French is Camille Henrot ’s mother tongue, though this hugely talented, Parisian-born artist, excels in teasing apart the nuance and contractions in the English language, and in contemporary life, via her videos, films, sculptures, paintings.

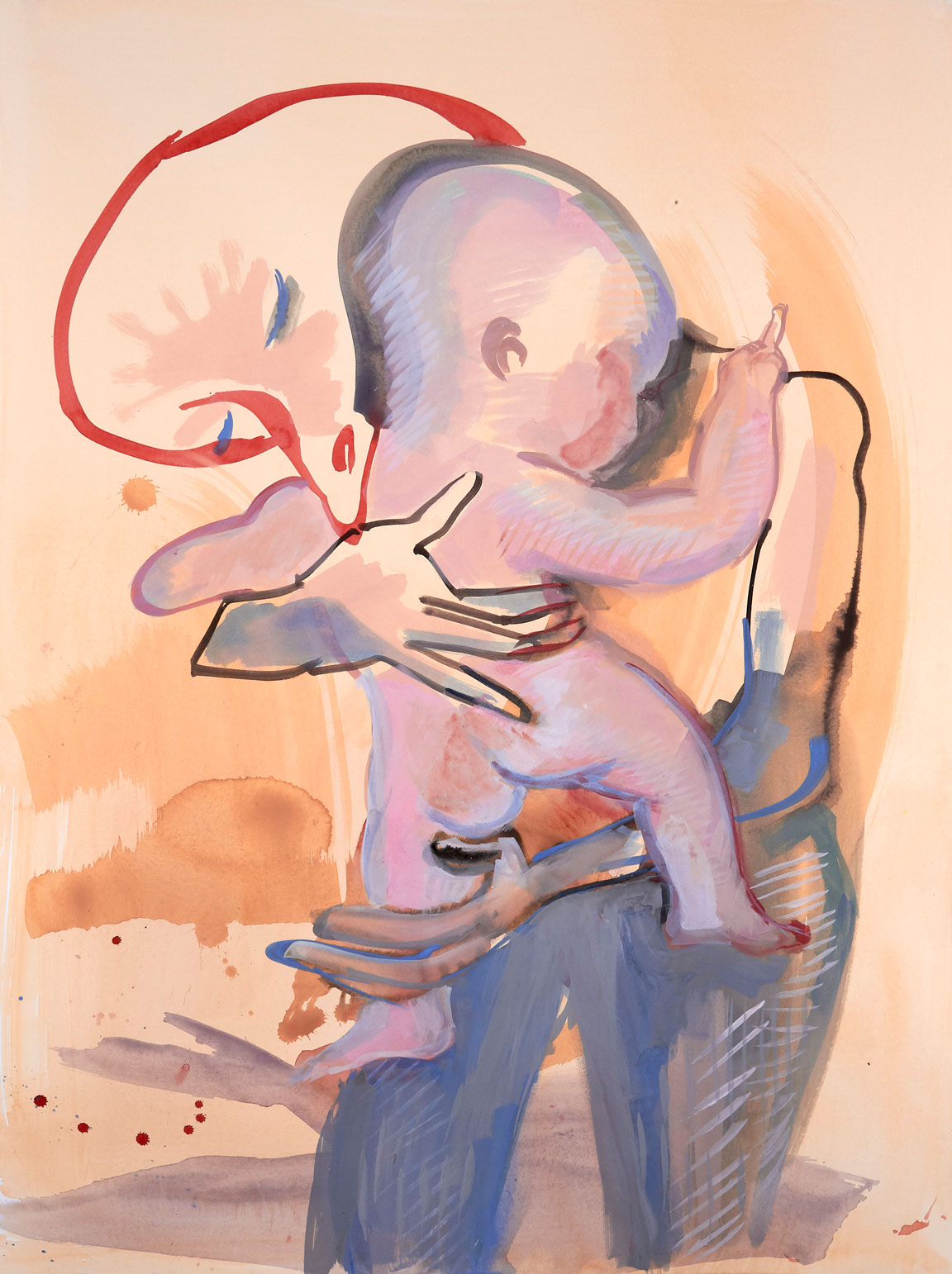

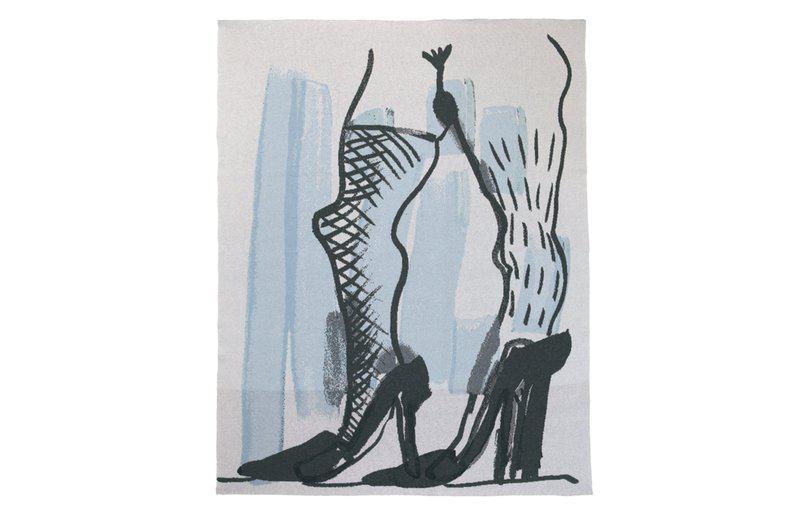

Her new Artspace edition in association with MOCA LA, entitled Mother Tongue , upsets the traditional motherhood tropes, in a terrifying, yet toothsome image.

Henrot's show Mother Tongue, featuring the work, opened at Kestnergesellschaft in Hanover, Germany , last month and runs through August.

In this interview, the artist resists the urge to embrace an entirely autobiographical reading of this work, but instead revels in the messiness of parenting, personal relationships and how our childhoods shape us as adults. As she says, “if you pull on these strings, everything comes together: sexuality, love, death, and much more.”

Read on to understand her work more deeply, as well as grasp her hopes for a post-pandemic world, and why drawing, for her, is a lot like going to the gym.

Camille Henrot - photo by Maria Fonti

Camille Henrot - photo by Maria Fonti

Where do editions fall into your practice? My mother was a printmaker and an engraver, so I attribute a lot of value and care to printmaking and editions in general. And I really enjoy both making them and collecting editions from other artists.

