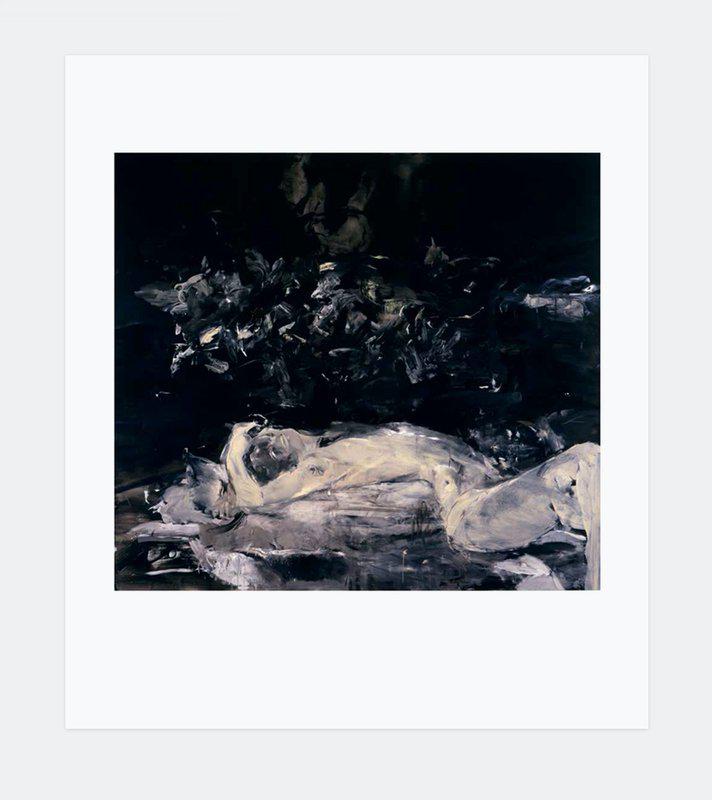

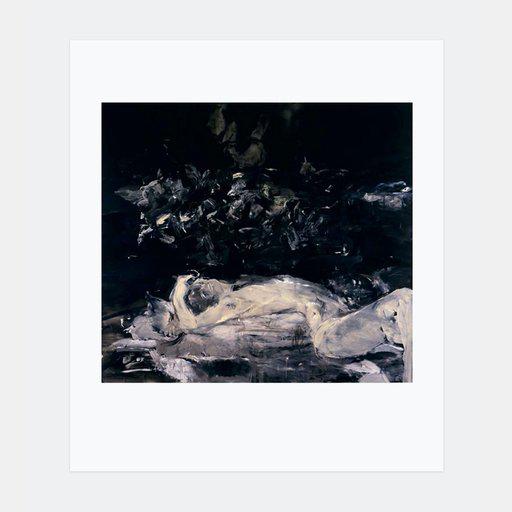

There’s something a touch ironic about Christina Quarles’s beautiful, new, exclusive edition Magic Hour (2016/2021). The work is named after that golden light of a summer’s dusk, yet Quarles’s own star is very much in the ascendant.

Artspace & Phaidon, in partnership with Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture , are very proud to offer this new work by Quarles, a Skowhegan alumna. Launched on the occasion of Skowhegan’s 75th Anniversary, proceeds from the sale of the edition benefit the program in honor of Skowhegan alumnus and Trustee David Beitzel (1958–2019) and Darren Walker.

The edition presents a no-longer extant fresco that Quarles created while she was at Skowhegan during the summer of 2016. Magic Hour showcases Quarles’ seductive and expressive technique and features polymorphous figures arranged in contorted positions bent to the constraints of the picture plane.

The work will debut during the preview of Frieze New York art fair, at the Skowhegan booth D4 on Wednesday, May 5 at 11am EDT. An edition of 50, the benefit print is priced at $2,500 USD each, with proceeds from the sale supporting Skowhegan’s summer program.

We spoke with the artist ahead of that debut, to understand how the work was created, why frescoes appeal to her, and how she’s been working since the pandemic’s onset.

