What is art? The question has puzzled philosophers, historians, artists, and audiences as far back as the ancient Greeks and remains a topic of debate today, as the definition of art continues to expand and shift. That there has been no consensus after more than two millennia is a testament to the complexity of the query and the subjective nature of its answer.

Traditional histories of art have aimed to answer the question by looking at artworks from various vantage points and classifying them by period, place, style, object, subject, material, or technique. Despite the diverse ways art has been interpreted (and appreciated) over the years, works are rarely considered in all these aspects at once, and no book has adequately represented the infinite connections that link works past and present. No book until now, that is.

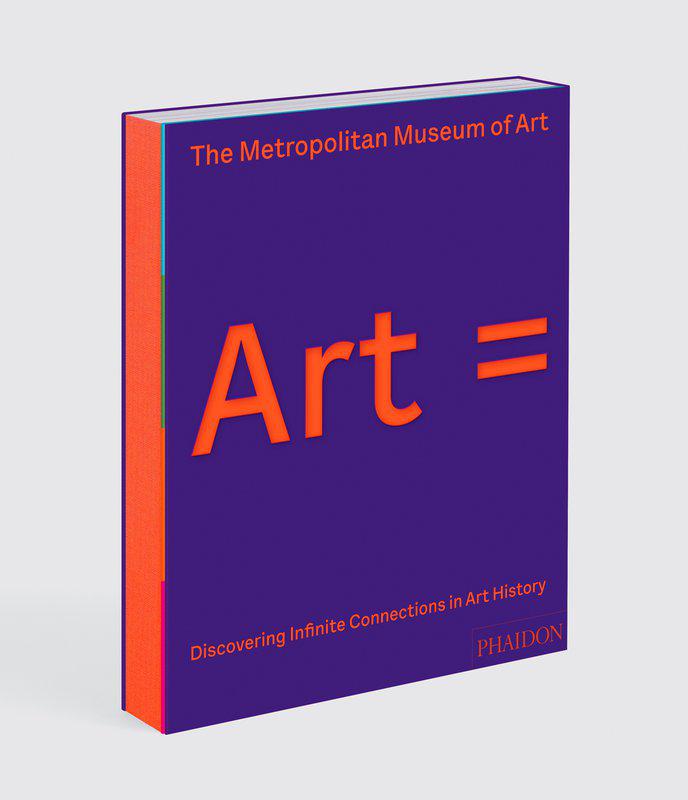

The Metropolitan Museum’s book Art = provides a new starting point, encouraging readers to make their own connections and draw their own conclusions. Featuring more than 800 artworks from the collection of The Met, this groundbreaking book — organized by thematic keywords — draws upon the museum's online Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History — offering fresh, unconventional ways of engaging with visual culture. We asked the Met's Director Max Hollein to tell us more about it.