What would you like people to get from this edition? I certainly don’t want to give direction to people about what or how they should feel. I always try to leave things as open as possible. I like to think about the possible interpretations of my work in a geometrical sense – that the range of interpretation should be like a fan pointing to many directions and angles, rather than a narrow and limited cone. Sometimes the price I pay for that is misunderstanding but I much prefer to pay that price than to fall into a unidirectional representation.

What made you choose this particular image?

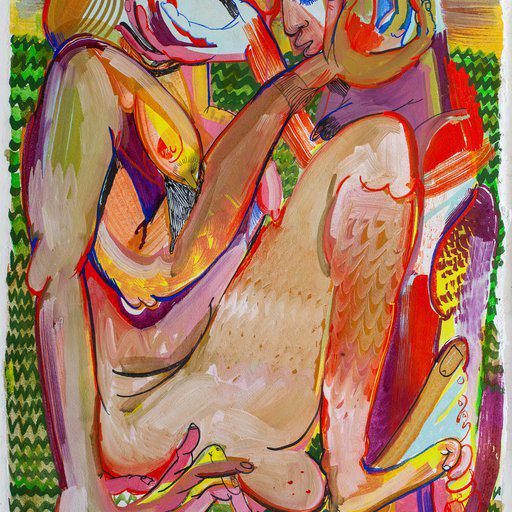

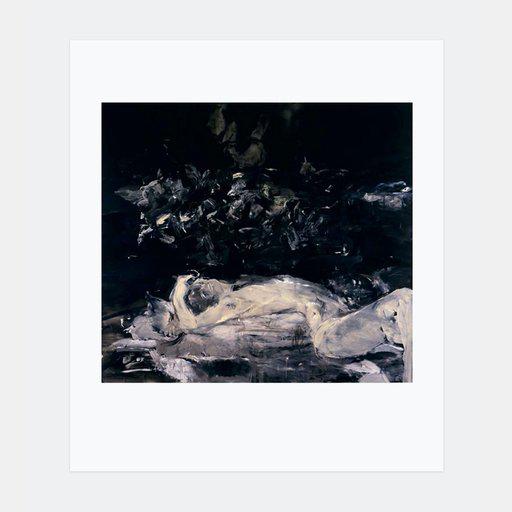

The artwork is part of a body of work called System of Attachment, which includes paintings, drawings and sculpture, and relates to early childhood development and the ways in which concepts of language, gender and sexuality evolve. The title of the series comes from psychology. There are two developmental systems: the system of attachment, and the system of exploration and both are complementary. One is necessary for the other to grow. Attachment and exploration are both early stages of childhood development but are also linked to the experiences of parenting.

The title suggests that the image can be read on a number of levels, doesn’t it?

Yes. One might think it’s a traditional representation of a mother embracing her child but it also looks like Cronus, devouring the child a little bit. It’s not very clear. It’s called Mother Tongue but the gender of the parent and the nature of the embrace are ambiguous. The arm that carries the child is weakened and exhausted, in contrast with the opulence and fleshiness of the body of the child.

