As a Chinese citizen who came of age in the 1980s and ‘90s, Yin Xiuzhen learned early on the value of managing contradictions and the dissonances they leave in their wake. Growing up in Beijing, she saw modernity and tradition, local and global, East and West, state control and individual self-expression all combine, morph, and compete for dominance, resulting in the sometimes-dizzying reality of contemporary China. Of course, the ability to synthesize disparate elements into a discrete, meaningful form is at the essence of art making. Yin wields this power with a deft hand in her work in installation and sculpture, using everyday materials (clothing and concrete are particular favorites) to tell new stories about the forces shaping our societies today, including especially globalization and notions of progress as well as the social and environmental degradation those powers can engender.

She’s now one of China’s best-known contemporary artists and a regular of the international biennial circuit, in addition to solo shows at top-tier venues around the world including Pace Gallery , the Groninger Museum , and the Museum of Modern Art . In this interview with the curator and critic Hou Hanru excerpted from Phaidon’s monograph Yin Xiuzhen , Yin discusses how smog, terrorism, and the pleasures of eating with friends all come to inform her multifaceted approach to art.

HOU HANRU: You’ve been one of the most prolific artists since the 1990s, not only in China but amongst your generation as a whole. When looking at your works, we can see the great changes that have taken place in Chinese culture over the past twenty to thirty years. They’re like a record, a process of reflection, or more precisely, an individual’s unique observations and annotations on these changes. I’d like to begin by looking back at your first work as an artist. Where did you begin?

YIN XIUZHEN: When I was at primary school, I got into painting under the influence of my older sister. She was of the generation sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, and enjoyed artistic paper-cutting, painting, and reading. I once went to visit her at her production site in the countryside. The golden wheat fields and her walls covered in paintings struck a deep chord in me, and I began to grow obsessed with painting. I wanted to become a painter who could depict nature.

In high school, I was put on the maths and sciences track. The education at the time divided the sciences from the humanities. This was a flaw in the education system, which hindered the well-rounded development of children. After graduation, I didn’t pass the test to get into a science school, and so I became what they called a “youth awaiting employment.” After waiting for a while, I got a chance to take part in an amateur art class. Only later did I discover that I could take a test to get into an art academy, but I’d have to take tests on the other “humanities”too. Those were my busiest days. I felt that since I’d graduated, I was an adult, and I should never ask my family for money again. I spent every day as a temp worker on construction sites, working as an interior painter, and I’d use the money I earned to pay for remedial night classes for the humanities tests. Then, at weekends, I’d attend art classes. In 1985, I was accepted into a university oil-painting department.

Beijing Normal University, right?

At the time it was called the Beijing Normal Academy. It later changed to Capital Normal University. Their art program back then was very conservative, mainly consisting of Soviet School painting techniques and Socialist Realism. But out in society, the ’85 Art New Wave Movement had begun, and it shook our stilted classrooms. There was also the Robert Rauschenberg exhibition at the National Art Museum. This had a great impact on us – the fact that you could make art in this way. It was fun. We were basically just messing around in those days, trying to do things in a different way. Our class was very active, with all of us trying out all kinds of things in art, but we had no encouragement from the school. Song Dong and I supported each other. It was difficult, but there was so much joy in creation. After graduation, I taught painting at the Middle School attached to the Central Academy of Industrial Art and Design for ten years, but I also began my artistic career.

You’d already begun to break out of the bounds of traditional oil painting, and had certain leanings towards conceptual and installation art. That was in the early 1990s?

Yes, basically from 1992 on, I started painting less and less. I’d graduated in 1989. That was an abnormal year. The “China/Avant-Garde Exhibition” held at the National Art Museum at the beginning of the year was the closing act of the ’85 Art New Wave. Then, after the June 4 incident in Tiananmen Square, it was as if everything ground to a halt. The air was suffocating. It wasn’t until 1992 that a few scattered contemporary art events started springing up, but they were all underground. That was also the year Song Dong and I got married. We’d borrowed a video camera for the wedding, and were supposed to return it that night. Dong shot his first video artwork, Frying Water , on our wedding day. This work has never been exhibited. The conditions for contemporary art were very poor in those days. News of art events was spread only by word of mouth among friends. My painting at the time was becoming more conceptual. I wanted to express the divisions between people, as well as the relationship between individual experience and contemporary life, but I found that the language of painting was unable to convey these perceptions, and so I experimented with certain spatial artworks connected to the environment. The use of objects to express sentiments felt direct and exciting. It was like a taste of freedom. I began working off-canvas, in installation and performance art, in 1994. There were a lot of avant-garde contemporary art exhibitions and events at the time, and the atmosphere was electric. Though most of it was underground, and many of the events were shut down as soon as they began, this passion for new art couldn’t be contained.

This was a direct reflection of the changes taking place across society. For instance, the modernization of Beijing was taking off: old houses were being demolished and new construction was happening on a massive scale. This affected the lives of many people, especially Beijing natives, those traditional families who’d been living in the city center for so many generations. Their peaceful lives were suddenly shattered. This is vividly reflected in your works. You depict these changes on a very personal level.

Yes. That’s why I made Ruined City . It was around that time. Then there was Change in 1997. Things changed so fast in that year. It was all around you, visible every day. I’d ride my bike to work in the morning, and the old houses would still be there, but on my way back in the afternoon, they’d be gone. It was like this for a lot of neighborhoods. The old houses were constantly being knocked down, old memories ripped out, culture torn away. The homes and ways of life that had stood for centuries were destroyed for a quick profit. The peaceful coexistence of neighbors was disrupted by this illogical, blind “modernization.” It was like a big family before. Though there was conflict, the neighbors had a kind of energy between them that was able to melt away these conflicts, but that energy was wiped out by the energy of “profit.” A lot of people were forced, while others welcomed the change. Intellectuals were sad and angry when they saw this ancient capital, the result of eight centuries of civilization, suddenly swept away. The short sightedness of the government and the masses catalyzed this irreversible tragedy. The common people wanted change. Even though life in the big courtyards was like having one big family, there were a lot of inconveniences as well, such as keeping warm in the winter and the use of communal bathrooms. They needed modernization, but they didn’t know what it really meant. They moved out willingly in the name of modernization, but were forced to live way out in the outskirts.

Far from the city.

