Ever since Jeffrey Deitch returned early last year from his controversial stint as director of MOCA in Los Angeles, the art world has been wondering about his next chapter. There have been signs of an attempt to re-create the vital infusion of art, design, fashion, nightlife, and street culture that was Deitch Projects in its earlier incarnation, with a tribute show to the 1980s nightclub Area (held at his protégé Kathy Grayson's Hole Gallery) and an exhibition of street art in Coney Island, but also reports of a lucrative consulting practice and a renewed focus on his time-honored trade in the secondary market.

As 2015 draws to a close, however, a clearer strategy is starting to gel—one that makes use of both Deitch’s private-dealing acumen and his status as an impresario of pop-up shows and special events. For Art Basel Miami Beach, for instance, he has teamed up with none other than Larry Gagosian on an exhibition, “Unrealism,” that will fill the atrium of the Moore Building with figurative painting and sculpture from the 1980s (Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente) to the right-this-minute (Jamian Juliano-Villani, Sascha Braunig).

This clearly sales-oriented, object-centric exhibition may sound a bit staid for a Deitch event in Miami—this is, after all, the man who invited Miley Cyrus to peform at the Raleigh last year. But it also capitalizes on a new wave of figuration by younger artists who have tired of neo-formalist abstraction (a topic we have been covering in our conversation series surroundingPhaidon's new book Body of Art). And in characteristic Deitch fashion, it will incorporate a festive performance: an exuberant, costumed parade through the Design District by the voguing video artist Rashaad Newsome.

Meanwhile, Deitch is also working on “Overpop,” a touring international group show scheduled to debut in Shanghai in 2017 that explores Pop influences in Post-Internet art. And closer to home—much closer, in fact—he has big plans for the year ahead. Deitch sat down with Artspace’s Karen Rosenberg at his Grand Street space to talk about the resurgence of figurative art, the evolving downtown art scene, and what’s next for him and his gallery.

What inspired you to do a show of figurative painting and sculpture? At first glance, this exhibition looks a lot more conservative than your usual programming.

This has been an interest of mine going way, way back. In 1984, I organized a big exhibition at P.S.1 called “The New Portrait” that took up the entire second floor. It was a portrait salon, and Andy Warhol helped me organize it. We had one room that was Pictures Generation artists like Robert Longo, a Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring room, photography rooms. In the center, we had a fantastic display of Warhol’s portraits of artists. So I’ve been interested in this from the beginning. Figurative art is like the novel—it’s reinvented by every generation, and gives us insights into how artists are perceiving life today.

I had planned, at MOCA, a show on new figurative painting. If you’ve gone to the Museum of Modern Art over the past 15 years, or most other American museums, you’ve hardly seen any figurative painting on view. That’s really what most artists do, and what the general public generally expects out of painting. They relate to it. I’m as steeped in conceptual art as anyone—I worked at the John Weber gallery in the ‘70s—but it’s something I was thinking about when I went to a museum. There’s hardly been an ambitious exhibition of new figurative painting in any American museum in a long time.

Can you tell me more about that unrealized MOCA show? How close is “Unrealism” to your original vision?

At MOCA I was planning on doing it with Alison Gingeras as a guest curator. I loved the show that she did at the Pompidou, more than 10 years ago, called “Dear Painter”—the title is taken from Martin Kippenberger. Alison is quite interested in a kind of counter-history of figurative painting, and she notoriously included Bernard Buffet in that show. The theme that Alison was interested in was “wrongness” in figuration. It started with Giorgio de Chirico, Francis Picabia, other figures like that, and went into the present.

We never were able to do that show. But I still had this desire to do a really strong show on new figurative painting, and I just adapted it to this commercial situation—a show that’s supported by making sales, which we do in this sector. My original title for the MOCA show was “Unrealism,” because I love titles like this that have some ambiguity. Alison preferred “Wrong Figures,” so that was our title there, but here I went back to “Unrealism, and it’s a much more compact history, because for a one-week show we can’t be borrowing de Chiricos.

Were you also thinking about the ideas from your 1993 touring show in Europe, “Post Human”? That exhibition, which focused on the reshaping of the body through futuristic technologies, seems so prescient now in our age of Post-Internet art.

