Through sculpture, performance, drawing, installation, and more, artist Jimmie Durham tackles issues of national narratives, hegemony, and marginalized non-Western perspectives. Particularly, Durham's work revolves around his years spent working with the American Indian Movement and his claims of Cherokee ancestry—and the politics at play when an Native American tries to enter an elitist and disparaging art world. (He's recently come under fire from Cherokee artists, curators, and other professionals who say that Durham is in fact "not Cherokee in any legal or cultural sense.")

At The Center of The World, his first stateside exhibition in over twenty-two years, brings Durham back into the fold at a time when artists are growing more critical of the hegemonic art world and the rigid boxes "identity" can trap them in—ideas that Durham challenged consistently throughout his career. The artist's momentus retrospective opens next month at the Whitney Museum of American Art, following earlier stints at the Hammer Museum in L.A. and the Walker in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

In this excerpt from Phaidon’s monograph on the artist (recently re-released, revised, and expanded), Durham talks to curator and historian Dirk Snauwaert about being "an artist first and an activist second", the problematic New York art world of the 1980s, and how, in his eyes, “you can’t lose your own identity.”

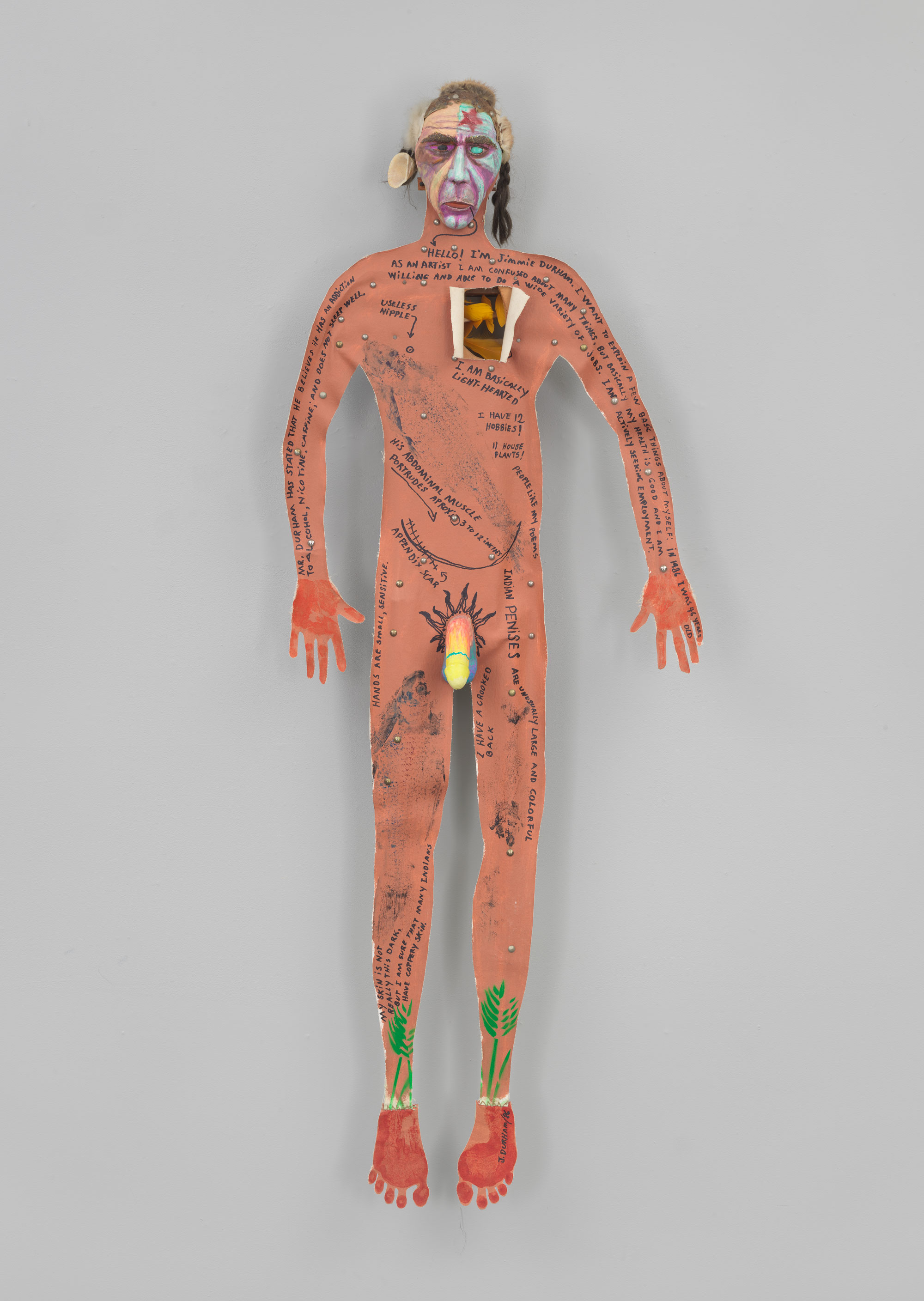

Jimmie Durham, Self-portrait, 1986. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee. Digital image ©Whitney Museum, N.Y.

