In China during the early 2000s, new opportunities were opening up for artists. As the international art market began finding it's way to the mainland, some artists felt pressure to conform to market demands, did, and then reaped the financial benefits. Others, however, continued working on the fringes to pursue their anti-authoritarian art, and were left to their own devices to find support for their work. But luckily, these counter-cultural artists had the benefit of a relatively new phenomenon: the internet. According to director of the Noguchi Museum, Brett Littman, who has co-curated (with Zhou Yi) a presentation at this weekend's Outsider Art Fair, what emerged was arguably one of the first honest and authentic artistic movements that expressed the subjectivities of young people in contemporary China. The medium? Comic books.

Often appropriating the aesthetics typical of Japanese or Korean manga or anime, a group of Chinese artists injected their own narratives that were hyper-specific to the experience of living in a communist country, under surveillance and subject to censorship. Unable to sell or show their works publicly for fear of punishment by the government, these artists formed tightly bonded communities online. Ironically enough, Littman didn't find out about this thriving Chinese subculture on the web. Instead, he became acquainted the old fashion, pre-internet way: through studio visits, face-to-face interactions, and word of mouth while visiting Beijing. Just in time for the Outsider Art Fair, which opens today at the Metropolitan Pavilion in New York and runs until this Sunday, January 20, we speak to Littman about not only what we should expect to see at his fair presentation, but also about his fascinating journey into the underground comic scene in Beijing, where being anti-authoritarian means living a dangerously "normal" life.

You're showing ten Chinese comic artists at the Outsider Art Fair this week. These artists haven't had much, if any, exposure on U.S. soil. How did you first find out about them?

Two years ago (when I was the director of The Drawing Center ) I was invited to Beijing by a curator named Zhou Yi who had put on a drawing show and wanted me to come give some lectures. It was my first time in China, and I came with a feeling about contemporary Chinese art, which to be frank, was fairly dim. But my trip to Beijing was eye opening. Yi took me to visit some underground comic book artists that he had known over the years, which were incredibly fascinating. The two visits that I made—with an artist named Yan Cong and another artist named Wen Ling—were super crazy.

For instance, their comic books would be totally illegal to sell in any kind of bookstore or through any normal distribution channels. So, in order to buy the comic books I had to go to their studios. In the case of Wen Ling, he had all of his comics on his zip drive so he had to plug it into his computer and then print out the comics for me—because, of course, he's concerned that if his computer were taken, he'd be arrested. His comics tend to be pretty puerile, pretty sexual, pretty anticommunist in their approach. I felt like this was one of the first times I saw a contemporary read by young people on Chinese life in China. So those visits were pretty profound.

Then I had visited a gallerist in the 789 district, which is the arts district in Beijing; her gallery is called Tabla Rasa. She's been working with self-taught Chinese artists for a while, and has also been working with some of these comic artists. When I met with her she showed me quite a few books: both that she had produced and other compendiums of comics, including SC , or Special Comics , which a lot of these artists participated in the 2000s. I was super intrigued by what I saw.

I came back to The Drawing Center; I thought a lot about those comics. I actually thought about trying to put on a little show because I purchased some as I was going around and I ended up with a little collection. But when I asked Yi if he thought we could show them, he was concerned. The artists were concerned too. They didn't really want the work out there because it might have caused problems for them. So, I didn't pursue that as a show for The Drawing Center.

But for whatever reason, the temperature in China seems to have changed since then. I'm not exactly sure why, but these artists are becoming more open to the idea of international exhibition. When the Outsider Art Fair approached me to do a special booth, I felt the fair would be a really great opportunity to bring this work to the fore. It's work that no one has ever seen in the U.S. It is totally underground. The comics are amazing; very different. They're coming from the tradition of Japanese and Korean manga and anime, but the context and the content are very Chinese.

