Art history is littered with troubling instances of male artists objectifying women—from Andrew Wyeth only painting women he was "enamored" with and "smitten" by to Yves Klein using women's bodies as "living paintbrushes" for his

Anthropometry

series. By the end of the 1960s, female artists were fed up, determined to break free from the art world's oppressive structures and rigid gender roles. Some formed collectives, staged exhibitions in unlikely places, or simply made work about their own lived experience without apology, fear, or regret. In this excerpt from Phaidon's

Art and Feminism

compendium, scholar Peggy Phelan traces the history of second-wave

feminism in the art world

—and details how its problematic history should be rigorously debated, not simply celebrated or ignored.

* * *

The story is well known but it is useful to trace it again in broad outlines; complications in this very neat narrative will follow. In the 1960s, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and anti-war movements in the US, the student uprisings in Europe, and the intellectual and aesthetic stirrings of what has come to be called poststructuralism and Postmodernism, women woke up. Prompted by both Simone de Beauvoir’s cold-eyed claim in The Second Sex (published in France in 1949 and translated into English in 1953), that women are not born but made, and Betty Friedan’s analysis of ‘the problem that has no name’ in The Feminine Mystique (1963), women began conscious-raising groups in which collective conversations began to illuminate broader patterns in what had hitherto been understood as "personal stories" began to be interpreted as the logical consequences of larger political structures. Sensing the possibility of becoming emancipated from the burden of their personal particulars, women began to work together to protest against the ways in which political systems deformed women’s lives, aspirations, and dreams. Awakened, in short, to activism, feminists soon began to "talk back" to oppressive institutions and to create worlds more inclusive of the lives of women.

Artists were especially inspired by de Beauvoir’s analysis of “made” reality. If the lives of women were not the result of some intractable “natural law,” then they could be remade, revised, altered and improved. Such transformations would require imagination, determination, will: habits of mind well known to most artists. As feminists artists took up the tenets of women’s liberation, they found in it a rationale and inspiration for a new art practice. While the Civil Rights and anti-war movements in the US and the student movement in Europe had also inspired political awakenings, they had tended to employ art as a way of advertising their political arguments rather than as an arena for the visceral expression and exploration of those convictions. But for feminists, art became the arena for an enquiry into both political and personal revision; art was both extraordinarily responsive to political illumination and productive of it.

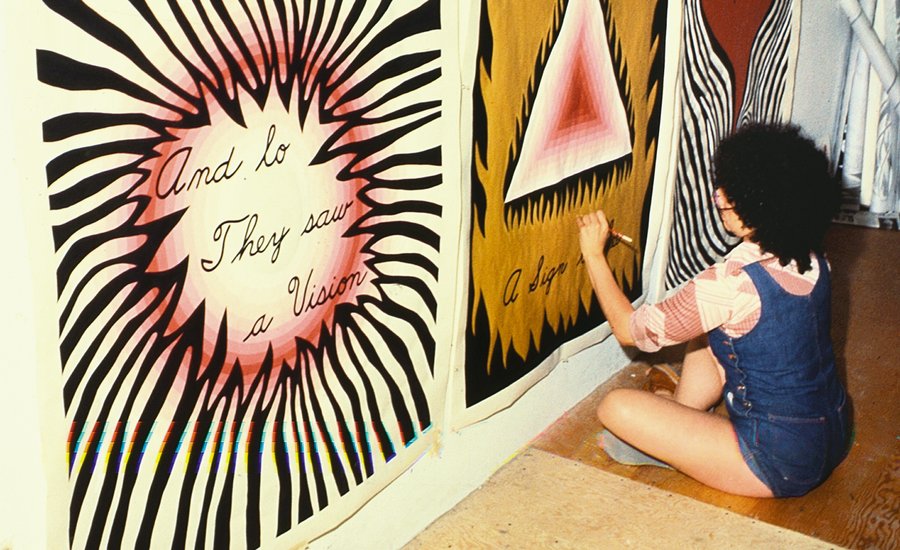

From protest at the lack of inclusion of women artists in galleries and museums, to resuscitation of the degraded languages of decorative and craft-based arts, the first phase of feminist art making was activist, passionate, and especially concerned with altering art history. Early achievements included the establishment of the Feminist Art Program by Judy Chicago, first at Fresno, California, in 1970, and then, with the collaboration of Miriam Schapiro, at Cal Arts in Valencia, California, in 1971. The first program devoted to the making of art by and about women, the Feminist Art Program also produced a well-publicized exhibition entitled

Womanhouse

in 1972. Organized by Faith Wilding, Schapiro, and Chicago, along with Feminists Art Program students, including the painter and theorist Mira Schor, twenty-four women refurbished a house in Los Angeles. Radically revising the line between public and private, the exhibition space was domestic space, and conventional assumptions about suitable artistic subject matter were discarded; the bathroom and the dollhouse were appropriated as “appropriate” exhibition spaces for feminist art.