Far from the city, far from their own history and culture, far from friends and family, far from close interpersonal relations. Work became yet another inconvenience. It brought about the rise of the rush hour, that time of mass worker migration between outskirts and city, and those “modernized” homes became isolated bedrooms. This man-made congestion, chaos, and isolation was the result of the idiocy and ignorance of policymakers, and it took place under the controlling interests of the rich and powerful.

It led to today’s never-ending expansion of the cities.

They grow with no end in sight, bringing traffic congestion, poor air quality, and a higher cost of living. But we’ve paid an even greater social price, a painful price, wasting the health of generations.

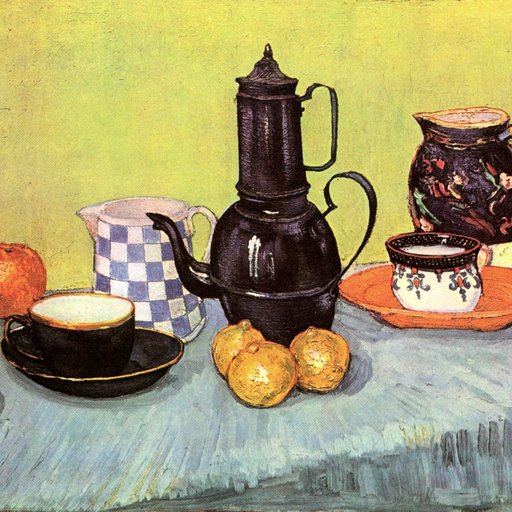

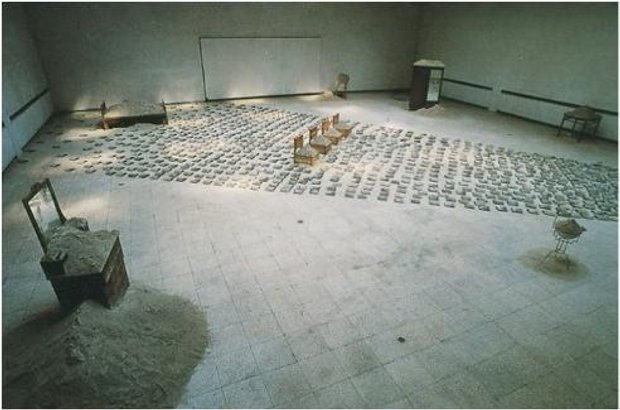

Ruined City

, 1996

Ruined City

, 1996

It’s a problem with the entire plan: this approach to development is highly focused on short-term gain. It assumes that expansion means development and that development means a better life in the future. But it’s actually brought great inconvenience to our lives, another kind of inconvenience.

Amidst the great changes taking place in the external appearance of our lives, our memories are being slowly whittled away, as is our culture. It’s very frightening. Once you lose these things, you’ll never get them back. This old city has given wisdom and experience to so many generations of young people, and it should continue to provide our society with energy, but the great demolition drive made us lose our connection and roots in this essence of the past. I’m not saying I don’t want development, but wise development and blind development aren’t the same thing. At the time, they demolished a lot of important buildings and neighborhoods, and now, for tourism, they’ve built a lot of fake antiques. But what they demolished wasn’t just an outward appearance—it was the hearts of people, even the conscience of people. This demolition and construction is a marker of a deeper level of human understanding and values. In those days, we felt it was a shame, but we felt helpless as well. We had no power to preserve these precious things and experiences, and so we could only use artistic methods to describe this sadness and indignation, to shout it out.

How did you choose those methods? For instance, in Ruined City , you collected the materials left over from a demolished building, and turned them into an installation expressing the memories of a lost city. How did you come up with the idea of using readymade materials, rather than just painting or making a sculpture?

When all of society becomes materials, other materials and methods begin to look inadequate. When you take the rubble directly into the works, these materials, with their experiences and histories, can “speak” for themselves. They have individual and collective memories, as well as many traces of life. When these materials emerge in a different environment, a vein between true reality and the artwork forms. It formalizes real life and allows the objects to speak, to have their own voice.

There were also many layers of meaning in the exhibition setting at the time.

The exhibition setting was the Capital Normal University Art Museum, because there were few places where you could hold such exhibitions then. We talked it over with our teacher Yuan Guang. We all got along quite well. He was the director of our art museum, and he supported me. He said I could use this facility. The exhibition only ran for a few days. He’d set up a series of solo exhibitions called “Individual Methods” and Ruined City was one of them. I found some of the materials among the demolition rubble in Beijing, and some on the streets. I borrowed some things from friends and family, and one of my classmates got his father to lend me several tons of cement powder, which, after a few days of exhibition, I bagged up and returned to the construction site. The tiles were roof tiles from old demolished homes. I arranged all of these elements together, and covered the furniture and old household implements with the cement powder. It was as if a cloud of cement and dust had suddenly fallen from the sky, burying our experiences, our emotions and our histories, turning them into spiritual ruins. Placing “ruins” and the city together formed a portrait of that era.

Then, in 1998, I used photography to document the demolition and reconstruction of the historical Ping’an Avenue. That was a road I passed every day on my commute, and so I witnessed its entire demolition and reconstruction. Ping’an means “peaceful,” but during all of this, it was anything but peaceful. It was like winding through the rubble of a battlefield. I arranged these black-and-white photos together to create a street, and placed it on cement powder. Cement powder is the raw material of this era.

At this time, you also made a series of works closely related to your experiences and those of your family. For instance, you used concrete to seal up clothing from various stages of your childhood. It was like two worlds coexisting, one being the changing world outside and the other being your internal, individual memories and changes in your family. What did you think about the connections between these two?

When our generation was young, the education we received placed great emphasis on collectivism, while saying nothing about personality or individual growth. The collectivism at the time was about repressing individual energies. Since childhood, everything collective was seen as glorious. It stifled individual expression. We had to show that we had no individuality, and that collective benefit was the most important thing. The opening up of ideas in the 1980s liberated people’s personalities, and the desire for individual expression grew stronger. Actually, there’s no collective that’s wholly without individuality. Every group comprises very different individuals, and as these individuals grow, there are many similarities. Behind the appearance of individuality, however, there’s actually a lot of commonality. The changes that took place as we grew up can be presented in the form of clothing, and so I combined two different building materials to make Dress Box . Clothing is a building material of life that has witnessed my individual growth, while concrete is the developmental building material of a city’s growth.

