

?

TILLMANS:

I was aware of him. There was a great cover of

Wolkenkratzer

magazine with his appropriation of the picture of that child actress, Brooke Shields. That really spoke to me. After that I subscribed to that magazine; suddenly I felt I wasn’t alone. At the time I didn’t know any artists or anything.

HALLEY:

Did you look at any well-known historical photography?

TILLMANS:

No. Classic photography seemed so remote, so irrelevant to me. It just didn’t touch me. Now I’m glad I never knew the history of photography until after I found my stylistic footing. However, photos on record sleeves—Peter Saville’s New Order covers and the photography in

i-D

magazine—touched me in the most profound way.

Freischwimmer 78

, 2004, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Freischwimmer 78

, 2004, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

Can you tell me what

i-D

meant to you? What was

i-D

culturally? Why was it such an attraction?

TILLMANS:

I think the main attraction was that it showed you that you can create your own identity, or rely on your own identity without having to subscribe to any official rules of how to behave and how to look in order to be right or to be cool. In particular, it was always beyond the commercial. It was all about being free, in terms of money. The sorts of lifestyles that were endorsed in

i-D

were all about their accessibility. And things were labelled with their prices, to show just how cheap things were, like second-hand coats for £5 and sunglasses for 99 pence. And so there was this liberty: you could actually be having a great time, be sort of glamorous, and at the same time not buy into any commercialism.

HALLEY:

I’m older and I missed that, but I can understand that pretty well.

TILLMANS:

With magazines and the whole club culture it just seemed so relevant, so tangible. In 1988 I started to go out tons and take ecstasy and that became this all-encompassing experience that I wanted to communicate to

i-D

—how exciting Hamburg was at the time. I bought a flash for $15 and took my camera and went to the clubs, and sent them to

i-D

. Those were the first pictures I ever took for a magazine, and they got published. That was the magazine I wanted to be in; there was no other magazine I wanted to move ‘up’ to, as most photographers do. I never had any interest in pursuing a career in fashion or advertising. After that, a local magazine called

Prinz

commissioned me to take club pictures. So it was this very immediate thing: I wanted to capture how amazing the scene was.

Installation view of Tillmans' exhibition at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2012

Installation view of Tillmans' exhibition at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2012

HALLEY:

It’s different in the U.S., but as I understand it, European club culture in the late 1980s had a kind of ethos. If you take it as a whole – your experiences, the people you’re with and the things you’re doing – do you see the whole thing as having a positive ethos, almost a purpose?

TILLMANS:

Absolutely. It definitely seemed to be for a better society, a better understanding. It was a utopian ideal of togetherness. That’s how living together could be: being peaceful together and enjoying the senses. It seemed a very tangible and inherently political thing to me. But that wasn’t fully accepted at first. Then in Europe it became common culture through acid house and techno music, and suddenly everybody felt that there was this utopia that was very real, and you could actually live this utopian dream. As usual, of course, it didn’t last.

HALLEY:

Do you think it had any relationship to the 1960s equivalent? Or did you feel it was a new thing?

TILLMANS:

No, that was the incredible thing. In 1988 when it started for me, for the first time in my life I felt part of something first hand that I wasn’t distant from, that wasn’t retro, that was just completely in the here and now. And there was absolutely no sense of yesterday because everything about it was completely new. That sound, the music of the time, was absolutely unheard of.

Podium

, 1999, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Podium

, 1999, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

The acid house scene and the humanitarian feeling and the communion with people whom you barely know, was that, coupled with group sexuality, an ideal that even went beyond hedonism?

TILLMANS:

It can be spiritual. I think that’s one of the strongest points of it: this idea of melting into one. Paradise is maybe when you dissolve your ego—a loss of self, being in a bundle of other bodies. It’s really the most regressive state you can be in on earth. The other way to it is sex. Neither of the two are ideal for permanent models for living. Clubbing and sex have great potential to go stale and become boring and repetitive.

HALLEY:

A number of your photographs lead to the melting and blending of bodies. It’s a big theme in your work.

TILLMANS:

Yes, definitely. That idea of being together, of fusion.

HALLEY:

What was the first gallery exhibition or relationship that moved your work into the right context, when your work began to be seen?