“Post Human” is the inspiration for another show I’m working on, “Overpop.” It’s great that it’s had this second life. I’ve done so much, and most of it unfortunately just disappears into the ether. You hope that cumulatively, it made some statement.

There are number of artists, like Maurizio Cattelan, Vanessa Beecroft, and the Chapman Brothers, whose work comes right out of “Post Human,” and they actually acknowledge that. And, subsequently, Urs Fischer was very influenced by the show, even though his work is not really in this vein.

What’s very gratifying for me is that when I first met Josh Kline, I said, “By any chance did you hear of a show I did called ‘Post Human’? And he said, “Of course!” He even has the book. It’s a real reference for Josh and a number of other artists, who somehow got hold of the book at a used bookstore.

I want to hear more about “Overpop.” But first, who are the artists in “Unrealism”?

This show was also inspired by a group of very exciting young figurative painters I’ve discovered over the past few years. In New York there’s Ella Kruglyanskya, Jamian Juliano-Villani, and Emily Mae Smith, and, in L.A., Tala Madani. In Germany, there’s Jana Euler. In Maine, Sascha Braunig. There’s Jonathan Gardner, who’s just moved to New York from Chicago. I think some of these artists are exceptional talents, and a perfect example of reinventing figuration to connect with contemporary experience.

These artists are very knowledgeable about historical precedents. They’ve studied traditional technique, but it’s very, very fresh. Ella, Tala, and Sascha all studied for their MFAs at Yale, and they intersected with Kurt Kauper, who’s an artist I used to show and a great teacher. Others like Jamian, who went to Rutgers and is much more self-taught, are looking at unexpected sources—monster magazines, old Playboys, things like that.

I’m very excited about these artists, and if I could get enough material I would do a show just with them. But they’re so in-demand, and just to get what we got was a real achievement. I thought it would be interesting to put them in a context with several other generations of contemporary figurative painters, who are continuing to do vital work and are changing with the times.

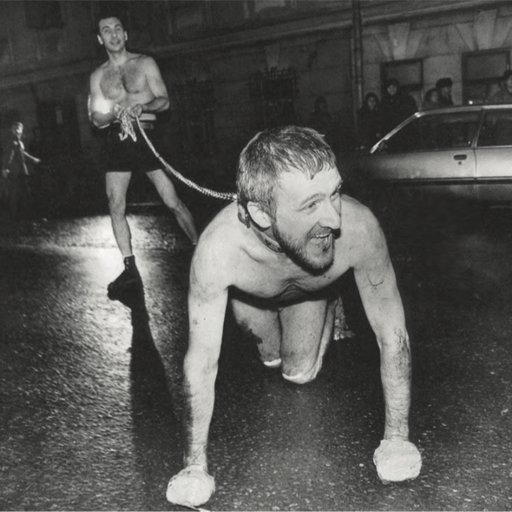

Jamian Juliano-Villani, The Entertainer, 2015. Courtesy of the Artist, JTT, New York and Tanya Leighton, Berlin

Jamian Juliano-Villani, The Entertainer, 2015. Courtesy of the Artist, JTT, New York and Tanya Leighton, Berlin

Who are some of those other painters?

We start with the ‘80s generation—Francesco Clemente, George Condo, Julian Schnabel, Richard Prince. Then, from the ‘90s generation, John Currin, Rachel Feinstein, Elizabeth Peyton, Karen Kilimnik, Cecily Brown, and others. We have others who go beyond the New York group, like Henry Taylor from Los Angeles. space lends itself to sculpture as well—the entrance will be an Urs Fischer candle portrait of Michael Chow, which will burn during the show, and we’ll have two great Duane Hansons.

What about the many artists who combine figuration and abstraction? How strict were your parameters?

It’s such an open, big topic, but we wanted to keep it as coherent as we could. I’m not one to make restrictions on media, but rather than having all kinds of media—photography, video, immersive installations—I decided to keep it a tighter show. It’s painting, and a small amount of sculpture, and most of the painting is figurative. There’s one painting that is not—it’s a Dan Colen interior. It’s always good to have one thing that throws it off.

Will there be performance?