Humans are social animals. When you live in this rapidly changing country, the values instilled through your education as a young person are constantly being challenged. The individuality and personality that were suppressed as we grew up were often released through the recognition and expression of the self. This self-expression is inextricably linked to the memories of the era and the changes in society. The early Dress Box (1995), as well as the one I made in 1999, are a composite of individual and collective memory. The Doors (1995) connects individual life and public life through a “door.” The world is composed of different personalities, people walking many paths and reading many books. It wasn’t as crazy back then as it is today, but I saw this trend, and I was indignant at the destruction of this ancient capital. I grieved for this passing culture. I was worried about this increasingly unpredictable future. My own artistic changes have always followed changes in life. The great wave of demolition and construction got me thinking about what home is, and my frequent international travels drew my thinking into international topics.

This is something that’s very interesting about you: you have this powerful perception of the changes in the city, and at a very early point you touched on a form of relationship between individual life and the surrounding environment. You’re very interested in the ways in which changes in the natural environment and the urban environment can affect people’s lives. You went to Tibet, not to find something exotic, but to look at people’s perceptions of the changing reality. Your expression was of anxiety about environmental pollution, as well as about issues of culture and religion. You wanted to explore the process of people’s participation in nature. In these early works, such as Shoes with Butter and Living Water , it seems you’d already begun to explore certain themes that you’d later develop more fully. Washing the River is quite a landmark work.

I made Washing the River in 1995, and then a year later, I made Shoes with Butter and Living Water in Tibet. Environmental issues have always grown out of development. As “development is the only solid principle” itself becomes a solid principle, environmental issues are being overlooked, to the point of today’s horrible air quality and water safety. At the time, the pollution caused by development was relatively small, but it was already threatening people’s quality of life. Why do people want to develop so quickly? Now it can’t be stopped. What will be the end result?

This anxiety has kept me thinking about these problems. The environment is a big issue. As the environment deteriorates, it will no longer be able to provide mankind with the conditions for survival, so who are the results of this rapid development intended for? One important juncture was an event called “Guardians of the Water” organized by the American artist Betsy Damon. I took part in this exhibition alongside many other Chinese and foreign artists. It was held in Chengdu in its first year, and that’s when I made Washing the River. The next year, I went to Tibet and made Shoes with Butter and Living Water. Tibet was always a “pure land” in my mind, but when I got there, I discovered that they were also facing the issue of pollution, and so environmental issues came to seem all the more pressing.

Your works have always contained a form of criticism of reality. You strive to discover problems in reality and excavate them, but at the same time, you also express a sense of helplessness in the face of reality, and you address this helplessness with satire.

Right. Though we are helpless, we must use our powers to do something. When more people speak out, it has an effect. Right now, environmental awareness is many times greater than it was in the past, but today, the environment can’t be protected by what we conceive as environmental protection.

How did you choose this language at the time? For instance, on one hand, you use readymade materials, the materials most readily available in a particular place, such as the bricks and tiles left behind by demolition, or concrete. Then there’s yak butter, that simplest of local materials. At the same time you also bring in elements from your everyday life, such as shoes and clothes. These are all very symbolic materials.

When these everyday objects are being used in everyday life, their practical nature is magnified, but their spiritual nature is overlooked. When they’re brought into art as a form of language, their spiritual nature is magnified. For example, how do you wash a polluted river? We can use scientific methods to purify and wash the water, but that’s a manifestation of physicality and chemistry. When the water is removed from the river, frozen and brought to the riverbank, and then passersby can take part in cleaning this “solid river” using clean water, it conveys thinking on a spiritual level. The spiritual nature of the object has been magnified, so that the practical side no longer stands out. This somewhat poetic act is mixed with helplessness, satire, wariness, and futility, but it’s also a carrier for reflection and criticism.

As for yak butter, this material is a hybrid of materiality and spirituality in the lives of Tibetans. They eat yak butter and also burn it in candles and lamps as part of religious offerings. Yak butter can provide nourishment while also illuminating the spirit. When this spiritual material is placed in shoes, which can carry people to distant places, it’s like a form of transcendence, like a spiritual vessel that carries brutality and warmth through the beautiful scenery, stopping at this shore or that, solidifying on the ground, solidifying in the photograph. Then there are the bricks and tiles used in my works. They’ve been stripped away from the old houses. It’s painful, and yet they dance together with their replacement, cement. Meanwhile, cement has some very special properties. It has a strong sense of texture. When it dries, it looks so light, gentle and malleable, but it’s very heavy. When it encounters water, it solidifies into stone, cold and emotionless. Finally, clothing that has been worn is like “skin” that can speak. It speaks of its experiences, and carries the warmth and aesthetic tastes of people.

These various aspects came to form a foundation for your mature works. Among your later works, people are quite familiar with those in which you use clothing, cloth and other everyday objects. This appears in virtually all of your works as a very basic language.

Yes. That’s been the case for many years. My mother worked in a clothing factory, and when I was young, I enjoyed watching her make clothes. We were all very poor back then, and my mother would often buy the leftover scraps of cloth to patch together clothes for us. I learned how to stitch and alter clothes from her when I was a child. It was only at New Year that I’d get a real set of new clothes, and so in my memories, clothing has always been something very precious. I’d wear one piece of clothing for years.

Yes, it was like this for all of us.

My interest lies in people’s experiences. I can look at old photographs for hours. Shitao famously said that he “scoured the mountains for his sketches.” I’ve replaced “mountains” with “experiences”: I “scour experiences for my sketches.” I see clothing as a second skin. Once it’s been worn, it bears the traces of the wearer’s experiences and times. It has expression, language, and connections to the times and history. I began using clothing I’d worn as a creative material and element in 1995. I love collecting things like this, because when I see them, I think about the times and events that took place when I wore them. These clothes are like shadows of memory. For instance, in Dress Box , the suitcase is a vessel for storing memory. I sealed the worn clothing in concrete so that it can never be reopened. It’s like I sealed up a stretch of memories, and now that it’s sealed, I’ll never see it again. I also used a needle to sew up the edges of the clothing, and in the process, the memories seeped out like water through the holes made by the needle.