What do you remember of making the source image for this edition and where did the title ( Magic Hour , 2016/2021) originally come from? This was a fresco I made while I was at Skowhegan. I took the fresco workshop that Skowhegan offers residents because, why not? But I remember thinking to myself that it would be a drag if I fell in love with making frescos because good luck folding that process into a typical studio practice. Well, for better or worse I did fall in love with making frescos and I’ve been longing to make one ever since.

It was created in 2016, the year it all began taking off for you. You had been at Skowhegan around this time? What do you remember of that time and experience?

I went to Skowhegan directly out of grad school. I drove directly from Connecticut to Maine with a fellow Yale grad and Skowhegan classmate in my wife’s old red pickup truck which we packed to the brim with art supplies, stretchers, canvases, and anything else we could grab from our studios at Yale–distinctly remember everyone cracking up at the sight of us when we first rolled up!

After three semesters of trying to figure out my painting practice, everything clicked in my final semester at Yale, so I was heading to Skowhegan ready to paint. I made a ton of work that summer. People would come into my studio and be like, you should relax, it’s summertime, and I would just be like, I’ve spent my whole life trying to make this work and I’ve finally figured it out, this is relaxing!

Christina Quarles - photographed by Elliot Orona © Christina Quarles, Courtesy Pilar Corrias Gallery, London and Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Christina Quarles - photographed by Elliot Orona © Christina Quarles, Courtesy Pilar Corrias Gallery, London and Regen Projects, Los Angeles

What were the themes you were beginning to investigate at that time and how have they progressed in the subsequent years? I began investigating the fundamental themes of my practice—ambiguity, legibility, intimacy—for ages. What has been newer for me, and what took years of failed attempts and convoluted projects, was the visual these themes would take. A lot of the gestural language of my work was well on its way by the time I was at Skowhegan, but there were some key developments in my painting that would happen that summer, specifically that afternoon I made this fresco.

As soon as I experienced making a fresco I was desperate to bring some of that fresco-feel into my paintings. One of the incredible things about a fresco is the vibrancy of color. You work with pure pigments and, unlike all other forms of painting, there is no binder mixed into the pigments which gives you such brilliant color. Up until this point, I was mainly using grey and black alongside some pops of color here and there. After making this technicolor fresco, I returned to my studio and everything looked so dull. My use of color really changed from then on. I also changed the way I prepped my surfaces after making this fresco to try and achieve a similar feel to painting on wet plaster. There is a moment in fresco painting where you are in the golden hour, a brief moment where, after working your surface for hours and just prior to the wall forever drying, you are able to lift layers and move around paint in this crazy way. I have been chasing that golden hour ever since and have been able to figure out some techniques that begin to mimic it in my work.

The positioning and depiction of the bodies, or bits of bodies, in your work is always so full of movement and a kind of tension, yet there’s a resulting kind of grace to the overall emotion they engender in the viewer – what inspires this ‘chaos’ of the human form? I’ve often referred to my work as representing a disorganized body in a state of excess. My aim is to paint portraits, not of looking at a body, but of being within your own body. I often think about how we are at a disadvantage of knowing ourselves as the cohesive and legible person we so readily observe in others. When I see another person, I see them in their entirety—a whole body with that which we prioritize above all else, a face. But, in that same interaction, I see myself as a jumble of limbs and my face remains just a memory of something I’ve seen flattened and reversed in the mirror that morning. Furthermore, in that same interaction, I am only seeing how this other person acts in the context of being in front of me. We all know that we behave differently throughout the day, and our behaviors and mannerisms change depending on the context we are in and the dynamic of our encounters. And so, yet again, because I know myself as existing on a continuum of fluctuating behavior and I know you always in the singular context of our relationship, your sense of cohesion will seem much greater than my own.

I find that we long for the cohesion we see in other people, we want desperately to be understood and to fit in, and we will often censor our full sense of self in order to achieve a sense of legibility. In my paintings the figures are always in a state of flux, a state of coming in and out of focus. There is an awareness of the boundary in my work, and the frame of the canvas and the planes in my paintings force the figures to contort in order to be contained. But there is also a sense of agency within the figures because once you realize the limitations of legibility, you can play with the expectations.