Yes. The opening will have a procession and performance by Rashaad Newsome. I got the idea from a video of a procession he did in New Orleans, called King of Arms, which I thought was incredible. He’s very involved in the new vogueing scene, and we’re bringing voguers down from New York. We’re going to have a marching band from Miami. We’re doing a procession that will start at the de la Cruz space and go through the Design District. It’s a big challenge, because there are going to be a lot of cars coming in and we have to figure out the whole traffic pattern. But it’s going to be worth it, because it’s going to be very exuberant. I’d like to do more, but it’s a short show. If I were to do the show in New York, there would be more of a performance component.

Do you see performance in general, particularly some of the performances you’ve done at your gallery—for example, Colen and Dash Snow’s “The Nest”—as part of the figurative tradition?

Oh, absolutely. Part of the revival of figuration, in the early ‘80s, came out of performance. When I was the American editor of Flash Art years ago, we did a whole issue of performance into painting. It was a big topic then—the mainstream galleries were conceptual/Minimal, and there were a few galleries showing photorealism, but you weren’t even allowed to talk about going there. There wasn’t much of a place to go for the younger generation.

My whole group would go to performances at the Kitchen and CBGB when that started up, and a lot of the people who became painters at that stage were in bands, doing performance art, making vanguard film. Somehow it all converged into a more iconic image, into painting. Performance is so crucial to that shift—the dialogue between Cindy Sherman and other artists in her circle like Longo or David Salle, who went to CalArts with all the dance and performance art and turned it into paintings. That’s very, very important. Today, for many painters the references are film, TV, the videos that people send around on social networking—that’s very much part of the vocabulary.

In a recent interview with the New York Times you spoke about the appeal of humanism at this moment, when artists have been preoccupied with "inside-art issues." Can you elaborate on that?

Even though I have a whole history of exploring figuration, I’m equally interested in abstraction. The most important show that I did at MOCA, for me, was “The Painting Factory,” a survey of new abstraction. So it’s not that I think this is better—what happens is that a chapter gets completed; it plays out. There’s a lot of achievement, when you look at Julie Mehretu, Mark Bradford,Wade Guyton, Tauba Auerbach. But now you see that the field is diluted by second-tier abstractionists—I don’t want to mention any names—who are using printing techniques and kind of a conceptual story, and it’s just not as good.

It reminds me of Post-Minimalism when I came into the scene in the ‘70s, after Robert Ryman and Robert Mangold and Brice Marden—there were dozens of artists doing Minimalist-type painting, and most of it’s completely disappeared. I just see that something similar is happening with the abstract dialogue—it’s played-out. Younger artists recognize that, and ambitious people are going in a fresh direction. There are cycles. After the ‘80s, people had had it with fabricated, market-ready sculpture, and then there was more of the ethereal—Felix Gonzalez-Torres installations, things like that.

You can see the next cycle starting in the current “Greater New York” survey at MoMA P.S.1 and in last spring’s New Museum Triennial.

That’s right. The interest in the figurative never goes away, and I love that it reappears in a fresh way that reflects contemporary experience.

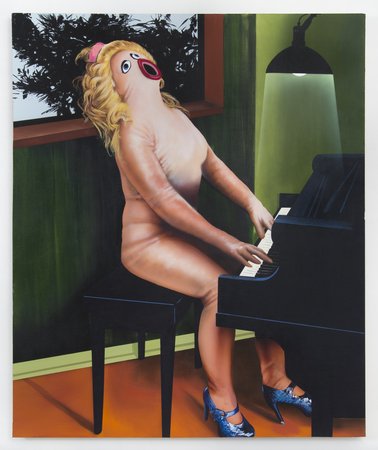

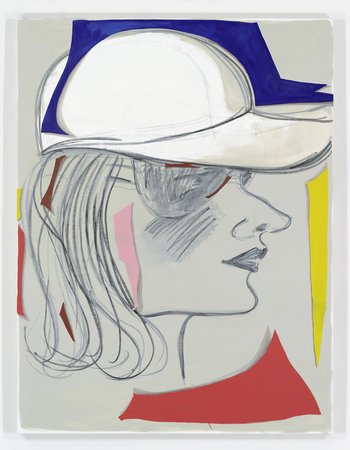

Ella Kruglyanskaya, Profile in Hat With Cut Papers, 2015. Oil and oil stick on linen, 84 x 64 in. Collection of Craig Robins, courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown, NY

Ella Kruglyanskaya, Profile in Hat With Cut Papers, 2015. Oil and oil stick on linen, 84 x 64 in. Collection of Craig Robins, courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown, NY

How exactly are these younger artists you’re championing in “Unrealism” making the figure new again?

