The Chinese mark New Year this Friday, and it gives us an opportunity to consider how times have changed. Even a brief glance at contemporary Chinese art demonstrates how similar the artist’s experience is becoming in the East and West, and how different they once were. Years ago, the gulf between us was huge. In much of Europe and America, the 1960s are remembered as an era of civil rights, pop art and social permissiveness; in China, it was the time of the Cultural Revolution, and violent upheaval. Today, our worlds are more closely aligned; artists such as

Andy Warhol

and

Gerhard Richter

now exert a profound influence over Chinese painters, while timeless, Chinese artistic techniques, and far more timely aspects of Chinese economic and manufacturing might reminds us of how the Middle Kingdom once lay at the center of global culture, and is beginning to take up that position again.

Ai Weiwei,

Zodiac (from Papercut Portfolio

), 2019

Ai Weiwei,

Zodiac (from Papercut Portfolio

), 2019

Ai Weiwei

’s 2019 papercut makes reference to the Chinese zodiac, but also to the lost zodiac water-clock fountain, created by the Italian Jesuit missionary and artist Giuseppe Castiglione in the grounds of Beijing’s Imperial Summer Palace for the Qianlong Emperor in the late 18th century, and looted by British and French troops in 1860. Not all of the bronze zodiac heads which once adorned the fountain have been recovered, so Ai Weiwei applied a little artistic licence when creating his own version.

This isn’t the artist’s first piece dedicated to this lost treasure; in 2010 he created bronze and gold models of the animal heads. Some of those editions now sell for millions; this paper version is a little more affordable, but still engages with questions pertinent to antique and contemporary Chinese art, such as the notions of authenticity, national pride, relations with the West, as well as myth, master crafts and manufacturing.

Zhang Xiaogang,

Big Family No. 1 (from Bloodline Series)

, 2006

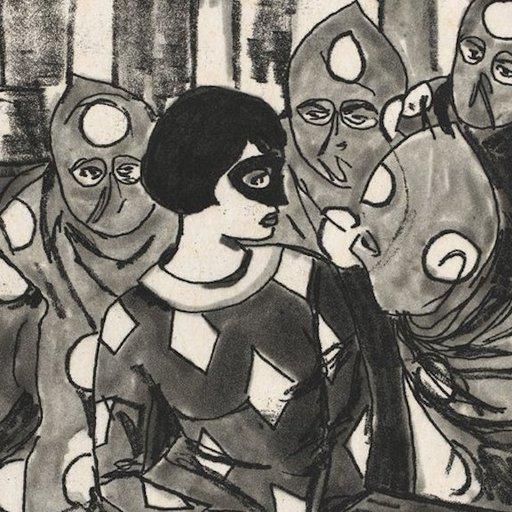

Zhang Xiaogang was born in the Yunnan province in 1958 and grew up during the Cultural Revolution. His parents were taken away for three years of communist 're-education’, and the turbulence of that period has influenced the artist’s work as an adult.

Zhang Xiaogang's Bloodline Series paintings are not only his best-known works; they’re also among the most distinctive pieces in contemporary Chinese art, addressing national concerns about identity and past traumas, while drawing on both domestic figurative traditions of portraiture as well as internationally recognized artistic influences, such as the work of Gehrard Richter. Yet there are personal strains and fissures captured in Zhang Xiaogang's family paintings – not least his mother’s mental health difficulties. “I was very young when I became aware of my mother’s illness,” the artist has said. “She would be fine for days and then change, one minute crying inconsolably, the next laughing hysterically. She attacked people verbally on the street and would go out and get herself lost for days. But then she would be normal again. Although she was always so very nice to me, as a child, I found it terrifying.”

Xiaobai Su,

Big Inkstone 4,

2018

Viewed from a Western perspective, Xiaobai Su ’s Big Inkstone might bring to mind abstract works by Rothko or Richard Serra . So it may come as some surprise to learn that Xiaobai Su began his career as a figurative, social realist painter. Born in 1949 in Wuhan, the artist went on to study at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf – Gerhard Richter’s alma mater – during the late 1980s, during which time the painter developed a greater interest in a painting’s surface.

Xiaobai Su often controls that patina of his abstract works with the use of traditional Chinese lacquer techniques, applying resin, and oil paint onto linen or wood in a contemplative manner. This Big Inkstone piece is formed from photoetching and aquatint on handmade paper, though qualities of antique, Chinese abstraction live on in this piece too; an inkstone is a kind of palette, used for mixing inks, though in this piece, the artist develops this subject in to a crisp work with mystical possibilities.

Sometimes compared to Yves Klein , Warhol and Maurizio Cattelan , Xu Zhen is a provocative contemporary artist, quite willing to lampoon the studio production line – in 2009 he appointed himself as CEO of his own art firm MadeIn Company – as well as China’s place within the world as a source of ancient mysticism and modern manufacturing. All this provocation has proved successful. In 2001, Xu Zhen became the youngest to take part in the Venice Biennale 2001; in 2005 he represented China in Venice; and in 2014 the Armory Show commissioned him to produce a solo exhibition. This is Chinese art made after the Mao era, as the country reaches its economic apex. The Buddha might urge us to forego worldly possessions but this technicolor one is very much for sale.