Jimmie Durham, Self-portrait, 1986. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee. Digital image ©Whitney Museum, N.Y.

Dirk Snauwaert: You worked as an artist before you decided to become an activist, and then you went back to art again. Art and activism are strangely intertwined in the work of several artists from the late 1970s and 80s. Do you think that your work as an artist gave you a different point of view on activism, and vice versa?

Jimmie Durham: Of course it must be true, but I never thought of it. People usually assume that I began as a political activist and then went into art. And if not, people often kind of assume that since I was a political activist, that must be more legitimate for me, that it’s more authentic for me in some way and that art is the same struggle with different weapons. The assumption is that there is a difference in working, but it’s not so different, actually. I don’t think it comes from something obvious like racism, but if you’re looking at a European or a white American or a white South African or something, who had a similar history as a political activist and artist, I think the assumption would always be the opposite: that this artist had a political situation confront him or her and had to react, which is the case of Athol Fugard, the South African playwright. He was just a playwright, but he was from South Africa so he was confronted by a situation he could not deny. And everyone understood that that was true. Everyone said immediately that his first job was artist, his second job was political activist. With me the assumption is that I began as a political activist and then chose art when the struggle failed. In New York and certainly in Europe, people have been surprised that I am a serious artist, that my art does not stop at the boundaries of identity struggles.

But then in your ‘pre-history,’ let’s call it, were you already consciously working as a critical artist? And was this level of consciousness later transposed, transferred to a political activity that you further developed?

Even now I often have to defend myself from accusations by my own crowd, politically active Indian people of being an artist first and a political activist second and I have had to defend that and say it’s legitimate. When I went to Pine Ridge, to Wounded Knee, I went straight from Geneva and put myself in the American Indian Movement just as a worker, not as a big shot, and stayed completely submerged in the organization for a long, long time. I was in a very privileged position that other Indians didn’t have. It wasn’t that I was smarter, it was that I had a privileged position to learn things. So I came back to Pine Ridge, throwing myself into the struggle right there on the reservation but with already a great deal of mental space that was allowed to me by the privilege of having lived in Geneva. Before going to Geneva I was pretty typical in that I wasn’t educated. There is always a tendency to be kind of criminal as a way to get by, as a way to do this, as a way to do that. I was rough, a stupid kid. I was a typical Indian in that sense, but because of meeting different people I was an artist. I was not a good artist, but I wasn’t a horrible artist. I was not a completely dishonest artist, I was never an artist with the idea of doing art as a way of representing some Indian-ness for sale. Not once. I had a mixed up idea that it was a way to make some money, but certainly not very much money; not as much as I could make driving a truck, not as much as I could make as a carpenter. You had more freedom as an artist, more time to yourself, so you could take a cut in pay, that’s the way I thought of it. I tried to see what sort of art could work, what art could do, but with no vocabulary, no discourse, no education, so I was groping in the dark, but I wasn’t pretending that it was a beautiful twilight. I had my own something as an artist, as an Indian who was an artist. The leadership of the American Indian movement as a group were like me, rough, uneducated, doing whatever job came along. For many people in the American Indian Movement, the destruction of the movement was the destruction of the person. This is what I have seen over and over in generations of Indians on reservations. The destruction of the plan of that moment is the destruction of the person, you can’t see it another way, you can’t see anything else that could happen. And you make your personhood from that thing. It’s not so easy for an artist to make a person, to make personhood, it’s not the thing they want.

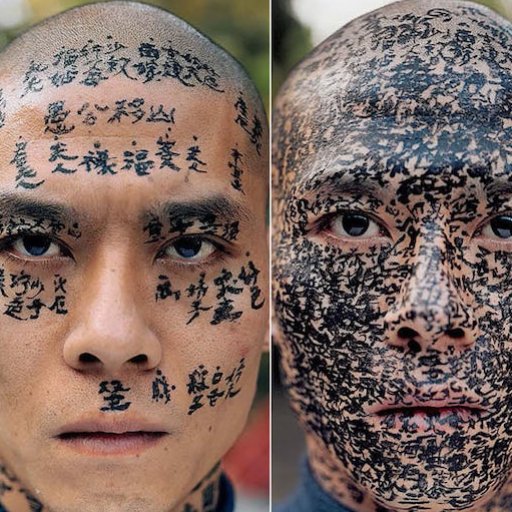

Jimmie Durham, Malinche, 1988-1992. Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium. Image ©S.M.A.K. / Dirk Pauwels.