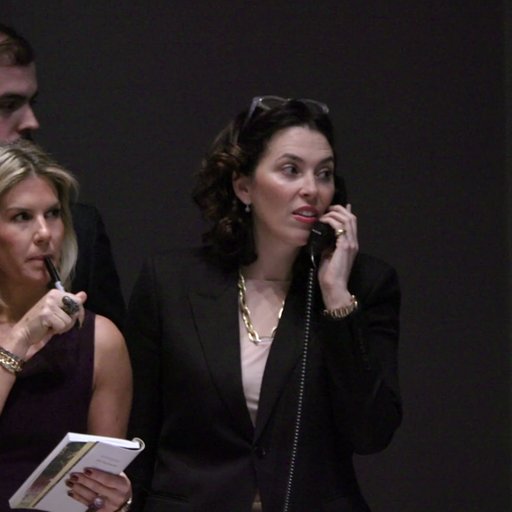

Xiang Yata, page from

Shoot the Night

(2011)

Xiang Yata, page from

Shoot the Night

(2011)

Are the artists you're showing self-taught?

Not all of these artists are self-taught; some went to college, to art school. But the systems of distribution in the 2000s were mostly on online graffiti boards and chat rooms where these artists would share their comics without actually selling them or printing them. Then later there was a group that formed and made some exhibitions, and then Special Comics came around in 2003 or 2004. And so there was a kind of moment about 15-16 years ago where there was a consolidation of this movement and it definitely gained some notoriety in China but it still remains very, very, very far underground.

Because of the online chat rooms, there's a very strong relationship between these artists. They form their own communities. There are some artists who sell things on WeChat, which of course is the equivalent of iMessage or whatever. On WeChat, though, you can actually pay for things. So there is a distribution system but it's an alternative distribution system. It's not like you can walk into an alternative book store in China and buy these things. But people are collecting them. Artists are selling things by message. People are going to these artist's studios. I can't say they're making enough money to live on just doing this; a lot of them have second jobs or do other things. But there's a deep, deep, deep passion and a deep community of people—probably now hundreds of artists that are making these self-published comics that exist all over China, and they're extremely supportive of one another. And there have been exhibitions so I don't want to say there haven’t... but only in China.

But what I was particularly fascinated about was the fact that in order to make a collection of these books, we had to go to studios and in many cases I had to have things printed out for me and then stapled. So it was very much like going back to poetry chapbooks or the zine world that of came out of in the ‘80s when I was in school. It felt very punk rock [laughs]. You really had to know someone who knew someone to get to someone. And then you'd go there and you'd have to have money in your pocket to be able to pay for it in cash and walk away with it. I found it to be very authentic. And again, many of these comics are quite critical of the Chinese government, and they can be quite sexual—either homosexual or semi-pornographic. These are things we just don't think of as things that can come out of China.

