In a city that’s suddenly chockablock with young galleries and new fairs, the two-and-a-half-year-old Super Dakota has managed to carve out an intellectual, art-historical niche. Founded by the Parisian Damîen Bertelle-Rogier, the gallery has built up a devoted following for its formalism-friendly, literary, intergenerational roster, which includes the young French abstract painters Baptiste Caccia and Hugo Pernet, the octogenarian German minimalist Joachim Bandau, and the late American still-life photographer Jan Groover.

If the gallery’s program is conversant with the past, its way of doing business is definitely of the future. Bertelle-Rogier, who started out working for music labels, wants to bring that industry’s standards and practices—in particular, its detailed contracts between management and talent—to the often vague, elliptical correspondence between artists, dealers, and institutions.

On the eve of Art Brussels, he spoke to Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg about his ethos of radical openness, how best to earn the trust of Belgium’s famed collectors, and why we need unsparing critics to keep the art world on its toes.

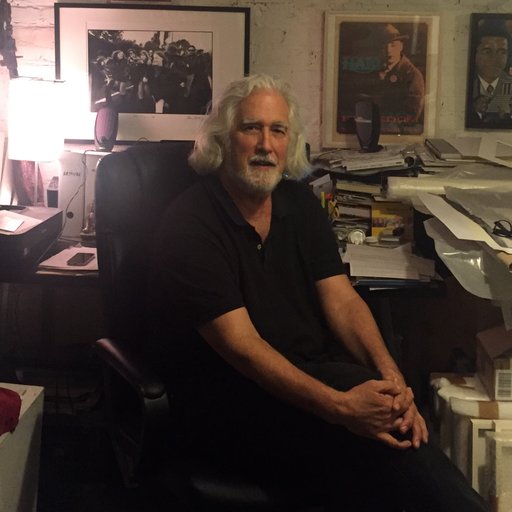

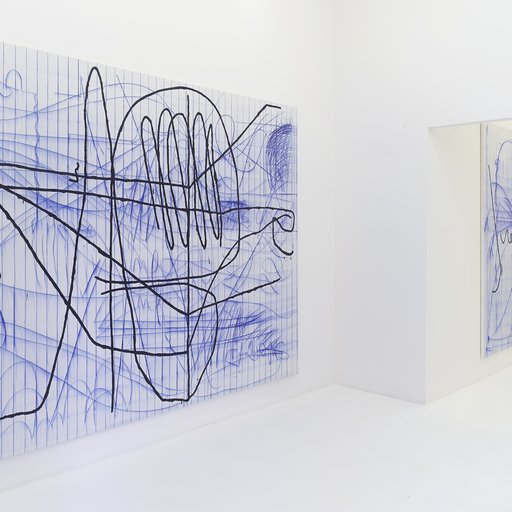

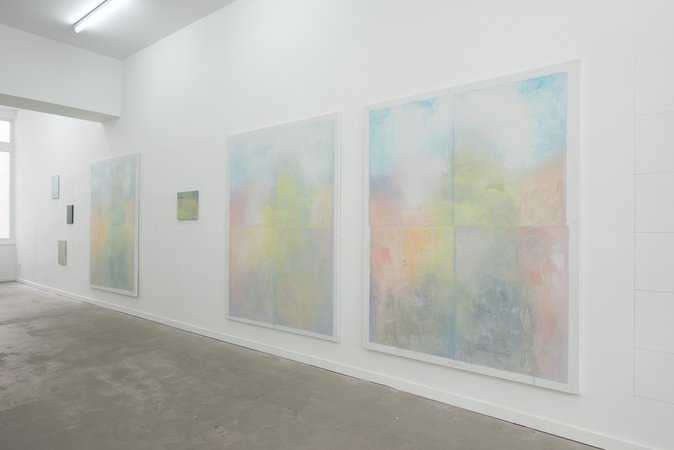

Installation view of the gallery's current show, Baptiste Caccia, "Veduta," through May 21, 2016. © Isabelle Arthuis, courtesy of the artist and Super Dakota, Brussels

Installation view of the gallery's current show, Baptiste Caccia, "Veduta," through May 21, 2016. © Isabelle Arthuis, courtesy of the artist and Super Dakota, Brussels

You’ve built up a smart, successful program in a short span of time, and I’d like to ask you how you did it. But first, since we’re on the eve of Art Brussels: What is the mood in Brussels right now? How are people feeling, in the aftermath of the recent terrorist attacks?

Well, of course everybody is talking about it—it’s a very emotional time for everyone in the city, and it’s been hard on everyone. But you need to keep on moving. Brussels is quite optimistic, in a way. I had a lot of conversations with people last night during the opening of our current show, and of course the subject came up. People said, “We need to keep on going.”