Jimmie Durham, Malinche, 1988-1992. Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium. Image ©S.M.A.K. / Dirk Pauwels.

...It is intriguing that you never chose any of the defensive reactions that exist in art, the hermetic, non-communicative position, like hard-edged abstraction, that must have been popular at the academy [Durham attended] in Geneva.

Again there I had a privilege of very early on, or I had a potential privilege of learning an easy lesson, easy because it was so obvious. I could have become a Fritz Scholder, who was the famous Indian artist in the US, who paints pictures of Indians. I can paint, I can do all the things that artists do, I can sculpt, I can do all the arty things. I had the privilege of knowing to refuse that at an early age, because I could see how silly that was, it was so obvious. This Indian art world is so little, it makes everything quite clear. You have to avoid answers at all costs in a certain way, at least I knew that from an early age. The other privilege I had was that of seeing Geneva and its stupidity; that was a privilege because it was something that you had to refuse, you couldn’t say yes, I will participate.

There was a second part of this transfer, after your activist period. How did you formulate the political discourse that you had before and join it to your previous art practice?

I left the Indian movement and my idea was to write a history of the Indian movement of the 20th century, to put our movement in its proper context. It was all too close and it was all too hard. I had no money; we were shoplifting for food, we were really in bad shape for money so at the same time I was free for the first time after a very intense decade. We were on the job 24 hours a day, so in my free time I started doing artwork. But the artwork I started doing was still within where I had just come from, so I did a series of collage assemblage paintings. They were about our political situation, they tried to have nothing to do with aesthetics, which I had already been trying to do in different ways. You would get something from them emotionally and visually, but not at a typical aesthetic level, something much stronger, I thought, in a kind of romantic way maybe, but the reason for them was a political text. Each one had a text about a situation at the moment, what they’re doing on the Rosebud Reservation at that moment which could be stopped and should be stopped. Death and destruction kinds of things, poverty and where we are. And I wasn’t making them with any kind of idea in mind, I was just making them. I didn’t have an art scheme, I thought my job was to write that book, not to do art. I was just trying to continue a conversation with the world that the world never wanted and still doesn’t want. The way that I normally knew to do it was with the plastic arts instead of with words; it’s just a normal way that I work, that I speak. Then the artist Maria Theresa Alves went to apply to Cooper Union, a little art school with a big reputation in New York. This was still in 1980, I think, and she met a guy named Juan Sanchez, a Puerto Rican painter, whose work she had admired. He was doing a show called Beyond Aesthetics of third-world artists who were doing strong political work. So he came to our little place in New Jersey where we were living and looked at those collages and said, yes, yes, I want all these in Beyond Aesthetics. Then they were very popular, people liked them very much. I felt very insulted; I saw the weakness of doing that kind of work. It looked like the art crowd of New York was being entertained by the sorrows of my people and I was the agent who allowed them to be entertained. I felt that I had betrayed my own folks and betrayed my own struggle because the work was popular. I had to stop and say, if I’m going to do art once more I have to do a little research about art, once more I have to go back to see what the hell we’re talking about with art. So that was the third time I had to do that in a very serious way, and all three of those times, it was a time of success, not a time of failure, a time when I could have gone on to become an angry Indian political artist, which is a beautiful trick the art world likes to play on you. And they played it on Juan Sanchez. He’s a good artist; he was doing marvelous paintings about that time, outstanding, without any idea of what sort of thing painting should be, always about the political situation in Puerto Rico. He was the darling for not even six months, and then they said no, not political painting, and then suddenly Jean Michel Basquiat came along. And I love Basquiat, I love his work, I have no problems with that at all except when I look at the history of New York at that time, the history of the early 80s when things were beginning in New York for the minority syndrome, it’s just a disease. What was the discourse in the New York art world that said yes to Basquiat and no to Sanchez? It was, you can’t have this blatant political message, we don’t like that. It had nothing to do with whether or not this was good in the artwork. But their discourse and watching how that all played out—I suddenly realized I was in the middle of an art discourse. I was in the middle of a heated conversation about art, and that was completely inseparable from politics.

Was that when you also started to reflect very strongly about questions like what is political engagement in art, how can it be transmitted, and how can it be accurately communicated without losing yourself in the discourse? How can one address different audiences and not just oppositional patterns of dominated/dominating, and can aesthetic engagement also be political engagement? That was also the time when other artists emerged who used agitprop and advertising-like, aggressive media techniques.