Womanhouse

celebrated what has been considered trivial: cosmetics, tampons, linens, shower caps, and underwear became the material for high art. Covered extensively and often sensationally by the mainstream media, Womanhouse made it clear that there was a wide and passionate audience for feminist art.

Womanhouse (installation view) with works by Robin Weltsch, Vicki Hodgetts, and Wanda Westcoast

Womanhouse (installation view) with works by Robin Weltsch, Vicki Hodgetts, and Wanda Westcoast

Other students in the exhibition and Feminist Art Program, most notably Schor and Wilding, went on to have important and influential careers as artists. Schapiro and Chicago remained figures central to the development of feminist art in the US throughout the 1970s and most of the 1980s, especially on the West Coast. Additionally, the creation of The Women’s Building in Los Angeles in 1973 helped ensure and extend the work that Schapiro and Chicago had begun.

In New York, the inauguration of the women’s art co-operative A.I.R. (Artists-In-Residence) in 1972 provided an exhibition space for women’s work in the tumultuous art scene there. In addition to exhibiting work, A.I.R. also hosted a series of important talks that helped forge a language for feminist art that reflected the influence of the academy, the market, and the studio. Together all of these institutional efforts helped create a new space for the development of feminism and art.

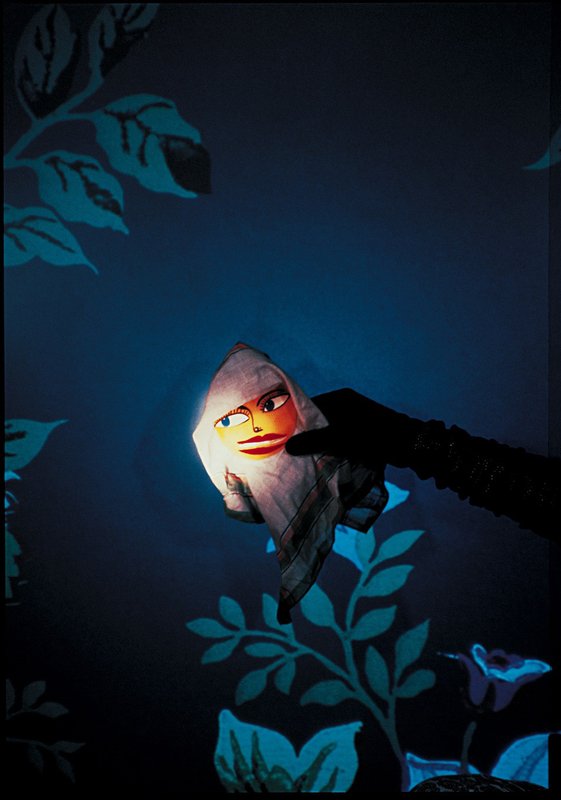

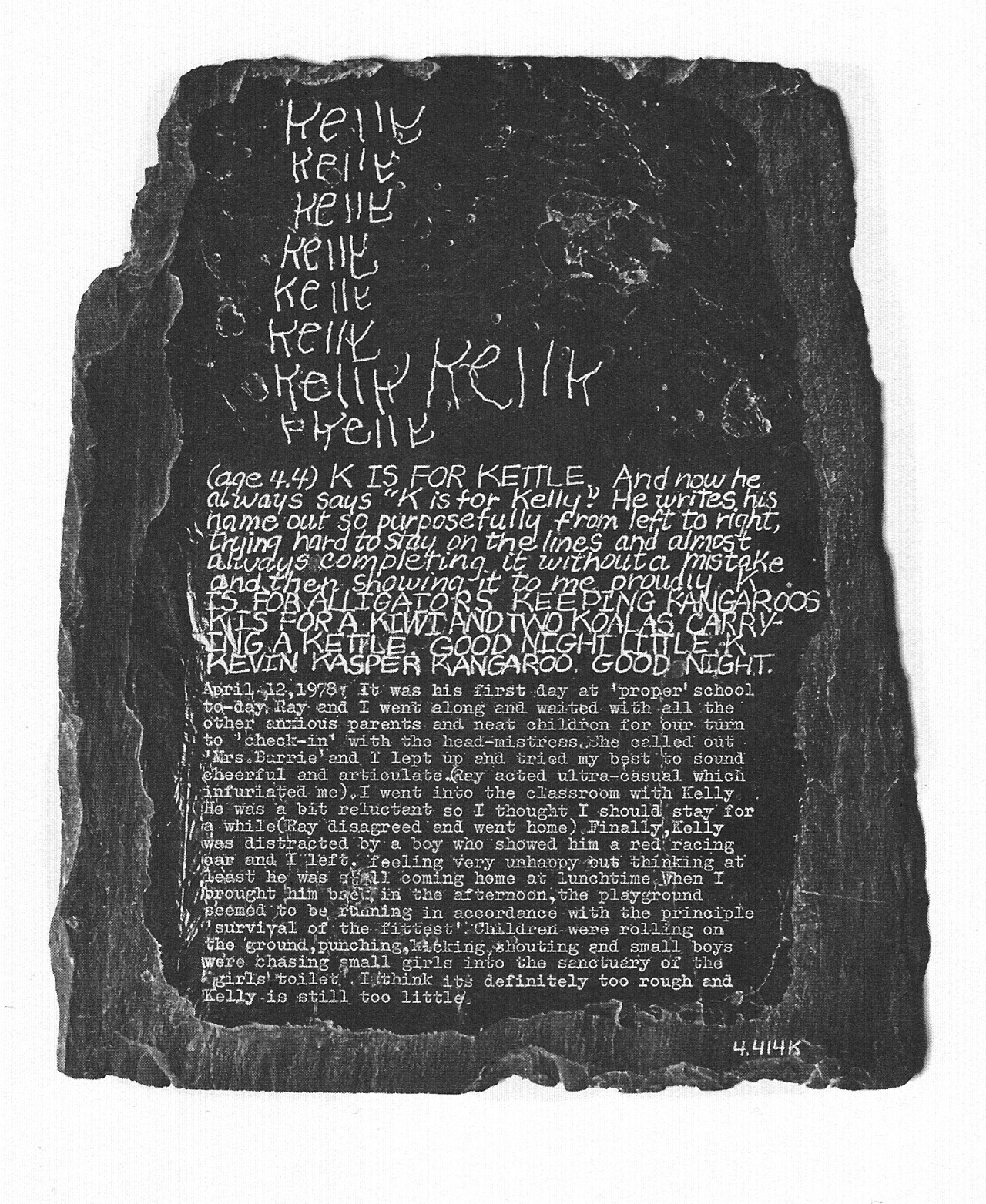

While much of the art that emerged from the feminist movement in the US in the late 1960s and early 1970s tended to focus on and make use of women’s bodies, the art that followed, much of which was created in Britain, tended to be rooted in debates about psychoanalysis and Marxism. The artist and