They’re all different. Ella is probably the most traditional—she’s looking very carefully at Picasso and Matisse, and even that is somehow fresh because that has not been so much of a reference for vanguard painters. But there’s also something that connects with fashion illustration and the expanding art platform and the confusion of what’s art and what’s fashion and what’s popular culture. She’s involved with that. I see references to Picasso, but I also see references to fashion illustrators like Antonio Lopez.

Jamian is interested in Surrealism—in her work you see Yves Tanguy, and also Mexican women Surrealists like Remedios Varo. She’s looking at that more Feminist art history. But she’s also into weird non-art stuff, like H. R. Giger science fiction illustration. She’s brilliant at finding all these obscure sources, including some artists who were neglected but are coming back, like Christina Ramberg—she has every book on Ramberg. She addresses something very contemporary, which is increasing confusion between fine art and popular culture. It’s all colliding. Her studio is this crazy mezzanine in somebody’s silkscreen shop. If the building department ever came, people would get arrested! You know how artists have to work in New York, even successful ones.

How you think the conditions for making and showing art in New York have changed in recent years? Did anything surprise you when you came back from California?

In five years, the studios have gotten more and more miserable. In the ‘70s, people in my circle had entire floors in SoHo and Tribeca that were really cheap—young people that had just arrived. Then the ones who still had their leases divided them up into warrens. Then people had really nice places in Williamsburg, but that fell apart for artists pretty quickly. Then it was nice places in Bushwick. And now it’s like you’re in some institution, where some real-estate sharpie has rented a floor and divided it into 30 cubicles. It’s like you’re in some state hospital. Everyone has a cubicle, but they keep the doors all shut.

It’s much tougher to be an artist here, and I really admire people for being here and pushing it. It’s not as pleasant as it was for my generation. People say, “Let’s all move to L.A,” but it’s still so dynamic in New York. With this group of artists I’m looking at with the new figurative painting, there’s more talent in New York than L.A. It’s the dialogue, the social networking of people seeing each other in person and talking and hanging out. And the standards that are here—you can’t have a half-baked exhibition and keep your position. It’s changing in L.A., but until recently people had half-baked exhibitions, and it was sort of still ok.

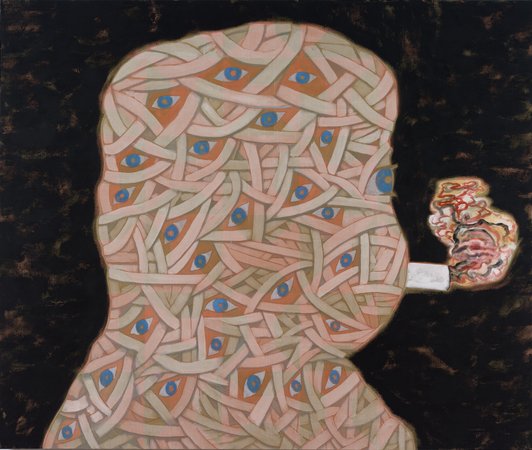

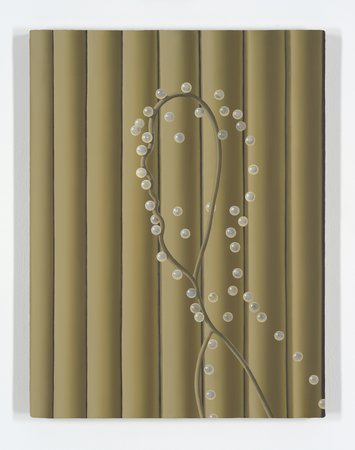

Sascha Braunig, Marker, 2015. Oil on linen over panel, 25 x 19 in. Private collection, courtesy of Foxy Production, NY

Sascha Braunig, Marker, 2015. Oil on linen over panel, 25 x 19 in. Private collection, courtesy of Foxy Production, NY

Did working within that institutional structure of MOCA change anything about the way you organize exhibitions?

It’s so ironic, but when I did the shows here I never had to think of commercial considerations. We always had something going that would help to pay for it. My business philosophy was, if you do something inspiring, someone is going to want to buy something. And it worked.

