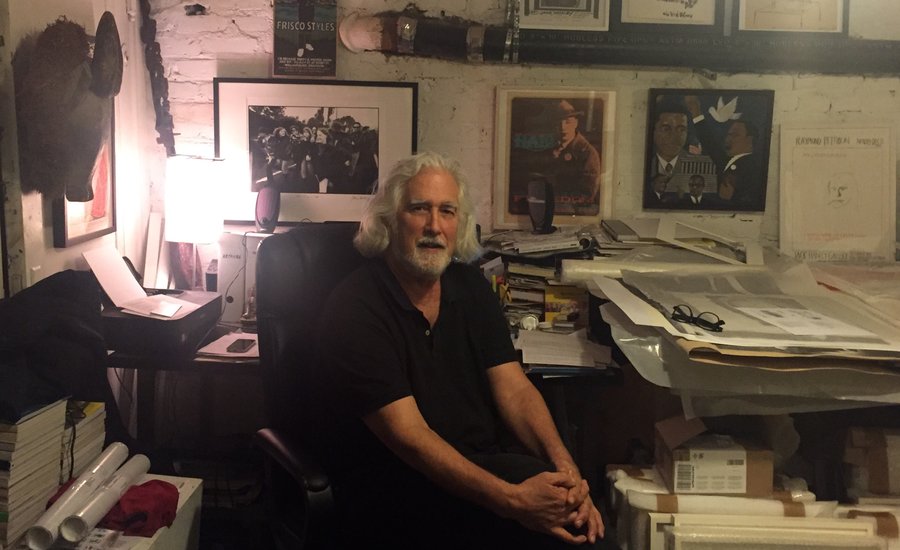

Working out of a basement office two flights below his spacious gallery on Broome Street, Jack Hanley orchestrates his continually exciting program from a desk surrounded by row after row of shelves groaning with art, music posters, and assorted memorabilia—a setting that brings to mind the warehouse where the Ten Commandments are stowed at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. A former roadie for the Grateful Dead who has had galleries in four cities, taught at Princeton, paints on the side, and raises orchids for fun, Hanley has come across this trove of memories honestly. And, boy, does he have stories to tell.

For the latest installment of our ongoing NADA Network series, pegged to this week’s edition of NADA + ART COLOGNE COLLABORATIONS, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein sat down with Hanley, a Washington Heights native whose cumulus-cloud beard and easygoing, sunlit demeanor have helped make him one of the best-liked fixtures in New York’s art world.

His daughter, Emma, who works in the gallery, says he’s working on a book. It's a good idea. Here’s Hanley on why art fairs are like music conventions, how a love potion changed his life, and how Instagram is revolutionizing the way art is being made today.

You have quite the unique backstory for a New York art dealer. For one thing, you started out touring with the Grateful Dead, working as the guitar technician for Bob Weir. How did that happen?

Well, I played in bands when I was young, and when I went to college I got a job booking concerts for Binghamton University. In the process of doing that, I booked the Dead and all kinds of other big acts to play in the gymnasium, so I got to know the band. I was also going out for a while with a woman who worked as a road manager for the Dead and ran their tours. She was from the Bay Area, and I knew her because she would also bring the Sons of Champlin and the New Riders through Binghampton, since they were all run out of the same office in Marin County.

So this was not only your introduction to the Dead, but also to the California vibe.

Yeah, that was my motivating factor to go out West and get work. I thought I’d keep doing things with bands in one way or another. The Beach Boys offered me a job after I booked them, too, to drive their Winnebago or something. It probably would have developed into other things, but my dad wanted me to finish college first, which is probably wise.

What were you studying at Binghampton?

I was a Native American studies major and took a lot of film classes, but at the very end I started to study painting. I had never studied art—we didn’t even have it in my high school. I only took it at the end of college because I liked this woman, and she was in the painting class, so I just thought I could hang out and stare at her.

