You might think you know a little something about Sandro Botticelli : his life in 15th-century Florence, the patronage of the infamous Medici clan, his seminal paintings including The Birth of Venus and Primavera of postcard and novelty-mug fame. There is, of course, much more to the early Renaissance painter than this simple story lets on; did you know, for instance, that his birth name was in fact Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi? We thought not. In this excerpt from Phaidon’s monograph Botticelli , we delve into the painter’s lesser-known works in search of mythical and mystical allusions, historical and artistic references, hidden self-portraits, and more, all rendered in an approach thats wholly his own. Fans of classical painting, this is what you’ve been waiting for.

FORTITUDE , 1470

Fortitude is the earliest documented painting by Botticelli and belongs to a series of the “Seven Virtues” painted in 1470 for the Tribunale di Mercancia, the commercial court of Florence housed in the Palazzo Vecchio. Piero Pollaiuolo (c.1441–96) painted six of the panels (also now in the Uffizi); this is the seventh. The paintings of the Virtues were originally set into the panelling above the bench on which the six magistrates of the court sat. The perspective of the pictures allows for the fact that they were intended to be hung high, with their tops about 3.5 m (12 ft) above the floor; this is why the throne in this painting seems to fall back. The influence of Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–88) can be seen, particularly in the drawing of the armor.

THE ADORATION OF THE MAGI , c.1475

Guasparre Lami, a Florentine merchant, commissioned this Adoration for his chapel in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The third figure from the left in the foreground has been suggested as a portrait of Lami. Among the groups of spectators Botticelli has portrayed several members of the Medici family, and since the time of Vasari efforts have been made to identify them. The figure kneeling before the Virgin is Cosimo de’ Medici. The group on the right includes Giuliano (in profile) and, below the Virgin, Piero, the father of Lorenzo the Magnificent. The two at the far left have been said to be portraits of Lorenzo the Magnificent and Poliziano. Some of the portraits are certainly posthumous. The figure in the yellow cloak at the far right is generally regarded as a self-portrait of Botticelli. The original marble frame of the picture is now lost, and the painting has been cut at both sides; a narrow strip is also missing at the top.

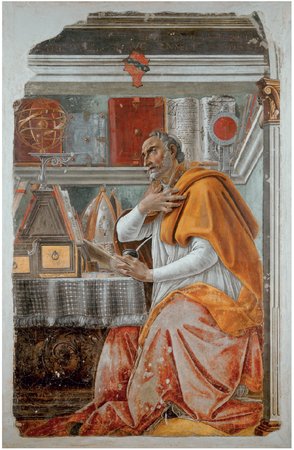

SAINT AUGUSTINE IN HIS CELL , 1480

The Vespucci family, whose escutcheon can be observed above the saint’s head, probably commissioned this fresco for the church of Ognissanti as a partner to the fresco Saint Jerome in his Study (1480), by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448/9–94). Augustine (AD 354–430), Bishop of Hippo Regius (today Annaba, Algeria), was a philosopher and theologian who had a profound influence on the development of Christianity. The books and instruments shown here are emblematic of learned pursuits, but it is the clock above his head that ties the fresco to that of Ghirlandaio.

The clock points to the hours 1 and XXIV, suggesting the hour of sunset. In his writings Augustine describes how he was one day working in his study just before sunset, when he received a vision of Saint Jerome at the very moment of the latter’s death and ascension to heaven. Augustine’s right hand is pressed to his breast in pious awe, and the deftly expressed lines on his forehead suggest both surprise and wonder. This is the earliest surviving fresco by Botticelli and is much damaged. The theme of Saint Augustine is one that Botticelli returned to later in his career when under the influence of the monk Girolamo Savonarola.

PALLAS AND THE CENTAUR , c.1482

Painted for Lorenzo and Giovanni di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici (cousins of Lorenzo the Magnificent), this allegorical scene probably represents the victory of reason (as represented by Pallas Athene—the Roman Minerva—goddess of Wisdom) over sensuality (the lustful, nymph-chasing centaur). However, this interpretation fails to explain such unusual details as the goddess’ large halberd (her long-handled axe), the centaur’s bow, or the fence on the seashore. Pallas’ dress is embroidered with interlocking diamond rings, the emblem of Lorenzo de’ Medici, and it has been suggested that an homage to him is concealed in this allegory.

VIRGIN AND CHILD ENTHRONED , 1484–85

In this compelling altarpiece Mary appears to be opening her dress to breastfeed the Christ Child. She is flanked by John the Evangelist to her right; the gaunt form of John the Baptist on the left, patron saint of Florence, gestures towards the Virgin and Child. Instead of architecture, Botticelli employs a natural background in which palm fronds and leaves are woven into niche-like structures surrounding the Virgin and saints. This picture was originally painted for the wealthy Florentine banker Giovanni de’ Bardi for his chapel in the church of Santo Spirito in Florence. Payment for the frame was made to Giuliano da Sangallo in February 1485, and Botticelli was paid six months later for the painting.

VENUS AND MARS , c.1485

This picture was probably painted for a member of the Vespucci family, whose emblem of wasps (vespe in Italian) appears above the head of Mars, the God of War—although the insects could simply represent the “sting” of love. Mars is portrayed sleeping, and he may even be indulging in the deep post-coital sleep described as the “little death.” His lover, Venus, goddess of Love and Beauty, watches him placidly, while small satyrs—half-men, half-goats—frolic and tease the unarmed god. They steal his lance to poke an angry wasps’ nest, blow a conch in his ear and stick their tongues out lewdly towards Venus. The meaning of the allegory can be summed up as “when love is awake, discord sleeps” (or, indeed, “love conquers all”).