Concrete is so fine and cold, and it solidified my individual impressions of history and the times. This artwork showed me the passage of time, of experiences and of history. Though this is an individual story, the colors and styles of the clothing represent a certain era. This resonated with a lot of people. Clothing is like a soundless voice, conveying the taste and identity of the wearer. Later, I slowly began collecting other people’s clothing. For instance, in Portable City , the clothes were collected from cities in different countries and regions, and I’d use the clothes from one particular city to make a representation of that city. When I did Paris , you gave me a lot of clothes. This is also an exchange and retention of affection. Through all these years, I’ve always wondered why I’m so interested in used things. What is saved and what is discarded is always a reflection of how we value materials. When we reuse materials that come from people’s experiences, we come to a new recognition of the concept of the “readymade.” In this consumer era, it’s particularly important to reflect on the dilemmas brought by consumption, and as I reuse these “experienced materials,” it becomes a starting point for recapturing value.

Portable City: Madrid

, 2012

Portable City: Madrid

, 2012

Your activities in China during the 1990s attracted quite a bit of attention, and you began to take part in more international events. There weren’t so many opportunities to exhibit in China before 2000. Most of the time, the artists had to find their own way.

Right. A lot of exhibitions were in improvised spaces or in people’s homes. Some of them were even held outside. There were a few scattered art museum spaces holding exhibitions, but these were often arranged among friends, and those exhibitions would only last a few days. Contemporary art was still in an underground state.

Later on, you increasingly took part in artist residency programs, traveling to Australia or Germany, staying for one, two or even four months, and taking part in international events. Did these experiences lead to a great shift for you? How has this influenced your works?

It was around 1997 that I first started having opportunities to exhibit abroad. The first country I went to was Japan, and then I took part in the exhibition “Another Long March” in the Netherlands. Then there was “Cities on the Move,” the international exhibition you curated with Hans-Ulrich Obrist. That was a very early collaboration between us, and it was very important for me, so I want to thank you for giving me an international platform. Even now, I get excited when looking back on it, because that exhibition was revolutionary in many ways, from the curatorial approach to the ways in which the artists’ works interacted. The entire exhibition was an artistic creation.

My artworks The Doors and Changes were part of the exhibition, always moving with the cities on the move, never getting stuck in some set form. Then, I had a lot of opportunities to take part in artist’s residency programs: a month in America, three months in Australia, and the longest, a year in Germany. Then I took part in many international biennials and themed exhibitions, and began to travel a lot. These experiences were very important for me. They opened up my vision. It became a part of my life, and I began to see more and think more. When you’re in China, you learn about the progression of the world through magazines, books, and information brought in by people returning from abroad. It’s quite passive. The things you learn about have been filtered. After I went out, I still had a biased understanding, but my choices were greatly expanded. When you enter into another life, this life becomes the object of your expression.

Could you be more specific about what really changed?

It was a change in the way I saw things. In the closed-off education we received as children, we were taught to see the Western world as a corrupt, exploitative, rapacious world of imperialism. After China’s reform and opening, this once dark world became a bright paradise to which people aspired. But when you go into that real world, you discover that there is no East or West as you once conceived it. These different ideological regions comprise very different sets of individuals, and are quite different from each other. In today’s globalized world, the intellectuals in various regions are wary of the homogenization of ideas, and increasingly criticize and reflect on the shortcomings brought about by globalization. I’ve had the opportunity to see the essences of many different cultures gathered together in the British Museum and the Met , learning about the developmental threads of world culture through various dimensions. These are things you just can’t grasp in the books and studies on art history and cultural history. It’s the same with interactions with people.

Then there’s the exchange between artists from different regions. Has that influenced you?

Exchange is very important, but I don’t speak any foreign languages well. The exchange between artists is one between souls, an exchange carried out through hand gestures and drawings, even the creation of means of exchange, changing our methods of expression through exchange. The cultural differences lead to much misreading. When artists from different backgrounds live together, aside from their artistic exchange, different habits and customs also form a channel for mutual understanding. The artists who really interest me are those who aren’t held back by harsh conditions. The value of a work of art is the value of knowledge and ideas, rather than the value of its materials, just as the value Duchamp gave us is much more than the simple readymade. Artists from different places have very different means of expression.

At the time, I had little art-appreciation experience, and so my main impression was that there was a rich array of means of expression, and that artistic language was very open. In those days, I was in a pretty poor financial state, so I could only use materials I gathered from my surroundings. Landscape (1999) and Bathroom (1999) grew as part of my residency project in Germany. In Landscape , I sealed objects from everyday life in cement bricks. Bathroom was carried out according to the unique properties of the Künstlerhaus Schloss Balmoral. The exhibition site was originally a hotel and each room had a bathroom, each with a different design. That was what made this hotel special, and it stemmed from a culture of respect for personality in differences. These bathrooms, with the walls removed, were found in the corner of each room. But the elemental qualities of the hotel fitted with the travel theme I wanted to express. I sealed various cosmetics and toiletries in the washbasins with concrete: hairpins, soaps, combs, lipsticks, all frozen in that critical moment in time between the beginning and end of a journey.

Starting at this point, travels and airports became important themes in your work, as seen in International Airport: Terminal 1 (2006). Every time you go on a trip, you put the image of the city in a case and carry it with you.

Travel has given me much inspiration and brought me a host of different types of artworks. Before my international travel experiences, I’d only flown in a plane twice. Modern transportation tools have shortened physical distances, as well as cultural time. As travel has grown more frequent, the airport has become a part of everyday life, and the public space of the airport has become an extension of individual space. Every time I pick up my luggage, it feels like carrying my home. The suitcase is filled with the necessities of life on the road, but it’s also a spiritual carrier. It’s like carrying your homesickness. But the city has grown too fast and too large, and cities around Asia and China in particular are increasingly looking the same. If you don’t look at the words and signs, many of these places have no recognizable traits. I began my Portable Cities series in 2001. In this series, I collected clothing worn by people in the cities I visited, and used these clothes to make small buildings that were then sewn into suitcases. These are expressions of my personal impressions of these cities I’ve visited. They’re all in suitcases of the same style, and they get carried around to different countries and regions for exhibition. To date, I’ve made nearly forty of them. This is a change brought about by my international travels.