Is there concern about attendance at the fair? Are collectors from abroad changing their travel plans?

Well, of course we have clients from abroad who didn’t want to come anymore, because they’ve been scared. And you can’t really blame them. I assume it will affect the number of visitors in the fair. But we’ve also received a lot of support from abroad, a lot of messages from our clients and friends saying that they will come and look forward to seeing us. So it really depends on the personalities. You can’t expect it to have no effect on the visitors. It’s normal that people are scared, now, to come to Brussels, especially if you fly.

Where do most of the Art Brussels collectors come from? What proportion would you say are European?

It’s mostly European. There’s a great collector base in Holland, in Germany, and in France, which borders with Belgium. So of course we have a lot of them, but also English and Spanish collectors and some Italians as well. And then you’ve got some Americans, but I guess we will see less of them this year. But it’s all right. Brussels is a great city, and we have some American clients that always enjoy coming in for the fair, and they will.

You are from Paris—how did you come to be running a gallery in Brussels?

Yes, I was born in Paris. I studied the history of art and cultural management, but I had many different jobs. I worked for a while in the music industry, and this is where I got my management skills and got interested in managing artists’ careers. I worked for big labels, working with artists like Muse and other big names and some more underground French music. I worked with major music festivals and some smaller ones. I was 18 when I had my first internship, and I have done pretty much every single job that you can do in the music industry, from being a roadie to being A&R and artist management.

But I was always torn between music and art, and I ended up at some point working with some younger artists who were friends of mine and asked me to help set up shows, and working with galleries that asked me to look at contracts and things like this.

The gallery started very naturally. I had a project with a business partner in Paris—we created a sort of salon inspired by Gertrude Stein, called Apartment. We did this for a while, but I knew when we were doing this that I wanted to set up a proper gallery, because I wanted a space where artists could do new projects and hang a proper show. When you do it in an apartment in Paris, it’s a bit more complex and you don’t really have the freedom to install works as you would like.

What did you learn from managing musicians that applies to artists?

The thing I appreciate, that the music industry has but the art world doesn’t have, is that it’s a contract-based industry, so the relationships are quite clear from the beginning. That’s something I’m trying to bring to the art world, in the way that we work with artists, trying to make sure that all the relationships are quite clear from the beginning, that there are no flaws in our communication, so you can’t have hard feelings.

In the art world, people often complain that it’s very opaque and you don’t have the transparency of information. My point of view is that if you’re clear from the beginning and you maintain a flawless communication line with all of the people you’re working with—collectors, artist, institutions—if you’re very up-front with everything, it makes it easier.

That is certainly a big complaint about the art world, that it’s unregulated and that there’s a lack of transparency. So how do you create that transparency, on your own, in this very opaque industry?

It depends. For the artists, I don’t think you can have a contract that is valuable in terms of content—you can’t force someone to make you 20 paintings and expect them. I know some artists have contracts with people that specify like 20 paintings a year, but that’s just ludicrous to me. If you expect art to be done like this, I think you should start selling toothpaste! You can’t force someone to paint—I will never ask an artist for a certain amount of work. If you’re trying to push someone with a contract, saying you owe me this kind of work in this format, you’re just killing the creativity. You’re forcing them to make product, commodities.

In the end all you can do with the artists you represent is to be there, to make sure that you have trust—this is the strongest base you can have. That being said, we do have contracts, consignment agreements mostly, that we have the artists sign—mostly the ones we don’t represent, so they know that the work will be returned, they will be paid on time. That’s important, I think.

That’s not standard practice?

I’ve worked with a lot of different galleries, and had a lot of different experiences. We consign works from major galleries and I love working with big galleries, because it’s always very clear. Everything is in writing. But sometimes we work with smaller galleries, and you need to be very creative with them sometimes.

What about working with collectors? What does transparency mean to them?

With the collectors, it’s about being honest with the prices, being honest with what’s available and what’s not. I think it’s about trust at the beginning, and young galleries like us want collectors to support the artist’s development in the long-term and come back and buy more than one piece. Most of the artists we work with are quite young, emerging, so we need people to actually buy the vision and not just the work. I’m trying to be the most honest with them, and sometimes that means telling them not to buy a work, to wait for another one. You need them to trust you, so that when you go to them and say, “You need to buy this piece in particular,” they will trust your choice.