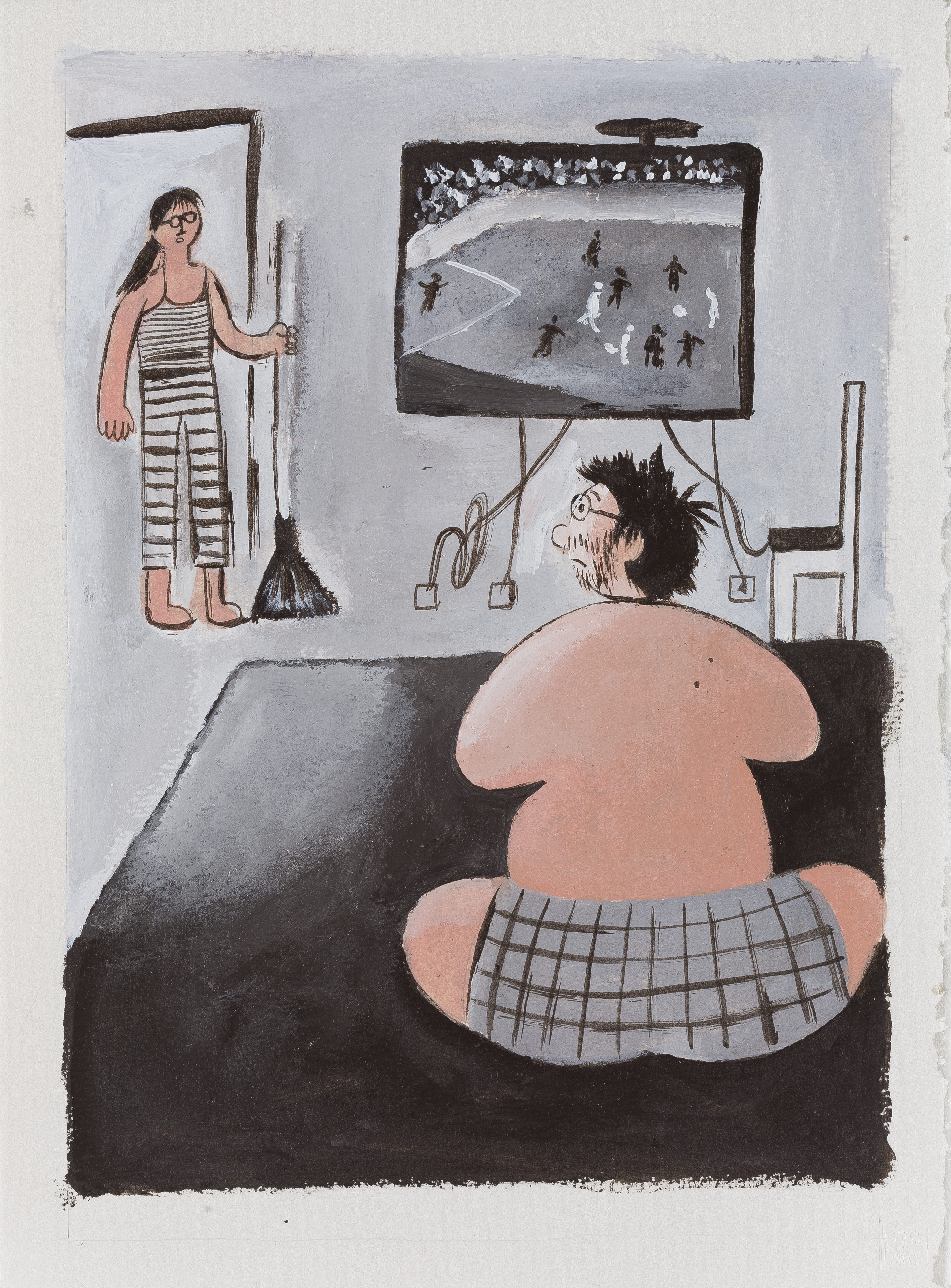

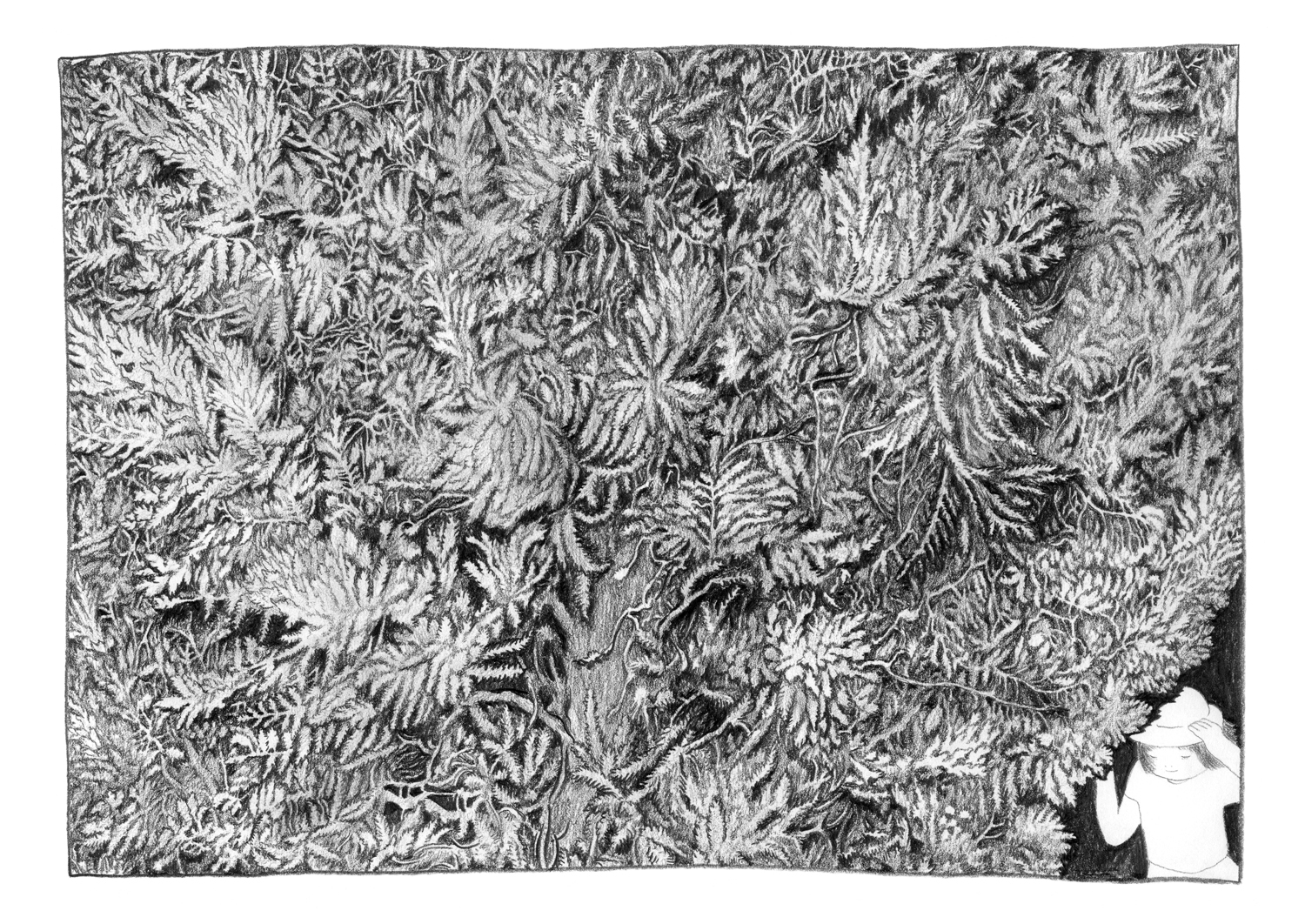

Yan Cong.

I Don't Want to Do Anything

, (2016).

Yan Cong.

I Don't Want to Do Anything

, (2016).

Can you elaborate on the specifics of this subject matter? What are some of the narratives that are coming out of this scene?

Yan Cong is probably the most accomplished of all of the artists we're showing. He has a publication called Narrative Addiction , which is self-referential. He is a sullen artist-type. (He describes himself that way.) A lot of his comics are infantilizing, to be honest, about sex or about watching television, for instance. In a lot of them he's in his underwear and he was quite overweight at some point. It has a R. Crumb-type feeling to it; very dark. A lot of it is also about repression in China and documents his interactions with police or his professors, who really hated that he was doing comic books. So a lot of it is anti-authoritarian.