You are a relatively new parent yourself, how has your personal experience inspired the work? The minute I willingly answer this question, I put my work at risk of being seen as purely anecdotal. Women’s biographies have traditional been used to qualify their work, whereas men’s experiences always have the potential to be universal. But how can early childhood, birth and motherhood be anecdotal when we are all, to borrow a phrase from Adrienne Rich, 'Of Woman Born'?

To me, parenting is a very interesting field or source for material because of its messiness. It’s complex and ambivalent and unstable. There is tenderness but there is also anger. There is attraction but there is also repulsion. And if you pull on these strings, everything comes together: sexuality, love, death, and much more.

Society is constructed around the concept of the family. In the traditional family order, each person has a precise role and binary understandings of gender are reinforced. I share Maggie Nelson’s idea (in the beautiful masterpiece The Argonauts) that the experience of carrying a child is a queer adventure, and that it can actually reveal the fragile construction of gender and gender roles. I learned from my research that all children before the age of five have a ‘ bisexualité psychique ’ and think that they can both have a penis and carry a baby one day. In many ways, I think that reflecting more deeply on birth and childhood development has the potential to change the world.

Marguerite Duras said that motherhood is a man-made ‘monstrous burden’. But what is monstrous is not motherhood itself; it’s what our culture, especially in the 19th century, has made of motherhood - as in it being this sanctified, self-sacrificial entity.

I think one of the biggest taboos in society is the role of the mother. There is little acceptance for the ways in which we are actually mothered by many people and many narratives. The sanctification of the mother reinforces the devaluation of women’s labor in society. This icon also severs mother’s labor from the public sphere, and keeps the labor of other caregivers, often women of color, hidden behind closed doors.

I read that only about a third of women in the past breast-fed. Common breastfeeding is a very recent practice and a product of the 19th-century. Very often the child was breast-fed by a wet nurse, either because the mother was working, or she was an aristocrat and either didn’t want to, or couldn’t. Both aristocrats and working class women were not specifically alone in caring for their children. 'The Republic of Motherhood', to borrow a phrase from Liz Berry’s collection of poems, is a constructed political category, and it’s one that needs to be dismantled and decolonized .

Is a more connected age helping break down these constructed ‘norms’? I think a lot of things are changing in this regard right now. Social media has enabled a shift from a more rigid, constructed reality to a more experienced reality which allows us to witness the experiences of friends and of those around us in new ways.

But parenting and care-giving doesn't only concern people who have children. Thinking about those dynamics allows us to address the value of care in society and the different types of care that exist too. Care is always a somewhat ambivalent thing.

Looking at the family, for me, is a way to address political and community ideas and issues. The foundational experiences of childhood is something that influences all of our later experiences in life. When we feel a sense of powerlessness politically, or in our relationship to technology and the media, there is an innate recall to the powerlessness we felt as children - having to bow to, or rebel against, the authority of our parents in the same way.

Sexuality, love, conflict- all our gestures in our relationships are learned through the experiences of childhood. Perhaps working on these topics allows me to drive towards their original form and look at the systems of relationships that we have, in order to consider the ways we project ourselves into the future.

Did you discern an attachment shift through the pandemic – like we’re maybe unlearning some of the traditional social mores around our relationships? Yes, totally. I think that’s a really good word - ‘unlearning’. In a way I feel there is a lot to ‘unlearn’ in relationships, in our private life, our public life and the space between the two.

For example, just think about the number of women who have died in childbirth. It’s much larger than the number of men who have died in battle. The rate of maternal mortality was higher in the past, but I don't know of any sculpture or monument built to commemorate or honor this fact.

If I was in government, I would start by making commissions to honor our domestic lives – a sort of acknowledgment of caring for children, cooking, and the activity of maintaining a house – these activities are so noble and worthy of admiration and there is no reason to devalue them. If we did this, I think there would be a real revolution in a way!