It was exactly what you described happened at the time. I said, I can make these people part of another audience, I can change these people’s expectations in some way. I can be part of the discourse by completely disagreeing with it, but I can do it intelligently instead of just making an interruption. I can make this audience itself strange to itself and I can try and expand an audience and make it not so silly. At the same time I was working alongside this artists’ organization, the FCA, they did a newspaper and so on. Once I had changed my mind about what the New York art world was, then I started working with them. I started knowing everybody, Basquiat, Haring, Rosenquist, Oldenburg, and Sol LeWitt, and thought of them as friends. I didn’t know the right critics but I knew some writers. I assumed that they had similar thoughts about me, and I was quite surprised that I was not perceived as a fellow artist exactly, I was perceived as an Indian artist. I was kind of stunned by seeing that at least some people had this perception. No one had a perception of me as a fellow artist because I did not have the proper signs in my work, and that was exactly what my work was trying to do, not have the proper signs. Let’s see how we can be postmodern, that’s what I wanted, a postmodern situation.

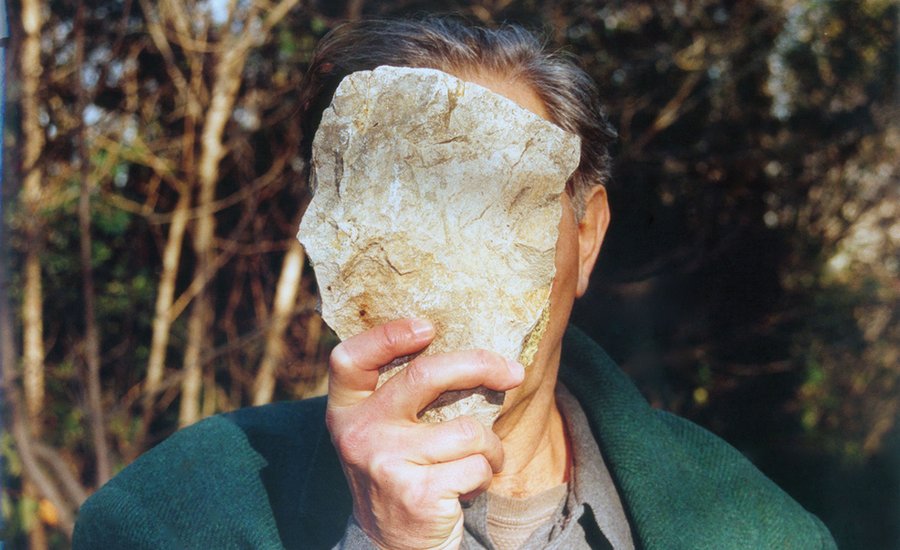

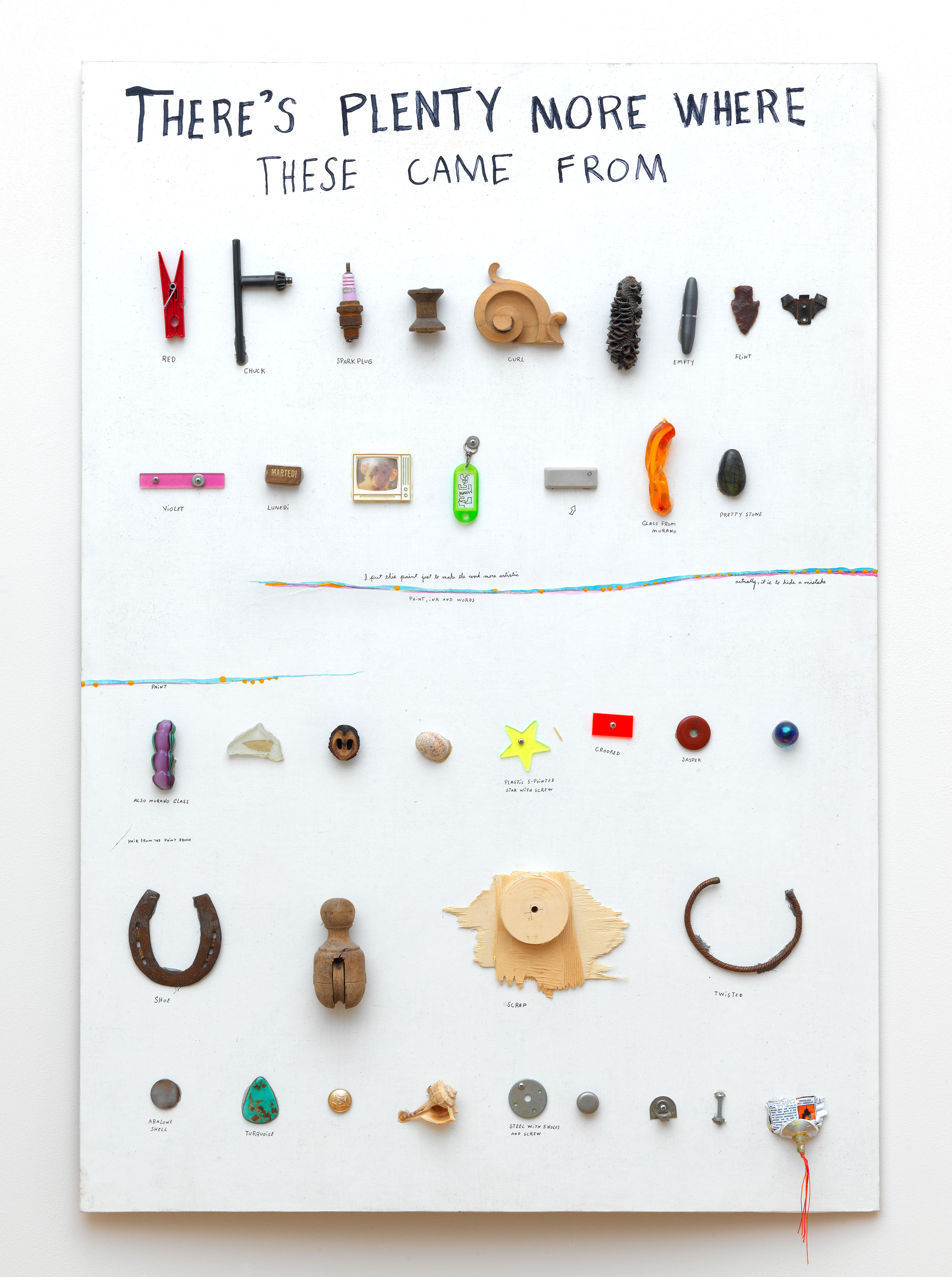

Jimmie Durham, THERE’S PLENTY MORE WHERE THESE CAME FROM, 2008. Private collection, Mexico City. Image courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

Jimmie Durham, THERE’S PLENTY MORE WHERE THESE CAME FROM, 2008. Private collection, Mexico City. Image courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

...In relation to the current historical moment, there’s this “the dream is gone” feeling. And I think now that artists feel a greater responsibility in intentionally making art. I’m not talking about sociology, I’m talking about art. Maybe aesthetics, even, because it always comes to this point.

Except you can’t separate the two things, you really can’t separate sociology and aesthetics.

No, but there has to be a certain aesthetics in the work, otherwise…

