According to CNN, if the American prison population were its own city, it would be the fifth largest city in America, with a population larger than Phoenix or Philadelphia. In the U.S. there are almost 2.3 million people behind bars—more than any other country in the world throughout history.

Clearly, mass incarceration in the U.S. is out of control. It’s become so catastrophic that even President Trump supports reform; he’s publically backed the First Step Act. This bill, which the Senate passed on Tuesday night, will soften some federally mandatory minimum sentences, provide funding for rehabilitation and re-entry programs. While the bill only modestly tweaks the federal criminal justice system (not the state and local systems that largely account for America's prison problem), it's definitely a step in the right direction. Amusingly, Trump supports criminal-justice reform while his supporters continue to chant “lock her up” at rallies in regards to political opponents like Hillary Clinton, and recently, Dianne Feinstein.

Hopefully, the U.S. government never reaches a point where it actually locks up those that oppose its policy—like in China. In 2011, the Chinese government imprisoned artist and outspoken critic of the communist regime, Ai Weiwei , during a government crackdown that targeted dozens of bloggers, human rights lawyers, and writers. CLOG , an international publication that critically explores a single topic through numerous multi-faceted perspectives, interviewed Ai Weiwei back in 2014 for their issue CLOG: Prisons .

As we bask in the small victory of passing the First Step Act, we’ve excerpted CLOG’s interview with the artist about his time in prison. Here, Ai Weiwei opens up about his experience in prison, the relationship between imprisonment and surveillance, and the role of architecture in the prison industrial complex.

The 'Prisons' Issue of

CLOG

. Image via

CLOG

.

The 'Prisons' Issue of

CLOG

. Image via

CLOG

.

CLOG in conversation with Chinese artist/activist Ai Weiwei at his Beijing studio on February 26, 2014.

On April 3, 2011, you were arrested by police at the Beijing Capital International Airport and subsequently placed in detention for 81 days. Can you please describe this experience, and the space in which you were detained?

Oh, it would be a long talk. I can only really tell you the basic conditions. I was waiting in line to go through customs, and they stopped me and told me to go to another place to have a talk. They were wearing plain clothes, so I knew they were secret police. What I wasn’t prepared for was when they led me to a van, put a black hood over my head, and started to drive. In about two hours, we arrived. I could sense that we’d arrived somewhere because the car kept stopping, meaning there was a gate.

When the car started again, I knew that we had been checked by security, and then I was led upstairs by two guards, one on each side—because I could not see anything. The funny thing is they first moved me upstairs and then realized that the room was downstairs, so we came downstairs again. They told me to sit, and then they took off my blindfold…

After some time, I was blindfolded again and moved to a second location. When they took off my blindfold this time, I was in a room measuring 3.6 meters (11.8 feet) by 7.2 meters (23.6 feet). I could tell from the size of the floor tiles. It was a very simple bathroom, and the whole room was wrapped in soft cushion or soft white foam which was taped roughly on the wall, to secure the space to prevent you from killing yourself. Even the toilet was wrapped with soft materials. But it was a very clean room with nothing in there, only a white armchair for me to sit in. The entire chair was wrapped with soft materials, and my left hand was handcuffed to the armrest. There were two metal chairs for the interrogators to sit on. There was a small office table, and two soldiers stood in front of me about 80 centimeters (31 inches) away. They stared at me all the time, almost without ever blinking, emotionless. There was no window. I could tell whether it was day or night though, because there was a fan in the wall and I could see light through the hole of the fan. So that’s basically the conditions I were in.

There was no exercise outside of that room. I could ask for permission to have a walk inside the room on six floor tiles. Each tile was 60 centimeters (2 feet) by 60 centimeters, so walking, that was 3.60 meters (11.8 feet) by 60 centimeters. Basically, my daily activities were sitting, being interrogated, walking, taking showers, and sleeping.

The building, of course, was top secret, used by the state to detain so-called top criminals or enemies, people like me detained mainly for economic crimes and sensitive political cases. The security and the secrecy level was very high, but later through a very difficult process I managed to find the location on Google Maps. [Laughs]

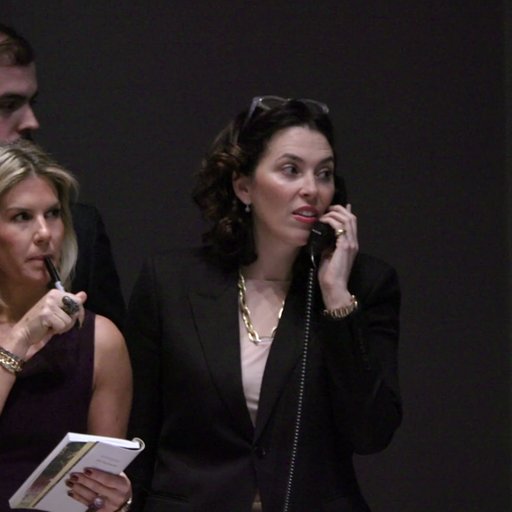

Ai Weiwei sitting in a replica of his prison cell. Image via Smithsonian Magazine.

Ai Weiwei sitting in a replica of his prison cell. Image via Smithsonian Magazine.

