We tend to think of Edgar Degas as a late-19th-century artist, which he mainly was (he died in 1917), and maybe even more of an early-19th-century artist, a draftsman in the tradition of his hero Ingres. But on the later end of his career, in two feverish bursts of printmaking, he sped up to and then surpassed his own time. In the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition “Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty,” which opens on Saturday, he looks very much like a 20th-century artist—one who mixes mediums freely, welcomes abstraction with open arms, takes in the highs and lows of urban culture, and embraces all the latest technologies.

His contemporaries, of course, couldn’t make those connections the way we can from our 21st-century vantage point—but they could tell that Degas was on the verge of something. As the writer Arsène Alexandre observed, the artist was “most free, most alive, and most reckless” in his monotypes. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé picked up on a “strange new beauty” in these often muddy-looking works. And the artist Camille Pissarro, who was on the opposite end of the political spectrum from Degas, approvingly called him an “anarchist…. [i]n art, of course, and without knowing it.”

Below are some key works and ideas from the exhibition, which runs through July 24.

1. HE WAS MAKING PROCESS ART AVANT-LA-LETTRE

Degas called his monotypes “drawings made with greasy ink and put through a press,” and relished the various stages of making them. He took full advantage of the fact that monotypes (unlike other kinds of prints) can be manipulated right up to the moment they are printed, working and re-working the ink on the metal plate with his fingertips and palms and a number of implements including sponges, rags, and brush handles. Even after printing, Degas often went back to the plate to make further adjustments. The poet Paul Valéry compared him to “a writer striving to attain the utmost precision of form, drafting and redrafting, canceling, advancing by endless recapitulation, never admitting that his work has reached its final stage.”

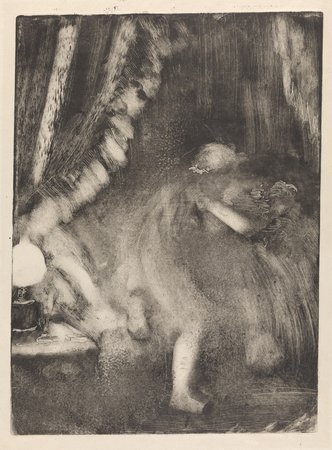

Bedtime (Le Coucher), c. 1880-85. Monotype on paper. Plate: 14 7/8 × 10 7/8″ (37.8 × 27.7 cm). Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design / The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design.

Bedtime (Le Coucher), c. 1880-85. Monotype on paper. Plate: 14 7/8 × 10 7/8″ (37.8 × 27.7 cm). Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design / The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design.

2. HE EMBRACED REPETITION AND SERIALITY

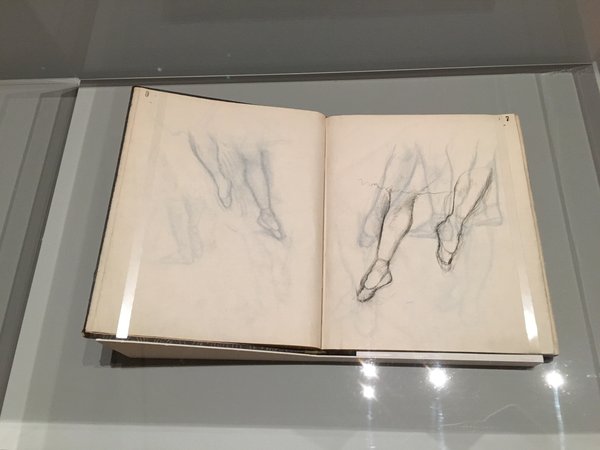

And he was doing itbefore the Cubists and the Minimalists. “It is essential to do the same subject over again, ten times, a hundred times,” Degas told his friend the artist Paul Albert Bartholomé. The intent focus on dancers, horses, and bathers in his paintings and pastels is one expression of this credo. Another is his tendency, in his late work, to flip and repeat specific figures within a single scene, as in the painting Frieze of Dancers (below), a tactic that seems to come directly out of the inversions and multiplications of printmaking. Elsewhere in MoMA’s show are counterproofs of charcoal drawings (made by running them through a printing press to produce a reversed image) and a revelatory album of drawings on translucent paper, which he worked through in reverse (making a drawing and then using the previous page to trace it or rework it.)

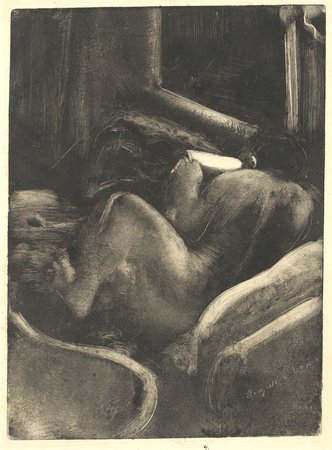

3. HE FOUND NEW WAYS TO SHOW THE FEMALE BODY

Whatever you make of his attitude towards women, which the writer J.K. Huysmans characterized as “an attentive hatred, a patient cruelty,” Degas innovated new approaches to the female physique in his monotypes. His strained and contorted nudes, scrubbing their feet in washtubs or even fussing with chamber pots, are naked but defiantly non-seductive. They could never be mistaken for the Venuses and Odalisques of academic painting, the stuff of Degas’s formative years (when he adored Ingres and studied with one of the master’s protégés.). Nor are they pornographic, even when the nudes in question are sex workers, as in Degas’s infamous series of monotypes set in brothels (works that mainly show the prostitutes lounging and chatting as they await customers). As one critic of the day put it, Degas was exploring “a host of positions that had interested no painter before.”

