The stories we tell through public art shape the social landscape. They have the power to make some people feel at home, while making others feel unwelcome. And they reveal that history isn't a single, objective narrative; it's a series of subjective experiences that rely on a careful and considerate retelling—a responsibility often left untaken. Of course, this all came into razor-sharp focus when Americans debated, in very polarized and publicized ways, whether confederate monuments should or should not be kept in public space. The people in the city of New Orleans were no exception. Four confederate monuments, including an 80-foot-tall memorial of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, were removed in 2015—but not without years of protest from both sides of the issue.

Arts organization Paper Monuments stepped in during the aftermath to tell a a different kind of historic narrative within New Orleans' public space. Here, Artspace speaks with the director of the organization, Bryan Lee Jr., to discuss how the project works, and to unpack a few particular historic events in the city's history that are resurfacing in meaningful ways today. Plus, Lee Jr. describes how proceeds from the new Artspace x Maison de la Luz Edition by visual artist Swoon will benefit the project.

How did Paper Monuments begin?

Paper Monuments is a public art and publication project that started as a response to the growing call to remove confederate monuments and symbols of white supremacy across the country. There was a group of individuals in new Orleans who were actively in support of that movement called Take ‘Em Down NOLA. They pushed heavily to get the city to act, and when the city did act, the question became: What's next? How do we reconsider what monuments look like in this city moving forward? Ultimately Paper Monuments came about by asking those questions, not only of ourselves but also of the masses, of the public.

How is the public involved in creating monuments through your organization? What is the process like?

We have two ways of initiatiating monuments. The first phase is called Public Proposals; we ask every individual we can from across the entire city to submit a proposal that imagines a story that wraps around people, places, events, and movements throughout the history of the city—what's important to tell, what stories are important to lift up. So that's one process.

Then there is a second process for the academics, the historians, the story-tellers of the city. We ask the same set of questions, but then we partner them with artists to do a series of posters that reveal bits and parts of our history. The two processes together offer a methodology to get not only the public's opinion about what should be in public space, but also to publish a more academic version of history bound to contemporary art that allows stories to connect to a contemporary community.

Where do the Public Proposals submitted by community members live?

The proposals become a couple of things. We turn them into graphic submissions. When the proposals come in, we have an artist-in-residence that turns it into a visual. Those digital proposal posters are on our website. Then the data that comes from the proposals is gathered and used to create a collective narrative. We take every word from every single proposal—thousands of them—and transcribe everything, give them category tags, and then co-locate words. We have a computer script that runs through the data and determines what has been deemed important by the people of this city. That is being formulated for our final report, which will go out to the city sometime in February or March.

Can you point to a few particular Paper Monument posters that you feel encapsulate the project?