The same Grateful Dead manager?

No, some other woman. So I started painting there. Then, I went out to Marin. It’s the first place I lived in Northern California, and I just started working for the Dead when I arrived out there. This would have been in the early ‘70s.

What exactly did you do with the Grateful Dead?

Guitar tech. It was pretty cool. It was still prime Dead. Pigpen was still alive. This was before we went to Europe, right around the time of “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty.”

So you were working with Bob Weir, setting up his guitars while out on tour. Were you still painting on the side?

No, I didn’t really paint too much—only when we weren’t on tour, and they were on the road a lot in the early ‘70s. At first, I was torn about how serious I was about art, but as I did it more I grew more interested and decided to apply to grad school at Berkeley, to get an MFA and an MA in painting. I actually met Joan Brown, who was teaching there, and her son was a Deadhead, so she helped me get into Berkeley or at least opened the door, because I didn’t have a degree in art.

That’s hilarious that your Dead connection got you into the MFA program at Berkeley.

It is hilarious. That’s a good way to put it. It’s hilarious. Not that some of the people around the Dead weren’t educated in some ways, but it was a different world, that’s for sure. I didn’t go to Berkeley immediately, though—I worked with the Dead for a few more years, and then went at the tail end of that, maybe ‘79, ‘80.

Who did you study with at Berkeley?

Joan Brown and Elmer Bischoff and Peter Voulkos and a bunch of other people. But I was a TA for Joan Brown for several years.

It seems a theme is beginning to develop, of women being strong forces in shaping the course of your life. What was Joan Brown like?

She was a big influence. She was really into Indian and Egyptian and Peruvian philosophy, all these cultures that had a great deal of appreciation for the spirit world, and it pushed my painting. Joan was good in terms of teaching you to trust yourself, that it’ll go to a good spot. That freed up my painting a bit—not fretting over what direction it was going in.

What was your painting like?

At the time, it was pretty abstract—large oils, process-oriented. Kind of like de Kooning on acid. Really explosive. I would draw figures, but then I would turn the canvas and they would get obliterated. I don’t know, I like them. They seemed to get better as I went along.

Did you show them anywhere?

Yeah, I showed them at the time, mostly in the Bay Area at a gallery called Hansen Fuller. I was still hanging out with the band, too, but then I started seeing this woman who was a student of mine at Berkeley, and we ended up living in Italy and getting married. She didn’t like the Dead or the women around the band, so that kind of put an end to my Deadness. Well, not in my own head, but it did in terms of my behavior.

I suppose going to Italy is a pretty good way to get you away from the groupies.

Yeah, were were pretty much left all to ourselves there in Tuscany, out in the middle of nowhere. I had sold a few paintings for $4,000 and rented a place for $400 a month, and that pretty much got us through the year. I was just painting out there, and she painted too.

How long did you stay in Tuscany before going back to the U.S.?

Oh, just a year. We went back and moved to New York briefly, because I sub-letted a shitty little apartment from this guy in the Psychedelic Furs, Richard Butler. I then decided I’d try to get a teaching job, so I got one at Rhode Island. While I was there I met someone whose boyfriend was P. Adams Sitney, a big film critic at the Village Voice who taught at Princeton, so she recommended me for a job there. Then I taught at Princeton, and I met a woman who also taught at UT, the University of Texas at Austin, so I then got a job teaching there for six years. While I was in Austin, I opened up a gallery.

What led you to do that?

It’s pretty weird. I never even liked galleries. And even as a painter, I could hardly ever get paid wherever I showed, and some people just kept my work. I wasn’t business-oriented in the slightest. But I had started collecting stuff. At the time, you could fly from Austin to New York direct and it was pretty cheap, so I’d go to New York a lot—Austin seemed really small—and I’d just rummage through the back rooms of different places and buy prints and works on paper, because it was the first time I had some money to buy stuff. Then, my friends in Austin who I would play music with would ask to buy them from me.