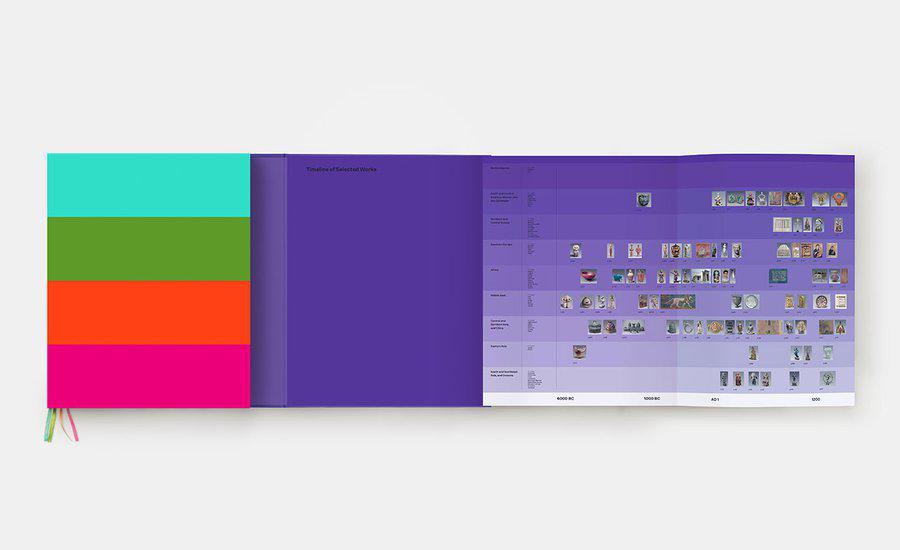

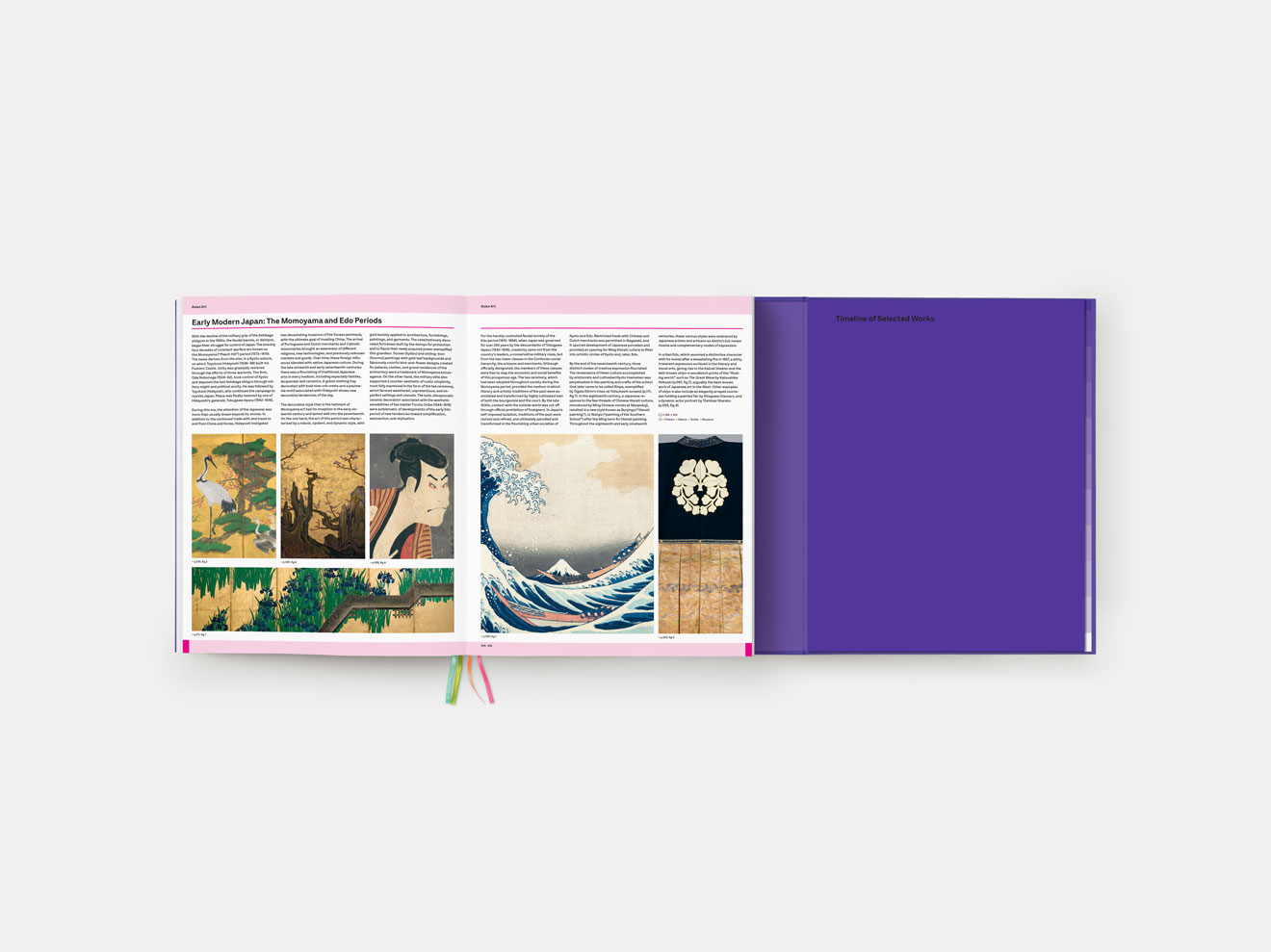

A spread from

Art =

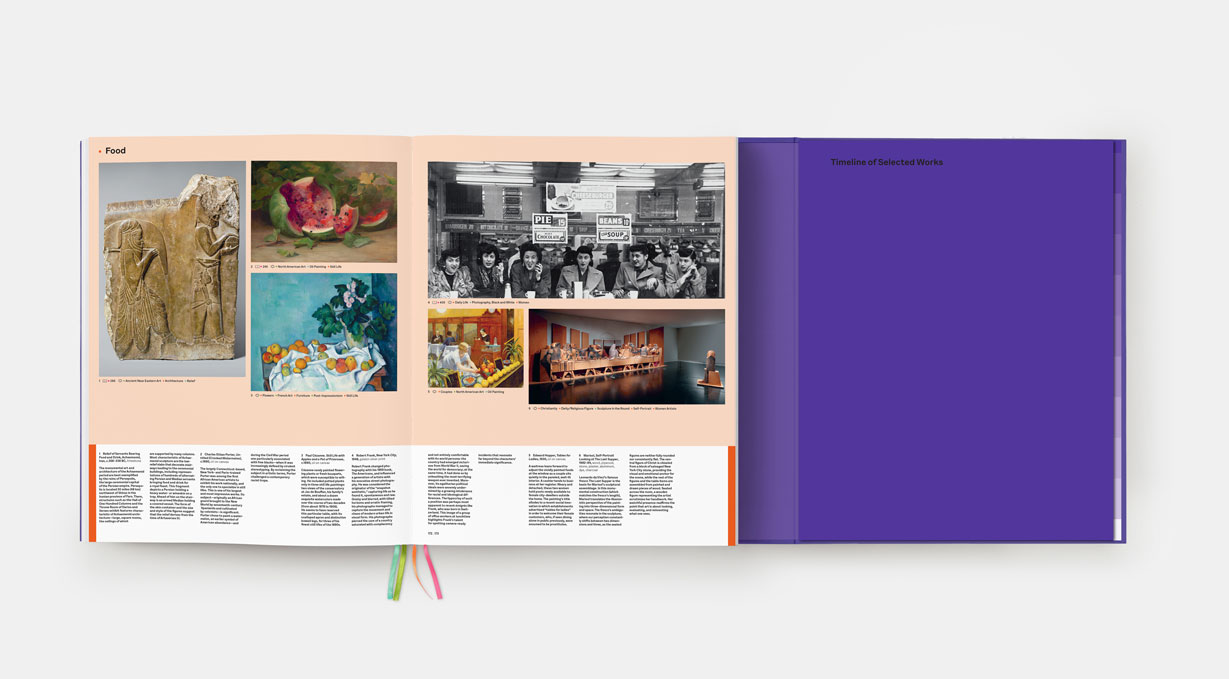

A spread from

Art =

Art history, and the perceived cultural values of one set of works when compared with another is always changing. How is Art = different from a book about art history that might have been published, 50, 15, or even five years ago? Art = organizes works of art in an entirely new manner. Unlike other books that cover the history of art, this publication doesn't present works in chapters that follow a linear chronology defined by period. Traditional books generally begin with cave paintings, move to the ancient Near East and Egypt, jump to Ancient Greece and Rome, and continue on that path through to the 21st century.

Alternatively, or additionally, these books rely on conceptions of artistic movements, styles, and periods that favor Western European art, such as "Medieval Art," "The Renaissance," and "The Age of Reason." Authors often merge regions with complex and varied cultures that fall outside the European mainstream under one broad heading, such as "African Art," Islamic Art," or "American Art," without providing any additional ways of looking at the work. Before Art =, wide-ranging publications on the history of art hadn't accounted for the many layered interpretations inherent in each work of art, or provided narratives showing how art objects connect across time and borders.

Of course, books such as E. H. Gombrich's The Story of Art and H. W. Janson's The History of Art, first published in the mid-twentieth century and still popular today in revised and expanded editions, continue to have their merits. That said, the Gombrich and Janson texts can pose a barrier to entry and limit individual exploration; the dense, continuous narrative of both books is daunting to many and establishes a "right" way of talking about art, thus putting off those who many interpret the work differently.

By contrast, Art = provides readers with multiple points of entry: its creative organization, its broad range of art and artists represented, its cross-cultural juxtapositions on keyword pages, and its pull-out reference timeline. Unlike other books in the genre, this publication doesn't claim to be the definitive authority on the narrative of art history. Instead, it provides evidence that appreciating and interpreting art is a personal and evolving process, and it encourages readers to make their own connections, to see works through many different lenses, and ultimately, to think creatively.

Perhaps one of the most innovative aspects of Art = when compared with other books about art history is the method of selection. Traditional books were written by art historians who compiled works of art, themes, and essays based on their scholarship, connoisseurship, and to some degree, their personal taste. Art = uses a more democratic approach, pulling from a whole range of curatorial voices and featuring the most viewed essays, works of art, and keywords on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History website, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year and attracts over 15 million global visitors annually.

