Happy Friday the 13th! In this excerpt from Phaidon ’s upcoming brand-new book The Artist Project: What Artists See When They Look at Art , seven artists dust off the cobwebs and discuss some seriously out-of-the-crypt artworks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection and the surprising, unexpected influences these ancient works of art have had on their own work.

Even in their old age, the following seven works have withstood the test of time, proving once and for all that age ain't nothing but a number, and (more importantly) that great art lasts forever.

Power Object (Boli)

19th-First Half of 20th Century

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

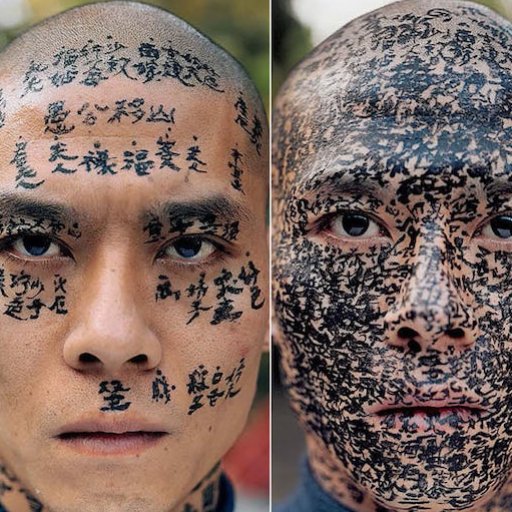

There are so many things that are visually louder or pull me in more readily, but the boli is the object that I feel like I’ve learned the most from. So much of its meaning as a sculpture is bound up not in what you can see on the outside but what it contains within. That was an immensely exciting idea to me: that sculptures could have secret places.

The boli is used by the Bamana people of Mali and only seen at certain times by people who have gained the right to access it. It has a structure inside that’s much like a digestive tract. Water is poured through, and you can drink it from the other end. A great way to think about it is less as a sculpture and more as an instrument—these objects can be used to perform. When in use, people pour blood and other materials over it; its final shape is determined by the encrusting of all of this material.

In a number of ways, the boli is a real challenge to the sort of conventions around art that have built up in the West. We’re very used to the idea that you have a flash of inspiration and then you’re done. That’s not necessarily the way it happens. This sculpture is made in the same way a snowdrift is. It finds its final shape as a result of many forces acting independently.

Nayland Blake. Work Station #5, 1989. Steel, glass, aluminum, leather, plastic, rubber, and cleavers; 54 1/2 × 24 1/2 × 55 1/2 in. (138.43 × 62.23 × 140.97 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dare and Themistocles Michos in memory of John Caldwell © Nayland Blake. Photo: Ben Blackwell

Nayland Blake. Work Station #5, 1989. Steel, glass, aluminum, leather, plastic, rubber, and cleavers; 54 1/2 × 24 1/2 × 55 1/2 in. (138.43 × 62.23 × 140.97 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dare and Themistocles Michos in memory of John Caldwell © Nayland Blake. Photo: Ben Blackwell

In the West we’re feeling a sense of alienation from contemporary art because it’s so disconnected from a particular place and time. This object is a thing that a community makes. It carries with it this resonance that comes from everything people gave up in order to make that form. That, as an idea, has its own power.

As you look at this, ask yourself the questions: What do I think is powerful that I hide? What do I overlook? It’s what’s on the inside that counts. And that’s a rare experience. It’s about more of a sustained relationship.

Headress (Ci Wara): Female Antelope

19th-Early 20th Century

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I like to think of myself as a perceptual engineer. Perception is an outgrowth of awareness or education. I was in high school from 1968 to ’72, just after the riots in the sixties, the Kennedy assassination, Martin Luther King, which all led to the Black Consciousness Movement. That influenced our art department, and we began to discuss African art in the classroom. We were not searching for Africa, but they put Africa on us. One assignment we had was to choose a piece to recreate, and I chose the ci wara headdress.