In a museum, there’s more compromise. There are certain things you can’t include because a sponsor might find it offensive. Then, say there’s an important patron of the museum who collects an artist.... All the museums say, “Oh, we don’t do this,” but if your big trustee is a big collector of this artist, well, you basically have to put that artist in. You don’t really advertise it, but that’s the reality.

But the thing that really astonished me is that if you’re a museum director and, increasingly, a museum curator, the majority of your time is spent fundraising. I was quoted someplace saying that when I had Deitch Projects it was 90 percent art and 10 percent business, which is pretty accurate. At the museum, it was 90 percent business and 10 percent art. It was just constant, relentless fundraising. A certain kind of museum show simply won’t find a sponsor, but another kind is more appealing to the public and a bank will sign up. I’m used to working without compromise, and it was interesting going to a museum where there’s much more compromise.

“Unrealism” is a collaboration between you and Larry Gagosian—how did that take shape?

I’ve known Larry since 1979. I met him when he and Anina Nosei had a gallery in a loft on West Broadway across from the building with Castelli and Sonnabend, and they showed Salle who was a friend of mine. In the early ‘80s, I used to go out to L.A. frequently to attend the openings of shows of friends of mine, like Basquiat and Kenny Scharf. I got to know him in a casual way, not just a business colleague way. We were both protégés of Leo Castelli—we had that in common. And we’ve worked with many of the same artists over the years: Basquiat, Jeff Koons, Cecily Brown.

People say, “Isn’t he your competitor?” But I never thought that way. This is a very big platform. If some artist decides to leave me and go to Gagosian, it’s not the end of the world. It opens up the opportunity to develop someone else. It goes both ways—there are artists like Salle or Clemente who used to be with Gagosian and then they worked with me. There are never any recriminations or lawsuits. I’m relaxed about this—I’m very confident in what I can do. I never thought of this field as a zero-sum game.

You two do have very different business strategies, however—he has a global franchise model, whereas you have focused on New York and just a couple of spaces.

For me, it’s not business first. I’m much more about using the business structure to support my curatorial projects. I’ve found that the market system is a great system to support radical art and artistic innovation.

What do you make of the business challenges of running a smaller or mid-sized gallery today, especially in New York? There are the staggering expenses of participating in art fairs, on top of rising rents.

Just like the artists keep coming, the ground-level galleries keep coming. Artistic entrepreneurship is thriving here. Some of the most exciting places to encounter art in New York are the basement of Ramiken Crucible, the little storefront of JTT, and Real Fine Arts in Brooklyn underneath the highway. The artists who show at these places, and the people who want to buy their work, don’t need a gigantic, slick, super-expensive gallery. I’m more stimulated by the experience of going into this alley behind the liquor store to get to Ramiken Crucible. The serious people love it—there’s a sense of discovery and authenticity, and a number of artists also appreciate that.

Some artists are waiting for that invitation from the mega-gallery. Other galleries want to do something with them, and they’re holding back. And some of the mega-galleries do a really good job. But is Oscar Murillo’s career going to be more interesting and dynamic and rewarding to him by being with David Zwirner than if he had stayed with Carlos/Ichikawa in London, where he’s hanging out with other artists of his generation? It’s an interesting question. I’m always more enthusiastic about the model where the gallerist is about the same age as the artist, and they grow up together and establish something together.

Cecily Brown, The Homecoming, 2015. Oil on linen, 77 x 97 in. Courtesy of the artist

Cecily Brown, The Homecoming, 2015. Oil on linen, 77 x 97 in. Courtesy of the artist

One of the strategies that you’ve been working with is to have less of a gallery presence and to focus on pop-up exhibitions.

Yes. It’s a much bigger reward for me to create a thematic exhibition, instead of just running as fast as I can on a treadmill to create 30 shows a year, which we used to do. We did “Unrealism” pretty quickly, although it’s a major effort. With “Overpop,” I’m taking more time. This is more what I want to do now, to do projects that take some time and have a book attached and that make a bigger impact. Also, rather than just representing artists I like, I can work with all galleries. With “Unrealism,” we’re getting wonderful collaboration with everybody. That’s something I was able to take advantage of at the museum, and I wanted it to continue. The show is a great collaboration, not just with Gagosian but with Zwirner, with Hauser & Wirth, with Jack Shainman, with many other galleries.