Where is it?

It’s in Beijing in a very public, populated location. Through the fan hole, I could hear women or children chatting and passing by, though I could not tell what they were saying. Based on these sounds, though, I realized that I wasn’t in a military base or jail. And I could tell that the building only had two levels based on the pipelines—there was no water system above the bathroom, meaning I was on the top floor with nobody above me.

What did it smell like?

The smells in the beginning scared me. When I moved in, I smelled a very strong chemical, like something used to clean up a body or blood. You smell that in the operation room in the old hospitals. That smell still remains a mystery, though it might have been because of the beatings... not me, but I found out later from the guards how they treat other prisoners. I don’t know if they were saying this to intimidate me, but they told me that the others are beaten, told to take off their clothes in front of an air conditioner turned to the lowest level, and are questioned in front of the cold air. You cannot hold on with that.

What did it sound like?

Just the fans, twenty-four hours a day. That started to create a not loud, but high-pitched sound, which eventually created a kind of illusion. Like, I could hear thousands of people singing together. And they never stopped singing, twenty-four hours a day. You start to have… hallucinations.

So they gave me pills. I had never seen pills like that so I would ask the doctor what they were. The doctors would say, “It’s to fix your nerves.” That was very suspicious. But the doctor came three times a day, and sometimes seven times a day. It felt a little bit like a laboratory.

Were the lights always on?

Always. Very low, sad lights. But on twenty-four hours a day. There were also three surveillance cameras, one on each corner of the room and another in the bathroom. They covered the entire room to make sure the guards could not talk to me. They’re soldiers, 20 years old, and they never left this building. They arrived on post secretly. Two or three years later, they’ll secretly transfer out to another poor province. So everything they do in Beijing is in this room. Every two hours when they change shifts and leave the room, two other guards search them outside the door, making sure they don’t bring out anything.

Did you ever see what was outside the door?

No, the purpose of this kind of detention is to cut off any sense of anything you understand or know or remember from the past. They’re really successful at that. The only sense of the outside came after they asked me if I wanted anything, and I said I needed coat hangers because I wanted to wash my underwear and socks, and I needed hangers to dry them. Otherwise you have to leave things on the back of the chair. So out of mercy, they brought me six blue plastic coat hangers; you know the cheap things you can find in the markets. Of course, the next day when the soldiers came in they all shook their heads, saying that this was impossible, that something like this could be brought into a jail cell.

When you were released, did they put the hood back on?

Yes, of course. They had to protect that compound. I still found out where it was though, and later on I told the police who detained me, “You know, I know where it is, where I was detained.” He asked where. I told him the address. He was shocked. He said, “I never heard about this. Don’t tell me that.” I went back there once and took some photos outside the door. It looks normal, like nothing special.

Image via The Daily Beast.

Image via The Daily Beast.

How did it feel when you left such a controlled environment and reentered the world?

It’s like coming out of a satellite. After being released, they first brought me to a normal police station. I said I wanted to go to the bathroom. They took me to the bathroom, and I saw my image in the mirror for the first time. That really shocked me… the most shocking image I can remember is seeing myself in the mirror.

We’re accustomed to inhabiting spaces where there is almost always some surface material that allows you to see yourself...

If there had been a mirror in my cell it would have been a very different experience. Being able to see any kind of reflection—even a distorted image—would change your whole perspective.

How did this experience impact your thoughts on space and architecture?

I now think there’s no space or architecture really designed for inmates. Rather, places like where I was detained are designed for control. When you’re a prisoner, your sense of existence is completely destroyed. Prisons are often designed not as a shelter to protect the law or to provide security, but rather to make the humanity of the prisoner disappear. They do not consider the very basic needs of a human being. It’s overwhelmingly powerful. Prisons make sure you understand the treatment of space as a punishment. This is an insult to all humanity.

Is it therefore morally wrong, in your opinion, for an architect to design a prison?

I don’t think so. I think architects should design anything. There’s no “morally wrong” or “not wrong,” but just how well you design. Space is a huge part of any society, and someone has to design it. And whoever designs it is an architect.

So who do you hold responsible for the environment in which you were detained for 81 days?

It reflects the whole society. There’s a very clear definition of what a prisoner is. You’re being controlled, and you’re vulnerable. You’re being watched. Your activities are being carefully monitored, and they can get to you at any time. This situation can be experienced in a small physical space like a cell or in a much larger environment as a so-called free person. Why, we have two buildings next to us right now, built just for watching us at all times.

Right here, surrounding your studio?

Yes. And there are twenty cameras around our yard. And the phone is tapped. The computer is checked. This is a kind of soft detention.

When I walk in the park I see secret police behind books, bushes, taking photos. If I go to the restaurant they check every table. The whole society is about control, about how much they know and how fast they can get to you.

The picture that [Edward] Snowden revealed is scary. It shows that even a democratic society like the United States still has no trust in its own people, and it keeps secrets files on people. It brings into question the so-called civilized world. This is morally wrong.

So we’re in this beautiful space and you have your home, your work, your garden, your collaborators, your cats… do you feel that you’re living in a prison?