TILLMANS:

That was in January 1993 at Daniel Buchholz in Cologne. I’d been exhibiting since I was nineteen, and started publishing in magazines a couple of years after that, but somehow I consider that exhibition to be my first.

HALLEY:

How did you meet Daniel Buchholz? Was his your first major gallery?

TILLMANS:

Yes, it was. I had a loose contact with Maureen Paley in London, whom I saw when I was a student now and then. Then in the autumn of 1992 she decided to take a picture of mine to the Cologne unofficial art fair, the Unfair—a large inkjet print of

Lutz & Alex

, sitting in the trees. I decided to go to Cologne for that only because there was also an

i-D

party there the night before. I decided I might as well install the picture at the Unfair myself. The night before the art fair, at the

i-D

night, Michael Hengsberg [Daniel’s assistant at the time], told me they’d really like to do a show with me. They invited me on the strength of the work they’d seen in

i-D

.

Outer Ear

, 2012 by Wolfgang Tillmans

Outer Ear

, 2012 by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

At the time of that first show, who was encouraging you and talking about your work? How did people first interpret the work? What happened after that first show? Clearly it didn’t go unnoticed.

TILLMANS:

No. The main thing was that I found my signature in terms of showing my pictures in a non-hierarchical way. It was a very radical thing at the time, to show magazine pages alongside original photographs and to leave the photographs unframed; not to make a distinction in terms of value—you know, what belongs on the wall, what doesn’t. For me, the printed page had been a sort of unlimited multiple from the start. I always loved magazines and newspapers, as actual compositions and objects; since I was designing some of my spreads in

i-D

at that time (1992–93), they were as close to an original work by me as the print that I was making in the dark room. I think that was one key aspect that I got across. It came naturally at the time; I wasn’t calculating it in a cold way. I guess you’re never aware at the time that it might be something important; you only ever have a presentiment of it.

HALLEY:

So people didn’t just see it as a show of photographs, but also as an installation about information, or images of the world?

TILLMANS:

Yes, it was very much an installation. It was a tiny space: 3x3 meters, literally a white cube. One wall was very sparse, with a series of pictures in one straight line, the

Chemistry Squares

[1992]. Then, as it went around the room, it got denser, from floor to ceiling; there were structures of grids and lines involved. For some reason, already at the opening there was a special buzz, and there were lots and lots of people. It’s funny how later you hear who saw it, like

Kasper König

. I sold my first picture to the artist

Isa Genzken

, which was hugely exciting for me. At that time we immediately struck up a special relationship; that was a great encouragement; soon after that we started working together on the portfolio "Atelier." Also Daniel told me a week later that Sigmar Polke had spent a while looking at my show.

HALLEY:

Yes, this is what I’m trying to get at: that early moment when people who form opinion, whom you might value personally, begin to come into contact with your work.

TILLMANS:

Another important thing that greatly enriched my life was that after having lived in England for more than two years, I was able to come to my own culture in Germany as a semi-outsider, to participate as both part of and not part of the local situation. Cologne was then the centre of the German art world. I was part of that scene but at the same time living in London, where I was more connected to the music, magazine and nightlife of the early 1990s. For a while I was also connected to Paris, where I was in a number of exhibitions, most prominently "L’hiver de l’amour" [1994] at the ARC Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. It was a very open period—the bottom of the art market after the crash. It’s surprising how fluid things are during these ‘difficult’ periods. Also through an exhibition in Paris I got in touch with a Swiss workwear manufacturer, who invited me to photograph their clothes in actual working environments [

Operation theatre II-I

, 1994].

