In charting the course of art history, the Museum of Modern Art is about as agile as an ocean liner: it takes three to four years usually to plan a show, and curators are careful not to steer its titanic collection off course with any purchases that are less than first class. (Just read this interview to get a sense of the methodical deliberation of those at the helm.) So when the grand Modern put together a show in less than a year, heads in the art world spin. The unusually quickened pace that was involved in mounting Jasper Johns’s “Regrets,” the surprise new show by arguably the greatest living American artist, seemed to attest to the tremendous confidence—and excitement—of the curators behind it.

The story goes that Ann Temkin, MoMA's top painting and sculpture curator, and Christophe Cherix, the head of the prints department, paid separate visits last winter to Johns’s Blue Barn estate in Sharon, Connecticut, where they encountered a fresh body of work hanging in the light-flooded studio. The 83-year-old artist made the two paintings, 10 drawings, and two prints over 18 months, editioning the prints just this January. The curators decided to whisk the works in their entirety into the museum, immediately. The show opened mid-March.

To find out what makes Johns’s “Regrets” so extraordinary, Artspace prevailed upon curatorial assistant Ingrid Langston, who helped organize the exhibition, to lead us through the exhibit and help decipher the work of the famously enigmatic artist. The exhibition is self-contained, almost hermetic, and as Langston explains, “a concentrated version of his working process as a whole.” Here’s the story of the elegiac body of work that begins with an old tattered photograph.

THE INSPIRATION

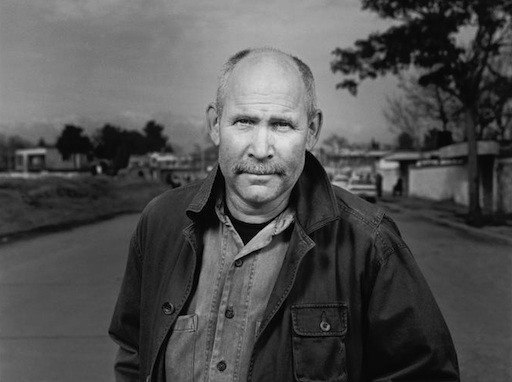

Two summers ago, the artist famous for carrying the legacy of Duchamp into the realm of painting—depicting flags, targets, numbers, letters, “things the mind already knows,” as he said—happened upon an old Christie’s auction catalogue containing a 1964 photograph owned by Francis Bacon. Commissioned as a source for one of his paintings, it shows Bacon's friend and fellow artist Lucian Freud sitting twisted and cross-legged on a simple quilted, iron-railed bed, his hand running through his thick hair, hiding his face. The print, discovered after Bacon’s death in 1992, had been treated to the artist’s particular brand of squalor: a large chunk of its corner is missing, it's splattered with paint, and is otherwise dented and creased by studio life. It quickly became an object of fascination for Johns.

“We have [the original photograph] here against a background because this missing black form in the lower-left corner becomes an essential component of Johns’s own compositions,” Langston explains at the entrance of the gallery. If “Regrets” were a musical composition, it would be a fugue, built on one short melody cycling through in different pitches and voices. This ragged photograph is Johns’s theme. What follows are its strange and gorgeous cycles.

FROM PHOTOGRAPH TO DRAWING © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

© Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

The curators believe Johns traced almost directly out of the auction catalogue for his first color pencil study on the right. “But as you can see,” Langston says, “when he traces it, the creases, splatters of paint, and the missing sections are treated with as much care as the image of Freud on the bed.” The photograph as a damaged object is faithfully reworked into interlocking blocks of color.