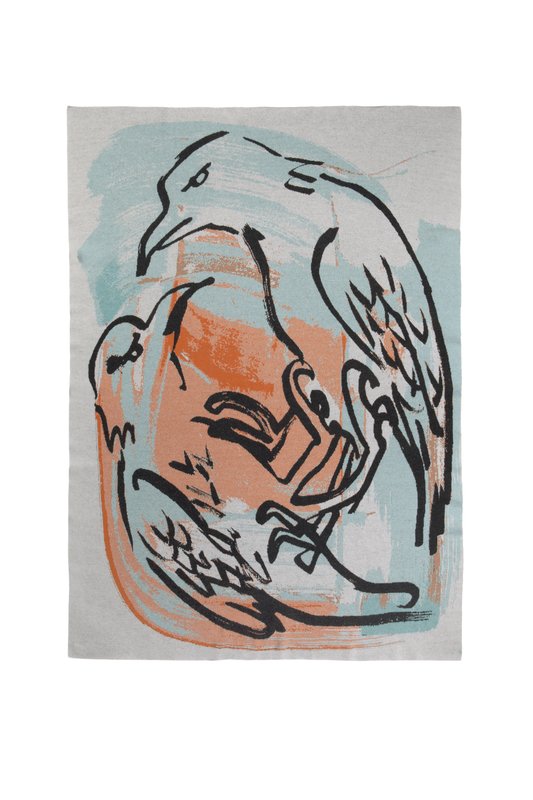

How do you stratify the various aspects of your practice? Across film, writing, painting and sculpture? It's a good question. In the past I have tended to work on kind of big, wide-ranging topics for my drawings, sculpture and films. In the last three years I’ve seen my practice come together around this articulation of the unspoken experience of the child - how experience that is beyond language informs every other aspect of our lives. This became a topic for sculpture and for painting and for drawing. I’m also working on a film now, but my recent work is the first time everything has converged.

With the drawings it’s easier if I start with an emotion. Usually I'll work with a list of titles. When I’m not drawing or if I don’t have enough time for it, I’m often listing titles that would incite the feeling of a drawing, rather than sketches. If I don’t have the space for it, I note down keywords and phrases on my phone. Sometimes they may be expressions that are like mysteries to me because they are not in my native language. Sometimes they are just groups of words. It’s never the description of a situation, because I noticed when I describe the image that I have in my head and I try to draw it later in the studio, it loses its magic. But if I write key words it almost functions like poetry, like a thematic poem. They are more connected. When I read them again it drives me back to this mysterious unresolved place.

It pricks your unconsciousness?

Exactly. I'll return to that unresolved place and rediscover the material that was triggering my desire to draw. I think it comes from a combination of things that I hear. When I was living in New York I loved to eavesdrop on strangers’ conversations and gather fragments of sentences.

There were funny expressions I would write down and also books I would read. But sometimes also lyrics of songs. For some reason one word will stick in my head - I don’t know why. For example, recently it was ‘Out of my hands’. I found this expression really interesting, because in English it can mean both, ‘I did it’ and ‘I’m powerless with it now’. It makes me think of the relationship artists have with creation, but also the relationship you can have with a child. As in, I have a child, but he’s out of my hands; he’s a person now. So there are so many implications in just one expression. I guess it’s because I’m not a native English speaker that I tend to project like this.

The choice of medium comes from different emotions. The impulse to draw comes from a rage or anger, and the impulse to write is similar to the one I make films with, which is more rational, more analytical. Sculpture always comes from a more playful place. In a way I feel like when I do sculpture I’m a child, when I draw I’m a teenager, and when I make a film I’m an adult!

You use a lot of bronze in your sculptures, is that to do with the tactility of the material or something else? For me, sculpture is related to the idea of substitute object, like a stuffed animal or toy that provides comfort. It can make us fell safe, but it’s also playful. I really like my sculptures to be touched – that’s why I like to use bronze. It’s an old school material but there’s something about how solid it is - it’s not super fragile. I like to see people interacting with the sculptures, because their tactility is a really important feature. In many ways, if a sculpture triggers the urge to touch, I feel it is successful.

Do you have a routine when it comes to creating? I dedicate a certain amount of hours to drawing - no matter what I have to do elsewhere. I recently noticed that I become an annoying person if I don’t draw! Partially out of respect to the people around me, I started to dedicate one day of the week to drawing, and I try to protect that day no matter what.

I’ve often thought about what actually happens to unborn thoughts. I wonder sometimes what happens to ideas if I don’t have the opportunity to do creative work for a long time. Where are they? Do they disappear, and are they replaced by new ones? Do they hang out and just wait for their moment to materialize? Relocating because of the pandemic, not having a studio for certain parts of the pandemic, as well as recently breaking my wrist made me think a lot about that.

And what conclusion did you draw? Ideas are just waiting for the right moment to materialize. I don’t think we lose anything. The only thing I feel I lose if I don’t work for a long time is maybe my confidence. And it’s something very precious of course. It’s almost like a gym or a compass. The quality of the gesture is very important, just like it is for an athlete, and the quality of the gesture is achieved through training and repetition.

You can buy Henrot's new print here , and view many more of her works here ; meanwhile, for a deeper meditation on just one theme Henrot raised take a look at the Artspace Group Show on mothers, here . Camille Henrot's show Mother Tongue at Kestnergesellschaft in Hanover, Germany , opened last month and runs through August.