The next thing I knew, I was buying three or four of an edition from Brooke Alexander or someone else, plus drawings. I got a flat file to store them in at my house, but then my wife got pregnant and she wanted a real bedroom, so I had to get my art shit out of there. At the same time, I would always be telling my students to go look at shows, but I realized that they were never going to see anything, because even through there were a couple of local galleries, they didn’t really put on shows.

So I decided to start one. I rented a space for $400, and asked a student of mine, Angela Choon, if she’d sit there and watch the place. She now runs David Zwirner’s London gallery.

Who were the artists you worked with there?

I was showing people from New York and Europe that I knew, and would invite them down to stay in my house and do a show. They were good artists, like Günther Förg and Christopher Wool.

And your clients were mostly people from the Austin music scene?

Yeah, and faculty at the university. The museum also bought some stuff, and there was this one guy, John Parker, who would come and buy the best work out of every show. But basically I had about four clients, and nobody came to the gallery—I mean, all of my students would come to the opening and drink my keg of beer, but that would be it for the month.

This is around when you started doing art fairs, is that right?

Yeah. I had all this work left over at the gallery, so I got a U-Haul trailer and put it on the back of my Volvo station wagon and loaded my Chris Wools and Gobers and assorted drawings and all this crap and drove it up to Art Chicago in ’87 or ’88. I made $80,000. I thought, “This is fucking awesome.”

I don’t know, I had never done an art fair before. I had done some entertainment conventions—actually, that’s where I had met Julie Salles, the Grateful Dead tour manager. When I was doing concerts for Binghampton I had gone to an entertainment convention in Cincinnati and smoked DMT with her and the manager of the Band. So I knew that kind of convention, but Art Chicago was the first time I’d been to one that was not musical.

After a few years in Austin, what inspired you to pick up and move your gallery to San Francisco?

Well, we had a second kid, and I think my wife wanted to be around her family, which was a big family in the Bay Area. So we moved back so we could get divorced.

What was San Francisco like?

I had been to San Francisco a few times when I was younger—I had hitched across the country three times—and I had those shows at Hansen Fuller, so I knew some people. But now, when I moved back in ‘90, all the artists I knew had galleries, so I showed more of the artists I had down in Austin. I found the space for the gallery by looking in the classifieds, and my first show was Stephen Prina, Sophie Calle, and Tim Rollins & K.O.S., then the next show was Christian Marclay. It was people who are big now, but at the time they were still small—I just knew them. I knew Christian through music, mostly. He would cut up records and glue them together and then he’d play them, but I liked them because it would be an object.

With your music background it seems you would be the perfect dealer for someone like Christian Marclay.

There’s often been a lot of music connections to the people I worked with. Not always, but often.

What was the reception like for your gallery like among the San Francisco collectors?

Well, I was married to a woman from this prominent family, so people sort of assumed that that helped me, but it didn’t help me at all. I didn’t show the kind of thing that they or their crowd liked, because I was showing weird people like Karen Kilimnik and Ray Pettibon, and these were not the kind of artists that conservative people in San Francisco collected at the time. So that’s when it sinked in that I should try to do more art fairs.

I guess it shouldn’t be a surprise that you were a fan of art fairs from early on, considering it’s pretty much the same thing as doing a musical tour.

It was a really familiar thing for me. Even now, setting up a booth when there’s no crowd there, taking it down, doing all the different hotels, I sometimes think, “Oh God, this is just really familiar....” So, no, it wasn’t a big jump in my head to keep doing fairs.

In 1992, you even traveled to Cologne to do the first edition of the (UN)FAIR, the experimental alternative fair that pretty much gave birth to the entire alternative-fair format. What was that like?

The concept behind it was that, basically, Art Cologne was this old fair, and it was run by this association of German galleries who wouldn’t let in any of these younger, cooler galleries. I used to go there all the time in the ‘80s, when it was still the big, cool fair, but by this point there was no notion that having younger galleries at the main fair would even be a desirable thing.

