For his conceptual photography series “Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008,” the American artist Hank Willis Thomas took advertisements featuring or directed at African-Americans and simply removed all of the accompanying text. Bereft of branding (an ongoing focus in Thomas's work) and product copy, the models in the appropriated ads took center stage; the series became a meditation on the ways in which black bodies have been represented and commodified in the decades between the end of the Civil Rights Era and the election of Barack Obama.

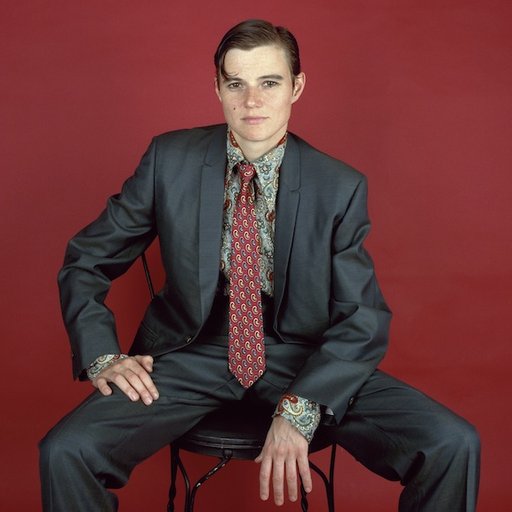

Hank Willis Thomas. Photo: Andrea Blanch

Hank Willis Thomas. Photo: Andrea Blanch

This process of isolating and then recontextualizing images in one graceful gesture has continued to be central to Thomas’s approach. Although he’s recently moved away from photography and towards installation and sculpture, he still thinks about framing and perspective when composing his pieces (which deliver a subtle but searing critique of popular depictions of black identity). The results are understated yet innately confident conceptual works that have earned places in the collections of the Whitney, the Guggenheim, the Brooklyn Museum, and other institutions.

As a part of an ongoing inquiry into the place of the human body in contemporary art (occasioned by the release of Phaidon’s new book Body of Art), Artspace’s Dylan Kerr spoke to Thomas about artists who have influenced his own approach to the body.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon'sBody of Artand buy the book.

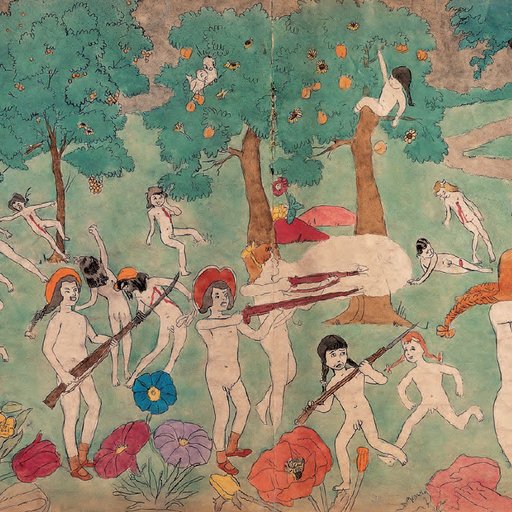

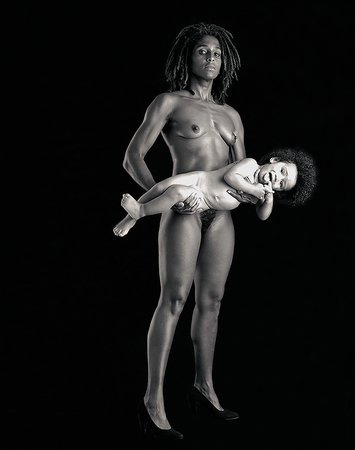

Yo Mama (1993) by Renee Cox

Yo Mama (1993) by Renee Cox

When I think about the body in art, I think about Renee Cox's “Yo Mama” series, which I had on a t-shirt when I was in high school. What she was doing, especially in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, was talking about the black female body as a superhero—an almost bionic, all-powerful body that can take on so many burdens but at the same time be fortified. For me, it was a really different presentation than I was used to. Those images are talking about motherhood through the lens of independence and physical strength.

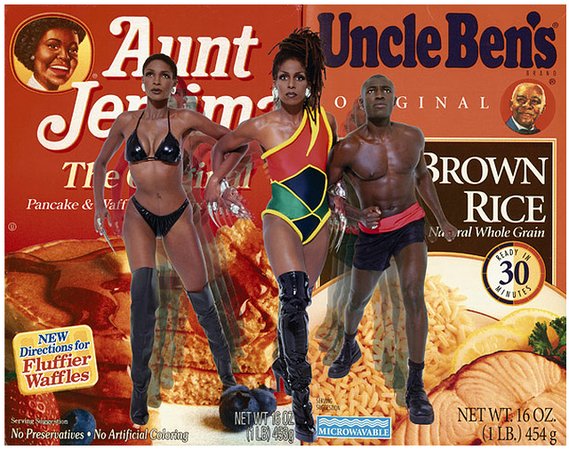

The Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben (1998) by Renee Cox

The Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben (1998) by Renee Cox

On another note, her piece The Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben was definitely a major shift for me in terms of thinking about the opportunities for images in popular culture to be incorporated into critical commentary—something you can definitely see in my work.