I could extrapolate and say that because a ci wara headdress was used ceremonially as part of an agricultural ritual, its connection to the land appealed to me. But I’m only aware of that function through gaining knowledge about it. At first glance, it was just the graphic quality, the symmetry of it, that appealed to me. You can pretend it has a front view, but the front view doesn’t reveal its form. Rather, the left and the right side are necessary to understand it. I’m of that age; I read MAD magazine, Spy vs. Spy —that’s the same face.

There’s just expression, and life. This ci wara has a small figure on the back, which I see as a mother-and-child image. I read everything as living. I can sense the power in objects that are designated as ceremonial.

Willie Cole's Burning Bed is available on Artspace for $800 or as low as $71/month

Willie Cole's Burning Bed is available on Artspace for $800 or as low as $71/month

Of course, years later I began to make ci wara out of bicycle parts. Someone told me that the words ci wara mean “work animal,” and in the United States the bicycle is a work animal, at least to me. My ritual objects come with life and history because I create them from things that people use and handle. I assume that the carver may have considered the life in the tree, since these sculptures are carved from wood. The life in this first existed in nature, and the artist is aware of that. After it’s carved into sculpture, it’s going to have to go through some ceremony to become empowered.

Without education you wouldn’t be able to recognize the object as something from the past. The quality of the wood and the patina could suggest that to you, but if you just look at the form itself, it could be from the future. Education makes us see things differently. It inspires everything I see. So suddenly, Africa is in my world, and my reference points for shapes and designs are going to come from that, too. It made me start to explore the term African American , and I decided at that point that I would make African things out of American things. The ci wara headdress opened the door.

Rosary Termial Beads with Lovers and Death's Head

ca. 1500-1525

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I believe that most humans are obsessed with death, because it’s the one thing that we just can’t know anything about. I find myself coming back to these themes over and over again. I was really struck by this little ivory carving. It’s a rosary bead about two-and-a-half inches tall. What you see initially is a young couple in love. It’s funny because to my eye they don’t look young. They actually look kind of tired. Their eyes are droopy, but they have tiny smiles on their faces. As you circle around the object, a skeleton appears. It has drapery over its shoulder, but if you look closely, you’ll see that a salamander is crawling into the skull and coming out the mouth. This is death rotting in the ground—a reminder that this is the destiny of all humans.

The artist connected the three figures by mirroring the drapery and the gesture of the hands. The man is holding his hand above the woman’s, and the death figure in the back has his bony skeletal hands in pretty much the same positions, but does so completely alone. It’s another way of reinforcing this idea of mortality.

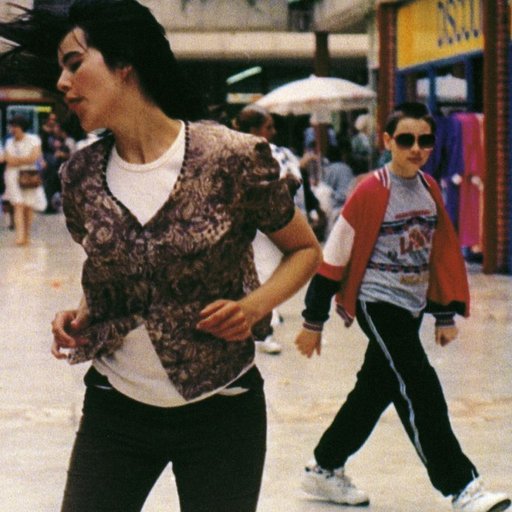

Moyra Davey's Diaries III is available on Artspace for $729 or as low as $49/month

Moyra Davey's Diaries III is available on Artspace for $729 or as low as $49/month

Another thing I noticed is the plant motif at the base. It’s stylized and abstracted but it still suggests something unfolding. The emerald might also represent fertility and nature. We have life and we have decay.

The idea of holding the bead miniaturizes death. I can almost see a sense of humor. It’s literalizing what happens to the body. There’s something almost comic book about it—each of those little worms and caterpillars on the skull.

The bead doesn’t freak me out. There’s something kind of beautiful about it, in the same way that cemeteries are beautiful. They’re gardens, and we can go to these places and enjoy them. It reminds you of death, but at the same time you can be in denial because the exquisite nature of the object or place takes over, and you can lose yourself in that.

The Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art

(also known as "Visible Storage")

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

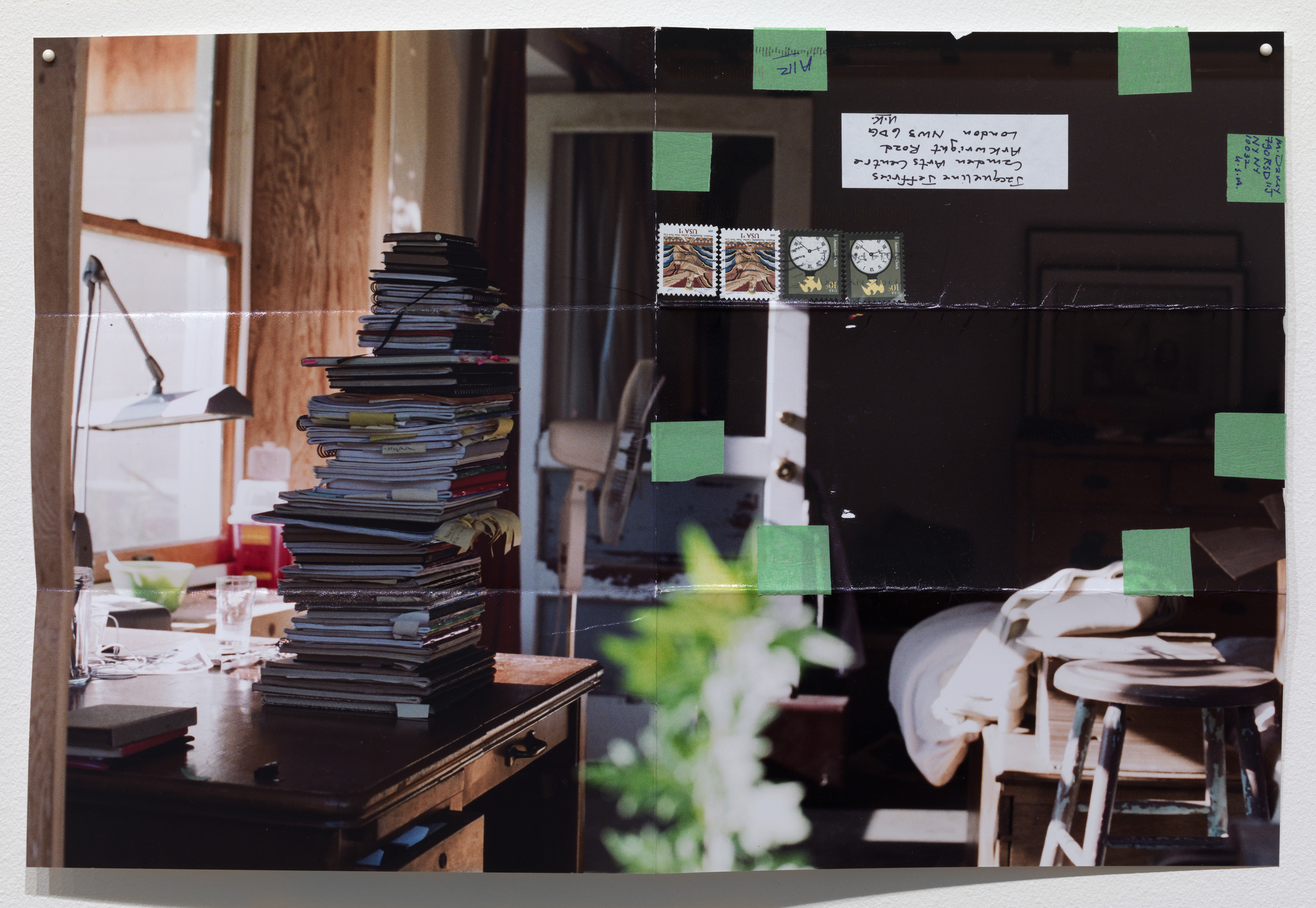

I remember finding the Luce Center completely by chance. My first impression was that the entire place was some kind of weird contemporary art installation. I actually asked a guard about it, and he said, “No, this is storage that was all made visible so that the objects are always on view.” Now I visit the Luce Center every time I come to The Met because it always gives me ideas. The connections between one object and another are very loose, and they are not preconceived. It’s like you are at the vegetable market looking at the vegetables before they’ve been cooked. There are perfume asks, Tiffany lamps, decorative paintings and sculptures, grandfather clocks and doorknobs, paperweights—it’s a wealth of stimuli.