So, the dealers Christian Nagel and Tanja Grunert decided to organize the (UN)FAIR as a place to show these other galleries. They knew a lot of dealers, but because they had galleries of their own they couldn’t devote themselves to doing a fair along, so they hired a woman named Heike Kempken to be the director. She had done some things for the Venice Biennale, and she'd been together with Jay Jopling.

It was very cool—it was located in a Deutsche Bank from the ‘70s or something, a really weird looking building, and it had a bar in the middle that had rows of booths radiating out from it, like the spokes of a wheel. Pat Hearn, Colin de Land, and all these people did the fair. Lisa Spellman was right across from me, and Kim Light also had a gallery there. I remember I brought Jack Pierson and Nayland Blake. It was a good fair.

I’ve heard you have an interesting story from the first (UN)FAIR that involves a love potion. What happened?

Well, when I was doing the fair, Carsten Höller gave me this drug that was a kind of phenylethylamine—he got it from Daniel Buchholz, who was selling these little vials for $80 at his booth related to sex and the Summer of Love and all of that. You didn’t drink it—you would just smell it, and it would supposedly give you the same feeling of being in love, synthetically. Anyway, I kept it on my table, and I kept giving it to Heike, the woman who ran the fair, and the next thing you know, we had a kid. She’s at Syracuse University now.

Wow, it sounds like the drug worked.

I thought it worked. I mean, it wasn’t like you got a buzz, it kind of altered something. And I had a friend who seemed like he was going to get a divorce, so I gave him the rest of mine, and he and his wife are still together.

What transpired after the love potion incident?

At the end of the fair, after hanging out with Heike, I said, “You should come visit,” and two weeks later, she was like, “I’m at San Francisco Airport.” We hung out in Berkeley and in San Francisco, and we organized a fair together in San Francisco at the Phoenix Hotel in ‘95.

Where did the idea for that fair, the which you dubbed the San Francisco Art Fair, come from?

Well, Heike couldn’t work in the U.S. because she didn’t have the proper papers, but she knew how to do fairs, so she and I just concocted it so that she could come up with some money to live on in order to not feel dependent. Also, at the time SFMoMA was opening a brand-new museum—which it so happens they’re doing again now—and we figured that it would be an opportunity to show all of these people coming into town something different. But it was fucked up because my mother-in-law was the head of SFMoMA’s board, and she saw this as an attempt to upstage the big opening of her museum. I was still getting my divorce at the time, too, so it was really intense.

Why did you choose that hotel?

I was living in the Phoenix Hotel while going through my divorce. It was where all the rock people stayed, and it was in the Tenderloin, a really bad neighborhood. I used to play at a bar there, the Blue Lamp, which was a blues bar full of hookers. It was really hilarious. We got really good galleries to come there for the fair.

My in-laws took it personally, though, so they started telling dealers to not do the fair, and some people like Andrea Rosen and Barbara Gladstone bailed. But everybody else came—Jay Jopling, Lisa Spellman, Gavin Brown, Blum & Poe, Daniel Buchholz, good galleries. And Richard Prince, Jack Pierson, Karen Kilimnik, and Mike Kelley all did posters for me to promote it. It was cool.

Richard Prince's poster for the San Francisco Art Fair

Richard Prince's poster for the San Francisco Art Fair

Was it successful?

No, not really. I don’t know if people did really well. Gavin did alright. I mean, I did a huge dinner and introduced them to all my collectors, and they stole them all.

Let’s talk about your program itself a bit, which has included some extraordinary artists—including quite a few stars that you discovered, like Tauba Auerbach. How do you gravitate towards a particular artist? What do you tend to look for?

