Mexico City is abuzz these days, a scene centered around an increasing network of artist-run galleries and experimental spaces, the Material Art Fair, and SOMA—an artist-founded school offering two-year masters programs with a who's-who roster of emerging and established artists. The scene in Mexico has exploded as social media has empowered global, internet-based practices, and three of those artists who entered the global stage with it—Abragam Cruzvillegas, Gabriel Kuri, and Damián Ortega, all students of Gabriel Orozco in an informal workshop—are featured below. Drawing from Phaidon'sVitamin 3D, a compendium of all the emerging and contemporary sculptors you need to know, we've featured three of Mexico's rising art stars below.

ABRAHAM CRUZVILLEGAS

Born 1968, Mexico City, Mexico. Lives and works in Paris and Mexico City.

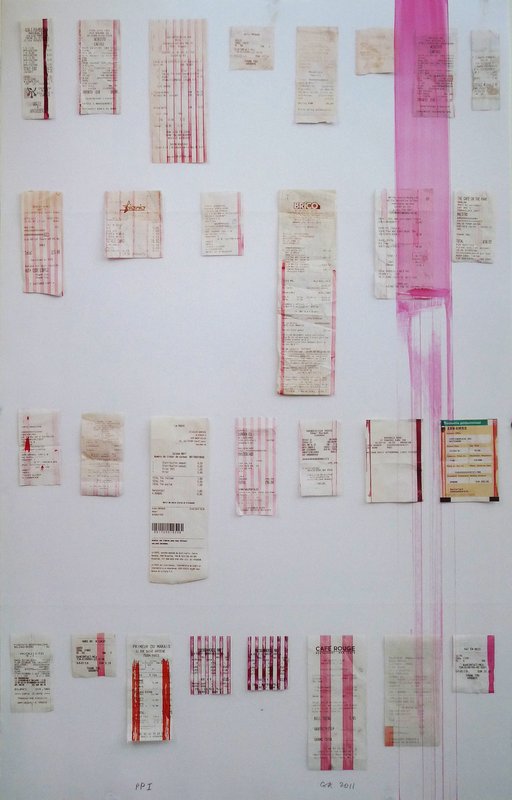

Aeropuerto Alterno, 2002

Aeropuerto Alterno, 2002

The Mexican-born artist Abraham Cruzvillegas follows a particular Latin American artistic trajectory in which a strong traditional craft sensibility and the tendency to reuse everyday objects is combined with the (Western) idea of the readymade. At first glance his works may recall pieces by his fellow Mexican artists Damián Ortega and Gabriel Kuri, but the severe play of forms, shapes, and colors in his sculptures and installations, as well as their strong autobiographical and political references, distinguish them from those of his compatriots.

Cruzvillegas immersed himself in both fine arts and philosophy during his years at the University of Mexico (UNAM), and his dual interests are apparent in many of his pieces, which explore at their core the ideology of the object and the economic structure of Western society. Often stunningly handsome, they play with the idea of how we are seduced by beauty, only to break this fragile notion by juxtaposing it with something ugly and seemingly deformed. By appropriating everyday items and altering them, Cruzvillegas advocates a non-elitist approach to art-making and creates relationships between numerous—often seemingly contradictory—aspects of modern life. He often conserves the primary function of the objects he is using, relentlessly bringing them back to their cultural and utilitarian origins. A keen observer of the world around him, he uses everything from knives and plants to fish hooks, feathers, newspapers, candles, ropes, and nails. He once even incorporated the jaw of a shark into an artwork.

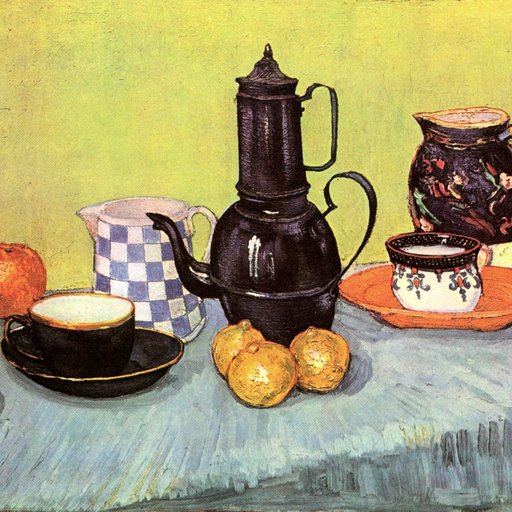

Canon enigmatico a 108 voces, 2005

Canon enigmatico a 108 voces, 2005

Though he is still an emerging artist, Cruzvillegas has been working in this field for more than a decade, beginning with appropriations of folk art made by his father. He gained a wider audience at the beginning of this decade during a boom of exhibitions focusing on the younger generation of Mexican artists. Aeropuerto Alterno (2002) shown at the 2003 Venice Biennial, became one of his trademark works. It consists of a handmade butcher’s block into which the artist has stuck two dozen or so used knives of all sizes and shapes. The title suggests that the knives have flown in from different places to land in the wooden structure. Their arrangement also gives the impression of a floral bouquet.