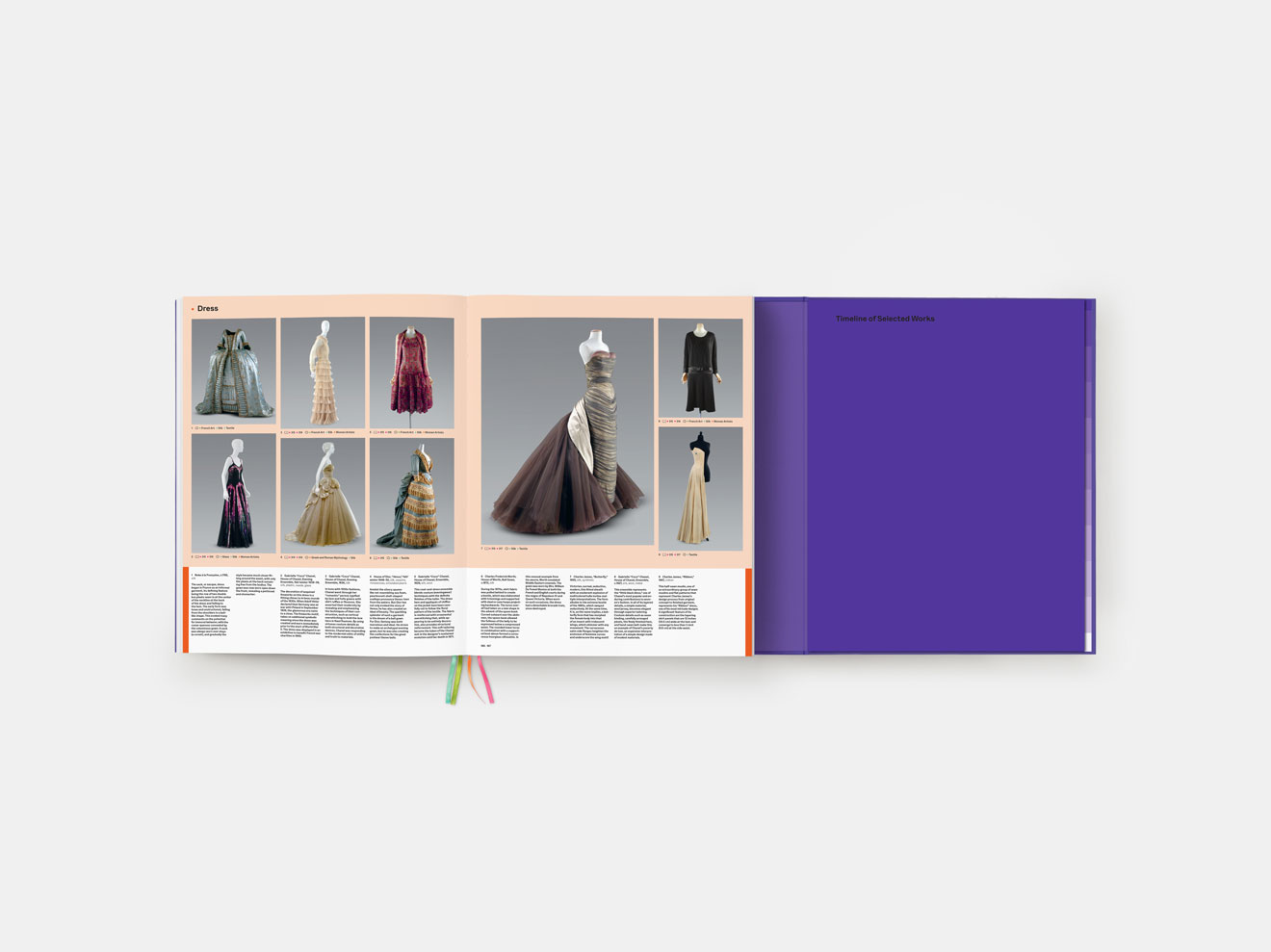

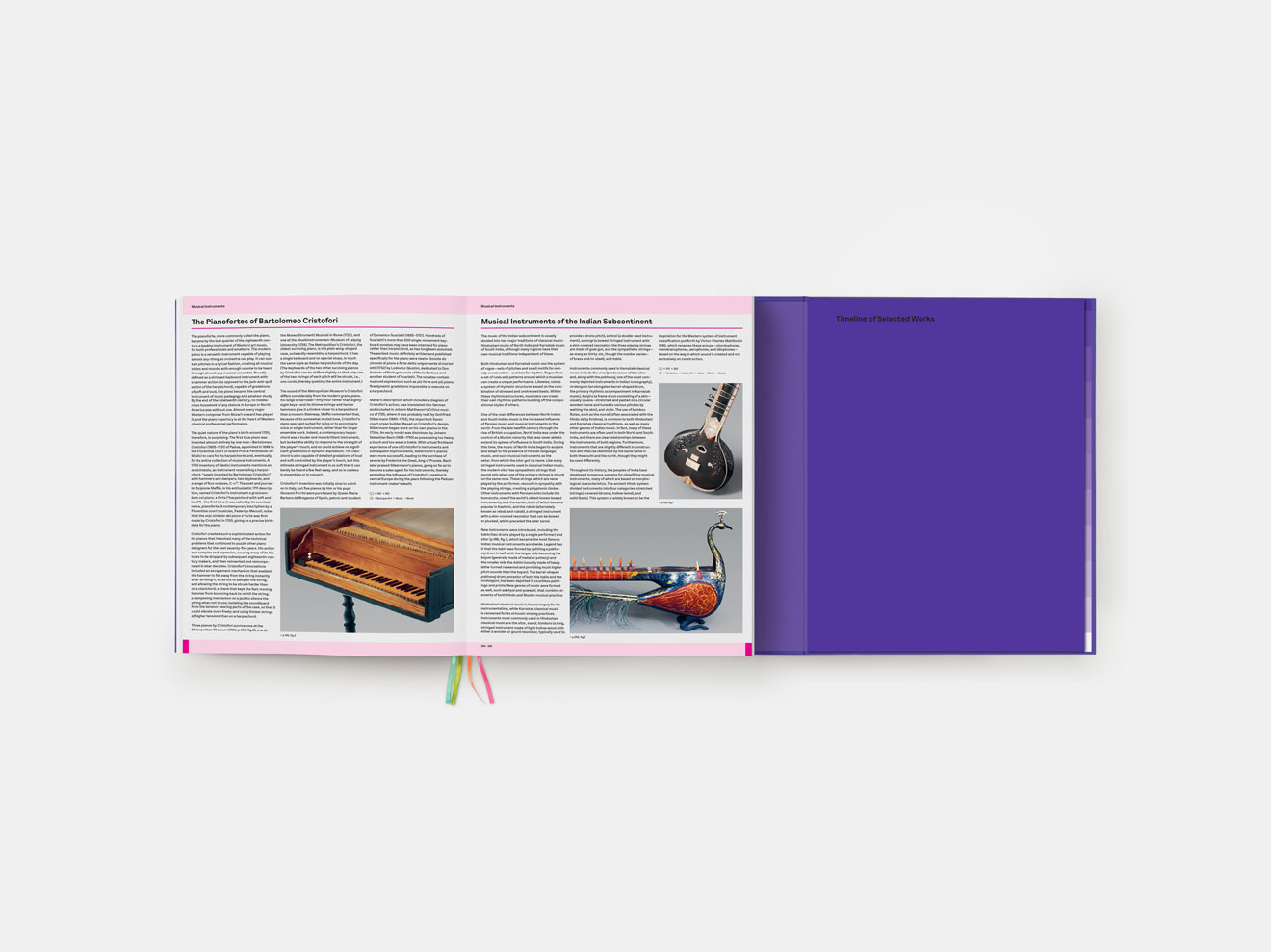

A spread from

Art =

A spread from

Art =

Were there signs in your early life that you might take an interest in museums and fine-art objects? Did you collect anything when you were a child? Did you ever show these collections off to friends or family? My parents were both deeply involved in the arts—my father was an architect, and my mother was a fashion designer. All of our family friends were artists, actors, architects, authors, or designers. As a child, our vacation plans relentlessly reflected their passion for museums. Back then, I would have much rather gone to the beach, but even though I was resistant, these experiences had a significant impact on me. Also, Vienna, the city where I grew up, can be seen in a certain way as a museum in itself, and it has a whole range of major cultural institutions that I got introduced to very early on. But I first visited The Met when I was eight-years-old, and of course, my trip to the Museum was a life-changing experience.

It was my first trip to New York City, and coming from Vienna, Austria, everything in this city felt big, loud, and grand. I'll never forget the experience of climbing up the towering front steps with my sister and entering the Great Hall, with its soaring domes and enormous bouquets of flowers. The scale was overwhelming, and the experience stuck with me. In particular, I remember being in awe of the Egyptian galleries and Jackson Pollock's Autumn Rhythm (Number 30). I am in good company. This painting is the most-viewed work of art on the Timeline, so clearly it also stands out to many of our visitors.

Eventually, what started as a family ritual of museum visits matured into a passion of my own, and then a profession. Here I am at The Met again, still struck by its enormity and still connecting to the artworks in the galleries and in publications like Art =.