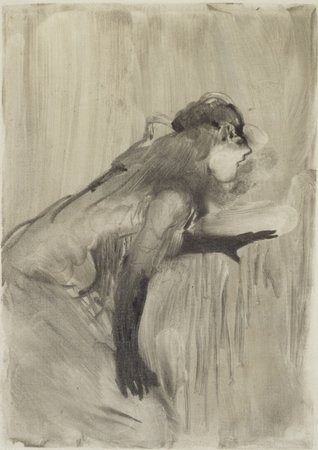

4. HE MADE ART THAT CELEBRATED PRIVACY

Even as it gave the illusion of voyeurism. The bathers in his works are anonymous, and although their backsides may be exposed, their expressions and interior lives remain off-limits to us. He also made images of women getting ready for bed that seem to have an element of personal ritual, as in the above monotype of a woman reading. Some of his urban scenes also preserve anonymity, as in a study of two passers-by that captures their attire but blurs their faces. As MoMA’s curators put it in their exhibition text, Degas “accessed and expressed privacy in a visceral way.”

Top: Woman Reading (Liseuse), c. 1880–85. Monotype on paper. Plate: 14 15/16 x 10 7/8 in. (38 x 27.7 cm), sheet: 17 7/16 x 12 13/16 in. (44.3 x 32.5 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Rosenwald Collection, 1950.Bottom: Heads of a Man and a Woman (Homme et femme, en buste), c. 1877–80. Monotype on paper. Plate: 2 13/16 x 3 3/16 in. (7.2 x 8.1 cm). British Museum, London. Bequeathed by Campbell Dodgson.

Top: Woman Reading (Liseuse), c. 1880–85. Monotype on paper. Plate: 14 15/16 x 10 7/8 in. (38 x 27.7 cm), sheet: 17 7/16 x 12 13/16 in. (44.3 x 32.5 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Rosenwald Collection, 1950.Bottom: Heads of a Man and a Woman (Homme et femme, en buste), c. 1877–80. Monotype on paper. Plate: 2 13/16 x 3 3/16 in. (7.2 x 8.1 cm). British Museum, London. Bequeathed by Campbell Dodgson.

5. HIS LATE EXPERIMENTAL LANDSCAPES DIVE INTO ABSTRACTION

Around 1890, after a trip through the Burgundy region, Degas embarked on a deeply uncharacteristic series of landscape prints. He used the monotype process but substituted colored oil paint for the usual black printer’s ink; when accidents ensued, he embraced them, as in the green blob of Forest in the Mountains. Even when he refined the images with pastels, they retained a dreamy, imprecise quality and were admired by the Symbolists. Degas himself saw them as a kind of cinema; he said that the idea of the landscapes came from looking out from the door of a moving train.

Forest in the Mountains (Forêt dans la montagne), c. 1890. Monotype in oil on paper. Plate: 11 13/16 x 15 3/4″ (30 x 40 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest.

Forest in the Mountains (Forêt dans la montagne), c. 1890. Monotype in oil on paper. Plate: 11 13/16 x 15 3/4″ (30 x 40 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest.

6. HE INVENTED A HYBRID SUPER-MEDIUM

In monotypes, Degas found a radical amalgam of painting, drawing, photography, and film. Degas took up photography late in his career, as he had printmaking, and seemed to see both mediums as part of a larger study of light and movement. He found ways to combine them physically as well as philosophically, in some cases making monotypes on the photographic material of celluloid instead of the typical copper plate. (The transparent celluloid allowed him to flip the sheet over and see how the image would look in reverse, in a kind of preview of the finished print.) He also took shadowy pictures that are of a piece with the high-contrast “dark-field” monotypes he made by starting with a fully blackened plate and wiping away the ink. One of those photographs, at MoMA, shows Degas’s artist friend Pierre-Auguste Renoir and the poet Stephane Mallarme seated before a mirror; Degas and his camera are visible in reflection.

7. HE DRAGGED THE DAPPER FLANEUR INTO THE 20TH CENTURY

Among the monotypes at MoMA are many scenes drawn from the café-concert (dinner cabaret), the ballet, and the street, those haunts of the roving observer of modern life identified by Baudelaire as the flaneur. What’s most striking about these images is not the subject matter, but rather the way Degas accentuates sound, movement, and artificial light (as in the above image of a café singer illuminated by harsh footlights). He also uses oddly cropped compositions that play up the brisk, transactional tenor of life in the modern city. Catalog essayist Richard Kendall has an even more contemporary reading of Degas: “A comparison with the clamorous arrival of Pop art in the 1950s and ‘60s is not altogether fanciful,” as he writes in the show’s catalog, pointing to Degas’s “brash new colors and fragmentary compositions” and his “subjects chosen from the coarser side of city life.”

Café-Concert Singer (Chanteuse de café-concert), c. 1877. Monotype on paper mounted on board. Plate: 7 5/16 x 5 1/16 in. (18.5 x 12.8 cm), sheet: 9 1/4 x 7 1/16 in. (23.5 x 18 cm). Private collection.

Café-Concert Singer (Chanteuse de café-concert), c. 1877. Monotype on paper mounted on board. Plate: 7 5/16 x 5 1/16 in. (18.5 x 12.8 cm), sheet: 9 1/4 x 7 1/16 in. (23.5 x 18 cm). Private collection.