We don’t work with Picassos, pieces that are very familiar and easy to sell. We work with people that collectors have sometimes never heard of, or have seen here and there. It takes time to get acclimated to the work. My job, most of the time, is to trying to get them to understand what the artist is trying to do and where it’s going, because when you buy a piece from a young artist, you need to consider it not as a final product but as a step closer to what it can become.

This is something we always forget with emerging artists. When you see all these kids at auctions, you wonder, who would want to re-sell a work that’s been done just six months ago? It’s just one step in the artist’s development. You think of Agnes Martin or Richard Diebenkorn—they became famous for a series of work late in life, when they were like 50. You can’t really treat the work of a young artist like “this is it,” and we have a tendency to do this.

Installation view of the gallery's current show, Baptiste Caccia, "Veduta," through May 21, 2016. © Isabelle Arthuis, courtesy of the artist and Super Dakota, Brussels

Installation view of the gallery's current show, Baptiste Caccia, "Veduta," through May 21, 2016. © Isabelle Arthuis, courtesy of the artist and Super Dakota, Brussels

That’s a good point. Going back to the history of the gallery, how did you get from Paris to Brussels? Why did you choose this city?

There were a few reasons. I didn’t want to be in Paris, because I lived in England and Australia for a while and although I love Paris, and being with my family and friends, I like coming back to Paris and not staying there for too long. So that was one thing, and of course Brussels was close by so it was easy to live there because you’re close to Paris, London, Amsterdam, Cologne, or Berlin is like a two-hour flight away.

So it’s convenient, and it’s still affordable. We have a big space compared to younger galleries in Paris, and I wanted a space where artists could actually have enough space to express themselves and to be comprehensive for the viewer. I came one day and visited the art fair, Art Brussels, and I thought it was a very interesting fair because it was pushing discoveries and I really liked the other galleries. In my opinion Brussels has the highest-quality rate of galleries. It’s a small city, but with a large number of great galleries and programs here—some of them are really amazing. For a city that size, it was very encouraging. And I wanted to be part of this ecosystem.

What are some of the galleries that really inspire you, in Brussels or elsewhere?

In Brussels, Xavier Hufkens has a great program, and among younger galleries, Clearing, Alain Levy, and dependance. More internationally, I’ve always been a big fan of Yvon Lambert, before he closed. I also love Spruth Magers, in Berlin, London, and now L.A.. I like Marian Goodman—I think she has probably one of the best careers that you can have. Paula Cooper, as well—she’s a great woman with a great program.

Brussels is also famous for its strong collector network. Is that something that helped to lure you there?

Not really, to be honest. I knew they had collectors, but it’s still a very small country. People forget that—they think Brussels is the El Dorado, that it’s the place to be, and you see a lot of galleries coming here to open and at first they say, “This is fantastic.” But I’ve spoken with some of them and they’re like, “Actually, it’s very tough here.” And I’m like, “What did you expect? It’s a tiny country.” There are something like 11 million people living here. That’s about the size of Paris.

People also forget that these collectors have relationships already, with galleries that have been here for years and years and years. If you want to claim your part of the cake, it takes time. It’s no different than anywhere else—to gain the trust of collectors will take you years. In our first year, we barely sold pieces to anyone in Belgium. We were selling to the U.S. and France and the U.K., mostly. Now, slowly, those famous Belgian collectors are coming here. We’ve started to get closer to the Flemish community, and have some good collectors following us. But we’re still selling a lot more outside Belgium than inside, at the moment.

How do you cultivate that foreign business? Is is mostly through fairs, or people purchasing from images (on Instagram, in at least one case, as a Bloomberg article mentioned?)

It’s mostly people who are familiar with the program—I’ve got good ties in London and Paris and New York, and we do a lot of business through mail and calls. We don’t do many fairs—I have been selective, and I’m trying to take my time, not just rush into doing many fairs.

Our first year, we did the fairs in Rotterdam, Brussels, and Paris. Next year we’re going to extend to new fairs we haven’t applied to yet, and try to get to the U.S.—I think it’s time. We have a lot of clients in the U.S., and they’re asking, “So when are you coming to New York?” But of course a fair in the U.S.. is another price from a European one, so we’re trying to be cautious and think about it and not go crazy.

You see so many young galleries opening and three years later they’re at LISTE, and you never see them again. They close their doors because they burn the cash too fast. For us, since we’re working mostly with younger artists, our average price is around 10 grand. If a booth costs more than 10 grand, you need to sell a lot of pieces to cover your costs and it gets very tricky. As a small business, you need to be patient and not rush. It’s a fine balance, to be at fairs to develop business but to be cautious because if you fail at two or three art fairs in a row, then you’re in trouble financially and you have no more cash to develop your artists and set up new shows.