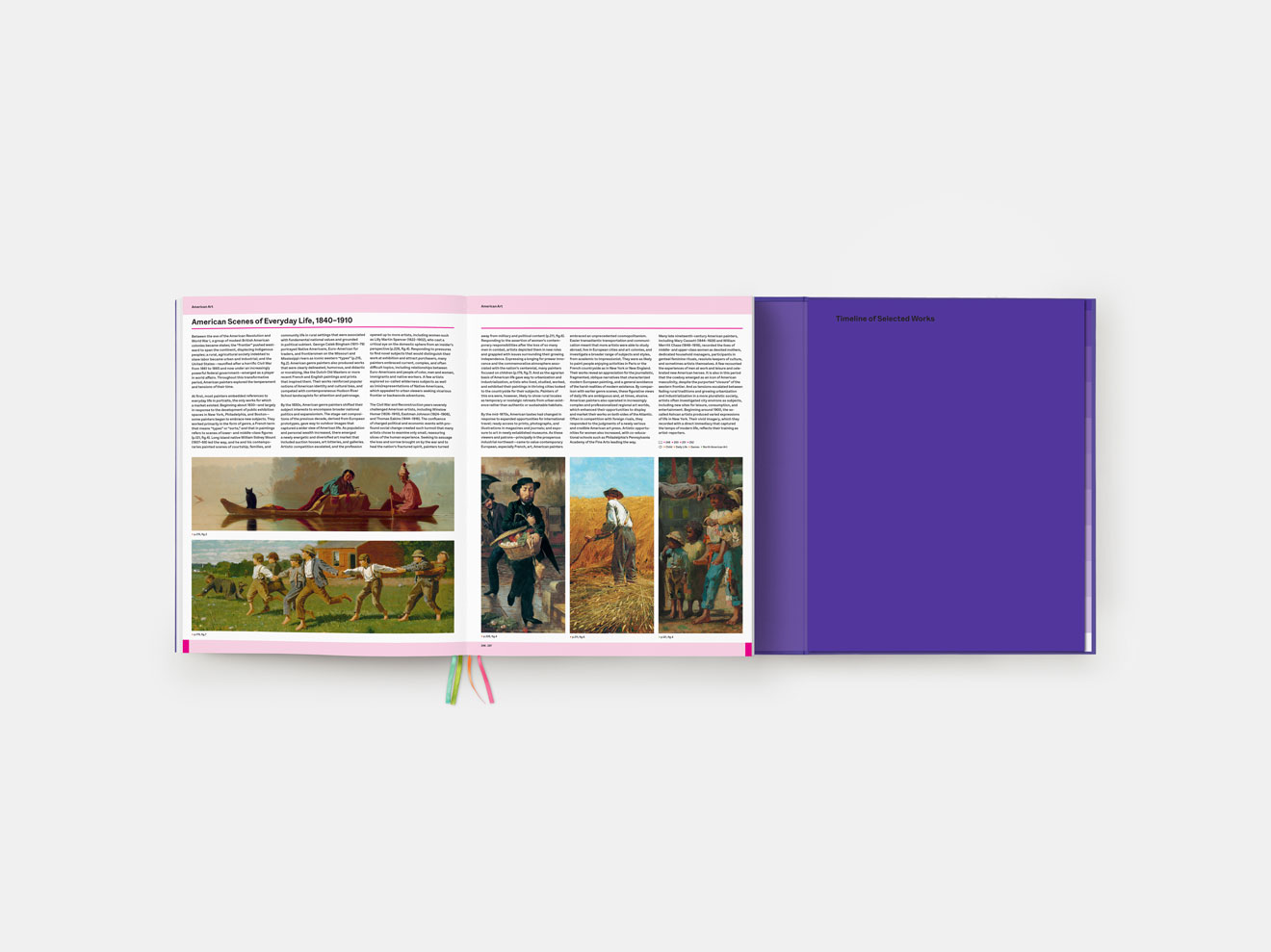

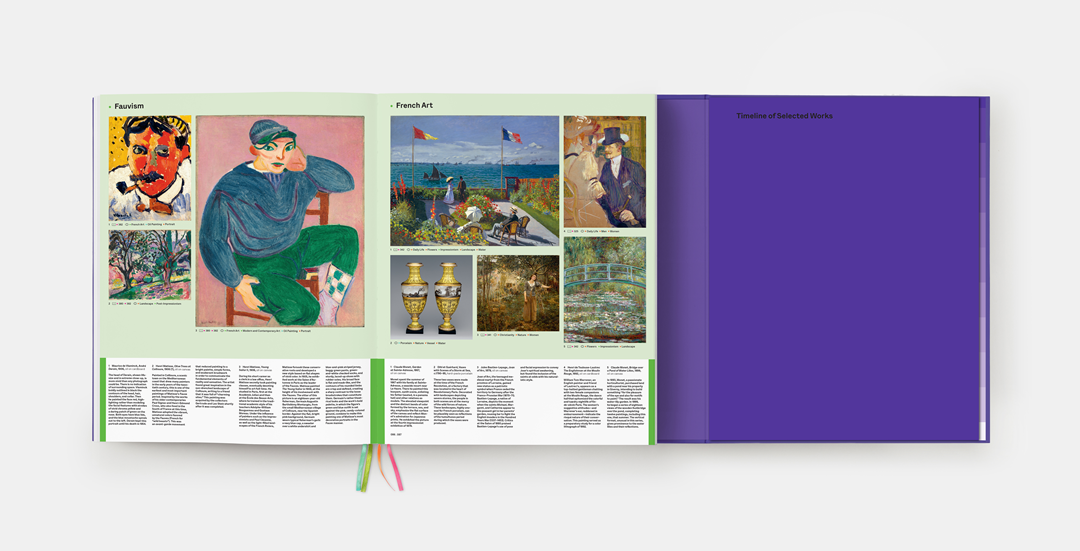

A spread from

Art =

A spread from

Art =

As you've noted, Art = is developed from the Met's online Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. How was this originally developed and how was it expanded in Art =? What advantages does a book offer? The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History was founded in 2000 and was the first significant online art history resource. This project was truly innovative. It began even before Wikipedia. The Met's curators have always reviewed the texts so that the information can be reliably cited. In the early decades of the internet, research done online was often called into question. The Timeline, backed by The Met's stellar scholarship, was instrumental in establishing trust in online sources, something most of us can't imagine living without today.

That said, the Timeline is designed for online viewing, and twenty years of contributions make it a vast resource. Art = condenses the over 8,000+ artworks and more than 1,000+ essays on the Timeline to give readers nearly 900 of the most popular works and over 160 representative essays.

Readers will not need an internet connection, large screen, or search terms to enjoy Art =. The striking color-coded design by Julia Hasting [Phaidon’s Creative Director] allows readers to navigate the contents easily. The book includes ribbons for marking pages, a detachable timeline, a helpful glossary of terms that might be new or unfamiliar to readers, and robust cross-references to explore the contents or read more deeply. We anticipate that the book will inspire readers to seek more knowledge on certain topics, which can be found in our online resources.