theorist Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973-79) made a bid to shift feminist art making into an explicit conversation with Lacanian (and therefore necessarily Freudian) theories of sexual difference. Using her son’s diapers as visual traces of the continuity and discontinuity between mother/creator and child/object, Kelly’s installation created a space for a radical and intellectually rigorous interpretation of motherhood. In her extraordinarily influential 1973 essay (published in 1975) “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Laura Mulvey explicitly declares that she is employing “psychoanalysis as a political weapon.” Her work, like Kelly’s, is both theoretical and practical. Collaborating with Peter Wollen, Mulvey made a series of films advancing avant-garde film practice that intersected with strong and interesting work being done by feminist filmmakers in Europe, Britain, and the US. Experimenting with camera rotation, narrative deconstruction, and the fetishtic allure of the female screen star, films such as Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Mulvey and Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx (1976), Sally Potter’s Thriller (1979), Yvonne Rainer’s Journeys from Berlin/1971 (1979) and Margarethe von Trotta’s Marianne and Julianne (1980), made feminism a point of departure for far-reaching topics.

Mary Kelly,

Post-Partum Document

, 1973-79

Mary Kelly,

Post-Partum Document

, 1973-79

The early 1980s were dominated by the return of political conservatism in the form of Ronald Reagan’s government in the US and Margaret Thatcher’s in Britain. These stalled, if not completely halted, public funding for exhibition spaces, performance venues, and alternative presses that had been instrumental in the development of feminist work in previous years.

