You've heard the old idiom, you can't judge a book by its cover . Yet chances are, you've probably made a judgement about a stranger based solely on their appearance, perhaps without even realizing you've done it. Don't worry, you're not alone ( and we won't tell ), but it's important to recognize why we do this, despite countless evidence that stereotype-fueled assumptions lead to baseless judgements.

In her 1992-93 series Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say, London-based artist Gillian Wearing challenged the impulse to make assumptions about people before getting to know them, photographing over 500 portraits of strangers she met on the street. She prompted each individual to write whatever they pleased on a single white piece of paper; granting each person the opportunity to express themselves as something other than an image encountered and perceived by a viewer. These early works are a celebration the idiosyncrasies and nuances that make people who they are.

In this 1998 interview with curator Gregor Muir, excerpted from Phaidon's 1999 monograph, Gillian Wearing discusses finding inspiration in the complexities and intimacies of everyday life, the initial self-doubt that plagued her when she began working on Signs..., and how she thinks it will be received over time—and, the inherent madness inside of us all.

...

When you made the Signs ... photographs, how did people act when you approached them?

A lot of people told me to fuck off, especially in South London. The hardest thing about the Signs ... photographs was gaining people's attention. At first I felt a bit of an idiot approaching people with my clipboard and camera, but when people actually stopped and listened, they took it quite seriously. They thought it was a good idea and wanted to collaborate.

I was actually surprised that the

Signs ...

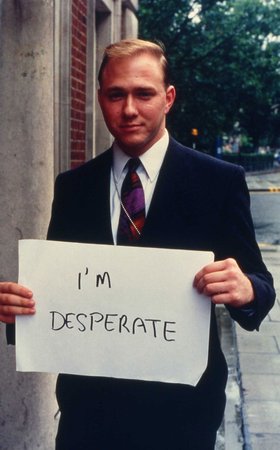

photographs worked out. People gave so much of themselves, which is unexpected in the British public, generally perceived as being reserved. Homeless people were the most generous. Some ended up writing stories about themselves which took up page after page, while the one-liners usually came from business people or people out shopping.

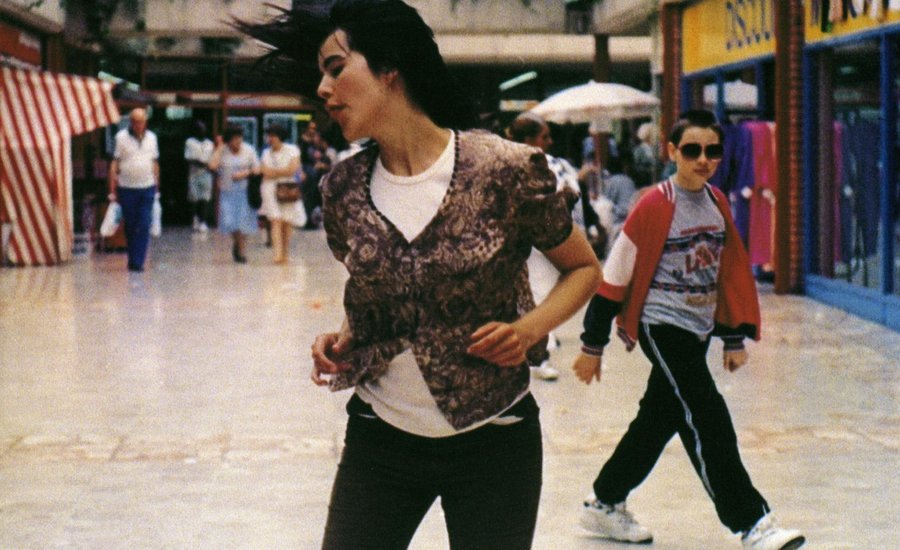

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else whats you to say, 1992-93

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else whats you to say, 1992-93

Tell me about the businessman who wrote 'I'm desperate'?