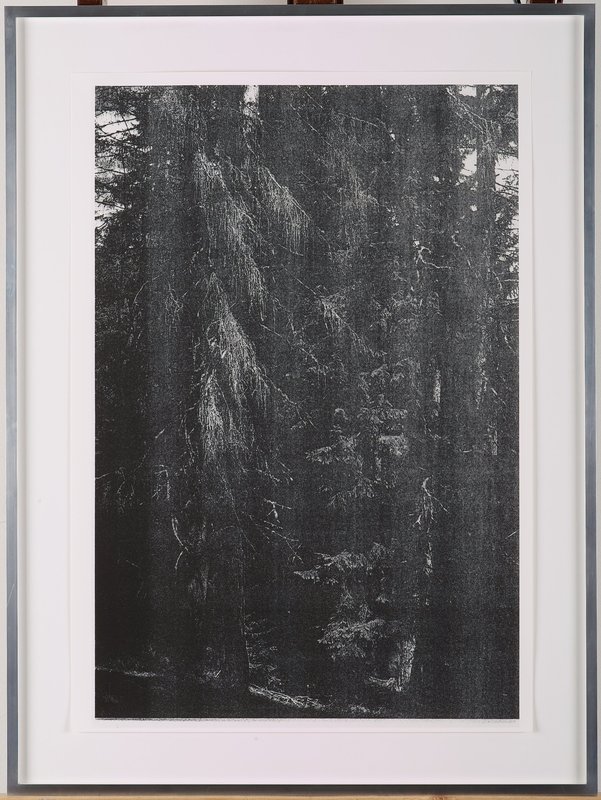

Wald (Briol I)

, 2008, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Wald (Briol I)

, 2008, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

Can you elaborate on what the artistic situation in Europe was like then?

TILLMANS:

In continental Europe there was this emerging scene of artists questioning the art object and the whole practice of exhibiting, and I think that’s why I was so well received there. They’d gone through the object-driven 1980s, and young artists were really not interested in that anymore; they were questioning why or how we exhibit at all and how objects can still be meaningful. My taking magazines seriously as a platform for my work as an artist came from that sense of urgency. The British scene hadn’t really had that wipe-out after the 1980s and was, with people like

Damien Hirst

, celebrating the object and production values. So there were different agendas in Britain and the rest of the art world. I remember in the summer of 1993 gallerists Gregorio Magnani and Daniel Buchholz invited a dozen artists and friends to a house in Tuscany with this idea that we would all spend time together to sit down and think about how things could progress, what art could look like in the future. It really was completely open, up for grabs. Nobody was selling anything, and there was a similar situation in New York and in Paris, where there were three independently published small art magazines, three circles of people at the magazines

Documents

,

Bloc Notes

, and

Purple Prose

, all asking the same question: how can meaningful art be made now? They all emerged in Paris at almost exactly the same time.

HALLEY:

Who were you in contact with at the time, in Cologne and in Paris?

TILLMANS:

People like Justus Köhncke, Isa Genzken, Lothar Hempel, Marcel Odenbach,

Carsten Höller

, Philip Parreno,

Dominique Gonzalez-Forster

,

Angela Bulloch

,

Maurizio Cattelan

, Lily van der Stokker and a little later Kai Althoff, Cosima von Bonin, Michael Krebber, and Christopher Müller.

HALLEY:

How would you describe your reception in the States?

TILLMANS:

In late 1993 I made a trip to New York and three different galleries were concretely interested in showing me, which at the time seemed extremely exciting. But on the other hand I was just... well, dealing with it. I wasn’t sitting there saying, "Incredible, three New York galleries want to show me!"

HALLEY:

It’s so anxiety-producing.

TILLMANS:

At the time it was like....

Lighter Green VI

, 2010, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Lighter Green VI

, 2010, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

"What if I choose the wrong one?"

TILLMANS:

Yes, but I was also quite confident in a way. Whatever happened to me, I never felt out of place, like, "I shouldn’t be here, this is vertigo-inducing."

HALLEY:

I think every artist who manages to reach the goal of success has to have a sense that they’re entitled to it; they have to internally believe that this is where they belong. Inside, we think we’re saying something important and in a way the recognition is more of an affirmation than a surprise. Do you agree?

TILLMANS:

Yes. It’s dangerous to say because it’s easily misunderstood as arrogance.

HALLEY:

It could be, but frankly I think being an artist and having something to say and

being confident about it isn’t arrogant. It’s a relatively modest goal.

TILLMANS:

Yes. Anyway, I joined Andrea Rosen’s gallery and after another visit decided to leave London and move to New York, where I arrived in September 1994, coinciding with my first one-man show there. Andrea’s gallery was an exciting place, with artists like

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

, Julia Scher,

John Currin

, and Sean Landers showing there, and it was impressive to experience the density of artists of all generations in downtown New York. Already during my first month there I met dozens of great people. I generally felt appreciated in a way that maybe only Americans can make you feel. And on a personal level I met the love of my life there, another German artist who had moved there around the same time as I did. He collaborated with artist Thomas Eggerer and was a member of Group Material; we had dramatically different practices yet similar overall concerns and interests, which was great.