There is an area of the Luce Center filled with frames, which I think is a great metaphor for the museum as a whole. The museum itself is a huge frame, a huge pedestal. Outside the Luce Center, the rest of the museum suggests an idea of quality: What makes a work a high-quality object or an object that represents a certain point in history? When you see one piece by itself, separated from its context, all of a sudden it can become a masterpiece—something very precious and important. Perhaps because I come from Brazil and I grew up during a military dictatorship, I am very allergic to propaganda or any structured kind of information that comes my way.

At the Luce Center, the sheer accumulation of objects and their casual taxonomy make it like a semantic maze. You’re trying to find meaning, and these things are not really leading you in any way, they’re not asking you any questions—they just are. You have to look without prejudice. It leaves it up to you, the viewer, to make up your own narrative, to create your own story. You’re not just looking at something because somebody told you it’s good. You have to figure out how to find your way around a place where you have access to everything at once. It’s like the Internet, but it’s material. You feel its physical presence. I often say that art is only alive when there’s somebody in front of it, so the visible storage is a beautiful idea.

The fact that you have a great percentage of the collection in the Luce Center makes you think. It prompts you to meditate on the idea that most of the information you receive is manipulated in one way or another, is somehow crafted, and is in a certain way biased. The Luce Center is transgressive in that it empowers you. It makes you think about the mechanisms of the museum: how things get shown, and how things do not get shown. It’s quite refreshing. It’s like the anti-museum.

The Met Cloisters

Fort Tryon Park, New York City

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I have always gone to The Met Fifth Avenue to sit and think and look at work, but The Met Cloisters is, in itself, a work of art. Even in its name: it’s cloistered, set apart, and self-enclosed. It’s like another world floating in the clouds. I’m from Brooklyn, and when I was growing up, the Cloisters might as well have been in the clouds.

In those days Brooklyn was nowheresville. It was where you wanted to get away from, to move toward high culture. And what could be higher than a medieval setting way up at the top of Manhattan?

My first exposure to the Cloisters was in the early sixties, when the medieval world was very much upon us. Monotonal music was important, and medieval representation suggested the flatness we were taught to seek in Abstract Expressionist painting, which was what I was doing as a student. It was immensely satisfying seeing the way that edges and corners were dealt with in medieval art versus the focus on centrality of later works. For example, a millefleur background where everything is clear and individual, like those often found in medieval tapestries, forms a whole field of representation with potentially limitless boundaries.

Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Single-channel digital video, transferred from video tape, black-and-white, sound, 6 min., 9 sec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Henry Nias Foundation Inc. Gift, 2010 (2010.245) Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Single-channel digital video, transferred from video tape, black-and-white, sound, 6 min., 9 sec. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Henry Nias Foundation Inc. Gift, 2010 (2010.245) Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Medieval art also opened a space forbidden in Abstract Expressionism, which was the narrative. As a first-generation Brooklyn Jew, I was trying to see where I fit in with the medieval religious narrative. I had a religious upbringing, and the only way to really understand Christianity without feeling alienated or overwhelmed by it was to look at its representations. Medievalism provided a way to think about roots, origins, and community. Tapestries were produced by crews of artisans working together, creating a communal product. They were artists creating in a humble, as opposed to a singular genius, way. What we projected onto the medieval world in the sixties—simplicity and harmony—most distinctly wasn’t there. This is what we were craving, after experiencing the Second World War and the fifties and McCarthyism and the realization that civil rights were only enjoyed by white people. Looking at a world where those things appeared to be under control was reassuring.

I love the Cloisters for its retreat quality, but it’s not a spa! The great chain of being is apparent in the works on display there. You go there to be exposed to ideas, and I hope that’s what we want from art.