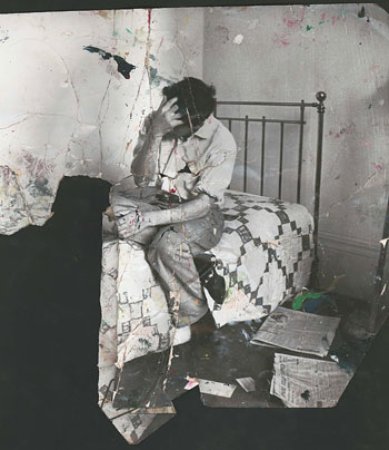

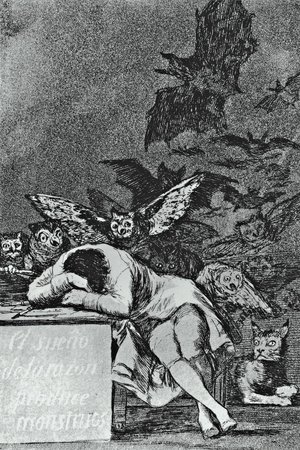

Meanwhile, Johns made another small pencil sketch of the photograph, this one muted and sparse, annotated with the words, “Goya? Bats? Dreams?” across its bottom. Here, the object “the mind already knows,” Langston points out, is an iconic work from the history of art: the dreaming man in Goya’s famous etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, whose slouched repose, crossed legs, and hidden face rhyme with Freud’s own contorted posture.

CHANCING ACROSS A PHRASE

Johns makes a similar associative leap when he adds a stamp to the upper-right-hand corner of the initial paint-by-numbers work: “Regrets, Jasper Johns,” signed with his looping fat-bottomed "J"s. Johns had ordered the stamp long ago as an efficient—and archly humorous—way to decline the innumerable invitations and signature requests that reach his studio. He had never used this office tool in his work before, and claims, that it just happened to be near the copy machine, and seemed a fitting description of Freud’s state of anguish.

With such an evocative phrase rubberstamped on the work, it’s too easy to reduce the series into a psychobiography of Johns. But that’s not the intent of the artist who upholds the Duchampian privilege of the viewer completing the work of art. (“Regrets belong to everybody, don’t they?” the artist told the Financial Times.)

The eureka moment comes when Johns returns to the patched color work to double and reverse the image. “Mirroring has been an important strategy for him in the past, perhaps linked to his intense interest in printmaking,” Langston says. Johns has now outlined the composition that will be recycled throughout the rest of the body.

A MEMENTO MORI EMERGES © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

© Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

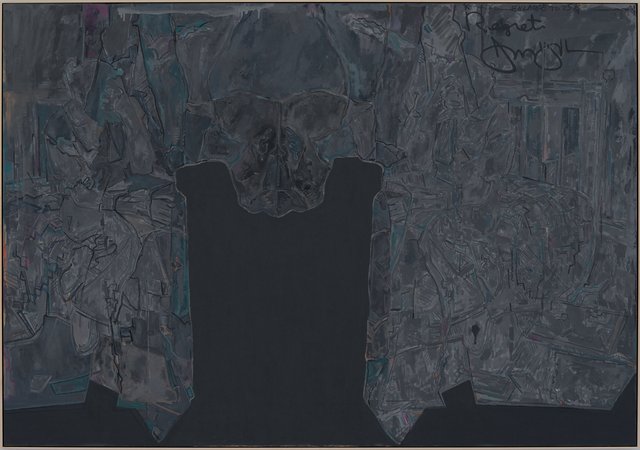

“For most artists, the monumental piece would be the culmination of a series but for him it’s the first place he goes,” Langston explains moving onto one of the two paintings, a key piece in the exhibition. She explains that Johns scales up the original mirrored study, including the stamp that appears on the right-hand-corner, leaving the printer-enlargement instructions in the opposite corner.

With the left-side now slightly cropped and washed over with grey, the spaces left by the gashes in the original photograph together transform into a central character. It's spooky—the absence of the photograph comes to form a presence in the painting. And, above, a looming skull emerges in the middle of the composition. Langston reports, however, that some visitors see other images in the middle form: a dog with sunglasses, an exoskeleton of a beetle, and a tombstone. When Langston herself first saw the jpegs, she remembers thinking it was the end of the bed fame—a rather cubist interpretation.