A more recent work is Canon enigmatico a 108 voces (2005), in which the Spanish word canon takes on a dual meaning (“cannon” and “canon”). It is comprised of 108 buoys found on the beach in Mexico, strung together and suspended from the ceiling like grapes on a vine. The play of shapes and colors inspires the viewer to contemplate faraway, exotic Mexican beaches. As in many of Cruzvillegas’s works, the objects he uses are relentlessly utilitarian and mass-produced, yet somehow transformed so that they seem as if they were made exclusively for his works.

– Jens Hoffmann

GABRIEL KURI

Born 1970, Mexico City, Mexico. Lives and works in Brussels and Mexico City.

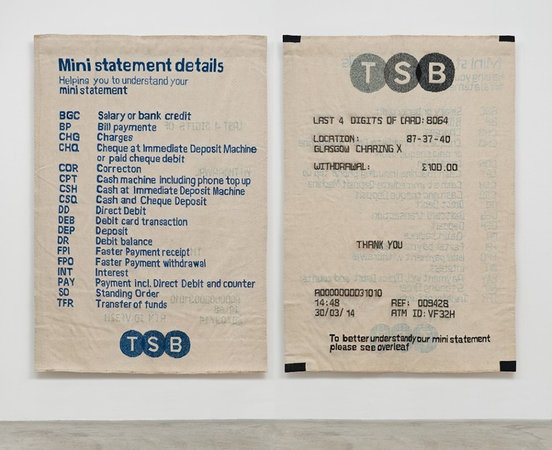

untitled tsb mini statement details, 2014

untitled tsb mini statement details, 2014

Gabriel Kuri studied in Mexico City and London but is now based in Brussels. From 1987–91 he was active in an informal school run by the artist Gabriel Orozco that included Damian Ortega and Abraham Cruzvillegas. Known for his works made from altered commercial products, such as redesigned Kellogg’s Corn Flakes containers, Kuri is also concerned with the import and export of culture, wealth, and identity. He focuses frequently on the life of products that are manufactured in Mexico by US companies only to be re-imported as authentically “American.” Orozco has used the term “poetical activist” for Kuri’s obliquely critical work.

His tapestry, Untitled Leaflet Gobelin (2002), mimics the process of production that characterizes contemporary economics but reinscribes a surprising value where normally we would expect to find none. Cheap advertising leaflets with a brief life were used as a cartoon to design the tapestry, ensuring a lasting life for the simple layout. Though no conscious reference is made, the labour in this work begs comparison with Alighieri e Boetti’s Afghani-made wall hangings from the 1970s and a particular production of meaning through translation.

Two nudes two points, 2013

Two nudes two points, 2013

Untitled (2006) similarly involves a transformation of materials. Two cans poke out from the dismantled six sides of a cube, made of painted plywood and weatherproofed with roofing tar roll, again Arte Povera precedents come to mind. There is a Surrealist’s affection for the unexpected encounter, the hybrid creation of montage and the transformation enabled by shifts in scale or focus in this work. There is even a palpable discomfort in examining some of Kuri’s juxtapositions; things are out of place. Not all of his improbable combinations are constructed, however, and even those that are fabrications often suggest the kind of naturally occurring event or chance incident that we might stumble across in everyday life or create ourselves in the semi-conscious process of doodling. An apparently spotted tree trunk photographed by Kuri, for example, turns out to be a public dumping ground for chewing gum. Surprisingly, the random accumulation of gum has an unexpected beauty to it, as does the idea of the habitual behavior that resulted in this sculptural form. What may have been one person’s unthinking action has taken on a collective aspect, each individual adding independently to this collaborative effort.