Lockdown may have perhaps increased the amount of time you have in the studio. Has it been a good time, in some ways? Have the fundamental qualities of our visually lived life–light, color, shade–come more to the fore? Does the outside stillness make your mind more restive, and if so, how does this affect your work? I was surprised how long it took me to find my routine while sheltering in place. Being a painter, I am used to spending my working days in isolation in the studio, so you’d think I’d be well-adjusted for lockdown, but instead I initially found working just as challenging as anyone. I eventually found the outlet of working in the studio to be crucial in my staying sane throughout the pandemic. It is a space where I can reconcile the incongruity between the stasis of being in one physical location with beauty and nature and serenity, and simultaneously projected into a digital reality in which I am instantaneously connected to global change, catastrophe, fear, and grief.

The planes in my work serve to both place and displace the figures they hold and I look for patterns and references that can take on multiple meanings, a sort of visual punning, to further complicate the location of the figures. Over the course of the pandemic, the patterns have given way to gradients of light. I am interested in the way that a gradient is something we find in both the color of the sky and the color of our computer screens. The location of a gradient is one that I have found particularly interesting in this moment where I find myself grappling with the cognitive dissonance between the subtle shifts of light in an LA sky and a rapidly changing world on my phone.

You’ve spoken of the patterns in your work as being quiet anchoring. Do you actually start with them on the canvass? How does a painting take shape for you, where does it begin and how do you know when it’s ended? Do you relish controlling the gestures and movements on the canvas? The composition gets determined as I work through the painting—it’s not something that’s decided beforehand. I begin with a series of fragmented gestural brushstrokes that come from a sort of muscle memory developed from decades of figure drawing. I resist the urge to complete the form with these initial marks and instead will interrupt the process by stepping back and looking at what I’ve laid down. I try to challenge myself to connect these fragments in a way that was not my initial intention, to invent new poses than those that I’ve seen before.

There is always a back and forth between my intention and what is actually in front of me. Because I am not working from sketches, the painting is not trying to be anything other than what it becomes. I am informed by both my intended marks and those that happen to occur, like drips or bleeds. Eventually, the figures take shape and I’ll photograph my work and bring it into Adobe Illustrator to work out the patterns and planes. Though it is digital, there is still that same interaction between intention and actuality and often an unintended glitch in my digital drawing will catapult a new direction for the composition moving forward.

With this process, the figures are painted before the patterned planes that situate them. This leads to there often being a contradiction between the image and the materiality—the foregrounded figures are often made up of thin washes and exposed canvas, whereas the background planes are made up of thick applications of paint that rest above the canvas’ surface. This is one of those things you can only fully appreciate when looking at the work in person, but I find that this tension between what we see and what we know aligning nicely with many of the themes in my work.

You are included in Phaidon’s new drawing survey Vitamin D3. Is there a difference between painting and drawing for you and, if so, what is its importance? And, for you, has the distance between the two mediums changed as the years go by?

I think of my practice as being rooted in drawing—I’ve been drawing far longer than I’ve been painting. What changes between my drawings and paintings is scale. I see my paintings as existing in this shoulder scale of making, one which is best accommodated by the wide range of materials and tools found in painting. My drawings are more in a wrist scale, one that is best expressed with a simple fountain pen.

Drawing, for me, is really related to thinking. Maybe it’s because I draw in the same scale and manner in which I write, but whenever I am drawing, I feel like there is a link from my brain to my hand. Painting can be very physical, and it is something you build upon which, to me, places it in the realm of time and space. But drawing feels uniquely connected to the mind and I maintain a drawing practice to have this direct access to a flow of thought.

Tell us something about yourself that might surprise people who think they know you through your work! I hate stretching.

Magic Hour , 2016/2021, a digital archival print on Moab Entrada 290 gsm paper by Christina Quarles ( Edition of 50 plus 5 APs + B.A.T.) is available here for $2,500.