These Portable Cities are getting increasingly complex. The one I like the most, Beijing , is the first in this series, as well as the simplest and most abstract. Beijing is where I grew up, and those landmark buildings have dissolved into my profound emotion for and understanding of this city. Spirituality is gained by discarding external recognizable appearance, and so it is in my Beijing: others can’t recognize it. The suitcase is a concentrated home for life on the road, and it’s an object that’s inextricably intertwined with globalization. Globalization is making the world increasingly small and increasingly homogenous. Everyone has enjoyed the benefits of globalization, but we must also bear its shortcomings. It isn’t necessarily a good idea to steamroll difference with sameness. The richness of the world now faces an unprecedented challenge. In later installments of Portable Cities , I’ve juxtaposed sameness and difference. I place emphasis on difference, but no matter how I emphasize it, it’s always covered over by sameness. I’ve been creating these cities for over a decade, and it’s become a thread running through my life. The artworks are no longer so important. What matters is how it leads me to understand unfamiliar cities and come into contact with other people.

Of course, there are other works, such as International Airport: Terminal 1 and Transfer Station (2010), which are connected to airports and luggage. The airport is a place for transfers, a place where strangers gather together, but it’s not your final destination or your home. It’s just a place where you stop temporarily, and then everyone runs off again. But when we travel more, we get this illusion that the airport is like home, or like your own space.

Something I find very interesting is that for you, life on the road is always linked to home. For instance, you made a project called One Year Away from Home , right?

One Year Away from Home was a one-year residency project I did in Germany in 1999.

A lot of your projects are connected to home. Next, you took your apartment building, as well as the most familiar new landmark buildings around you—which have been popping up all over China—placed them in a suitcase and went on a trip. This clearly implies that no matter where you go, you always have to have your home, or some image of it, with you.

I think that home is a foundation. Chinese people place great importance on it. When the whole family is together, they’re at home wherever they go. When I’m traveling alone, I’ll take things that recall my family with me. When I see them, I feel like my family is by my side. I brought a lot of things from home for the One Year Away from Home project.

This brings us to an important issue. Today, in this era of globalization, travel has become a very ordinary way of life. Twenty years ago, if you could travel out of the country, it was a big deal. Now it’s very common.

When I went abroad in my early years, it was very eye-opening. After all, the nation had been closed off for decades. It was rare to get a chance to travel abroad in those days, and it was difficult to get visas, so if you had a chance to do so, everyone would be jealous. Then, gradually, everyone became busy, and all of the new opportunities turned travel into a part of everyday life. In today’s globalized era, everyone is in a state of flux, with material flows, spiritual flows, cultural flows and information flows making for rapid change in our world. The world really has got smaller. When something happens in one region, it can affect surrounding regions and even the entire world. Korea has started complaining about the smog from China.

There’s research showing that the weather on the U.S. west coast is being affected.

Yes. Everything is connected now. Meanwhile, people are growing increasingly infinitesimal, and in the end, we’ll be forced to flee our destroyed planet. But where can we go?

In these circumstances, what do you think is the artist’s unique role?

I think that artists have the power to act. They’re more sensitive to things, and are able to unearth ordinary things, things people may not place so much importance on or things they may not see, and to express those things in formal language, raising issues, and getting people to think.

Flying Machine

, 2008

Flying Machine

, 2008

In your works on travel, the concept of home is often expressed through soft materials, such as suitcases and clothes. Later, this concept seems to have increasingly become a concretized space, a living space, an architectural structure. In turn, this living space is often connected to the tools of travel. For instance, you’ve combined a plane and a car, turning them into a strange composite structure that’s at once a building, a means of conveyance and a home. Examples include Flying Machine , exhibited at the Shanghai Biennale, the constantly extending theme of the car, or these magnified human organs.

I shrink the buildings of a city down until they can be put into a suitcase and carried. With the human organs, I magnify them until you can step inside them. Large or small, they all engage in a non-ordinary exchange with people. I’m very interested in bringing people into spaces for direct, physical experiences. They’re all made by sewing collected clothes together. Introspective Cavity is an enlarged womb. It allows the viewer to return to where they started for introspection and reflection on all of the things we do. Thought is a giant brain that seems to have been dyed with blue ink. People can stand in this brain and ponder the “color of thought.” The image of a “big mind” or a “big heart” is often used to describe someone with a lot of ideals, with far-reaching goals or great ambitions. But when the heart is big, it implies that this organ requires treatment. The work, Motor , is an enlarged heart. It uses people’s external “second skin” to create the great motor within us. It’s an organ of radical progression, cessation, and suffocation.

This series ponders people’s inner landscape and sentiments, using architectural structures to bring people back to clothing that has been stitched together by varying experiences. Flying Machine is a means of conveyance but also a building and a public space, a place where people interact. Viewers can enter into this transition zone between the city, the countryside and the world. This flightless flying machine is a marriage of three different means of conveyance: a tractor, a sedan, and a plane. The central section where they link together is constructed from steel bars, which are covered with clothes collected from the outskirts of the city. These three means of conveyance bring together the countryside, the city and the world. Their use to produce a new flying machine brings together difference and consensus, fusion and contradiction into one whole. Placing different levels of life and different speeds of development on a single platform creates a hybrid conceptual space. This is also the reality of China, a confluence point between different eras. This flying machine is also about stopping to rethink and re-imagine speed.

This is perhaps a phenomenon of Chinese urban development, a new form for the city. The transformation between countryside and city has been too rapid, to the point where we’re unable to define what it actually is. Among these things, what’s been the most influential source of inspiration for you? What books or people have had the greatest influence on you?

Ultimately, society is what’s had the greatest influence on me. The drastic changes in society have made the world of my experience very rich and even a bit bizarre. Then there’s demolition. Demolition has been a part of my life for nearly thirty years. Now, the demolitions often take the form of forced eviction. The forced evictions in China have ended up demolishing quite a few lives. For the most part, this happens to people you don’t know, but when it starts happening to people you know, it can hit you very hard. But people need hope, and art has become a channel for hope.

In recent years, I’ve been making a series of installations entitled Temperature , in a kind of response to the various conflicts in the world. A world constructed brick by brick has been turned to rubble by various forces in the world. This rubble was once a part of a wall or a pillar. It has witnessed life and been a part of experience. When a wall or pillar is disintegrated into bits of rubble, this rubble in turn absorbs the energy that destroyed it. This includes contention between people, between humans and nature, between competing interests, between powers, between ideologies, and between concepts. The rubble becomes the remains of these various forms of contention, silently taking on a powerful sense of tragedy as it collects this tragic energy. Clothing, on the other hand, is like a soft building that attaches to the human body as a second skin. It has multiple properties and carries different identities, classes, tastes, cultivation and different cultural orientations. When clothing is ripped into tatters or threads, its different properties are disintegrated, presenting a kind of “equality” in “inequality.” Although it’s utterly fragmented, it still retains people’s character, even a spirit. The latent temperature it retains grows within the cracks of the rubble, providing an outlet for the cold, silent, even brutal energies of reality, radiating new warmth.