Reflecting on the strategies of Arte Povera and Surrealism, Kuri’s work is a fascinating example of the way in which contemporary artists continue to draw on art-historical models. Many of his works not only encompass such historic resonances but also express the artist’s interest in the interplay between commerce and art. Similarly, a recent sculpture presented as part of the exhibition “Model for a Victory Parade” (2008) comprises a simple conveyor belt with a squashed energy-drink can stuck at one end, perpetually tumbling in a frustrated attempt to ‘check out’. This debris of an imagined ceremony, while holding multiple connotations, emphasizes the politics of energy consumption and, like much of Kuri’s work, questions our own complicity in the production of events.

– Jens Hoffmann

DAMIÁN ORTEGA

Born 1967, Mexico City, Mexico. Lives and works in Berlin and Mexico City.

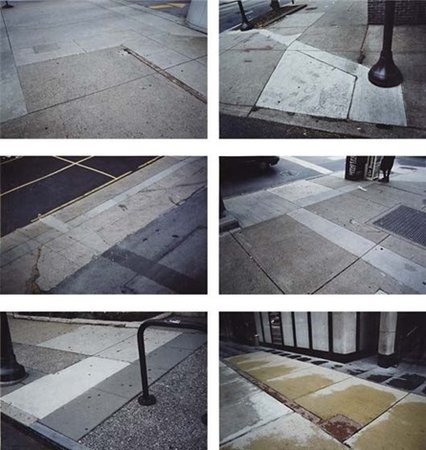

Composición Concreta, 2002

Composición Concreta, 2002

The work of Damián Ortega is in many ways indebted to the Brazilian neo-Concrete movement, which in the late 1950s and early 1960s sought to infuse a free, experimental spirit into the rigid dogmas and abstract geometry of Concretism, reaching out to more subjective and expressive manifestations and, above all, life itself. Ortega’s Composición Concreta (Concrete Composition, 2002) is a group of six photographs of different sections of concrete sidewalks that have been laid out and precariously patched up in geometric patterns of white, grey, and brown. They contain very little of Concretism’s rigidity and rigor in the geometry, and abstraction is an oblique reference – after all, there is nothing more figurative and impure than the dirty city streets portrayed here. In 2004–06 Ortega made a second group of works departing from these photographs: Mampara – Composición concreta I–VI (Screen – Concrete Composition I–VI), made, not insignificantly, to be exhibited in São Paulo, the birth of Brazilian Concretism. Each Mampara replicates the geometric design found in the sidewalk photographs, transforming them into folding concrete geometric screens that recall the sculpture of Neoconcrete artist Franz Weissmann.

Ordem Réplica e Acaso (Order, Replica, and Chance, 2004) establishes similar plays between photography and sculpture, this time also connecting geometric abstraction with architecture. At the Museu de Arte da Pampulha, a former casino designed by Oscar Niemeyer in Belo Horizonte, Ortega created a series of twenty-four cubes, each made up of eight smaller articulated cubes connected by metal hinges and together forming a 60 cm cube. The faces of the smaller cubes have the same bronze color, reflective surface and dimensions as the mirrored tiles covering the museum’s main wall. As in Composición Concreta and Mampara, Ortega submits a flat, real-life object to a process of abstraction in order to render it in three-dimensions. In appropriating Niemeyer, Ortega also references Lygia Clark, a Belo Horizonte native, and her famous series of Bichos, abstract geometric sculptures made up of articulated aluminum sheets joined by hinges. The photographic component of Ortega's work consists of a triptych (a module often used by Ortega) showing three possible configurations of all the twenty-four cubes in the space of the casino: as a giant cube, as a straight line duplicated in the mirrored wall, and a sinuous Niemeyer-like line, respectively signifying order, replica and chance.

Spiral of Violence, 2005

Spiral of Violence, 2005

A similarly experimental approach to abstract geometry also informs Ortega’s Spiral of Violence (2005). The work consists of a sixteen-panel window frame and its sixteen corresponding glass panels, all deconstructed and suspended in mid-air. Each glass panel has been marked by four intersecting horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines, its composition suggesting the British flag (a small sticker of the flag is found on one of the panels), which bear the traces of physical violence. One can consider this work an investigation into the possibilities of the smashed and transparent geometric plane, and in circling the suspended sculptural work one may be reminded of Helio Oiticica’s 1960 series Relevos Espaciais (Spatial Reliefs). The same sculptural suspension is found in other, more figurative works by Ortega, such as Cosmic Thing (2002) and Miraculo Italiano (2005). In Spiral of Violence, however, the geometric sculptural demonstration is imbued with violent, political tones, another lesson that Ortega may have learned from Oiticica.

–Adriano Pedrosa