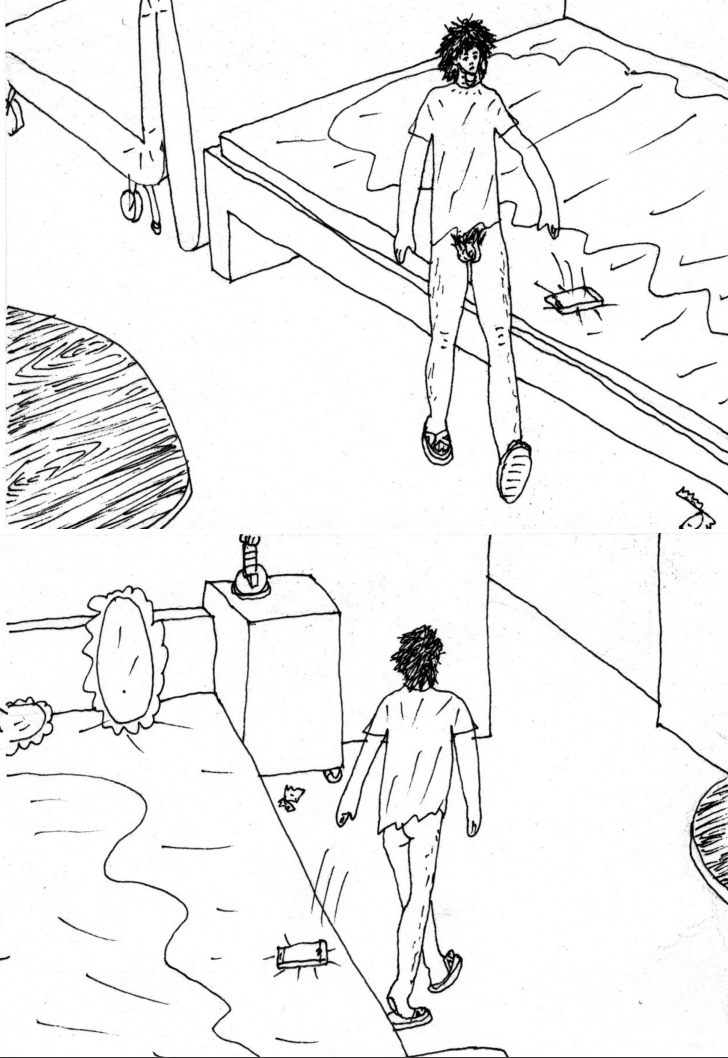

Also, Wen Ling has a little comic about some instance with the police at a 7-Eleven. The character ends up getting arrested because he doesn't have the right identity cards with him. In China, for many years people from the provinces were able to move into the cities, but now you have to have an identity card. In Beijing they looked the other way for many years because they needed workers. But now, there seems to be a crackdown and they're sending people back to the rural areas. So, if you don't have the proper identification you could be arrested and basically expelled from the city. These are realities on the ground in China, which we hear about and of course we know that human rights are an issue there. But I think these young comic book artists are really looking at those kinds of issues and putting them into narrative form in a contemporary way.

Wen Ling, page from

One Day in My Life

(2016)

Wen Ling, page from

One Day in My Life

(2016)

It sounds like the approach you're describing is very subtle. It's not like these are overtly political or activist works. Instead, they're honest depictions of what we think of as "normal" life—watching television in your underwear. But what we understand as "normal life" is actually very transgressive in China—or at least visually representing it and showing it publicly is. It seems almost daringly banal, in a way.

I would agree. It is very diaristic. It’s straight-shooting without any propaganda. It's a clear-eyed view of what it means to live in China, without government propaganda interfering. A lot of the circumstances are quite banal. These are not fantasy stories. They simply show interactions between people, which show the deep complexity of living in a communist suppressive society. So I would say you're absolutely right. These are definitely not considered to be activist. I don't think they're trying to change anyone’s view. These artist’s aren't out protesting. These comics are not being used as activist material. However, just the fact that they exist is problematic for the artists.

What would happen if these artists did try to sell their comics in book stores in Beijing? I guess the problem is that book stores would refuse to carry them. But hypothetically, what would the repercussions be?