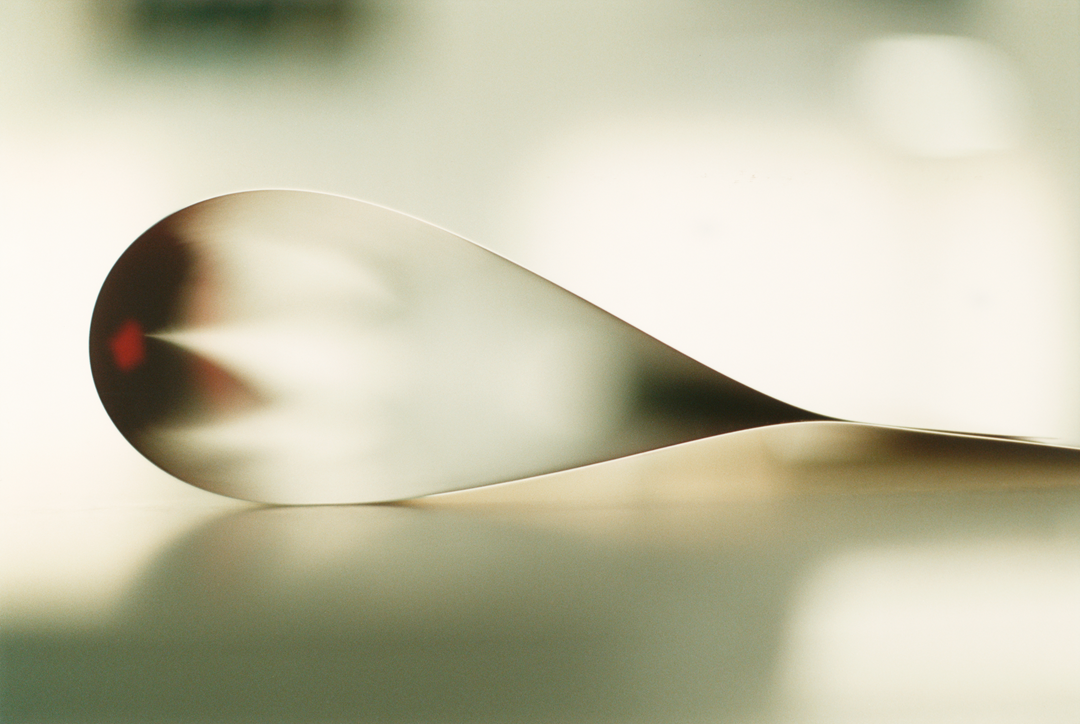

Paper Drop (Star)

, 2006, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Paper Drop (Star)

, 2006, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

At it’s best, New York can be just like that: bringing people together like no other place. To move on to themes in your work, for the most part the universe in your photographs seems luminous and joyous. But I’m wondering, if you were to identify any darker or more pessimistic emotions that might be in the photographs, what would they be?

TILLMANS:

All my work has been made with the knowledge of possible death, because since 1983 I’ve had an acute awareness that this disease, AIDS, affects me. In 1985, after my first few sexual encounters, when I was seventeen, I had this big AIDS fear. That’s actually crazy, when you think of a seventeen-year-old schoolboy lying in bed thinking he’s going to die.

HALLEY:

I don’t think it’s that crazy. It happened. It was real and a lot of people did get sick and die.

TILLMANS:

The threat of AIDS has been with me for all my active sexual life, and so all the celebration and the joy and the lightness in my work has always taken place with that reality on board.

HALLEY:

In other words, if life is fragile one needs to celebrate and appreciate it more?

TILLMANS:

Yes—well maybe that’s too much of a statement. You could take away the "if," because life is fragile, and you have to celebrate it and enjoy it and not despair over the fact that it’s fragile because it just is. And that’s why I don’t despair; that’s why I’m optimistic, because it doesn’t only affect me—it affects us all. It just brings us all together again in the sense that that’s part of the deal. We’re all equally mortal.

HALLEY:

You had your very own experience of tragedy in your life. How did that affect your work?

TILLMANS

: That’s the darkest period in my life, when Jochen died in the summer of 1997, practically out of the blue with one month’s warning. The pictures from that time, I never explicitly said what they were about.