I’ve noticed that you have a photograph of a helicopter that crashed in Cambodia. This was the prototype for a large machine you made later, right?

Yes, it’s a military helicopter. This is a strong sensory onslaught. I came across it in 2001 on an inspirational trip between Thailand and Cambodia. I became intensely interested in it. It had been fenced off, as if they were afraid it would explode—there was that inherent danger. Because of language issues, I never found out if it had been shot down or had crashed for other reasons. As soon as I saw it, I felt that this was my artwork, so I took photos. Having crashed to the ground, this once fierce and deadly helicopter looked like a soft fabric sculpture. Its twisted skin and the exposed, complex parts formed a stark contrast. In this state of destruction, it took on a stark beauty. A massive machine had become fragile. All of this fit really well with my own perceptions.

In many of your later works, a new relationship emerged between wars, violence, weapons and everyday life: you turned mundane, simple things into weapons.

That was Weapon , which I presented at the exhibition you curated for the China Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

But you actually made this work before then, right?

In 2003.

How did you conceive of this transformation, this sudden shift from warm memories of home to a rather violent image?

Actually, the warmth is still there on the surface, wrapped around everyday objects, which appear to be spears and missiles. It’s a structure that uses traditional forms to imitate a TV tower, that symbol of today’s media authority. Sharp knives are attached to the tips of each spear. Everyone thinks all these pretty things are hanging there, but they don’t notice the inherent danger. Beneath that warmth lies violence and brutality. It’s like the relationship between cement and clothing. In our real lives, many brutal realities and violent threats are concealed beneath warmth and gentleness. There’s a great concealment. Thus, when this violence and brutality is revealed, it appears even more brutal and violent through the contrast. I really like this contrast. It doesn’t appear so powerful, but when you take a closer look, you find this lingering fear.

Later, in the Venice installation, you took everyday objects, particularly feminine ones, such as plastic washbasins, and turned them into weapons.

Washbasins, clothes-drying racks, pot lids, etc. They’re linked with clothing to become weapons. Together with the old rusty oil tanks in the exhibition space, the place turns into an armory. In Venice, I presented this powerful contrast between the giant oil tanks and that mass of “clothing weapons,” and beneath all of that, the deadly power of sharp knives had been concealed everywhere.

Then, in this period, certain unique events led you to change your interpretation of these objects. After 9/11, terrorism became an important theme.

Yes. In 2001, at the Siemens Technology Development Corporation office in Beijing, I used old clothes given to me by the employees to create a giant airplane, which I hung up in their office. The exhibition opened on 10 August. Who knew that a month later, 9/11 would happen, and a real plane would crash into an office building, leading to the loss of so many innocent lives? We then entered into the post-9/11 era, an era of contention and coexistence with terrorism.

Living in China, as an artist, what’s your view of this terrorist act that took place in America? At the time, China wasn’t under the direct threat of terrorism.

What we share is that we’re all people. The first thing I felt after 9/11 was shock. I couldn’t believe it. How could this happen? How could this happen in America? But it really did happen. Brutality aside, the fall of those two towers became the marker of a new era. We must take a new look at the relationship between weak and strong. We must rethink values, rethink the set rules, the differences and the existence of different cultures. This amounts to taking a new look at humanity, at society. The whole world underwent a rigorous security inspection.

The international airport checkpoint.

The mutual trust between people was challenged. Then, a new model of security check emerged, where people are now stripped naked in front of machines.

3D scanning.

Now human dignity is under fire, and a lot of money has been wasted.

The existence of this terrorism has led to the loss of trust between people. But terrorism is very complex. The struggles between competing human interests have led to a crisis of trust, in turn producing even more terrorism.

Yes. I even did a series called Fashion Terrorism (2004–05). The first work in the series used old clothes to make things you’re not allowed to take on the plane, such as guns, knives, aerosols, grenades, a lot of stuff. I took this stuff through airport security, and the security personnel would ask me to open my bags. When they touched these things, they saw that they were all soft. They laughed and brought the other personnel over to see it. The terror was dispelled. But it’s not so easy to dispel the crisis of trust in reality. Perhaps it will become even more intense.

Fashion Terrorism

, 2004

Fashion Terrorism

, 2004

Your works point out this change in relationships between people. You advocate coexistence and trust between people. You place great emphasis on this type of community life, this collective life. This is the remembrance of the street life in old Beijing, with old people singing opera, walking their birds, and drying clothes in the streets. At the 2002 Gwangju Biennale, you invited the audience to take part in the formation of a work based on this theme in order to share in this experience of collective life. In Prize of Desire (2003), on the other hand, you presented the absurdity of competition within the collective. It was quite satirical.

This collective, participatory aspect is one attribute of my artworks. Take for instance my early work Washing the River , or the later works Beijing Opera, Teahouse, and Prize of Desire : the audience is right there. I maintain this particular attribute in other works by allowing the audience to step inside. Drinking tea, eating food, and chatting are the most common forms of everyday recreation among the Chinese people, and are not limited by place or space. In Beijing Opera , the audience sit on stools as they listen to the stories of old people. In Teahouse , they can sip tea and munch on sunflower seeds, just like the laid-back residents of Chengdu.

The common greeting in China used to be “Have you eaten?”, but now it’s “Are you busy?” We can see that busyness has become more important than eating, as if we can only eat well once we’ve been busy. The constant desire for growth is leading everyone in this consumer society. Sometimes relaxation is important. It’s another kind of response to the busy world and a busy China: stop and take a break. Sometimes I enjoy raising serious issues in humorous ways. It’s more relaxed that way. The Prize of Desire series produces certain hurdles for the normal rules of sports games, making the process of the game more interesting than the result. This is also a reflection on the rush for personal gain these days. Here, the expectation of the prize and the process of seizing the “prize of desire” are undermined by the rules, which aim to make trouble.