I don't know what the answer to that question is. But if someone got under the skin of the Communist party, it could become an issue. I imagine they could be arrested but that's pure speculation. I've asked Yi this question a couple of times. He's had some hassles in China over some more Visa-related issues. He's run a gallery in Beijing now for a couple of years and has shown some pretty crazy stuff that also seems quite transgressive, at least in my mind. So I think they just have to fly under the radar and not bother anyone.

This is very much a cottage industry. We're not talking about a lot of money exchanging hands. A lot of these comics are $10 or $15 or $3; they're inexpensive to buy. But I think what's interesting is that this kind of alternative community has been built there. And it's been thriving and active since 2002 and this is really the first time it will be shown in the U.S. We're showing ten artists. We bought a lot of their comics and we're also going to be selling the original drawings—so you could buy a complete comic book. Probably the biggest one is 21 pages, so you can actually buy the 21 original drawings for the comic.

This is very a general question but, why comics? Especially considering that a lot of these artists were trained in traditional media in art school. Out of all the mediums, do you think that the comic book was appealing to these artists because of the way that it can be distributed online?

Definitely. I think it was about immediacy. It was about sticking the middle finger to the scene of the professors and the people in art school who were probably asking them to copy Western paintings or to think about more traditional ways of working. I think that because this community coalesced so quickly, (and again it was about graffiti as well), it was an embrace of an alternative culture that I think really represented the feelings and attitudes of young people in the early 2000s as it was in response to the kind of art market that was beginning to boom in China. They took a different path: one that was about communication between peers. Yan talks a lot about how he was encouraged by his online peers. He was very depressed at art school, and what encouraged him was posting his drawings online and getting all these responses. There he felt like he had friends, people that were interested in what he was doing.