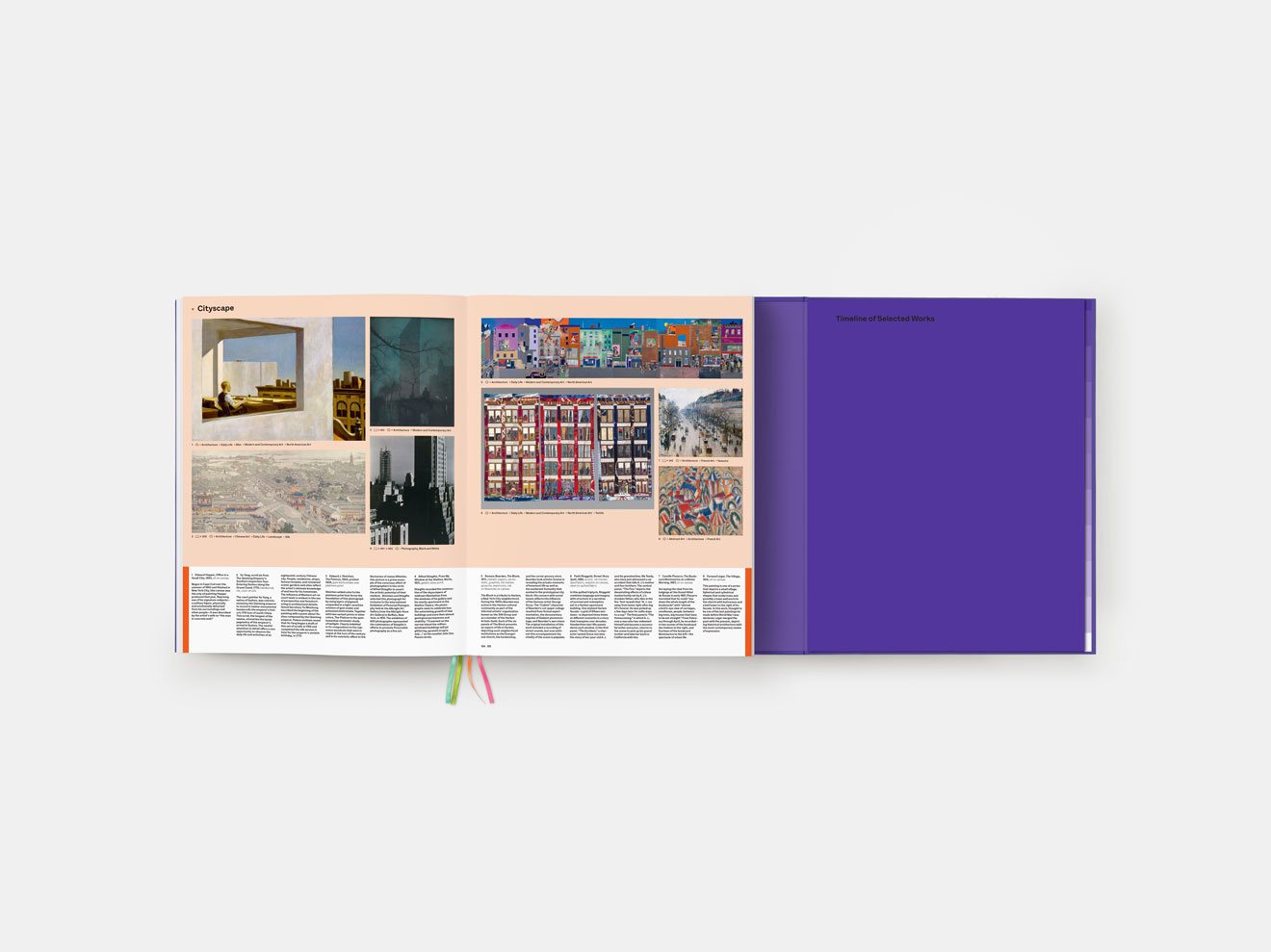

A spread from

Art =

A spread from

Art =

One of the most rewarding aspects of this new book is the way in which it pairs unlikely works together, through its keyword organization. Are there any pairings you were particularly pleased with? Did any of them particularly surprise you? There are so many memorable pairings that delighted me in this book. I'll share some of my favorite examples:

On the pages dedicated to the Animal keyword in the Object/Subject chapter, the "fiery" white horse in Han Gan's Tang Dynasty masterpiece from 750 AD, Night Shining White, is striking placed opposite Horace Vernet's leaping white horse in the 1820 painting, The Start of the Race of the Riderless Horses. Both works are empathetic portrayals of these majestic animals, capturing not just the horses' likenesses, but also their spirit. They also represent a human relationship with animals across time, place, and medium.

The Architecture keyword, which holds a special place in my heart, shows two models of houses, both made of clay at roughly the same time period, between the 1st to early 3rd century AD. One was created by a Nayarit artist in Mexico, and the other was made by a Chinese artist of the Han dynasty. It is astonishing that at the same time, and with similar materials, two artists in vastly different parts of the world created these parallel idealized lodgings that have a visual continuity and speak to the importance of safe and comfortable shelter.

Even in the traditional categories of period, place, and style, this book offers surprises. The Surrealism keyword, for example, juxtaposes two dreamlike works by women artists, one working in Mexico and the other in Argentina. Leonora Carrington's 1937 self-portrait shows her stretching out her hand to a prancing hyena, while Greta Stern's photomontage, Sueno No. 1, Articulos electronicos para el hogar, from 1950 shows a masculine hand turning on a lamp that features a miniature woman as its base.

The Vessel keyword shows two anthropomorphic pottery vessels made 5,500 years apart: one with feet and the other with a face. The earlier one is a pre-dynastic Egyptian bowl, from the 4th century BC, while the other is a Face Harvest jug made about 1850 by an enslaved Black artist in South Carolina. Both works are unsigned, and thus, the creators remain anonymous to us, but they poignantly connect across millennia on these pages.