Actually, when I built this house, my mom visited, and the first thing she said was that it was like a prison. [Laughs] You know, people’s ideas about space are so different. I think what made her compare this to a prison was its isolation from the neighborhood and the style. This is interesting. Living in a prison is not about the walls, the bars, the windows, or the security guards, but rather how closely you are being watched by authority. When you’re being stared at by a vicious animal, it scares you, because they keep staring. And you know, they do that because they want to have the next move. [Laughs]. We all accept that we are being carefully watched here.

Image of Ai Weiwei's studio in Beijing, China (2014). Image via CLOG.

Image of Ai Weiwei's studio in Beijing, China (2014). Image via CLOG.

You mentioned two buildings built by the authorities adjacent to this property.

Yes, in front of this building. Regulations do not allow four-story-high buildings in this area, but they built a four story building. This is how I know it was built by the authorities. They wanted to look down into our garden. Actually, this is a game every powerful state plays. Even the United States plays it, like at Watergate during Nixon’s time or even today, with the U.S. being accused of listening to the German Chancellor’s conversations. It’s like a card game, but they know what cards you have in your hand. I think this kind of cheating is unspeakable. China does it in the most obvious way, but I’m sure all authorities do it. They think they’re more powerful than you. In fact, there should not be any higher power than the individual. In reality, it’s very different.

Are there ways you escape your current soft detention—if not literally then psychological—such as when you listened to the sounds of the women and children through the wall fan during your detention?

Yes. So long as you maintain some connection to reality, this type of detention doesn’t really work. If I see a cat passing by, if I can look at that door and know that it will open when I turn the handle… these things destroy the state’s psychological control. Sometimes I remember what Wittgenstein said: “A man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that's unlocked and opens inwards; as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push.” Soft detention requires your participation. For example, you always have to remind people you’re being watched. When people call me on the phone, the first sentence I will say is, “this phone is being tapped.” I’m afraid because if they don’t know, they can get in trouble when they say something privately to me. Soon, you realize very few people will call you. For me, it’s fine, but you can see in this case soft detention really works well.

But maybe that camera in front of my door is never even turned on. One time, a big truck hit the camera, and the camera turned to another angle. For a month, nobody came to fix it. If somebody had been watching on the other end, it would have been fixed the next day. In the 1990s, China used to put sculptures of policemen standing next to highways and streets. They scared most drivers, who didn’t know they were sculptures. Propaganda works. Brainwashing works. Intimidation works.

How do you intend to address through your future work the issues discussed today?

It is very difficult to work in a society like China’s. Basically my work is not exposed to the public here. Most of my work is seen in the West today. My name cannot even appear on the Internet in China. They will simply delete it. At the same time, the state is so powerful, but is scared of an individual like me, who only tries to free himself.

For the upcoming exhibition on Alcatraz in San Francisco, we have been focusing on the experience of different kinds of political prisoners around the world, people who have been put away only because they have an opinion, or because they peacefully exercised their rights or expressed themselves. Can a society afford to silence those people who have different ideas? This is a disaster for society, and it needs to be consciously and publicly discussed.

I have no clear political intentions, only the exercise of my essential rights. But of course, I protect those rights through public expression, by sharing information, by letting people know how this world looks like or at least how my reality is. This is a very important task for me. It is my job. I have to do it. It is my duty. And I have to consider myself one of the lucky ones. So many people—writers, poets, journalists—have been put behind bars simply because they freely exercised their rights or expressed their concerns.

Do you have any idea whether or not these other people have had experiences similar to yours?

My experience is unique because the authorities somehow see me as some kind of very dangerous person. Others are treated as normal criminals. The police will have two dozen people sleeping in one big bed, so you cannot even turn. There’s also a lot of “self-punishment” in these normal cells. There are hierarchies inside, involving who is the boss and who is the newcomer. You can always be physically or psychologically abused. It’s a little dark society.

In the end, what is the role of architecture in relation to all of this?

I think of architects as very strange creatures. Architecture is only half intellectual and mostly just practical. There is only a small intellectual side to the profession, and it very rarely involves moral judgment. Sometimes architects think they are so powerful because they make something happen, like a god, but of course it’s always plagued by politics and money. It’s not so stable.

And how is art different?

Art can be very different. You don’t have to be in the commercial world. Many artists don’t sell a piece in their lifetime. But architects, you work for somebody to use it, you know?

One final question. Your father, the poet Ai Qing, was imprisoned in 1932 for opposing the Kuomintang in Shanghai…

Yes. Today I was reading early poetry he wrote in prison. He started writing poems at this time. The first day I was detained, I remember telling the police that it reminded me of my father. They told me that today it is different. Then later, I realized that yes, it is very different. My father still could write poetry in prison and send it out to be published. But today in China, you cannot. Even your family doesn’t know where you are. You have no lawyer. You have no way to send out anything, not even a toothpick.

RELATED ARTICLES:

"Make Tea Not War": Eight Examples of 21st-Century Protest Art

Ai <3 NY: A Guide to Ai WeiWei's NYC Takeover

Art Vs. Trump: 40 Creative Acts Of Resistance Since Inauguration Day