Yun-Fei Ji,

The Three Gorges Dam Migration

, 2009

Yun-Fei Ji,

The Three Gorges Dam Migration

, 2009

How should you best negotiate the lay of the land in modern China? Perhaps via Yun-Fei Ji ’s beautifully detailed work. “I use landscape painting to explore the utopian dreams of Chinese history, from past collectivization to new consumerism," explains the Chinese-born, US based painter. Another contemporary artist whose formative years coincided with the cultural revolution, Yun-Fei Ji trained in classical, Chinese techniques, producing works of ink on paper.

He came to the US in 1986 on a Fulbright Fellowship, yet he continues to draw on his homeland for inspiration. This particular piece examines the Three Gorges Dam, a huge hydroelectric project in Hubei province, central China, which has enabled the country to cut its carbon emissions, while flooding villages and displacing much of the region’s local population. US photographer Edward Burtynsky has tackled the same subject, yet no one expresses quite the same level of local lyricism as this artist.

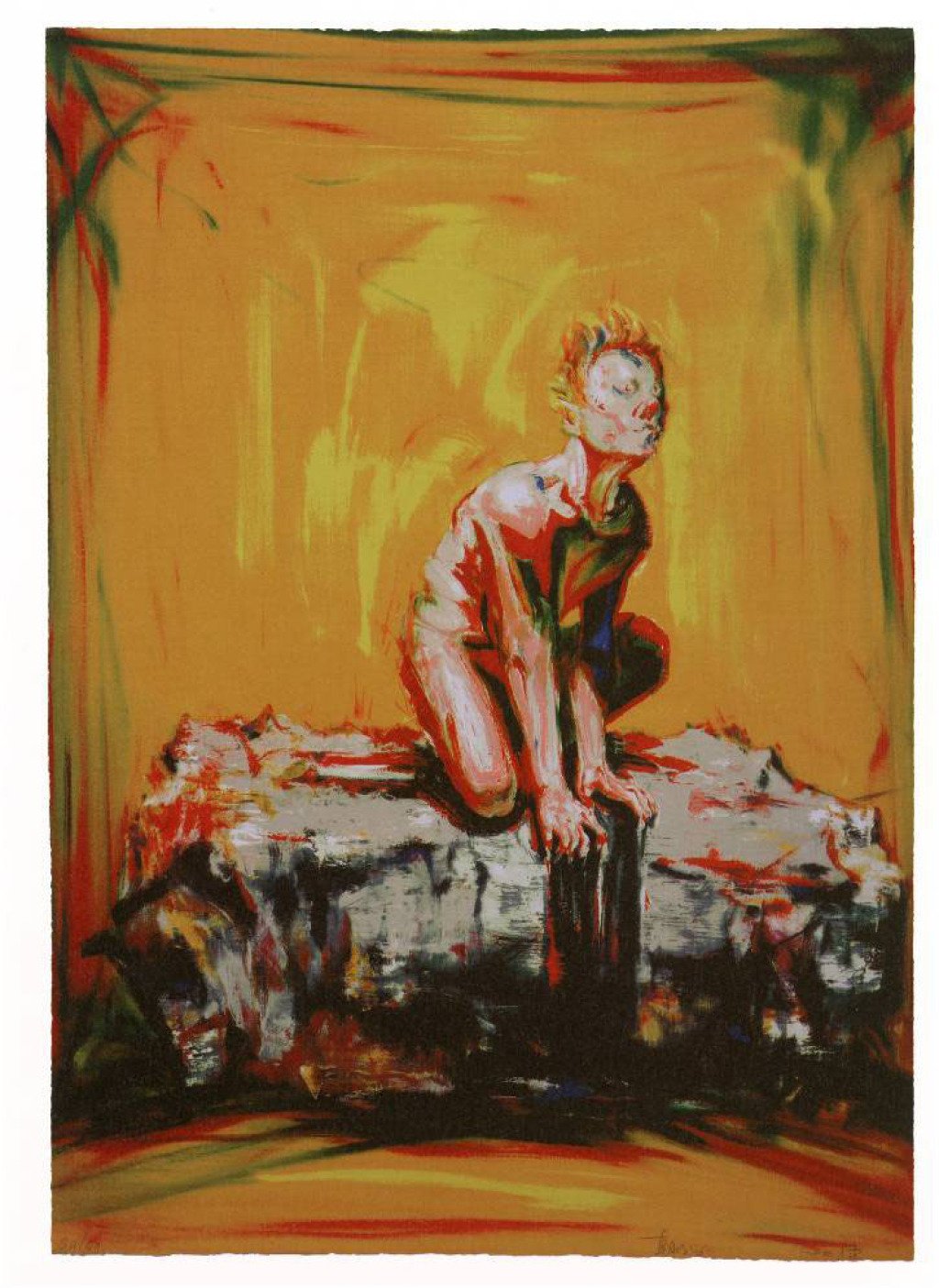

Self reflection and the inner, emotional life weren’t primary concerns in Chinese art during Mao’s rule in China. Yin Zhaoyang , however, was born in 1970, just six years prior to Mao’s death, and developed his artistic sensibilities alongside a generation of fellow painters more deeply concerned with the human condition. A Western viewer might think of Bacon or Freud when viewing this evocative, figurative work, given its fleshy tones and box-like background. However, the artist’s own influences go back quite a bit further. The print forms part of Yin Zhaoyang’s Mythology, which draws on both ancient myths and contemporary concerns about the human condition within society.

If you'd like to find out more about Chinese art take a look at Phaidon's The Chinese Art Book which features 300 works from the earliest dynasties to the new generation of contemporary artists enlivening the global art world today. If you're interested in buying the works above and below, simply click on the picture.