Astro Crusto

, A, 2012 by Wolfgang Tillmans

Astro Crusto

, A, 2012 by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

Pictures of him?

TILLMANS:

No, for example

Untitled (La Gomera)

[1997] or pictures in Munich, some still lifes, our hands clutching on the day he died. There’s a self-portrait, when I’m starting to ask, "Why am I here?" There’s a still life of the food that we took on the plane from the last hotel night back to hospital. I’ve never explained this to anybody before, because I never want to bring my personal life into my work in a direct way. It should never be read as, "I’m telling you about my personal life, these are my friends, this is what happened," and so forth. I’ve never wanted to create this inclusion/exclusion as regards my private life.

HALLEY:

It’s nearly five years since Jochen died. How many years were you together?

TILLMANS:

Almost three. Which always sounds so brief, but it was the perfect match. We met in early ‘95 when we both lived in New York. In ‘96 we moved to London to live together. That’s where Jochen started painting again, and in that short period he created a group of paintings that posthumously got a lot of attention. We didn’t actually know he was sick until a month before he died. The work from that time, autumn 1996 to summer 1997, when I was working among other things on Concorde, was fuelled by a profound sense of happiness. We had for example a great time when we worked together in staging and preparing the Kate Moss pictures. I helped him find source material for his paintings. He introduced me to Spanish and Italian Baroque painting, and we discussed each other’s work almost daily. It all ended the day after the opening of ‘I didn’t inhale’ at the Chisenhale Gallery in London, for which we’d had a huge opening party at our place. Jochen came down with AIDS-related pneumonia from which he never recovered.

HALLEY:

That’s an enormous tragedy and burden. I remember when it happened, I thought you were able to go on in a very dignified way. I don’t want to pry into personal matters, but besides the enormity of him being gone, to go through that kind of mourning and loss is not something that typically happens when you’re only twenty-eight. How else did this relate to your photography? How did you manage to continue?

TILLMANS:

It completely took the steam out of me. I cancelled everything and I wasn’t really functioning.

HALLEY:

Were you able to take pictures?

TILLMANS:

I did carry on taking pictures. Not a great deal; a self-portrait, when I cleared out his studio.

HALLEY:

Those pictures are so beautiful. There’s a sense of peace, rather than anger.

TILLMANS:

I was very much overcome by the power of it all. I felt crushed, of course, but it felt so powerful that I couldn’t really rebel or complain. It was the biggest thing that ever happened to me and so I never felt anger because when something is so powerful, what can a little bit of anger do against it?

HALLEY:

If you don’t mind my saying so, I’m glad I asked you because now I clearly understand the ethical dimension of your life and work. Certainly death is one of the big ethical issues and for you to speak about the nature of your mourning, I think ties very much into your thoughts about how to form a photograph or an installation.

TILLMANS:

I can’t control everything in my life and the installations are a reflection of this underlying sentiment that’s been with me from an early age: this dichotomy between wanting to control everything and the humble acceptance of what actually is. I think this is, for example, reflected in the use of materials in my work, showing that there is no definite or permanent answer in photography. A photograph can never be stable and perfect and protected and I like the way it’s constantly in flux. I position the different angles that go on in the materiality of a photo and I point them against each other. Some pictures I have framed, and others I hang directly on the wall as inkjet prints, and then with others I take away the whole uniqueness and limited-edition-ness thing and give a magazine page or a postcard an equal presence on the wall.

Silver Installation VII

, 2009, 26 colour photographs, 306 x 843 cm, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2009

Silver Installation VII

, 2009, 26 colour photographs, 306 x 843 cm, installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2009

HALLEY:

You’ve given a great deal of thought over time to your exhibition practice, and the installations have continued to evolve dramatically. The way you hang pictures and the technical considerations given to the photograph as an object have all been important. Can you give an idea of how that has evolved over the last ten years?

TILLMANS:

What intrigues me is the tension of the two key qualities of a photograph: the promise of it being a perfect, controlled object, and the reality of a photographic image being mechanically quite unsophisticated. It creases or buckles when it’s too dry, curls in humidity, becomes rigid and vulnerable when it’s mounted, and for that reason, loses its flexibility. I choose to reconcile all this and don’t try to pretend that it isn’t happening. I’ve made all of that part of the beauty of the visual experience. The fact that photographs aren’t permanent is like a reminder of our condition; showing their vulnerability protects one from the disappointment of seeing them fade. The inkjet prints have this built in as a concept: their impermanence is clearly imaginable yet the owner also has the original master print and can reprint the inkjet print when they feel it’s necessary.