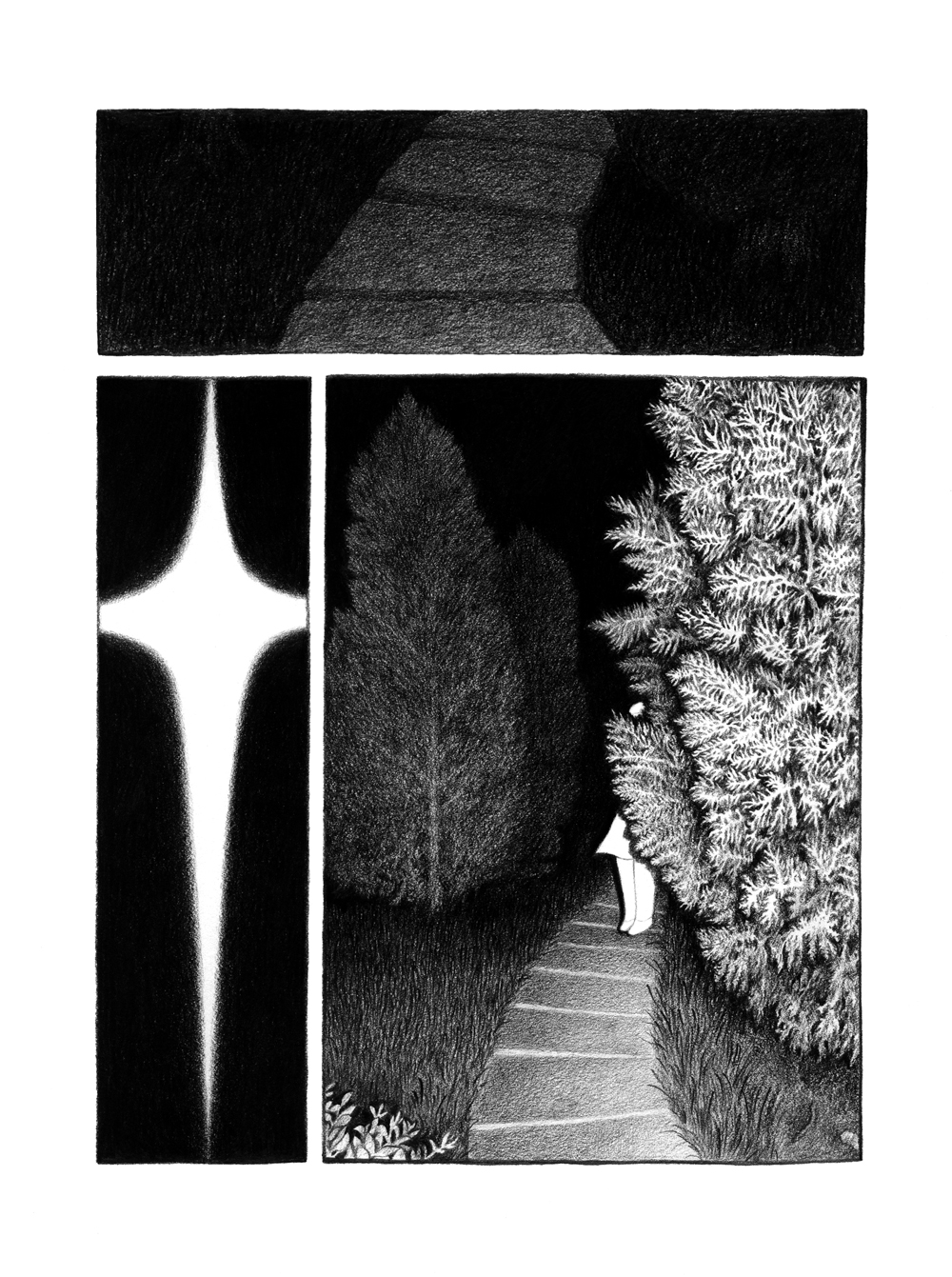

Xiang Yata, page from

Shoot the Night

(2011)

Xiang Yata, page from

Shoot the Night

(2011)

So these works are anti-authoritarian because they're pushing back and being critical of Chinese communism and censorship. But they're also anti-authoritarian in that they're simultaneously pushing against the cannon, against what their professors—and probably most people—think of as "fine art," which is certainly not comics. The fact that they're not using oil on canvas is a form of protest for them.

Yes, although in China, there really is no distinction between drawing and painting. A scroll or calligraphy is considered pretty equal to painting. (Of course in the Western world, painting has been considered at the top of the hierarchy with sculpture coming in second.) It was funny, I gave a lecture about drawing in China, and actually there's really no word for "drawing." There's no pre-sketching... I mean, you could sketch but they don't view that as a kind of preparatory drawing. If you draw, it's making marks, it's the same thing as painting because there are master ink brush painters—so it's not about the medium or the substrate. A work on paper could be just as equal or even more important as a work on canvas or a work on silk, so they don't make those kind of distinctions. Which, of course, made my lecture incredibly complicated, because every time I said the word "drawing" it required a ten-minute explanation [laughs].

Speaking of getting lost in translation, do you feel that viewers at the Outsider Art Fair who can't read Chinese are going to be able to understand the narratives?

Yes, I do. They're just like graphic novels and are relatively easy to understand visually. If you're interested in Zap Comix, or R. Crumb, or the American scene of alternative comics, or in manga or anime from Japan or Korea, if you're interested in (as you were calling it) the quotidian day-to-day life in China as represented by young people, you'd definitely be interested in this exhibition. Unfortunately we can't translate all the text in the comics but Yi will be in the booth and be able to translate on the fly if someone would really like to know more of the details. But I believe the original drawings and the comics themselves will resonate with the crowd that comes to the Outsider Art Fair.

What's the price range of the works you're offering?

The single drawings could range from $300 to $3,500 for a complete comic book. The comic books that we brought will range in price from about $15 to $150 for the Special Comics that we were able to purchase, which are actually very rare right now in China; they're all sold out. We were able to purchase about four of those books and they're about 500 pages. So that's the compendium that we have that gives a good overview.

Looking forward to seeing the show!

See you there.

RELATED ARTICLES: