For young gallerists looking to open their first space, factors like a location in a major art city and preexisting relationships with collectors are often seen as the keys to achieving early and sustained success. For Hilary Schaffner and Ryan Wallace, the co-founders of Halsey McKay gallery in East Hampton, New York, these things didn’t seem quite so crucial.

Rather than try to compete in Chelsea or the Lower East Side, the longtime friends and artists drew on their roots in the Hamptons (Schaffner is a member of the Halsey family, among the first Europeans to settle the area in the 1600s; the gallery takes its name from the two gallerists' maternal grandmothers' maiden names) as well as their network of fellow artists to build their program, trusting that collector and critical attention would follow. Six years, two spaces, and dozens of shows later, it appears that they were right.

It helps that the Hamptons have long served as both a retreat and a rustic waterfront muse for artists as diverse as the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase and the Abstract ExpressionistsJackson PollockandWillem de Kooning, a fact that has drawn collectors from the city “out East” in ever-increasing numbers. Of course, Halsey McKay's roster of exciting emerging artists—like Lauren Luloff, Joseph Hart, andArielle Falk—doesn’t hurt either, nor does their semi-masochistic insistence on running two three-week shows at once all summer long.

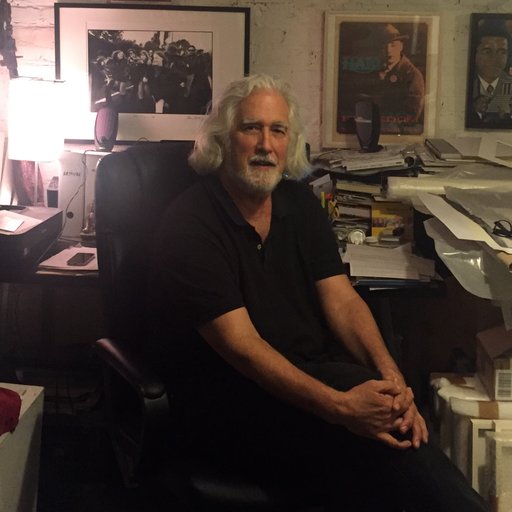

For the latest edition of our NADA Networkseries, Artspace’s Dylan Kerr caught up with the young gallerists to discuss their grueling exhibition schedule, their appreciation for art indie fairs, and why being 100-some-odd miles from New York City can actually be an advantage.

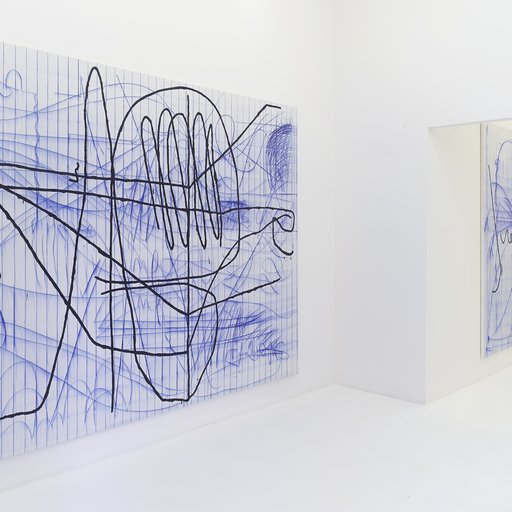

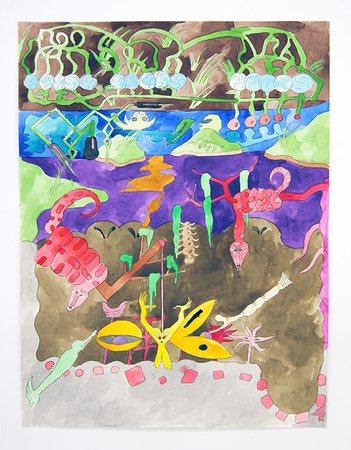

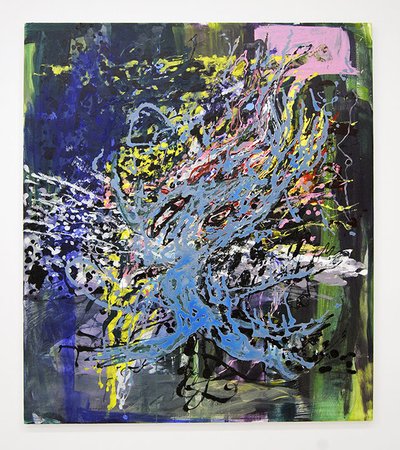

Note: All images are courtesy of Halsey McKay and show works from their concurrent shows of works by Timothy Bergstrom and Keegan McHargue, both on view through July 18th.

While the most of the art world prepares takes a break for the summer, you two have to gear up for your busiest season. What’s the advantage of having a gallery on Long Island versus a more typical spot in New York or L.A.?

Hilary Schaffner: A big part of the reason we opened the space out here, besides this great continuation of the artistic history that’s existed out here and our personal ties to the area, is that there weren’t a lot of galleries in this location showing emerging artists. It was a real opportunity to stand out and have our program recognized by a population that can support what we do.

When you say the population supports what you do, who are you referring to?

HS: A lot of our collectors are based in New York, so there’s a collector base that also comes out here to spend the summers. We can get our artists in front of them, and they can in turn support our programming. It’s also really nice to be able to feel like we’re making a contribution to the community. There’s been something of a void out here that hasn’t really been filled with an emerging art scene.

How would you characterize the East Hampton arts community? Does it make sense to talk about there being an art scene in the Hamptons at all?

HS: It’s funny, as I’m saying “art scene” I’m not sure if that’s even an accurate way of describing it. It’s definitely been evolving, especially this summer. I’ve had a number of people come into the gallery who have structured their day around going to shows in the area. They’ve also commented that they’re almost surprised that they could spend a whole day like this—that there were actually a number of shows that they wanted to see.

I think it is changing and evolving out here, which is nice. That being said, if you’re thinking about something like the New York City art scene, we don’t have that here. I think the whole notion of a scene in the Hamptons is something else entirely. We’re just sort of doing our thing.

On that note, what would you say characterizes your program?

Ryan Wallace: There have been great galleries out here for a really long time, but generally it was people who were further up the food chain, with a lot of secondary-market stuff and otherwise much more established artists. It kind of goes with the nature of how ostentatious it can be out here [laughs].

Our idea really came about because we knew that our peer group at the time wasn’t going to be getting shows here, but we thought that it would be appreciated by the community if their work was put in front of them. Since we already had ties in the area we were able to do that without a huge financial investment, which I think has prevented people in the past from even trying.

People would come in who had maybe heard of certain artists we showed, but who didn’t make it to the Lower East Side. It was a way to make it really easy for them to see stuff that we thought they’d like that they hadn’t seen in person yet, and to do it in a typical white cube gallery setting. Some of the other places out here that I really love, like Fireplace Projects for instance, have great programming, but what really makes it cool is that it’s set in an old garage. That’s been the model out here. We wanted to give our community a formal setting out here, combining the two modes.

Installation shot of works by Keegan McHargue

Installation shot of works by Keegan McHargue

Can you tell me a bit more about your peer group? What approaches or ideas bring you together?

RW: Well, Hilary and I went to high school together, so that was easy. I went to RISD and she went to SVA, so our original groups come from those places. We’re really an artist-run space. We didn’t have collectors, we didn’t have a super social network, but we did have a huge network of artists who we thought were really interesting. They’re not bound by one aesthetic or one field—we just thought that they were doing interesting work.

We knew what the first two years of programming would be pretty easily, and when that happened people were like, “Do you know Kate Shepherd?” or “Do you know Nayland Blake? I had him as a teacher.” These really simple introductions gave us the ability to meet older artists who saw what we were doing as kind of pure and were excited to work with us. I wouldn’t say that it’s about a single sentiment or aesthetic—it’s more about what we think is exciting, in whatever media.

How did you go about cultivating your collector base to keep the business going?

HS: Honestly, that part was almost equally organic.

RW: I’d say two things happened early on—people just stumbled into the gallery and bought work who we later found out were huge New York collectors, and some artists that I went to school with were gaining critical and collector momentum which meant that people followed them.

Now, art fairs and the Internet have really made this sustainable. We wouldn’t have been able to get by with just those things, but now we have people in Denmark and Los Angeles and Texas that buy from us. I think 10 years ago, it wouldn’t have been possible out here.