There has to be and here is a difference. I will talk again about two artists, both friends of mine, I respect both of them. Mel Edwards, a Black artist my age, my generation, he has a teaching job so he has a life, he makes art that talks about the Black situation. David Hammons doesn’t talk about the black situation, except that that’s what he always does. From way over in left field, from a different place, from a place that turns out to be strangely within the art discourse—the discourse we wanted all along. I think in this century there is art discourse, Duchamp, Joseph Beuys, a certain list of artists that we think tried to take away limits in some way that was not so heavy-handed. This is the art discourse that we find interesting this century, I think, the art discourse that is still not recognized. David Hammons is doing his work completely consciously, he’s not doing it innocently in the least bit. He’s using the full discourse available to him, but it is in line with this other art discourse. So he is bringing his struggle, the struggle of his people, the absolute horror and hopelessness of Blacks in the US, to that discourse. They still try to refuse him because no one wants Hammons today, but they can’t. He says yeah, all of this, and the American Black experience is part of that, it’s not excluded from that. It’s a genius thing to say, it’s so important to say that, and it’s exactly the thing that cannot be said. And it’s at that point that he gets the rejection that he says, see, see, now you can’t refuse me, now you have admitted.

So does that also mean, and this is perhaps another contradiction, that you have to take up West European discourse?

That is the art discourse. Art is a European phenomenon, it does have a European history. Europe is a human project, it’s not a European project, we have all contributed. But because of certain power structures everyone says it’s a European project. I then say, there is this marvelous art history in Europe; it’s so good I want to be a part of it. I want to join that discourse; I don’t want to interrupt it or stop it. But I want to join it as me, I want it to be as big as me, which was its original intention.

Doesn’t one lose one’s identity? What does one give in?

You can’t lose your own identity. I wish I could lose my own identity. All of my life I wish I could. The problem is you can’t.