What do you think is the future of SoHo as an art neighborhood? There are very few galleries left in the area, and some of the ones that remain are consolidating or closing. Meanwhile, the Lower East Side is booming.

SoHo has a new dynamism, because of the Lower East Side. You can just walk right down Grand Street—it’s a 10-minute walk. It’s a really central area for shopping, restaurants. There’s Chanel here, but also there’s H&M, Uniqlo. There’s something for everyone, no matter what your income level. I’m very populist, so I like that it’s very central, very accessible. Every subway goes here.

The other new development, besides the Lower East Side galleries, is Condé Nast and TIME and Fox going to the World Trade Center area. It’s one subway stop on the E train, and you’re here. You can easily come here at lunch hour if you’re working for Vogue.

So I’m very happy—I’m not going anywhere. In August, I’m going to take back the Wooster Street space back. I had given a special five-year lease to the Swiss Institute—I was planning to be away, but I had always planned to take the space back.

So you’ll operate it as a gallery again?

Yes, but again it’s not like we represent this or that artist—it would be thematic shows, or… I have plenty of ideas. Not for month-to-month shows, but maybe shows that would be on for a couple of months. And then we would use this space [at 76 Grand Street] more as an office and showroom.

Is Brooklyn, where you had been looking for gallery space last year, off the table at this point?

Yes, I’m focusing here. I tried to make a deal to bring in a partner who I was connected with to buy a half-interest in a big property in Red Hook, and out of that I would get an exhibition space. It wasn’t completed. Then I got this building back, and then I was invited to do this outdoor project in Coney Island. So I don’t really need it now.

Can you tell me more about “Overpop”?

The theme of “Unrealism” is very straightforward—the winds are shifting, and there’s some very fresh figurative painting, and we’re seeing this cycle just like we did in 1980 or ’82—a new interest in figuration. “Overpop” is much more complicated. In a way, it’s my sequel to “Post Human.”

When I see something that’s out there that hasn’t been fully articulated yet, that plenty of people are talking about, I want to rise to the challenge—can I define what is important in this moment? I’m very interested in tendencies in art that coincide with trends in society and science. With this “Overpop” moment, we see this convergence between artistic trends, social trends, technological trends. There’s something really interesting there that can help us to understand and define our moment by looking at art.

For me the title is even more important than the essay. It’s crazy how few people actually read your essays, but everybody knows the title. With this group of artists, there’s a lot of debt to the foundation of Pop art, to Warhol and other artists in the Pop arena. There’s also this confusion between art and popular culture. There are artists in “Overpop” who work directly in popular culture—like Miranda July, or Harmony Korine. Spring Breakers is pop culture, but it has amazing artistic imagery and concepts.

Where exactly are you doing "Overpop"?

It’s going to open in Shanghai. We’re talking with an American museum—I hope it’s going to happen. Then it’s going to the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Foundation in Turin—they’re very astute, they collect a lot of these artists. And we’re doing a book, with [Karma's] Brendan Dugan.

What else are you working on? I heard you were planning to do the “Disco” show you had wanted to do at MOCA.

That’s all conceived and ready to go. But what I decided is that the “Overpop” show is very timely—I have to do it now. The disco show, it doesn’t matter whether it’s done this year or three years from now—it’s more historical, and people will love it then. So I put that off to do “Overpop”— I can’t delay that show, because it’s of this moment.

How would you characterize this current moment in the art world, aside from the issues in "Overpop"? What else is on your mind?

From my perspective, this whole gigantic structure of art fairs and auctions has become excessive. There will probably be some sort of correction, because it’s just too extreme. But I’m also an idealist, and I love it that the art audience has become so much bigger. I do believe that art enhances people’s lives, that art at its best can create more open and tolerant attitudes and understanding between people of diverse backgrounds. So I think it’s good that the art world is much bigger.

I also don’t want to be a curmudgeon and say, “It’s ruined now,” or that the ‘80s was the golden age. In the ‘80s we had to listen to the people from the ‘50s, who thought that Leo Castelli had ruined the art world! The big message is, contemporary art used to be quite marginal in the general culture and the economy, and now art is much more in the center.

RELATED LINKS

Order Phaidon's Body of Art, a survey of figurative work across the span of art history