Is it a Rorschach test? “Well, if you want to go there, Lucian Freud is Freud’s grandson,” Langston replies with a laugh. But of course, Johns would dismiss such explicit readings, she adds.

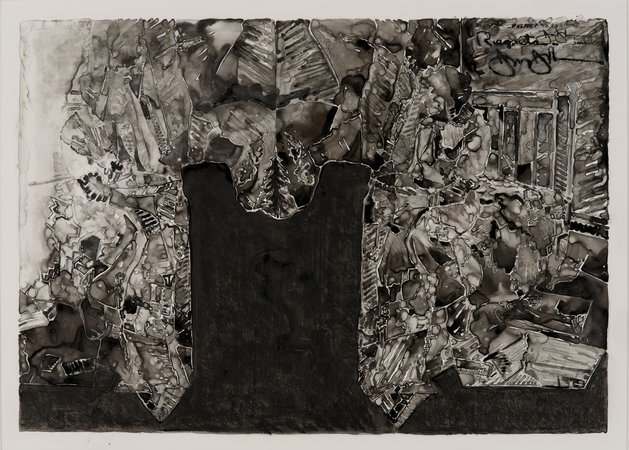

PUSHING TO ABSTRACTION © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

© Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

Simultaneously, Johns worked across medium, and in this above work, pushes the imagery to almost total abstraction. The most distinctly un-Johns-like composition, the watercolor figure is almost lost entirely underneath the layer of charcoal and pastel executed on thick, ridged paper. Over this same time period, the artist also made a series of states, and on display nearby are two printing plates. “You have to appreciate that he is plotting out the mirroring’s of the plates, which are mirrors themselves,” Langston says.

DILUTING THE IMAGE © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

© Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

In the 1960s, Johns discovered some sheets of plastic in an arts supply store in South Carolina, where he lived before New York, and started to draw on them with diluted ink. Johns returns to the makeshift medium with his new work, seen above in the agate-like effect. “The ink process is the perfect marriage of chance and control, which is the driving force in his work,” Langston says of the ink that pools and dries unpredictably on the nonabsorbent surface. In this stunning series of ink on plastic, the light appears to passing across the room, as if daylight were waning.

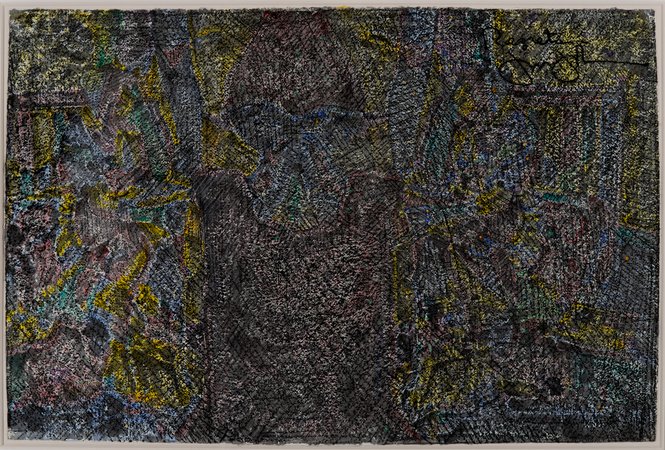

MAPS AND MOTLEY © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

© Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph: Jerry Thompson

“He’s looking at problems that arise in one work, finding solutions, bringing that to ensuing works, and then going back,” Langston summarizes. This late oil painting was originally rendered in bright orange, blue, and green tones, according to the curators who have photos of it in earlier stages in the studio. But John has gone back to obscure its luminosity, much like in an earlier watercolor, pastel, and charcoal work. The figure also harkens back to previous work, but from a different series—his famous maps. Indeed, the agonized sitter looks like the states along the eastern United States, and the central lower shape appears especially tombstone-like rendered in a textured cross-hatch. The color scheme also evokes the colorful attire of a count jester.

And now too a small panel appears on the iron bed railing. Is it a floating window? A painting inside a painting? Or perhaps, it is an escape, a hatch for the figure to exit through, out of the remorseful atmosphere.