We began to release the self and highlight individuality in the 1980s, but sometimes the endless expansion of self becomes selfishness. I’m interested in the relationship between the individual and the collective. Sometimes involvement in a collective allows us to rethink the place of the individual in this ever-changing outside world, as we see in the long minivan Collective Subconscious (2007). The individual is the unit of which the collective is made. That stretched-out minivan takes 400 individual experiences and compresses them to form a spiritual space for the collective subconscious. When you enter it, you can see the stained-glass windows of a church. In this process of collective integration the individual has been assimilated. This is the stumbling rush forward of the little horse pulling the giant cart. This once small minivan, having been forced to become something much larger, has become an unbearable energy.

You’re saying that you’re becoming increasingly interested in the sharing and spirituality of the collective?

Yes. I really like these relationships. They’re about how people figure in the collective.

You sometimes collaborate with other people, for instance with your husband, Song Dong. How do these collaborations influence you?

Dong and I have collaborated with choreographer Wen Hui and filmmaker Wu Wenguang on dance theatre, and that experience changed the way my works interact with the audience. There shouldn’t be boundaries in art. I’ve also collaborated with Dong, but we’re both independent artists, and this collaboration was difficult. To truly collaborate with someone, you may have to give up certain things. In 2001, we created the collaborative method known as the “way of chopsticks.” This is a collaborative method based on the nature of chopsticks. Once the two parties have agreed on the same rules, they then separate and make their respective parts in secret, independently completing their own components, which will eventually be put together in an indivisible artwork. The way of chopsticks is built upon a foundation of mutual trust, equality, and independence between the collaborators. Mutual trust is the essence of the way of chopsticks, while equality and independence are its soul. Once we had the “way of chopsticks,” we could maintain our independence without compromise, and we collaborated on many artworks. I hope that in the future the way of chopsticks will become a collaborative method for the world.

In recent years, your works have touched on certain very specific social incidents that have been widely covered in the mass media, such as the motorcycle artwork or the story of the baby left in the bathroom. That’s to say, you’ve shifted from rather sweeping themes to more concrete issues connected to certain stories. Is this related to the shifts in the means of interaction in Chinese society? Direct interaction between people is increasingly being replaced by the media. The media is becoming a medium for our exchange, perhaps even the only means of exchange. When we look at reality, we’re no longer directly viewing the things themselves, but seeing them through media reports. Our views of reality are created by the media.

This is the era of media. Much of our understanding of the world is gained from various media. It’s a filtered reality. I’m not re-creating these facts, but instead gaining inspiration from the information in the media and expressing my own understanding. For instance, with the artwork about the baby that you just mentioned, my inspiration came from a news report. I was shocked when I saw it—I just couldn’t understand it. That haunted me for a while, and then I decided to make this artwork.

Could you describe this incident?

I can’t remember where it was, but it wasn’t Beijing. Somewhere, under a bridge, they discovered a baby, just a few days old, tiny. It was wrapped up. It had a pair of scissors stuck in its chest. When they looked at the scissors, they were the kind used by workers in clothing factories, so they guessed that the baby’s mother must have worked there. Also, the baby was a boy. At the time, most abandoned babies were girls, or there was something wrong with the baby. But this particular baby was healthy. Luckily, a good person saved this baby. Why would such a thing happen? Most people could never be so cruel to their own child. It got me thinking that people’s loss of conscience has reached a crazy extreme.

I just couldn’t understand how human nature has become so distorted, how our society has got to this point. Then Dong and I were invited to hold an exhibition at REDCAT in Los Angeles in 2006, and we decided to use the way of chopsticks to create an artwork called Restroom . It was devised as two simultaneous solo exhibitions, with me making a women’s restroom and Song Dong making a men’s restroom. Dong turned the men’s restroom into a plastic golf green. I made a wax sculpture of this baby and placed it in my women’s bathroom. In China, many abandoned babies are left in restrooms. The public restrooms in the old Beijing neighborhood have fifteen-watt bulbs, so they have this gloomy yellow light. In my restroom, I used a giant crystal chandelier. The simple squat toilet was like a Minimalist sculpture. It looked a lot like our society, where the crude and luxurious stand side by side. I think that this juxtaposition highlighted people’s unconstrained desires, or those distorted desires and pursuits. It’s this very distortion that has led to the outcomes and social issues we don’t want to see. The motorcycle artwork, on the other hand, expands on the punchline of a joke. I heard the joke and laughed at it, and then I thought that there were profound ideas within it, so I made the artwork.

What was the joke about?

It’s a story about two show-offs. The joke is called “Wild 725.” Dong told it to me. A Wild 725 is a motorcycle. The joke goes like this: there was a small-time boss who’d been saving up for a long time. One day, he took a leap and bought a BMW. He took it out on the highway to show it off. He expressed his excitement and happiness through loud music, which wafted out of the windows. Just as he was reaching a state of ecstasy, he was interrupted by the thunder of an approaching motorcycle. He furrowed his brow and looked out of the window to see a motorcycle riding up to his car. The motorcycle rider shouted to him: “Hey, have you ever ridden a Wild 725?” With that, he passed the BMW so fast, it was like he’d stopped. This got the BMW owner mad. “Who dares race me on such a crappy ride?” As he was saying this, he was pressing the gas to the floor. It wasn’t long before he caught up with the motorcycle and passed it, and the driver felt great. But it wasn’t to last. The motorcyclist caught up with him again, and as the motorcycle passed, the BMW driver again heard: “Have you ever ridden a Wild 725?” But this time, the words were carried away by the wind, because the motorcycle was already ahead of him. Now, the BMW driver was getting really angry. He stomped on the gas and shot forward like a rocket. He quickly caught up with the motorcycle again, and now he was quite pleased with himself. But just as he was congratulating himself, the motorcycle shot out in front of him, and again he heard the words: “Have you ever ridden a Wild 725?” The motorcycle disappeared. Now the BMW driver was enraged. He drove as fast as he could in pursuit of the motorcycle. Before long, he saw a toll booth, but there wasn’t a gate there. Maybe the kid on the motorcycle had knocked it off. But there was no time to think about that. He sped forward, and as he passed the toll booth, he saw the kid and his motorcycle lying on the road. The BMW driver slammed on his brakes and pulled over next to the motorcycle. He saw that the motorcycle’s back wheel was still spinning. He was about to scold the kid, but then he saw him lying there, bleeding, and saying: “Have … you … ever … ridden … a … Wild … 725? Do … you … know ... where … the … brake … is?”