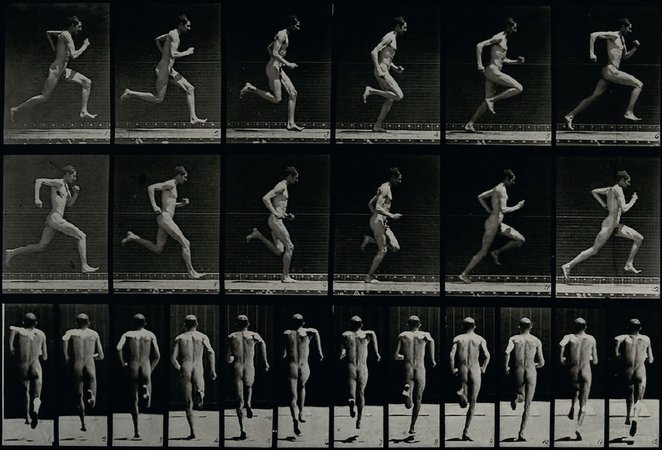

A Man Sprinting (1887) by Eadweard Muybridge

A Man Sprinting (1887) by Eadweard Muybridge

I've always been interested in framing and context, in thinking about how any and every historical moment can be retold by a split-second change in the moment of capture. I think Muybridge’s studies of the body are some of the very first examples of someone bringing awareness to the way in which things that seem fluid are actually connected to a number of other things. Movements are always connected to a combination of gestures, and he was one of the first to show that using photography.

Opportunity (2015) by Hank Willis Thomas

Opportunity (2015) by Hank Willis Thomas

In some of my more recent sculptures, I’ve started taking images from photographs and freezing them to turn them into sculptures. That's definitely a nod to Muybridge—I’m thinking about framing a moment and what that means, but also giving it a different perspective. When a photograph becomes a sculpture, all of a sudden you get to walk around it and interpret it in new ways.

America the Beautiful (1968) by David Hammons

America the Beautiful (1968) by David Hammons

When I saw David Hammons’s body prints, I was really struck by how he could leave an impression on one of the most iconic symbols of "freedom" in my consciousness. He was able to make an indelible mark in my mind by pressing his body on the American flag.

Africa America (2009) by Hank Willis Thomas

Africa America (2009) by Hank Willis Thomas

David Hammons’s work with the American flag started with these prints, but he moved beyond it to make his African American Flag. He made works that are not necessarily about the body, but about the voice. That piece makes me think of works of mine like Black Righteous Space and Africa America, which are really speaking to the conjectural ideas that I think he was trying to evoke with that work.

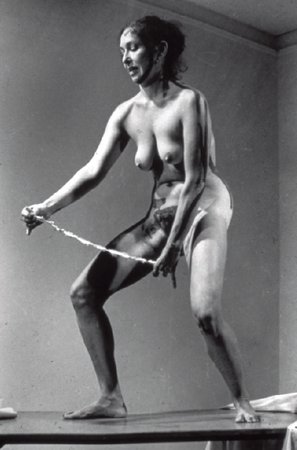

Interior Scroll (1975) by Carolee Schneemann

Interior Scroll (1975) by Carolee Schneemann

Interior Scroll is intense. When I first saw it, I was just scared by the idea that someone would be so bold and also so exposed. With Schneemann's work, I had a major recognition of an artist's capacity to redefine the body and its functionality. Her work talks about the political potential of the body through art. She was dealing with the psychological, the physiological, and the phenomenological—with the truly visceral experience of being a woman in that period of time and the expectations that went with that.

Meat Joy (1964) by Carolee Schneemann

Meat Joy (1964) by Carolee Schneemann

I think Carolee Schneemann, Marina Abramovic, and Joel-Peter Witkin were some of the first artists that actually scared me. They scared me because they were artists who were dealing with blood and dealing with flesh. They frequently did things that I definitely wished would never happen to me and that I definitely also wished that I didn't have to watch happen to another person. That speaks to elements of human life and the human experience that are often avoided. It's really crucial for artists to deal with the things that most of us don't want to have to pay attention to, in order to remind us that when we get lulled into comfort we often stop living.