The art world has long been familiar with the work of the Chicago-based artist Nick Cave due to the unforgettable, visually impactful quality of his so-called "soundsuits." Now, after the exceptionally successful run of his Heard NY performance in Grand Central Terminal' s Vanderbilt Hall—one of the city's most bustling thoroughfares—the rest of the city is familiar with him too. In fact, the piece, which was co-sponsored by Creative Time and the MTA 's Arts for Transit and ran twice daily for just one week (ending March 31st), could be compared to Christo and Jeanne-Claude 's legendary The Gates in miniature, so rapturous was the public response. Here, however, the art was not pure visual spectacle—it was a deftly layered commentary on ceremony (particularly costumed West African ritual), identity, and the place of dreams in civic life.

Consisting of 30 horses, each made of brightly-colored synthetic raffia (a kind of African palm) and containing two dancers from the Alvin Ailey dance company, the half-hour performance began with the performers unhurriedly putting on their costumes, one assuming the hindquarters, the other wearing a mesh-and-wire frame featuring the head. Then, as a soothing harp trickled out music, the "horses" moseyed around the cavernously vaulted hall, sashaying like show ponies (or models on a runway) and occasionally poking their heads out towards the audience members, as if requesting a sugar cube.

Partway though, however, the harp gave way to a drumming rhythm that gradually intensified until, in a moment of ecstatic release, the paired dancers uncoupled, the horse-headed halfs standing upright and strutting like totems while the posterior morphed into a tribe of frenzied Cousin Its, shaking furiously like pom-poms of vibrant ribbons. At the end, however, the soothing harp returned, the horses rejoined and resumed their placid walk, and a loudspeaker played the commuter's familiar line: "Mind the gap when getting on and off the train."

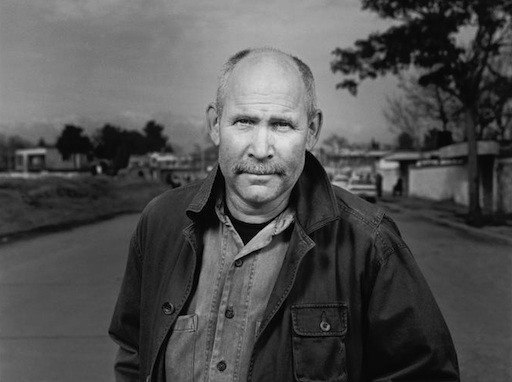

To find out about the ideas behind the performance, a version of which was debuted at the University of Northern Texas last year, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Cave about the origin of his soundsuits, what it was like working in Grand Central Terminal, and the advice he gives to aspiring artists and designers.

Your piece was an absolutely joyous event. During the performance I attended, everyone—including some of the art world's most hardened veterans—was obviously enthralled, smiling big smiles throughout, which is not a reaction people typically have to contemporary art. It seems to take you to another, dreamlike place. Did you know this was going to be such a crowd-pleaser?

When I was asked by Creative Time and Art for Transit to do this piece, my thought was, as an artist working within the public realm, what does it mean to be doing a piece that's for the public? I started to think about my role as an artist, and my civic responsibility as an artist. So I wanted to create a piece that really spoke about and brought us back to the place where we dream, that imaginary place in our minds that helps us stay connected to our own aspirations. We need to continue using that as a tool to mobilize us as we move through the world. Because we're so consumed by trying to hold on to our jobs and the state of affairs right now, that we're not dreaming anymore. So I wanted create that kind of experience for everybody.

Your work is always richly layered with the histories of art, fashion, and dance—yet instead of being weighted down by these references, it wears them very lightly. How do you manage to fit in so much context into your art while still allowing it to be buoyant and exuberant?

I think that just comes from my taking the time to understand what I want to do, and how to make it up. I'm multi-dimensional—I'm interested in all of these variables and in understanding their place within the context of the work. It's a lot of juggling, but for me it's really about bringing all of that together and finding harmony and balance.

What was the starting point for a work like this? Is the performance the primary thing you work towards? Or do you come from the soundsuits?

The starting point was looking at ceremonial rituals from around the world and the roles in which they play in terms of accessing the power within myth and this transformative state of mind. That's the beginning, and then you look at how you can bring in ideas around this central conviction, allowing that to be the truth within the work.

The performers in Heard NY are wearing variants of your signature soundsuits, which you have used in sculptures, performances, and other works over the years. For the uninitiated, could you explain what a soundsuit is, and where the idea came from?