It’s just gut-level instinct really. It’s not commercial instinct. A lot of the time I’m drawn to stuff that I want to grapple with, or don’t really understand—if I get it off the bat I’m not really that interested. I like stuff that I need to try and sort out and see what it does to my head, that I need to spend a month with, or own. Often, artists are good sources of turning you onto somebody else, if they know you well. But in terms of common denominators, music has been one and humor has been one.

How does the musical connection work? Because none of your artists seem to work explicitly with music, like a Christian Marclay might.

Maybe not so much at the moment, but a lot of the artists I’ve shown are musicians. There have been other threads as well. Like, in San Francisco, I think people saw what I was showing as slacker art, and that the artists were working with ephemeral, shitty materials—like Pettibon’s work was pinned up, Jack Pierson’s photos were pinned up, and Karen Kilimnik’s stuff was basically ratty installations. People thought that was my aesthetic, but I was actually really drawn to conceptual art, so I saw this work as more lyrical in a certain conceptual way, but not dry.

After a while, I started showing more people who came to be known as the Mission School, like Chris Johanson, Barry McGee, and Alicia McCarthy, and all of these people who I had known from before but who had their own galleries. I didn't try to steal them from their other galleries, but slowly they worked their way into the program, and people started thinking that I was a Mission School dealer.

The thing is, all of these people played in bands, and at every gallery opening we’d have a band, and I’d put out CDs. I have a natural affinity for musicians, maybe.

Well, music is a great way for lots of different people to come together. I’m sure it’s no different in the art world.

Moving from one to the other was just an organic thing for me anyway. And I think some artists are just drawn towards a community, and San Francisco is a little bit like a clubhouse. For a while, I actually had a guitar store with my brother in Oakland, which was definitely a clubhouse. We’d have the walls full of guitars, and we’d mostly repair guitars for bands when they toured through town. But everybody hung out there and played music. The gallery was the same kind of thing, in my mind. Some of the artists liked that, and some of them didn’t like that.

In the early 2000s, you expanded your gallery to Los Angeles. Why?

Between ‘96 and ‘98, I closed the gallery and only did the guitar store. When I reopened, I moved from downtown to the Mission District, and nobody even came by. Really. I would just go for lunch and stay two hours at the French restaurant and come back, and no one would notice.

Eventually, the guy next door moved out, and I took over the space, thinking I’d use it as an office. Then Keegan McHargue and other artists started doing stuff in there, and I started thinking, “If was going to have two spaces, they didn’t have to be next to each other—one of them could be in another town.”

Well, I like playing music with my friends in L.A., so I typed in “Chinatown” on Craigslist and one space was available. I called the guy, and I knew him—he used to have a gallery, Dan Vernay. So I rented that space for $1,200 a month in Chinatown, and I would just go back and forth.

I had that space in L.A., at the same time as the one in San Francisco, for four years. It was great because I would play music with all these people. My friend Steve Hanson, who does China Art Objects, was part owner of the Mountain Bar with Jorge Pardo, and upstairs we would play every night. Eventually we’d moved it over to Joel Mesler’s little studio, and me and Joel and Henry Taylor and Steve would just play every night. It was so fun.

Anyway, my friend quadrupled my rent, so that’s when I thought, “Maybe I’ll just move back to New York.” Then a friend of mine in TriBeCa he said he could rent me the space below him for you for $3,000, which turned into $4,000, and that’s how I got to New York.

What was the transition to operating a gallery in New York like?

My idea was that TriBeCa was so out of the way that it would be the same as the Mission, and in a way it was as quiet, except at the openings. When I moved to New York, all of my artists already had galleries here, so I didn’t have any choice but look for new artists—which I like doing anyway. But it was much harder to find artists, and I felt more self-conscious about it than I ever had in San Francisco. It seemed to me that there was more media here, more critics, and more people competing for the same artists, trying to take your artists. So that’s when I started thinking that I just wouldn’t worry about it, and go around to see what I could see.

Who were some of first artists that you found for your New York program?