HS: Again, the location really worked to our advantage. There wasn’t a huge amount of competition, and it wasn’t necessarily on people’s agenda to go to a gallery when they come to the beach. It ended up being part of their experience when they went to town, and people were pleasantly surprised by what they were seeing. There was a word-of-mouth effect that came with that, and I really see our location as what propels us into having success early on in terms of our collector base.

Installation shot of works by Tim Bergstrom

Installation shot of works by Tim Bergstrom

The Hamptons have a long and storied history as an art-world refuge from New York. Why do you think this connection was and continues to be so strong?

RW: The light—it’s all the typical romantic clichés.

HS: People really do talk about the aesthetic experience of being out here—the light, the beauty. The first en plein air school was built out here in the Shinnecock Hills by William Merritt Chase [the Shinnecock Hills Summer School, opened in 1891], which was obviously centered around being outdoors. In a sense, it's the same draw that brings people from the city out here. There’s an escape-like quality paired with the natural beauty. And again, while it is a cliché, the light is quite unique.

RW: That’s what has always brought artists out here, and then other people follow artists. One nice thing about being out here that I assume goes back to the ‘50s, when what we could call an art market developed, is that when people come out here they definitely let their hair down. It’s not the rat race and competition of the city, for artists or for gallerists.

That said, here you can have real conversations about art with people who are knowledgeable and genuinely interested. In other rural areas that I grew up going to, you don’t get that. You might find one or two people like this, but it wouldn’t make for a sustainable business model. That’s pretty unique to here—artists are drawn in so they can work, people are always enamored with the social status of being down with artists, and the proximity to the city makes it a perfect little storm for real art dialog to go on.

You mentioned the importance of art fairs and the Internet for sustaining your business. In our digital era, where install shots go up online almost as soon as the works are hung, is location really important for a gallery? Do you have many collectors buying off of jpgs?

RW: Yes, but it’s generally always been people who have met us personally or have seen the artist’s work in person at some point. We definitely have never had a run of people buying a bunch of works by an artist because they think they’re going to be the next big thing. It’s just never happened. I’ve never sold a piece off Instagram, ever.

Once the connection to the work or to us personally is made, trust is built and we can say something like, “You loved this artist when we met you in Dallas, we have a new one that we think is really great.” We have one collector who I usually walk through a show for 40 minutes or so over the phone, just describing the way the light hits things. It’s not as easy as sending a jpg out and having people say, “I’ll take it.” The Internet provides access for people who don’t have to be in here for every show, which is based around trust in what we do and what we’ve chosen to show so far.

How do art fairs fit into all this?

HS: I would say that art fairs have been more valuable and more important to us then selling online. In my mind, it plays into our location. There is a limitation to being where we are, in that it’s primarily a New York collector base that comes to us. It’s not the international location that New York City is, so there are less people who come to see what we do. Art fairs have allowed us to expand our collector base and the people who see the work.

RW: There’s also a mental trick that happens to people in that setting that just sparks commerce. When people come in here, we just talk about the show and the work—if they’re going to buy it, they’re going to buy it. At an art fair there’s really a mindset of commerce. That may be cooling, but I don’t know—people are really ready to pull the trigger in that setting.

Untitled 1 (2016) by Keegan McHargue

Untitled 1 (2016) by Keegan McHargue

It’s interesting that both of you are trained as artists. Many artist-turned-gallerists talk about their space as a kind of extension of their art practice. Is this how you think about running Halsey McKay?

HS: I’ve had a lot of curatorial experience, but I think I identify more as an artist in my approach to things. For me to be doing something like this, I need to feel that it is an extension of a creative impulse. The whole idea of what a curator does is definitely shifting, but I don't really identify with it. The experience of running a gallery very much feels like I am using the same muscles as when I was making work on my own.

All the shows we do and the artists we seek out start with an emotional or visceral response, then intellectual inquiry—a studio visit—and grow from there. I've always been working with physical space, how to modify it and be sensitive to architecture, the placement of objects and how its effect the way we see and experience things.

When we have big group shows the overarching idea generally comes from Ryan, which is very curatorial, then we riff off each other from there. I’m more interested in the two-person and solo shows we're doing because of the intimacy of working closely with someone. I just associate it all with the fluidity of creativity—maybe that’s more closely linked to curatorial work than I realize, but that has been my experience. The business side is of course more structured and I love that too. Plus, there’s so much psychology involved with selling art. It's fascinating.

RW: For me, the two things are pretty different. It came out of just going to a lot of shows like every artist does and seeing connections between artists. I found myself thinking, “Woah, it would be cool to do a show with those three artists.” This became an opportunity to actually realize ideas like that.

It really has nothing to do with my time in the studio, which is pretty straightforward, stereotypical artist stuff like staring and moving things around [laughs]. I’m interested in economics and how a small business works, but my art practice has nothing to do with those things. I’ve always been pro-job because I don’t want commercial pressure on the work to produce this or that thing and I’m not really into branding myself. This has been a way to spread awareness about myself and my practice without talking about myself. It just kind of happens. I benefit from it just from relationships that happen as a result of doing this, but there’s not a conscious connection between the type of work I make and the type of work I want to show.

Even when I first started, I was always interested in artists who did things like run a publishing company or curate shows, rather than just constantly being like, “Look at my work, give me a show.” It’s really easy for me to brag about my friends’ work, not because I’m not confident in my work but because I’m just not interested in going to openings to push my own agenda. It’s all one thing, but intellectually they’re totally separate.

HS: I will say that Ryan is a practicing artist—I am not. That’s the divide in perspective. I’m not in the studio making work. This is what I’m doing with any creative impulse I have right now.

You two have known each other for a long time. How would you characterize your working relationship?

RW: Sibling-like? [Laughs.]

HS: Yeah, probably. That’s how other people have characterized it.

In a good or bad way?

[In unison]: In a good way!

RW: It’s nice knowing that the other person isn’t going to run away with the money [laughs]. There’s a lot of stuff that we’re able to just take for granted.

HS: There’s definitely a lot of trust, and there’s a natural ease that comes with that. I think the sibling aspect of that is that you can be really open and honest and not have it turn into a deeply personal thing.

The division of labor came pretty naturally according to the skill sets we already had. I had been an administrator at galleries before, so I ended up doing the administrative side of things here. All those things just fell in to place.

RW: I had worked as a graphic designer for 10 years, so I knew how to do all of the web stuff. We had a lot of different skill sets that made opening really easy, and otherwise it was YouTube and Home Depot.

So many other gallerists we talk to are like, “What the hell?” when they find out how little money we started with. We’re like, “Well, we built the walls and did the website ourselves, and Hilary already knew how to run a gallery.” It was just really low-risk—we could lose all the money we were putting in. It seemed plausible that with no experience or Rolodex we could make that money back. It worked, and we liked it.

Green Devils (2016) by Tim Bergstrom

Green Devils (2016) by Tim Bergstrom

You mentioned in an earlier interview that you put on some 23 exhibitions in 2014, an insane number by anyone’s standards. How do you do it?

HS: We just work all the time [laughs].

RW: Through sheer moxie [laughs]. We’re way ahead of schedule with the programming. Next year is not quite done, but we have a pretty good idea what it looks like. Outside of the summer we do longer, four-to-six week shows, so it’s not always so crazy.

What’s the rationale behind this rapid turnaround?

RW: It’s about consolidating the eyeballs out here. The people who are going to see the shows see them within those three weeks, so having a six-week show wouldn’t benefit the artist any. It’s also a conscious effort to expand the circle a little bit with each show, to get a little more word of mouth going. It’s an affordable way—although maybe not time-wise—to do that, rather than hiring PR. With each show there’s more momentum, and the word spreads faster. Now, though, I don’t think we need to have such a grueling pace at this point. People are aware.

How do your offsite projects fit into the rest of what you’re doing?

HS: It’s a way to have a presence in New York City and a way to test the waters.

What kinds of offsite initiatives do you have going now?

RW: We did a show at the Elaine de Kooning House earlier this year. We have a relationship with the owner of the house through the Dallas Art Fair. He has this gorgeous house that we always went to because he would have these very informal residencies there. No one wanted the residency in the winter or the spring, so we thought we could do a show there. It’s become, possibly, and annual thing—we’ve done two shows there.

This week, we’re opening a show at 1430 in Portland, Oregon, which came about because we get along well and share similar artists. She just asked if we would curate something for the space. We also have an ongoing show of work by Matt Rich at 56 Henry up through August 15th. It’s hard to say no when opportunity arises. As an artist myself, I just want to give people shows.