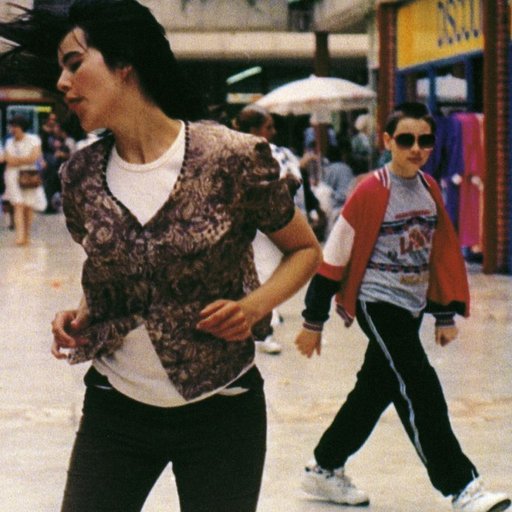

While the conservative turn was taking hold in mainstream politics, the dominance of white women within feminism, especially within academic feminist theory, began to be denounced as its own form of conservatism. In 1981, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color was published in the US. The anthology opened up the dialogue on race, which had been dominated by a binary model of racial difference (white and non-whites). A decade earlier, in 1971-72, significant exhibitons of the work of women of color had been mounted. Where We At: Black Women Artists was shown in New York in 1971 and included work by Faith Ringgold , Kay Brown, Pat Davis, Jerrolyn Crooks, Dindga McCannon and Mai Mai Leabua, among others. When AIR gallery and SOHO20 were founded, members said they were committed to eliminating both the sexism and racism characteristic of art galleries at the time. Howardena Pindell, an African-American feminist and original founder of AIR, eventually grew disenchanted with feminism’s persistent racism and helped organize an important 1980 show at AIR, Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the US. In the catalogue introduction, the Cuban-born artist Ana Mendieta flatly stated what many women of color had concluded after a decade of activism: “American feminism is basically a white middle class movement.”

Where We At: Black Women Artists participants, photographed by Pat Davis, 1971

Where We At: Black Women Artists participants, photographed by Pat Davis, 1971

A slightly more explicit, if not still exactly efficacious, attention to the issues of racial difference also began to be articulated more consistently in both discourse and exhibitions.

Mona Hatoum

,

Adrian Piper

, bell hooks,

Lorna Simpson

, Renée Green, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Coco Fusco and other theorist-artists explored the intertwining forces of racism and sexism. While Faith Ringgold, Michele Wallace, Judy Baca, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, and many others had insisted on this intersection from the earliest days of feminism, artists and theorists in the 1980s attempted to view race as something more than an “additional” category of difference to be appended to a list of qualifiers—class, gender, and racial differences’ as the litany often went. Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, a legal theorist and cultural critic, helpfully suggested that a concept of “intersectionality” might be employed as a way to understand the overlapping influences of racism and sexism. Moving away from the false choice of analyzing which was worse, Crenshaw’s insistence on the simultaneity of both sexism and racism also opened up ways to think about heterosexism, classism, ageism and other “isms” that continue to play a part in maintaining the status quo. This critique was at the center of much of feminist art criticism and theory in the 1990s.

Most people who write about feminism and art do so from a celebratory perspective. The few who do not are lamenting the face that high art lost its dignity (that is to say, some of its elitism) because of feminism. But thinking of the second phase of feminism as a traumatic awakening enables a more honest response to the history of violence and vilification that is woven into the legacy of the feminist art movement. Quite apart from the inevitable “personality conflicts” that dog any social and political group, the trauma that helped initiate the awakening of feminist consciousness was, in and of itself, wounding. Psychoanalysis reminds us that traumas produce distortions, repression, fictions of various sorts. Repressed traumas often inspire repetitions. Therefore, rather than sticking to the smooth narratives offered by either celebratory or denunciatory attitudes towards the history of feminism, it would be useful to develop the capacity to fashion a more complicated, indeed a more honestly ambivalent perspective upon this history. To think of the history of feminist awakening in terms of trauma might also help illuminate the strangely persistent fascination with art history as a discourse. Trauma is a break in the mind’s experience of time. History writing seems to promise a way to suture events that might initially appear to be ruptures.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The Secret of Ana Mendieta's Mystical Cave Women

10 Women Artists Who Made History

Mona Hatoum on Art as Resistance

5 Women Artists Redefining Feminist "Body Art" at NADA