So my motorcycle work is called Where is the Brake? It’s saying that today’s society only cares about rapid development and can’t stop because it doesn’t know where the brake is. That was in 2005. Now society has already crashed.

As artists, do you need to apply the brake as well?

Yes. Everyone is very busy.

But at the same time, you must open up another space. For instance, in your recent works, something that looks like a satellite has emerged. What is it? A black hole?

Yes, Black Hole . It’s in the shape of a diamond.

But the concept of the black hole is connected to the universe.

Yes. I’ve read many books about heavenly bodies and the universe. The black hole is a theme that has interested me recently. I’ve created many different works on this theme, some of them mixed-media paintings, some of them mixed-media sculptures and some of them photo works. This work was created in New Plymouth, New Zealand. There’s a port there, and a lot of shipping containers. There are lots of goods coming and going from around the world every day. This Black Hole shipping container is based on the most basic twenty-foot container, an essential object in our global era, and made using the same materials. The dimensions of the work are determined by the standard dimensions of goods. The black hole is a heavenly body with immensely powerful gravity, so powerful that even light can’t escape it. The black hole can serve as a stand-in for an inescapable predicament. Human desire is like a black hole, devouring everything. The shipping container is a vessel of logistics. By the time they’re retired, they’ve truly been everywhere and seen everything. They’ve served as the clothes and carriers of desire. Their experiences are the experiences of desire and demand. The diamond is also a vessel of desire. This rare natural object is the carrier for so many unnatural things. I combined these two vessels of desire to create an empty, colorful shell. It forms a black hole through which we can rethink our relationship with nature and society.

Last year in Beijing, I made another diamond black hole, this one made from T-shirts. Each shirt contained text and pictures. They were the dreams and desires of the people who wore them. Some were brand names, some were fake brands. I brought these various reflections of value together onto the surface of that black hole, bringing in more layers of meaning. These diamond black holes have light inside—the kind of changing, multicolor lights you see in nightclubs.

Black Hole

, 2013

Black Hole

, 2013

If I asked you to look back over everything that you’ve done and select five representative artworks, which ones would you choose?

Five representative artworks … That’s a difficult decision. I’ve just made too many. I can’t choose. But there are expressions of different directions. I had my early beginnings, and then I developed them and went deeper. The early work Dress Box is probably quite important. That was the beginning of my use of used clothing as a material. Of course, then there’s concrete. Portable Cities is also quite important. It’s a microcosm of my international travels. Ruined City ponders changing cities, while Washing the River focuses on environmental issues and is a collective participatory artwork. Of course, the way of chopsticks used in my collaborations with Dong was also quite important. Actually, the works we’ve discussed today, such as Shoes with Butter, The Doors, Weapon, Collective Subconscious, Temperature, and Thought are all very important. Then there’s the autobiographical Yin Xiuzhen . I just can’t choose. Also, now that I have a child, I’m anxious about the future, so I think the giant wheel in Nowhere to Land is also very important.

How did this big wheel artwork come about? Why is it called Nowhere to Land ?

After I had my child, “the future” became very concrete. Anxiety and worry followed me at every turn. Our society is increasingly focused on profit, contradictions are intensifying, and our environment is deteriorating. When I made Where is the Brake? , I was already beginning to be aware of the severity of the problem. Now, it’s getting even worse. As mankind’s vision expands, we’re coming to realize how tiny our planet is. It seems that all living things are in a struggle for survival. Mankind thinks we’re the most powerful, and is taking all of the resources. Profit has become the core of everything. After all of the struggles, after we’ve lost our spiritual home, after we’ve lost our natural home, we’ll have nowhere to land with our “greatness.” Mankind’s unbridled avarice will eventually lead us to devour ourselves, to devour everything, becoming a black hole. I don’t think I’ve ever felt so clearly just how alone we are in this vast universe as I do today. I’m deeply worried about my child’s future. I’ve installed a giant wheel on the earth, but still it has nowhere to land. This was the theme of my solo exhibition at Pace Beijing last year. One installation, Life Raft , was made of several couches. That was a space for thinking about the future in a time of crisis. But I installed a series of exhaust pipes from different cars in a ring around it. We don’t know where this “life raft” will take us. If we start it up, we won’t know which direction it will go. This isn’t just a problem for China, but for the whole world.

Do you think we’re at a point of no escape?

Yes, or at a point where we need to find an escape. Maybe we won’t be able to find it.

Will that be the next phase of your work, unfolding around this theme?

Perhaps. I made those Fireworks paintings. It’s not just about sparks and fire. It plays on the Chinese word for fireworks, which means “smoke flowers.” Each painting is of a firework about to be extinguished. It’s that lingering shine that comes after the splendor and before the destruction. But this is a result of the painting material: plastic acrylic on wood frames. They’re hung on the wall. As I was painting these, I was in a horrible mood. I felt like I was about to die, like a firework on its last legs.

Have you returned to painting?

I won’t rule out painting, but this is different from the painting I did before. I’m making painting sculptures or painting installations. It was the smoggy weather that got me thinking about new energies in painting. The styles and forms of Chinese landscape painting have benefitted from the unique scenery and aesthetic ideas of China. That realm in the cloudy mountains, somewhere between existence and nothingness, gave me the conceptual imagery. Today’s smog isn’t just a visual obstruction, but a killer as well. It’s the mark of unrestrained development. How to express this spectacle and pain of our era? The growth of this smog comes at the cost of the health of several generations. Spiritual smog is even scarier. I used wood frames to make the kinds of barriers you see on the roads, and then stretched canvas across them, painting scenes from the streets of Beijing, such as the Central Axis, political sites like Chang’an Avenue and Tiananmen Gate, markers of development such as a missile pad and an aircraft carrier, and then covered up these images with a bright, glowing paint. These dazzling colors are a haze over everything, giving the sense of drifting. From head on, they look like concrete barriers, but from behind, they’re just empty shells.

The haze has turned the world’s pollution into a new aesthetic definition.

When foreign friends come to Beijing, some of them say it’s beautiful, with the beauty of a Chinese landscape painting, but they see this “beauty” as poisonous. It’s not like the beauty of the past. The fog historically seen on Mount Huang was poetic, the stuff of dreams. Today’s smog is a “poisonous beauty” that isolates man from the world.

[Translated from Chinese by Jeff Crosby]