Bjorn Copeland, who’s a musician, and who I had shown in San Francisco. Margaret Lee, too. I would go to her soirées on Canal Street [for her own gallery, 47 Canal]—people told me that I had to go to that party, to see the group shows she was doing there. She maybe has sometimes too much going on, but: triple threat. She seems to manage it so far, too.

Now that you’re in New York, are you still playing music?

Yeah. I still play with Phil [Grauer] from CANADA, Tyson Reeder, and Michael Mahalchick. Mostly rock, country rock, blues. We don’t really have a name, but we go sort of by the Honey Badgers, and we play in CANADA’s basement next door every Thursday. Tyson plays drums a bit, and guitar. Phil plays keys—he’s got a bunch of keyboards—and Mike Mahalchick plays a baritone guitar and sings and chants poetry. I play guitar.

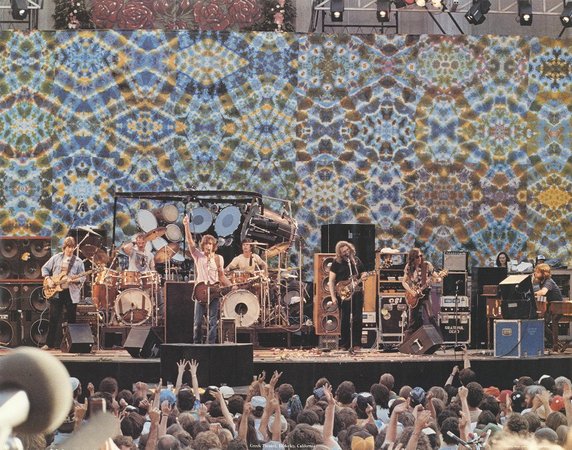

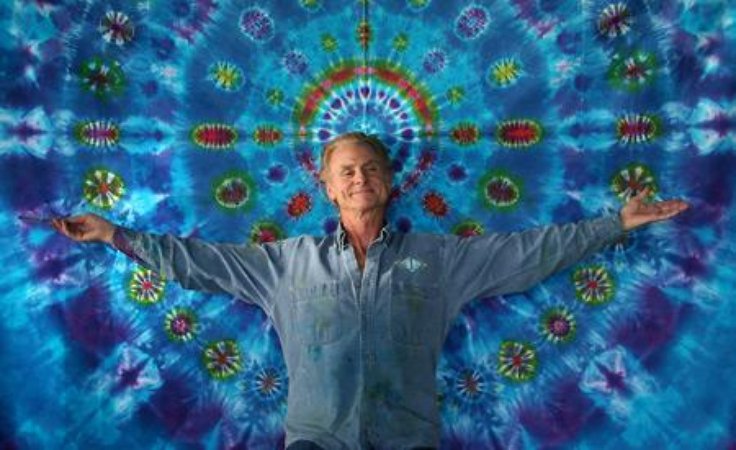

I have the mics and everything, and I just bought little PA and a bass amp and a bass to bring to band practice, but nobody plays bass. It’s pretty loose. I’ve brought in all these huge tie-dyes I have from the Dead years that Courtenay Pollock did. And, it’s great—we just drink beers, smoke pot, and play noisy music.

Above, one of Courtenay Pollock's Grateful Dead sets; the artist himself below

Above, one of Courtenay Pollock's Grateful Dead sets; the artist himself below

That sounds so fun.

It is fun, and it’s exactly what we did everywhere I’ve been: San Francisco, L.A., everywhere. Different people have different levels of talent, but it’s still fun, usually.

I guess when you think about it that way, of all these musicians scattered among the art people, an art fair is kind of like a secret music convention. Do you play on the road as well?

They are kind of the same, because when I go there I usually bring a guitar and end up playing with people that I know. Like, in Cologne, Haus Töller is a big place to hang out. The guy grew up with David Zwirner and he’s completely connected to the art world even though it’s a totally not hip place. I mean, it is hip, but it’s like from the 1500s. You can just go in there and find people.