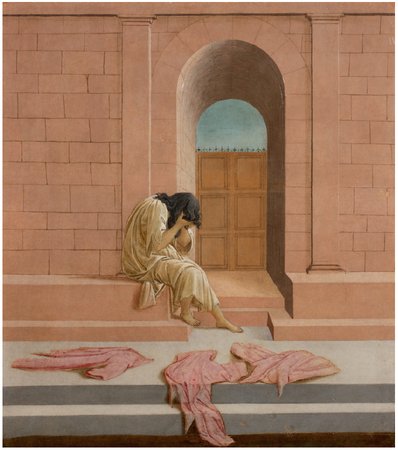

THE DERELICT , c.1490

This is a painting of supreme mystery and symbolism, probably of Biblical inspiration: Ammon driving away Tamar. Adolfo Venturi (1856–1941) noted: “The closed door inside the grey wall, the veiled woman in her black casque of hair are surrounded by the same irresistible suggestion of mystery. The desperate sobs of the abandoned one resound in the deep cavity of the gate, breaking against the closed door, which will never open.” The painting has been variously attributed to Masaccio, the studio of Botticelli, and Filippino Lippi.

DANTE’S DIVINA COMMEDIA INFERNO XXXI , 1492-97

An edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, with a commentary by Cristoforo Landino and nineteen engravings to illustrate the first nineteen cantos of the Inferno, was published in 1481 in Florence. These illustrations, which had been engraved with indifferent success in the workshop of Baccio Baldini, were taken from drawings by Botticelli. He illustrated only nineteen of the one hundred cantos, leaving the work unfinished when he went to Rome to work on the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel. More than ten years later, he began once more to illustrate the Divine Comedy, intending to provide a drawing for each canto. Ninety-three of Botticelli’s illustrations are still extant, eighty-five in Berlin and eight in the Vatican Library.

In Canto IX of Inferno, Dante and his guide in the underworld, the Roman poet Virgil, encounter a host of demons and lost souls as they approach the Gate of Dis. A messenger from Heaven scatters the demons as he flies across the river Styx and demands that the gate be opened for the travelers. Virgil and Dante pass through and enter the Sixth Circle of Hell. Canto XXXI of Inferno sees Dante and Virgil meeting the giant Ephialtes, who is in chains with his arms bent behind him in punishment for challenging the gods. Canto I of Paradiso depicts Dante, having vanquished Lucifer, rescued his love Beatrice and escaped Purgatory, flying towards Heaven with Beatrice at his side.

MYSTIC NATIVITY , 1500

The Mystic Nativity was probably painted as a private devotional work for a Florentine patron. In the foreground, angels embrace virtuous men in celebration of the birth of Christ, while above them a heavenly circle of angels dance and sing in praise. Between them, in the middle section, the wise men and shepherds flank the holy family in the stable. The picture is known as the Mystic Nativity because of the combination of symbols alluding both to Christ’s birth and the Second Coming, his return to Earth as described in the apocalyptic Book of Revelation. Demons, for example, are seen in the foreground scurrying back to the underworld.

The picture was painted at the turn of the century, a period that prompted many prophesies concerning the end of the world. The Greek inscription at the top reads: “I, Sandro, painted this picture at the end of the year 1500 during the tribulations of Italy in the half time after the time, in accordance with the eleventh chapter of Saint John in the second woe of the Apocalypse, during the unchaining of the devil for three and a half years; then he will be fettered in accordance with the twelfth chapter, as here.” This is the only painting by Botticelli that is both signed and dated. The year traditionally began in Florence on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation. “At the end of the year 1500” means, therefore, March 1501 in the modern calendar, a time when Florence was afflicted by war, the plague, and internal troubles. The inscription, which has been interpreted repeatedly, cannot be proved to refer to the execution of Savonarola and his two companions in 1498. The “tribulations of Italy” may refer, as has been often suggested, to the invasion of northern Italy by Cesare Borgia and his French troops.

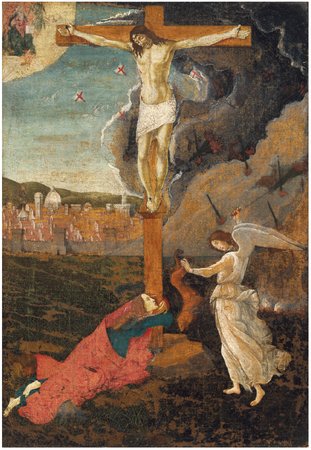

MYSTIC CRUCIFIXION, c.1500

The Mystic Crucifixion echoes religious symbolism similar to that seen in the Mystic Nativity and displays Botticelli’s belief in an apocalyptic Second Coming of Christ. The heavily damaged work shows the prosperous city of Florence facing a raging biblical storm, with the two sides of the composition divided by the Holy Cross. The kneeling Mary Magdalene embodies penitence, reaching out to an angel who beats a lion, symbol of Florence.

At the time of painting, the city was wracked by war, plague, and political infighting. Botticelli and many of his fellow Florentines had also been influenced some years before by the apocalyptic preachings of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola (1452–98), who criticized the indulgences of both Church and state, and prophesied a terrible cleansing flood that would bring reform. Savonarola had also criticized the pagan and self-serving nature of much Florentine art and culture, leading to the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497, when his supporters burnt thousands of books and artworks in the streets. Having angered Pope Alexander VI, Savonarola was executed with two of his followers in 1498.