As we discussed with Rashid Johnson in our interview earlier this week, artists need not show the body in order to reference it. Crucial innovations over the course of the 20th century (think Abstract Expressionism, Land Art, and conceptual art in many of its forms) proceed from the idea that art, at its core, is a record of a person having done something at one point or another. Whether this “something” is worth pondering is, of course, another question entirely. These eight works, each excerpted from Phaidon’s new book Body of Art, show some of the most celebrated instances of artists hinting at (as opposed to simply representing) the human body.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon'sBody of Artand buy the book.

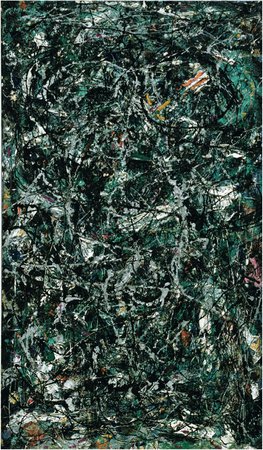

FULL FATHOM FIVE

Jackson Pollock

1947

Full Fathom Five at first appears to be a chaotic jumble of drips, smears and apparently random paint marks, with detritus such as nails, coins, matches and cigarette butts embedded into its highly textured surface. It is one of first paintings in which Pollock (1912–56) employed his famous "action-painting" technique of pouring, flicking and dripping household paint onto a canvas on the floor as he walked around and across the picture. This method of painting involved the artist’s whole body, not just the hand, and the final composition is a record of his spontaneous physical gestures. Buried deep beneath the thick layers of paint, however, there lies a different body. An X-ray has revealed the presence of a figure, standing with parted legs, whose pose ostensibly determines the placement of the found objects across the painting’s encrusted surface. The final composition is actually the result of the extensive over-painting of an earlier, semi-figurative work. Pollock’s choice of greens, blacks and flecks of white evoke the ocean’s watery depths. With a body lying beneath this murky brine, the work’s title is apt; suggested by a neighbor, it is taken from a verse of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which a drowning at sea is described.

ANTHROPOMETRY: PRINCESS HELENA

Yves Klein

1960

To create his Anthropométies, the French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962) turned naked women into "human paintbrushes." Dressed in evening wear, the artist instructed the women to cover their breasts, stomachs and thighs in blue paint – his own International Klein Blue – and directed them to make imprints of their bodies on sheets of paper hung upon the wall. The action was first staged before a live audience at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain in Paris in 1960. Musicians playing Klein’s Monotone Symphony (a single note played for twenty minutes, followed by twenty minutes of silence) accompanied the performance, and the audience was served blue cocktails. Klein emerged in the early 1950s as a radical young artist whose new techniques and monochrome experiments questioned the very nature of painting and art creation. Today, opinions on the Anthropométies vary dramatically. For some, the works demonstrate a crucial moment in both the history of painting and performance art, in which the act of mark-making is fully separated from the artist. Others criticize the dubious power dynamic between the "human paintbrushes" and the dictatorial artist, noting that thus employed, the female body is an object for observation no different to the odalisques of old, expressing and reinforcing outmoded patriarchal values.

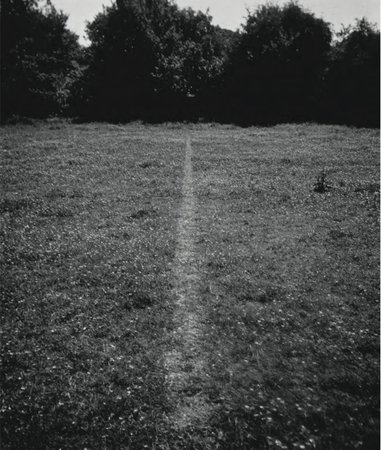

A LINE MADE BY WALKING

Richard Long

1967

In this photograph a straight line of flattened grass neatly intersects a field. The line records the path of the artist’s body as he traipsed back and forth through the landscape. Long (b.1945) made this work while he was still a student at London’s Central Saint Martin’s art school. Catching a train from Waterloo station one day, he travelled southeast until it reached the countryside. Continuing his journey on foot, he stopped at a nondescript field where he began walking up and down its length until an impression had been made, and then photographed the result. With this simple gesture, Long elevated the act of walking to the status of high art, challenging the notion of art as a tangible commodity. For like the artist’s body, the temporal line of trampled grass soon vanished from the site. The intervention has been preserved only by Long’s photograph, which ironically has itself became the physical, and marketable, embodiment of the work.

ABORIGINAL MEMORIAL

Ramingining Artists

1987-8

This installation confronts the traumatic history of racism, brutality and attrition inflicted on Australia’s indigenous population and their culture. Created to coincide with the bicentenary of Australia, commemorating the arrival of the First Fleet of convict ships from Britain, it consists of 200 hollow log bone coffins, one for each year of European settlement since 1788. Made by a collective of artists from Ramingining in Central Arnhem Land, the placement of the coffins reflects the serpentine form of the river Glyde, which flows through the Top End of the Northern Territory to the Arafura swamp – a passage of cultural significance for the Ramingining community. Inspired by the mortuary ceremony particular to that part of the country, the coffins traditionally ensure that the spirit of the deceased finds its way to the land of the dead. A tree, hollowed out by termites, is cut down and painted with totemic designs. Placed upright, it is filled with the bones of the deceased and left to the elements. In this installation, however, the logs are left hollow and stand as witnesses to history – a reminder of the lives and land lost under colonial rule, and the country’s ongoing issues surrounding reconciliation.