HALLEY:

How do you decide which images are framed under glass and which are pinned?

TILLMANS

:

I’d never pin a photograph, because when you pin it you pierce the corner. So I found this tape with which I can tape a picture to the wall without it even touching the surface of the emulsion, and I can remove the tape afterwards and the print is totally untouched. I pin the magazine pages with steel needles, because if you tape a magazine page, you can never safely remove the tape, it always tears. I use this made-up logic in terms of how I present the stuff, how I fix it to the walls. Somehow, however minuscule these technical decisions probably are in the larger picture, they’re crucial to the meaning of my project and what’s important to me—to really understanding the nature of the object that I put up. Each thing needs a different treatment. At the same time, of course, they use a language of personal associations and ‘thought-maps.’ Then again I also use grids and linear installations, hanging the works all around the gallery at the same height.

Tate Modern Edition

, 2016, by Wolfgang Tillmans

Tate Modern Edition

, 2016, by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

I like your description of the various methods of caretaking, or hanging your images. Basic themes in your work are spontaneity, being in the moment, and enjoyment. Combined with that, however, is a tremendous sense of concentration, and a strong impulse to take care of things in a very… you could almost use the word "loving" way that doesn’t abuse this poor photograph. Often, really good art combines contradictory sides of the artist’s psychology or ethos. Your description in this case brings that out for me. It might be that what you do is synthesize impulses that we may typically see as contradictory—make oil and water mix.

TILLMANS:

That’s a great way of putting it.

HALLEY:

What are you thinking about as you place photographs on the wall?

TILLMANS:

It comes largely from a very personal approach—things that are meaningful to me at this point, in that room or in that month. I usually spend about a week on an installation, which includes day and night shifts. I’ll work on it, then leave, then come back fresh, have a new angle on it, change the whole thing, and so on, until the installation settles into a shape that gives me the sense that I can’t add to it or change it; only then do I feel it’s finished. Underlying decisions regarding content there are, of course, formal decisions about colours, shapes, sizes and textures.

Wald (Briol III)

, 2003 by Wolfgang Tillmans

Wald (Briol III)

, 2003 by Wolfgang Tillmans

HALLEY:

It all seems very multi-determinal: various vectors of intuition about your own

interests, your perception of the audience, how you feel the photographs will form the space at any given time.

TILLMANS:

Exactly. "Multi-vectored" is the word I like to use. This way of hanging allows for each of these different vectors to have a voice, so that things are not exclusive. It’s an inclusive practice, which allows me to have a little joke in one corner and some sort of personal wink to somebody else in another corner. And also to say something very deliberate in terms of formal considerations related to, say, portraiture or landscape. It’s not all personal, although that is one level. The viewer should be encouraged to feel close to their own experiences of situations similar to those that I’ve presented to them in my work. They should enter my work through their own eyes, and their own lives—not through trying to piece together mine.

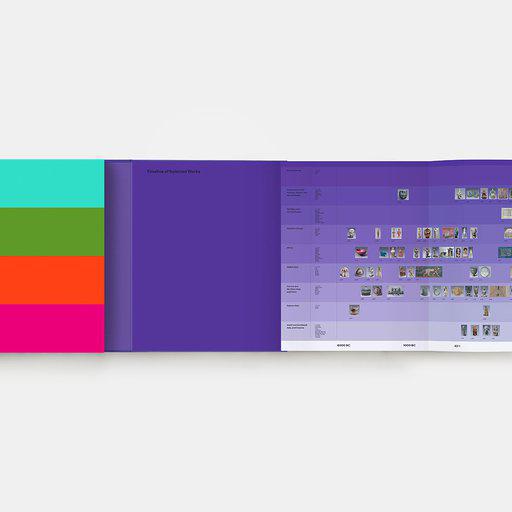

Wolfgang Tillmans' Phaidon Contemporary Artist Series monograph

Wolfgang Tillmans' Phaidon Contemporary Artist Series monograph