The form is really a hybrid, bringing together a number of ideas. The impetus for the work came out of the Rodney King incident in 1992—how people would talk about the way King had worked out with prison weights, building himself into something larger-than-life scary, and how it took 10 men to bring him down. The idea of the soundsuit was an envisioning of what that kind of character would look like. Then I started to think about what it feels like to be discarded and dismissed—about the implications of that, and the materials that provoked that. So the first soundsuit was constructed entirely out of twigs. I was making a sculpture first—I didn't even think I could physically put this on—but once it was developed I physically put it on and moved around in it, and it made sound. And when I made that sound, it moved me into a role of protest. In order to be heard you have to speak louder. So that was something that was of interest to me, and it kept unfolding and really becoming much more versatile in that sense, and it made me think more, again, about my role and civic responsibility as an artist. It brought me to this level of consciousness that is very prevalent in my work today.

The soundsuits in this performance were clearly different from your earliest examples. For one thing, they are built in two parts to accommodate a pair of dancers. For another thing, they're much more mobile. And—most obviously—they're horses, not people. Why did you choose to use these for the piece?

Here they're very literal. I was looking at the history of early puppetry and adopted that as the imaginary palette that I'm investigating, and then came up with the horse as the image of choice. I also thought about that in relationship to Grand Central—looking at the flow of motion, the dance that happens right in the station, and the crossings that happen. I wanted to reflect on that as a point of reference for a kind of call-and-response. Then, I looked at Vanderbilt Hall, where the performance is taking place, as another sort of stable—a place where the crowd is penned as it waits to reach its destination.

What drew you to horses in particular?

Their majestic grandness. There is an implication of power and strength and dignity within the work that I think is very relevant. Yet it's all created out of synthetic raffia, so there is this other whimsical, visceral sensibility that keeps it in this playful arena that then allows us to go back to that imaginary space.

Considering how your soundsuits originally arose from a merging of social practice and performance, how does Heard NY continue in that vein?

We can look at the whole transformative element of the work. The opening of the performance, which happens right in view of everyone, mirrors our day-to-day morning ritual of getting dressed and following a dress code. There is this sort of masquerade component, but there is also this hiding of race, gender, and class. Each horse has a different design and a different mask on its face. What you're really looking at are these variables in terms of identity, in terms of this global world we exist in, and how we're moving as this global unit. I'm making reference to diversity and our differences, yet there is this sense of harmony, too.

The dancers in this performance come from the famous Alvin Ailey company, which you were long a member of for many years, and they're fantastic. What is it like working with such a large troupe of performers in such an overwhelmingly public space?

Well, we created the piece right on site, here in Vanderbilt Hall—maybe we had five hours of rehearsal time to sort of design it. And now, every day I'm here, I sort of look at the space as just a big sketchpad for me. It allows me to have a reading, and to understand how a work like this functions and what its role is in a larger scope. It brings me to a place where I understand what my purpose is, what my message is, how I want to be useful in the world as an artist, and what my capabilities are. This is an extraordinary platform for me to toss ideas around and to rely on the audience to provide me with the feedback in a call-and-response way.

It seems like you have received an incredible amount of feedback. What did you draw from the response?

During the private evening showing, which you mentioned, it was only adults, and they were just enlightened by that moment of reflection, the changing that rhythm, that heartbeat within our souls. Here during the day there's a group at the 11 a.m., and then they're pushed out to make way for a different group at 2 p.m.—so the audience continues to shift, which has been fantastic. But the audience really becomes part of this participatory experience, applauding the dancers as they come in and then again throughout the performance. It's really a wonderful experience to realize that not only are we providing a performance, but the audience is also providing the support that we need to continue to do this kind of work. And the kids are beside themselves.

In addition to being an acclaimed artist you also teach fashion at the Art Institute of Chicago. What are some of the lessons you try to impart to your students?

As a professor, I feel that the most important thing is to make sure that students get a full-circle experience, and that they leave school knowing how to trust themselves. They've got to have the passion and conviction to manage their careers. Being an artist is not by any means as glamorous as one may think it is. It's a lot of work, it's a lot of commitment and sacrifice. But if this is what drives you, there's absolutely nothing that can interfere with that pathway. I try to get them closer to understanding that.

WATCH FOOTAGE FROM THE PERFORMANCE (Video by Derek Schultz)