Architectural Elements from North Family Dwelling, New Lebanon, NY

ca. 1830-1840

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The more I build things, the more I develop different techniques and idiosyncrasies that I try to repeat that are, in a way, a reflection of me. I feel like I’m successful when my work is a clear expression of my beliefs.

The Shakers’ work is a clear expression of their ideology: their austerity and dedication to work and belief that to work is to pray. That’s something I live for. I don’t take vacations. I consider them to be a waste of resources. The only true resource that we have as human beings is time.

Look at every object in this space and imagine every object in your bedroom, and you realize all the crap that you deal with. Everything in this room is there for a purpose; there’s no decoration. You hang your coat on a hook on the wall. You hang your chair on a hook on the wall. The bed: the wheels turn sideways so that you can move it to clean it. These were people who, through the narrow focus of their beliefs, invented incredible things, like little tilters on the backs of the chairs, which always seems ironic to me because the idea in this context of leaning back in a chair seems so decadent and indulgent.

The materials the Shakers used are as brilliant an innovation as their designs. Most of the furniture was made of pine because it was abundant, cheap, and very easy to cut. There’s also a humility with pine. Much of this furniture is unpainted. We have a saying in the studio: “Never paint a ladder.” That’s a rule, because you can’t see cracks develop if there’s paint. It’s also a nod to the idea of never covering up your past: embrace your road. I think this idea is especially important in our time, when we have things like iPhones that have no representation of how they’re made; there’s no evidence that a human being was involved. In the Shaker pieces, you can see the joinery. You can see where someone wove cotton webbing for the seat, and that someone led down the chair—very carefully. You can see that it’s handmade.

Tom Sach's Deluxe Racing Set is available from Artspace for $2,500 or as low as $220/month

Tom Sach's Deluxe Racing Set is available from Artspace for $2,500 or as low as $220/month

To me it’s important to be able to say, “Hey, someone was here making this thing,” when you look at the object—to embrace the individual. It’s a very American idea, and it’s interesting to say that in a communal society like the Shakers’. I think that’s the one real advantage that art has over industry—it’s an expression of the individual.

Mastaba Tomb of Perneb

ca. 2381-2323 BC

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

I often think about how an inanimate object can somehow be alive—how you can breathe life into an inanimate object—which is a very old sculptural idea. I think of my works as graves: they’re dead, but they remind you of having been alive.

The Tomb of Perneb is a completely inanimate stone that tells you how to act; it’s instructions. When you walk into the tomb, there is a wall with a depiction of Perneb and the people giving him objects. There’s a list in hieroglyphics of all of the offerings, almost like an Excel spreadsheet of what to bring. Above this scene, an abundance of pheasants and bulls and bread are illustrated, piled right up to the ceiling. The walls are packed. The tomb is like an animated film, conjuring what happened on that very site, in between the tomb’s walls.

In the next hallway, there’s a bizarre window and a figurative sculpture enclosed within a second room that you can’t get to. It’s a shock. There is one vitrine on the side that holds bowls and other objects that were found at the original site of the tomb. One of the very beautiful features about these bowls is how pedestrian they are. They were like the Styrofoam coffee cup of the time, but they speak so much about the hand that held them, the mouth that drank from them.