Doesn’t David Zwirner play drums?

Yeah, he’s a pretty good drummer.

Have you guys jammed?

Yeah, many years ago, though. Pascal Spengemann is another one who’s a good drummer.

This idea of the art-fair-as-secret-Coachella puts an interesting anecdote about you in some context. In his great “Confessions of a Justified Art Dealer” series for ARTnews, Joel Mesler wrote: “At the Armory Show in 2007, I saw the dealer Jack Hanley running down the aisles of the art fair with a bandana wrapped around his head and his arms sticking out, like Frankenstein’s monster. I asked him what was wrong. ‘Nothing man,’ he said. ‘I’m on acid.’” Is that really something you do?

I mean, I’m not necessarily saying it’s a great idea for other people, but it makes it fun for me.

Do you still go to concerts too?

I still hear music almost every night. I live in Red Hook, and one of the reasons why I moved there is because I used to go and hear music in Red Hook all the time, and I thought this way I wouldn’t have to drive. Right near my corner is the Jalopy Theater, and next to it is a bar, and there’s live music every night in both. Sunny’s has live music too. Last night I went to see [‘70s Krautrock band] Faust at the Market Hotel—Heike used to date their lead guy. They’re pretty old, but it was fun.

Nowadays, in addition to music, there seems to be a new current going through your program, and that’s technology. Instagram, for instance, seems to be a very useful tool for you.

That’s how I found Alpha Channeling. I never even knew if it was a man or a woman when I offered him a show.

How did you find his work?

I think I just stumbled onto it. I don’t remember—I’ve only been on Instagram for about a year, but maybe somebody told me that I should check it out. I know Jerry Saltz is really into the guy, but I found out about that later. They’re just totally peculiar drawings.

But Alpha wasn’t really interested. I wrote to him for the whole year, and he never answered. Another guy who has a gallery told me forget it—he tried for a year and a half or something. There were a few other people I was going for, too, like LSD Worldpeace, who's a guy Alicia McCarthy is friends with and who I tried to show. He agreed, but then stopped answering emails. They’re really great drawings.

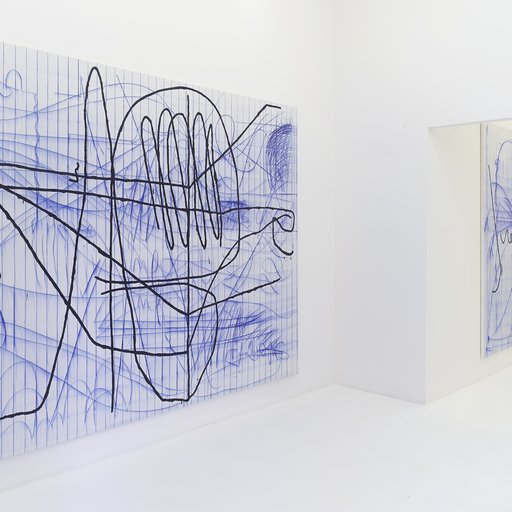

A piece by Alpha Channeling

A piece by Alpha Channeling

Why wasn’t someone like Alpha more eager to show with you? He wasn’t interested in selling his work?

No, I think he lives off of it, but only through Instagram. He does a lot of prints and drawings, and has a vast following of people—I mean, he’s got 220,000 Instagram followers. It kind of reminds me a little bit of when I first showed Ray Pettibon’s drawings at $100 each, and people who look like they had never gone to an art gallery would come and spend two hours looking art them. There are people who are really into Instagram as an experience, you know?

And you couldn’t tell if Alpha Chanelling was a man or a woman because he only goes by his Instagram handle, right?