Your roster is a really interesting mix—you have a lot of emerging painters but you also have artists like Jan Groover, this wonderful and underappreciated figure in postwar photography. How do you see your artists fitting together?

The program of Super Dakota is in constant motion. It’s a work in progress still, and probably it will always be a work in progress. I think I have a vision of what I want the program to become, and I’m slowly trying to get there with new artists. I have always wanted to have a synergy of works and ages—having emerging mixed with more established artists. I think creating a dialogue between younger and more established artists is very important to give a context to the younger artists, but also to create the dynamic for the elder one.

For example, we work with Joachim Bandau, a minimalist artist from Germany who is 80 years old. I know that he loves showing with our younger artists—he was a teacher for years, and he is eager to continue a dialogue with the later generations. This is what I find very inspiring, this kind of dialogue and communication. It’s nurturing.

This is also why Jan Groover is part of our program, because she’s one of the most important photographers probably since the ‘70s. I stumbled upon her work quite randomly, with a curator friend who was putting up a show. Photography has never been my thing, and editions are a nightmare to keep track of, but I found this work and I fell in love with it straightaway. It was beautiful and poetic, and formalist, something I quite like. I was shocked that actually no one was interested in her work at the time. I ended up working with her late husband, and now we’re preparing shows and there are new museum shows coming. We’re trying to bring her back to life. It’s an interesting challenge.

Although the work you espouse is in dialogue with modernism and other past movements, as you say, you’ve also ventured into Post-Internet art, with a show of GIFs.

Yes, we did a GIF show last year. That’s something I was very interested in for a long time. I saw artists using the format and I wanted to engage in a conversation about how to collect this media art. We offered the work on tablets, and I wanted people to be able to actually buy something and go home with it and hang it like another object. With Post-Internet art—I don’t like this term, but let’s use it—collectors typically get a USB stick or a hard drive, but I wanted to give them something that was easy for people to buy and enjoy at home.

Now we’re going even further by launching a film and video program—we’re curating a selection of film and new media work that we’ll be presenting in a dedicated space of the gallery every other month. This is something I’m quite interested in.

What do you look for, when you’re considering artists?

I’m looking for honesty, first. This is something that’s very important to me when I’m talking with new artists I want to represent. I want people who are engaging in a conversation with the history of art. I want people who are grounded in art history, who continue to push it further. This is something that’s very important to me. I want artists who have many layers—I really don’t like artists who are one-trick ponies, who find something and do it over and over.

Also, I’m trying to challenge myself with things that I don’t understand at first, that I’m not familiar with. I like that, because that’s how I know I can actually do something for the artist. If I know it by heart and really understand it, then I have nothing to say about it. But when it’s something that challenges me, I feel implicated and I really need to work for it.

The interior of the Atelier Brancusi, reconstructed by Renzo Piano, 1997. © Adagp, Paris. Image courtesy centrepompidou.fr

The interior of the Atelier Brancusi, reconstructed by Renzo Piano, 1997. © Adagp, Paris. Image courtesy centrepompidou.fr

Speaking of art history, I was looking at the gallery’s Instagram and saw that you will often post older works from your museum trips and excursions to venues like the Atelier Brancusi in Paris.

The Brancusi Atelier is probably one of the best places in Paris—it’s like a little heaven. It’s free, it’s very soothing, and you can imagine him working there. Brancusi is probably my favorite sculptor ever.

It’s all about context. As I said, I want the artists I work with to be grounded in the history of art and to continue a dialogue. When I find something I’m very interested in, even though it’s not a piece of art or an artist from the gallery, I feel it’s important to share it and then it gives context to what we’re trying to do and to the program. I’m trying to get people to understand Super Dakota a bit better, so sometimes I give them glances of things that inspired the birth of the gallery.

Who are your other artist-heroes?

Agnes Martin is my homegirl—I’m a groupie. My first art crush was on Caravaggio, then Mark Rothko. I love Franz Kline. I always thought that he was underrated—I feel like he has done the most beautiful Abstract Expressionist painting, which I find even better than de Kooning’s.

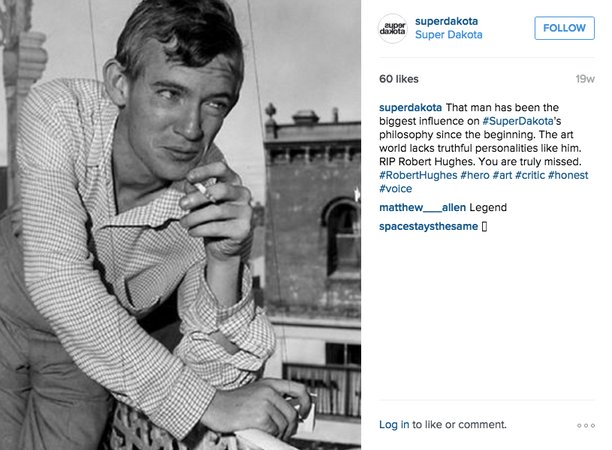

You also posted a picture of the critic Robert Hughes, and credited him as part of the inspiration for the gallery.