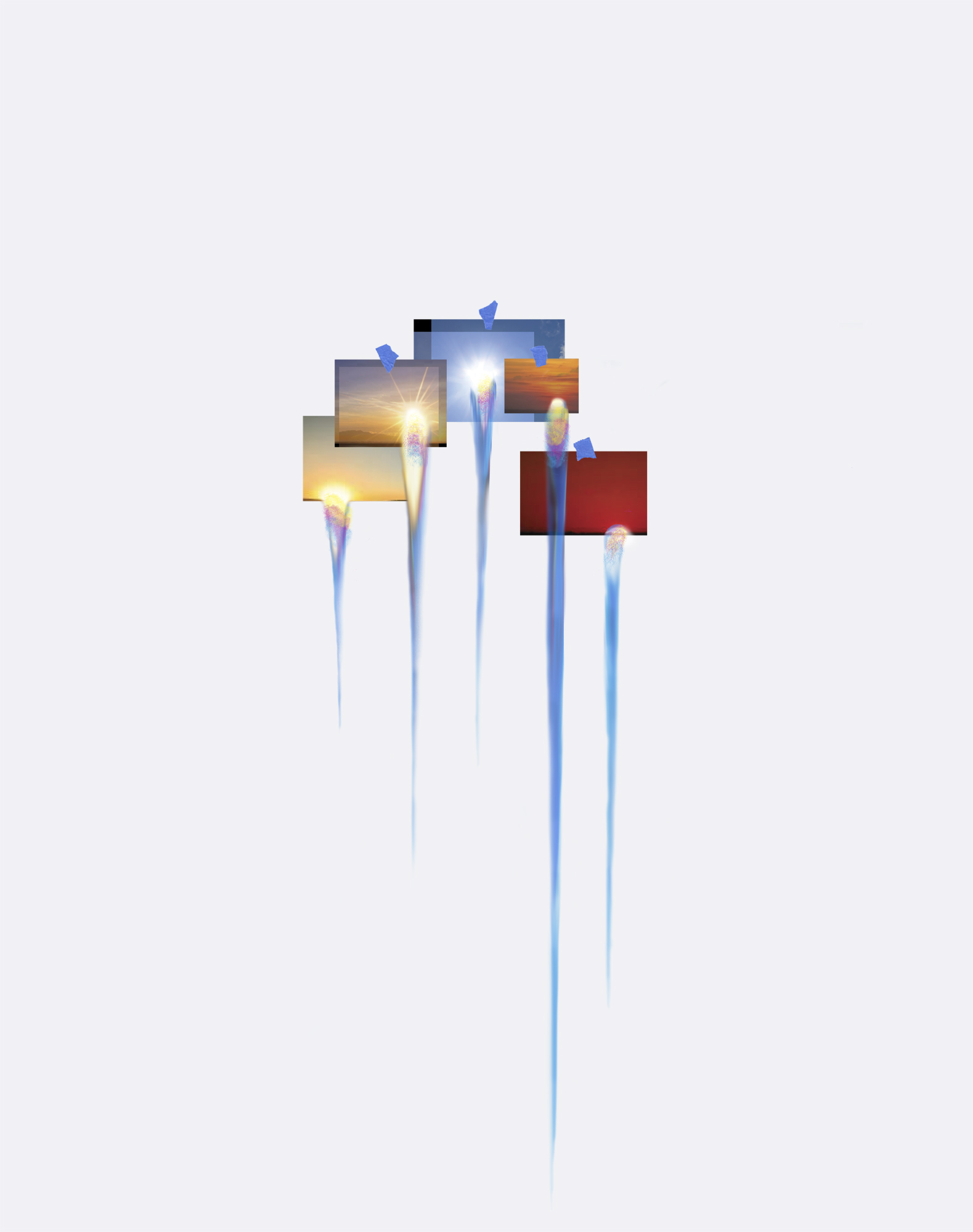

Sarah Sze's

Images in Debris

is available from Artspace for $1,200 or as low as $106/month

Sarah Sze's

Images in Debris

is available from Artspace for $1,200 or as low as $106/month

There’s also one little necklace. It’s not particularly valuable or beautiful or important, but the juxtaposition of the necklace’s delicacy with the majesty of the surrounding architectural structure and its incredible stones—which have lasted so long—makes you feel the fragility of even standing there, knowing that you won’t be standing there forever.

People come into this room and leave quite quickly. I think a lot of people panic, and it’s not just claustrophobia; it’s the intensity of the experience. You feel something alive there. That’s why you leave it so quickly. The architecture’s so tight it makes you aware that you are filling the negative space. You are somehow an object that’s being watched or is expected to perform.

Because it’s a grave, Perneb’s tomb self-consciously incites a conversation with a different place and a different time through the act of offering. I think it is very beautiful seeing this in the context of a museum because the idea of an offering is essential to any work of art. Artworks are really offerings from artists trying to contribute to a conversation that transcends their own lives.