He didn’t want people to know his name, or if he was a man or a woman. On the day of the opening he said he’d come by and say hi, and so people would come in and Brandy [Carstens, Hanley's gallery director] and I would go, “I think that might be the guy,” because the guy would look kind of sketchy. But when I met Alpha, I couldn’t have been more surprised—he seemed like my son, you know, a healthy, normal-looking person. It just seemed kind of hilarious. He was born in Switzerland, and he told me that he does other things, too—he has other accounts on Instagram that uses to show different things.

Like different styles of art?

I think so. He seemed to get nervous when I asked him too many questions about it, but I think he has maybe a separate career in a certain way.

So, how did people respond to your showing an Instagram phenom in your gallery?

We’ve sold most of them, and not to people from Instagram—although it seems like a lot of people came through that too. It’s interesting if something that’s successful on Instagram crosses over like that. It’s weird—it reminds me that Second Life was big years ago, and I knew people in Berkeley who lived off of playing music in their bedroom and beaming it into a café in Second Life. One of the guys would play there as a girl folksinger, and they racked up all these coins that they then transferred into dollars.

It seems like the evolution of technology sometimes don’t go in a direct line, but it would be funny if people end up liking the digital artwork more than the object thing.

Well, that’s interesting, because thus far the quality of art as a unique, auratic object that you have to experience in person to truly appreciate is what has allowed the industry to elude the same kinds of disruptions that we’ve seen in the music industry and media, where all of a sudden fewer people are interested in buying the expensive CDs and newspapers that used to be enormous profit engines. Do you think the gallery experience is still essential?

I mean, hopefully it is. But, well, there’s an artist from New Zealand who came by the gallery today and was saying how Alpha’s work is almost disappointing in person compared to how it looks on Instagram. I don’t know if it’s the compression of the image, or the size, or the way it’s lit, but it’s different. And it’s a more intimate experience seeing it on Instagram—like, you’re alone in your bed. And some artists tailor their work to these kinds of conditions.

How do you mean?

Well, I remember when electricity was really expensive in Europe, so people got into having fluorescent lights in their studio. The next thing you knew, it permeated into the galleries, and then it made its way to New York, where the galleries all used to have halogen lights—but when the artist was making their work under fluorescent lights, it was much better to show it in the same way that it was made. Just like when people recorded on vinyl, they balanced it differently. It's the same thing with Instagram. If you’re making art, and you know that your main audience is on Instagram, then there are certain things you can do that look good in that format.

It’s funny that you bring up the difference between the in-person versus the digital, because it's exactly what I was talking to the New Zealand artist about. And she said that a lot of people like her are really comfortable not having the in-person experience, which is different from how I grew up.

I mean, that’s the one thing I liked about Dead concerts. The music was certainly the motivating factor, but it wasn’t the only reason you had a good time there—the part about being around other people getting off and having a wonderful time and dancing around you was certainly as much fun. I think people still do like that. But I don’t know if art is as ecstatic a kind of experience, for the viewer.

I’ve seen a lot of art that looks better on my phone after I take a picture of it than when I actually look it in the space.

Yeah, me too. And I’m much more reticent now to think I know what something looks like in person from an image. You can’t really read the size, for one thing, and if you add in all the digital enhancements and photo programs available, the differences are greater now.

This digital direction must be at least somewhat appealing to you as someone trying to sell art—for one thing, you don’t really need to load up the van with work anymore if everything goes digital.

Actually, just selling something is the least interesting part of art, for me. It wouldn’t really hold my interest to try to set up a format to do that. If anything, the digital stuff just seems like an advertisement in some form. But, if you could set up a format to digitally give someone the same high you might get off of seeing something great in person, then that seems cool. Maybe it could shift to where the live thing is less satisfying.

I mean, I listen to digital music in the car, whether on a CD or streaming it in, but I still like seeing music live, and I’m a fan of mostly live things generally. That’s what I liked most about the Dead—it just seemed like it could go in any direction, you know? There was just an electricity in the air because it seemed like it might fail, whereas things that don’t have that failure aspect, generally, are more predictable. It’s not as fun.