UNTITLED (PORTRAIT OF ROSS IN LA)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1991

A large, colorful pile of wrapped sweets sits in the corner of the gallery. The confectionery is free to take, and as visitors help themselves, the heap slowly diminishes. Gonzalez-Torres (1957–96) has seemingly created a fun and tasty artwork, yet the shiny wrappers contain a somber message. The initial weight of the sweets is 175 pounds (79.3 kg), the healthy body weight of the artist’s partner, Ross Laycock, who died from an AIDS-related illness in 1991. The dwindling pile evokes Ross’s weight loss and deteriorating condition before his death. Gonzalez-Torres created this work at a time when the subject of AIDS was still taboo, and, as a metaphor for Ross’s failing body, the work implicates the viewers who have unwittingly participated in its demise. The piece brought the AIDS crisis into sharp focus, challenging society’s attitudes and admonishing those who chose to ignore the epidemic. Gonzalez-Torres specified that the sweets should be replenished each morning, and so, metaphorically, Ross’s body is returned to health over and over again, in a form of everlasting life.

MY BED

Tracey Emin

1998

An unmade bed with dirty sheets is surrounded by the detritus of a chaotic, unhinged life: cigarette stubs, the remains of take-away food, used tissues and bandages, underwear soiled with menstrual blood, a battered child’s toy, contraceptive pills, used condoms, a pregnancy test kit and empty vodka bottles. Tracey Emin (b.1963), known for her autobiographical and confessional art, has described how in 1998 she spent four days in bed following the collapse of a relationship: "I was asleep and semi-unconscious. When I eventually did get up, I had some water, went back and looked at the bed. I couldn’t believe what I saw: this absolute mess and decay of my life …" By turning her bed into art, she challenged the viewer to confront transgressive subjects including mental illness, female promiscuity and sexual disease, acknowledging that while beds can be places for positive life experiences associated with the body dreaming, sleeping, sex and birth – they are also sites of illness, confinement, loneliness and death. The work’s dramatic and sordid physicality points to the extremes of the oversexed, alcoholic-fueled "fallen woman", but removes the judgmental quality of earlier artworks that touch on the same theme.

EN EL AIRE (IN THE AIR)

Teresa Margolles

2003

The initial pleasure of entering an empty gallery space dotted with a constantly renewed supply of glistening soap bubbles, projected towards the ceiling before floating down on gentle currents of air, is quickly undermined upon reading the information provided. The label explains that the water from which the bubbles are being made was used to wash corpses before an autopsy. Despite being thoroughly disinfected, the stigma of death turns the beautiful into the horrifying, joy into revulsion. The fact that bubbles are often created for children’s amusement and diversion particularly dismays some parents whose offspring are too young to read, or who have not yet learned such culturally constructed notions of disgust. Teresa Margolles (b.1963) has made several installations using disinfected morgue water to explore and reveal taboos around the dead body. Water is essential to all life forms, and its supply on Earth is finite and is therefore constantly recycled. Yet while we comprehend that all water, including that flowing from morgue drains, is ultimately part of one ecosystem, we are usually able to rationalize or suppress our abhorrence until, as with this work, we are presented with evidence that brings the "unclean" slightly too close for comfort.

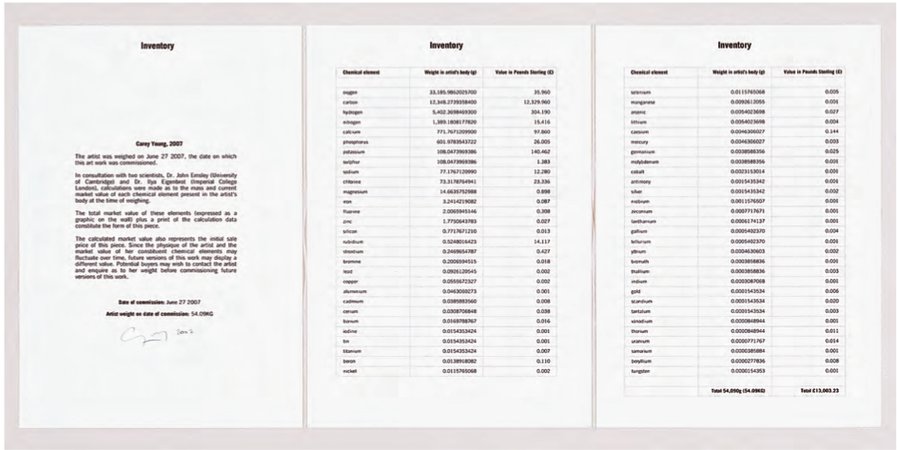

INVENTORY

Carey Young

2007

How much is a human body worth? This is the question that Carey Young (b.1970) sought to answer on June 27, 2007, the date on which this artwork was created. She had herself weighed, and in consultation with two scientists calculated the mass of each naturally occurring element present in her body. The current market value of each element for that day was combined to create the sum of £13,003.23 (US $19,747). This figure, her "total market value", is displayed on the wall and is accompanied by the calculation data. A table lists all 58 elements present in Young’s body, including oxygen, potassium, sodium, magnesium and even gold. Young continues to make versions of this work. Since her body weight and the market value of its constituent elements fluctuate over time, each version displays a different price. As an unconventional self-portrait, the work links Young’s body with the commodity markets – a wry comment on the way in which Western art and culture objectify the female body.