People are still surprised that someone in a suit could actually admit to anything, especially in the early 1990s, just after the crash. I literally had to chase him down the street. He only had time for one photograph and what he scrawled down was really spontaneous. I think he was actually shocked by what he had written, which suggests it must have been true. Then he got a bit angry, handed back the piece of paper, and stormed off.

Have you considered what Signs ... will look like in a hundred years?

Besides their nostalgic and anthropological value, I think the language will appear more violent. Especially the ones that say 'Fuck Off' or 'Fuck the Tories'.

Do you intend to take more Signs ... photographs?

I've been put off taking more, partly because people know what to expect.

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else whats you to say, 1992-93

Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else whats you to say, 1992-93

How do you think your work has changed since the

Signs ...

photographs?

Initially I wanted to find out what makes people tick. A great deal of my work is about questioning handed-down truths without being force-fed in front of the TV. I'm always trying to find ways of discovering things about people, and in the process discover more about myself. More recently, the work has undergone a shift of emphasis. Whereas before it was about asking people what they thought, I've started to produce scripted videos which are heavily structured.

Do you script everything now?

There are some things you can't ask of the public. For instance, the original idea for

Dancing in Peckham

stemmed from seeing this woman dancing wildly in the Royal Festival Hall. She was completely unaware that people were mocking her: either that, or she simply didn't care. Asking her to be in one of my videos would have been patronizing, so I decided to do it myself.

What inspires you to document people?

Years ago I used to be really impressed by fly-on-the-wall documentaries such as Franc Roddam and Paul Watson's The Family which was first screened in 1974 and followed the life of a working class family in Reading. Watching it for the first time I couldn't believe how revealing it was. The film crew, the presenter, and the whole Wilkins family were so naive in front of the camera. Brought to the screen, even the most normal scenarios suddenly seemed horrific. Everything about their lives was exposed. It was as if the whole thing were an experiment where no one knew what was going on. Nowadays, people get all nervous when you stick a camera up their nose. They want to look their best or come across as being witty and clever rather than just being themselves, which is far more interesting. I'm intrigued by nuances which aren't stereotyped yet. That's what I like about comedy: it reveals stereotypes which are right in front of your eyes.

2 into 1, 1997

2 into 1, 1997

How would you like to see documentaries being developed?

I get a real kick from documentaries that touch upon art as well as cinema. Recently I saw one about a South American football player, which was so well orchestrated it was as though he had colluded with the production company. At one point, they filmed him naked having a shower. His life was going downhill because he couldn't score any goals. It was so close to being a film, with hardly any narrative, just music. There was this beautiful footage where you just followed him around. That's where I would like to see documentaries go. Not just sitting someone in front of a camera and asking them to justify themselves, but actually approaching their life as though it were a more interesting concept.

Tell me about your work with the police force.

After Western Security - which had a fantasy element of dressing up and being an outlaw - I became interested in costumes such as police uniforms. Everyone has a relationship with the police. For instance, some people fear the law because they feel guilty of committing a crime.

My installation, Sixty Minute Silence , confronts the viewer with all these police officers in such a way that it's difficult to know where you stand. My own feelings, looking at them all, are that I'm half with them, half against. Clearly, it's hard to accept something that has an authority over your life, so I ended up using the police as ciphers to question how personal freedom is restricted.

The thing is, with the police you don't have to do much to them, because they're already loaded with significance. On the one hand they're merely civil servants, on the other they're synonymous with repression. Simply by using the police, people project much larger issues onto the work such as what's right and wrong, what constitutes acceptable social behavior, and so on. So the idea was to place these people, who normally control us, in a controlled situation.

Sixty minute silence, 1996

Sixty minute silence, 1996

At the end of the day, what kind of characters are you attracted to?

Being an artist, I have to go through life accepting certain situations and making a lot of compromises. I'm attracted to all sorts of people, average as well as extreme. But above all, I really love people who go through life without compromise and stick to their character, even when it means they remain unemployed, or they don't have any friends or relationships.

In a world which is willing to be elastic, they stick resolutely to this one path, this fixed belief in themselves. We all have a certain madness about us and these people don't mind showing it. Which leads me to believe that the most insane thing you can ever do is try to be sane.