He’s another one of my heroes. I like his attitude—I like that he’s unmerciful. He’s probably the most honest person—he’s true to himself and what he believes, and he will not compromise.

That’s something I always try to follow. I don’t want to ever compromise when it comes to what we’re doing here. I want to be very honest. People will tell you about me that if I don’t like what you’re doing, I can come across quite harshly sometimes. But I don’t want mediocrity. And I think Robert Hughes was this kind of shepherd. He’s telling it like it is—he’s not going to sugarcoat it for you.

It’s what we’re missing in the art world. There’s no counter-voice anymore—how many critics are really pushing the art world further and keeping it on its toes? I don’t mind people being critical about what we do here, as well. If all we have is people patting us on the back, we’re not going to get better. I’m the owner of a very young gallery and I really listen to the critics, because I want to become the best gallery in the world. Of course we’re not there yet, our artists are still developing, and I want people to be honest about what we’re doing.

An image and appreciation of the critic Robert Hughes, from the gallery's Instagram (@superdakota)

An image and appreciation of the critic Robert Hughes, from the gallery's Instagram (@superdakota)

Are there contemporary critics that you read and admire? In Brussels or elsewhere?

No, not really, to be honest. There are from time to time some people that I appreciate for their sudden brightness of honesty, but I haven’t found a consistent voice that will fill the void.

Lately, you never get any criticism—if you want a review, you just have to pay for an ad in a magazine and you will get it. The system is crooked. You don’t get the freedom of speech that people like Robert Hughes used to have, and you don’t get to be kept on your toes and try to get better.

I understand that for a magazine, in the time of the internet, it’s very hard to survive. That being said, trying to keep a magazine meaningful means that you need to be very honest, and maybe not be so nice to the gallery paying for the advertisement. We need to find new models for magazines to exist.

What’s next for the gallery?

We’re at a stage where I want to grow the gallery, to get more staff involved and develop our artists in an international context. We’re reaching our third anniversary in September. Everybody says, “If you get to the third year, you’ve survived the worst.” I’m going to be very cautious—I’m like, “Let’s see what’s coming up.” Some of our artists are now reaching their second and third solo shows, and this is a critical time for us, to make sure that every show we do with our artists is a step further in their development, and people will trust that we have advised them rightfully.

I see all these galleries trying to open a lot of different places, this rush to have one place in London and one in Paris, one in New York, one in L.A.. In the end, it feels like a rat race. I don’t feel like my goal will be to have 10 galleries. I’d rather have a meaningful place, with great relationships with artists and collaboration with great galleries around the world. And I’d love to have a publishing house—I’d rather have that than a second space. We’re slowly getting into it, and this is something I want to develop.

What do you think is next for Brussels?

This is a million-dollar question. Every week I hear a rumor of a new gallery moving in. I assume that after the fair we’ll have a clear vision of what lies ahead for the city. I’m going to be honest with you—as I said, Brussels is very small. Belgium is very small. There’s only so many galleries that could actually live here, and there’s only so many collectors here. It’s not like it’s exponential. Already we’re reached a capacity—if you invite people to events, there’s always other things going on.

One good thing about Belgium, and Brussels, is that it’s quite laid-back. It won’t ever be New York, or London, or Paris. It will never be that exciting, this kind of electrifying city. It’s a very slow and steady pace. We might even see all this excitement coming down at some point, because most of it comes from abroad. The New York Times wrote this article about it, like, “Brussels is the next big thing.” It’s always been a great thing; it’s just that now they’re discovering it. So maybe the hype will slow a little.

That’s not such a bad thing.

No, it’s not. Working with a gallery, most of the time it’s a long run—it’s not a fast race. When you think about emerging art, we’ve been forgetting about this. People are trying to rush into it, to rush the artists, rush the market. It’s healthier to take your time.

Finally, I have to ask, where does the gallery’s name come from?

That’s another million-dollar question. It’s something I get asked a lot, and my answer is always that it involves a midget and a hooker! There’s no real story behind it. It’s a stupid name, but it’s a good little stupid name—it works really well. To me, it just embodies what I want to do here. I can’t really explain why, but it does.