Finally, the pages representing the Women keyword include several great pairings. Works on these pages range from an Egyptian New Kingdom statue of the regal Pharaoh Hatshepsut to Elizabeth Catlett's 1947 linocut of the commanding Sojourner Truth, both of whom were strong leaders.

A spread from

Art =

A spread from

Art =

Is there one page, or a few pages, that really capture what you love about the Met? It is a section that most readers might not notice, but for me, the pages of the book that capture what I love about the Museum are the acknowledgements. 150 years ago, The Met was founded without a single work of art, but with grand ambition and the simple idea that art can inspire anyone who has access to it. Then and now, our staff has been crucial to realizing and expanding that goal. These pages show just how many members of our team, both past and present, were involved in making this impressive publication that speaks to the spirit of what The Met's founders set out to accomplish fifteen decades ago.

The list acknowledges not only the authors who wrote the texts, but also the photographers who captured the nearly 900 works shown in the book, the editorial teams in our Digital and Publications departments who organized and synthesized the information, and the curatorial advisory group, which shared ideas and reviewed all the texts for accuracy. This book would not be possible without these people, and so many more, who serve the public by protecting, studying, and sharing the world's most meaningful representations of culture and society.

None of us have a wholly complete knowledge of art history; we're all, in a sense, life-long learners. What did you learn from this book? When I first heard about the publication, I wondered how a vast and complex website could be translated onto the printed page while still transmitting the experience of linking works and concepts and encouraging individual exploration. This book demonstrates that this is not only possible, but the format provides new dimension and insight.

When you picture the ideal reader of this book, who do you have in mind? What might he or she get out of it? The ideal reader should have a sturdy table or bookshelf to hold this large book, which includes more texts and works of art from our collection than any other publication in The Met's history. Jokes aside, this book has something for anyone, from the novice to the professional art historian.

There are beautiful images and details that don't require any reading to appreciate and detailed texts for those who want to read more deeply. The book is meant to grow with the reader's interests and designed to be revisited again and again. Readers will find that their experience changes each time they open the book, and they can follow the connections in both a linear and random order.

This would be the perfect book for families who may have one book about art in their home, and for those who visit the Museum or who plan to visit and want to remember their experience, and it is also the perfect book for those lovers of art and culture who may never get to visit The Met. It certainly also looks very good as a beautiful, colorful object in the home!

A spread from

Art =

The Met's sites are shut at the moment. It must be a very difficult time for the organization, but there might be a few positive aspects. Has anything fruitful come out of the pandemic? It is difficult to say that anything good could come out of a situation that caused so much suffering. Through these tough times, we have tried to give people solace and hope, through our strong social media presence and other online offerings. Our website includes MetKids, which introduces the Museum to a younger audience; MetPublications, where more than 1,700 of our publications from over five decades are available to read, download, or search online for free; and of course, the Helibrunn Timeline of Art History, which we've discussed at length. This book presents another way of reaching our audience at home while we are not able to be at The Met.

How has it been for you working at the Met while it's been closed to the public? What are the aspects you miss about the Met and what are the ones you are most looking forward to when it opens? While I've had the opportunity to return to the Museum during the lockdown, the experience hasn't been the same. It is somber and lonely without the visitors and staff. As the Met's founders realized, a broad range of people are essential in the Museum: families enjoying the art together as my family and I did many years ago, school groups engaging through tours lead by our colleagues in Education, couples meeting for a first date, researchers making a new discovery in our Watson Library, first-time visitors who have waited their whole lives to see the works of art in our collection, and regulars who revisit their favorite galleries—the list goes on. The Museum is full of stories and full of people, and that is what I miss the most.

While the Museum is currently off-limits to the public and most staff, I want to recognize the essential workers who are there right now. We are so grateful to them for protecting, cleaning, and maintaining the building and the works of art, and we are honored by their service and professionalism. They are the ones that make it possible for the Museum to reopen so that it can once again become the center of human connections with great works of art.

A spread from

Art =

A spread from

Art =

Has anything in Art = influenced any changes you might make to the Met once it opens again after the pandemic? The focus on creating connections across time and cultures, which governs Art =, is something I have been thinking about for some time.

In many ways, readers will move through the pages of this book much like they would move through galleries during a visit to the Museum. For instance, they can select a linear path through one department's holdings, perhaps lingering in front of a familiar favorite, or they can proceed randomly, finding new favorites when an unfamiliar work catches their attention. This book's clever organization encourages unexpected or surprising encounters, and more and more we are looking for ways to amplify that experience in our galleries. One recent project that mirrors the approach of the book is the Crossroads installations, which will be on view when the Museum reopens in August.

The Crossroads installations are staged at three prominent intersections in The Met's galleries. Displaying works drawn from diverse areas of the collection side-by-side, Crossroads tells thought-provoking stories about shared ideas and artistic forms. Art = is another example of how approaches to curation are changing to provide a richer, more nuanced understanding of our collection. We will certainly continue to see more cross-departmental collaborations that I hope will lead our visitors to discover infinite new connections.