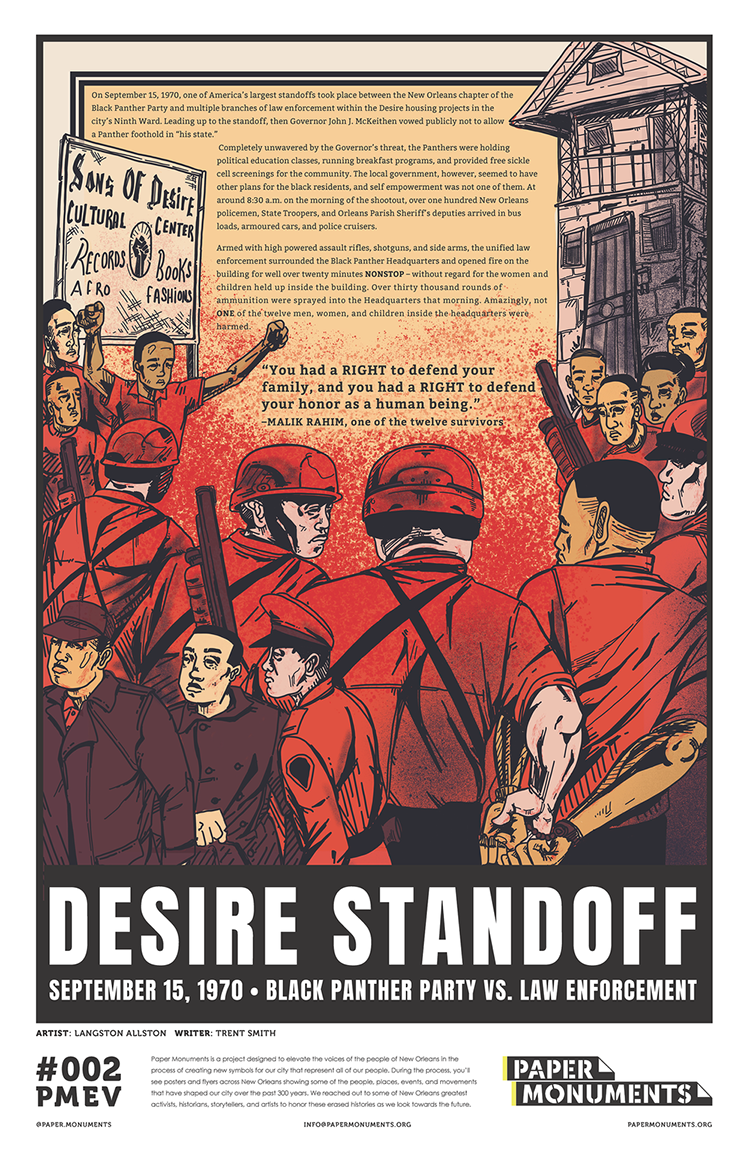

I think there are two in particular that are extremely important to this process, not just because they're good narratives but because they reveal something in our city that otherwise maybe wouldn't be understood. One is “Desire Standoff.” In 1970, the New Orleans city police raided a Black Panther house on Desire Street in the 9 th Ward. That house ended up getting demolished in the process. One of the young people who was there that day now works in the city. After seeing the poster, they’ve been essentially serving as a docent on the streets, telling the story in live action in front of the poster. That in itself is reveals the cycle of people living a shared history; that shared history is put into the public, and then the people involved are able to speak to it. There's something really powerful about that.

Artist: Langston Allston. Storyteller: Trent Smith. Image courtesy of Paper Monuments.

Artist: Langston Allston. Storyteller: Trent Smith. Image courtesy of Paper Monuments.

The other one is a “Dorothy Mae Taylor,” and it hits us in a similar way. Dorothy Mae Taylor helped to desegregate Mardi Gras in the ‘90s. It sounds ridiculous to say because the ‘90s aren’t so long ago, but that’s when it happened. The idea that an individual person like her can have such a tremendous impact is significant—but on top of that, her family found those posters and printed them onto t-shirts. Taylor’s family goes to city hall for various town meetings and city planning events and when they do, they wear the shirts with her face on it. It’s come full circle; her children watched their mother advocate for desegregation in this city, and are now able to represent her continually in their efforts. That is pretty powerful.

Another poster that stood out to me was the “Streetcar Protest 1867,” which describes an event that was initiated by a black man named William Nichols who boarded a white-designated streetcar. The act sparked days of protests by hundreds of people, and ultimately lead to the integration of New Orleans’ street cars (until Louisiana law mandated segregation in 1902.) This happened almost 88 years before Rosa Parks famously refused to sit at the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. That’s incredible. And I had no idea about this story until I came across it via Paper Monuments. There was so much work that was being done in New Orleans that I think got a little buried in terms of our national history. It seems that another crucial component to the project is that it’s elevated the courageous efforts of the people of New Orleans, who in many cases, helped paved the way for important progress in other parts of the country.

Absolutely. Plessy v. Ferguson happened around that time and lead the charge for other mobility-centered protests throughout the country. I think that's pretty important.

Where and how do people see these posters in the public? Do you target certain neighborhoods?

The actual posters are in bookstores and libraries across the city. We've been kind of ubiquitous about that. We also distribute them as newspapers, which we print and hand out. And we actually post them. We scale them up to larger than life, usually four-feet-by-eight-feet, and we wheat-paste them to buildings that are either demolished or going through some sort of construction. We use unoccupied buildings as canvases for stories. We generally put them up in places that are adjacent to transit lines. Transit lines, like the streetcar and buses, allow us to access people from other communities or neighborhoods who are walking around after they get off the bus.

View this post on Instagram

Obviously confederate monuments are controversial. Are Paper Monuments controversial? Do you get backlash or criticism from the folks who fought to keep symbols of white supremacy in New Orleans?

Yeah, I mean racists will always find racist ways to be racist. We do have pushback from people who are actively seeking to tarnish the project in various ways. Most of the criticism is about the historic stories we tell, and less about the proposals that community members submit. Those proposals are more about what is possible, what we imagine in our future.

What is the value, in your mind, of having a public understanding of the city's history?

We tend to isolate history into individual figures, into moments that have a winner and a loser. But our history writ large is obviously more complex than that. So the advantage of telling so many stories and listing the people, places, events and movements that shape those stories is that we can be complex; we can talk about the nuances of our stories in ways that allow us to see the connectedness of all of them. That is our purpose—to give space to tell enough stories to see the full picture. And right now the American instinct is to idolize individuals. And when those individuals come down for one reason or another because they don't reflect our national ideals, we then idealize the last person who died that fits the moment. What we try to do through this project is to hold to space for that not to happen; to hold space for the absence; to hold space for us to talk about what ideas pervade in our world before we try to seal them up. That's the importance here.

Artspace has partnered with Maison de la Luz to produce a limited edition print by visual artist Swoon. Proceeds support Paper Monuments. How will this charitable edition support the project?

Honestly, we are attempting to survive every day. The grand majority of the dollars that we pull in goes directly back out into the production of these stories. So whether that's through the poster printing or that's through mural making, it's about the production of the stories for the people. If we want to continue to do that, if we believe as a city that it’s important to maintain and tell those nuanced and complex stories, we need support.

Swoon,

Daniella

, 2005/2018 is available on Artspace for $500. The edition was produced in partnership with Maison de la Luz. Proceeds benefit Paper Monuments in New Orleans.

Swoon,

Daniella

, 2005/2018 is available on Artspace for $500. The edition was produced in partnership with Maison de la Luz. Proceeds benefit Paper Monuments in New Orleans.