Literature is full of maternal archetypes. The Good Mother: Mrs. March in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women . The Bad Mother: Madame Merle in Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady . The Mad Mother: Margaret “Dirty Pillows” White in Stephen King’s Carrie . Shakespeare’s Hamlet gives us Gertrude, an embodiment of the sexy mommy who stirs up her son’s oedipal longings; while in Pride and Prejudice , Jane Austen creates an embarrassing mom for the ages in the figure of Mrs. Bennet.

And yet, as the novelist Margaret Atwood points out, such archetypes seldom if ever reflect the complexities of real women, who cannot simply be reduced to their maternal role: “What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves - our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies”.

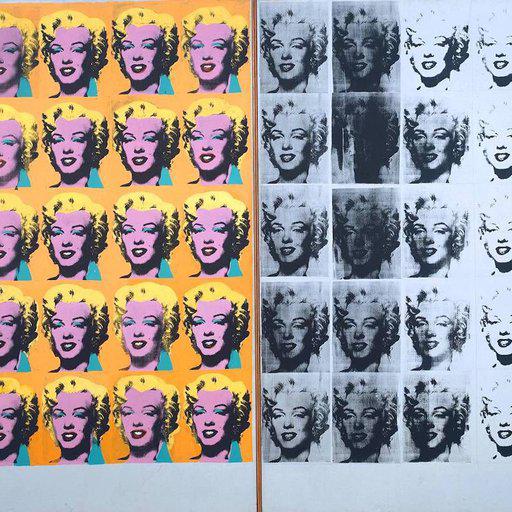

Art history has its own deep archive of images of motherhood, in which maternal archetypes are both reinforced and subverted. Many of these are representations of Mary, the Christian Mother of God, the finest examples of which surely include Duccio’s Maestà (1300), Raphael’s Alba Madonna (c.1510) and Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin of the Rocks (1483-6). Against such idealized visions we might set the earthier fare of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s painting of his own aged mother, Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 (1871), Dorothea Lange’s celebrated photograph Migrant Mother (1936), and the conceptual artist Mary Kelly’s ground-breaking project Post-Partum Document (1973-79), which included a display of her baby son’s dirty nappies, preserved for posterity.

For this edition of Group Show, we bring together six works by contemporary artists that take mothers as their subject. Here, the maternal figure is presented as a source of refuge and nourishment, but also of unbearable pain. She is at once an ancient goddess and a youthful icon, an image from a dream and from a nightmare. While the world’s mothers are often taken for granted, these works place them firmly centre stage.

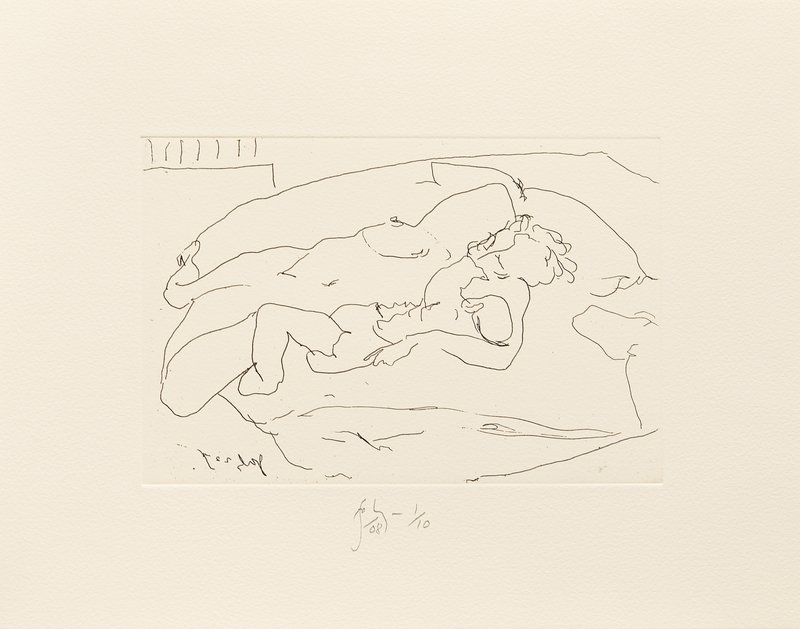

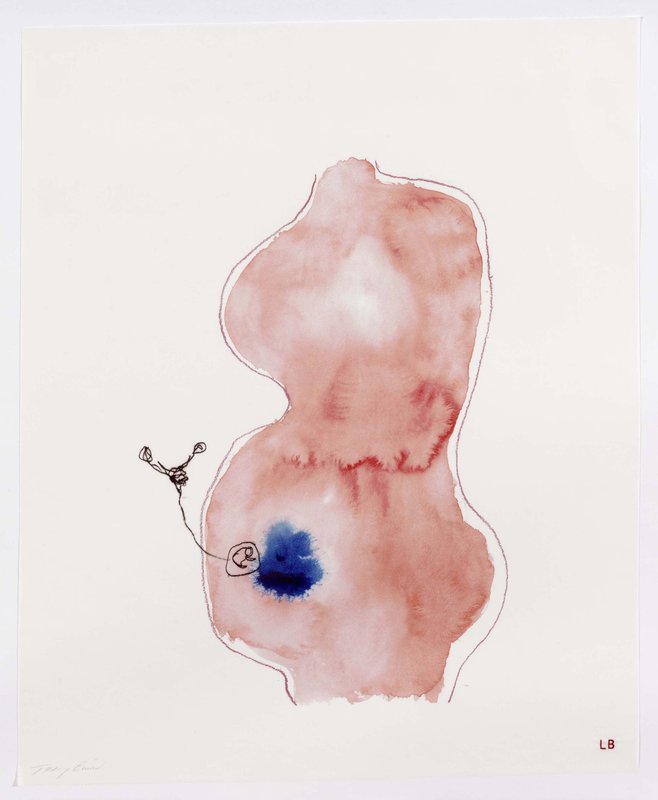

Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin - Do Not Abandon me #11: Looking for the Mother (2009-10)

This collaboration between Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin seems like it was written in the stars. Not only do both their oeuvres approach gender, sexuality and the body with an unflinching frankness, there’s also the fact that the British Turner Prize nominee cited the legendary French artist as a mother figure in her 2005 fabric work The Older Woman, which bears the inscription “I think my Dad should have gone out with someone older like Louise, Louise Bourgeois”. Four years later, the two women began working together on Do Not Abandon Me (2009-10), a suite of prints for which Bourgeois provided washy male and female silhouettes, passing these images on to Emin who overlaid them with drawn images and text – an experience she likened to “touching a piece of history”.

In Do Not Abandon me: #11: Looking for the Mother, Bourgeois depicts a pregnant female torso in profile, reducing this body to a fleshy bag of vital, life-supporting organs. On its belly blossoms a splotch of dark blue pigment, and near this Emin has drawn a foetus, attached by a lolling cord to a pair of exterior ovaries. Is this tiny proto-infant in search of a mom, as the work’s title suggests, and if so is Bourgeois’ anonymous torso – absent not only limbs, but also a face and brain – the maternal figure it seeks? Perhaps that blue, womb-like splotch was a place the foetus once called home. Might it, against all physiological precedent, do so once again?

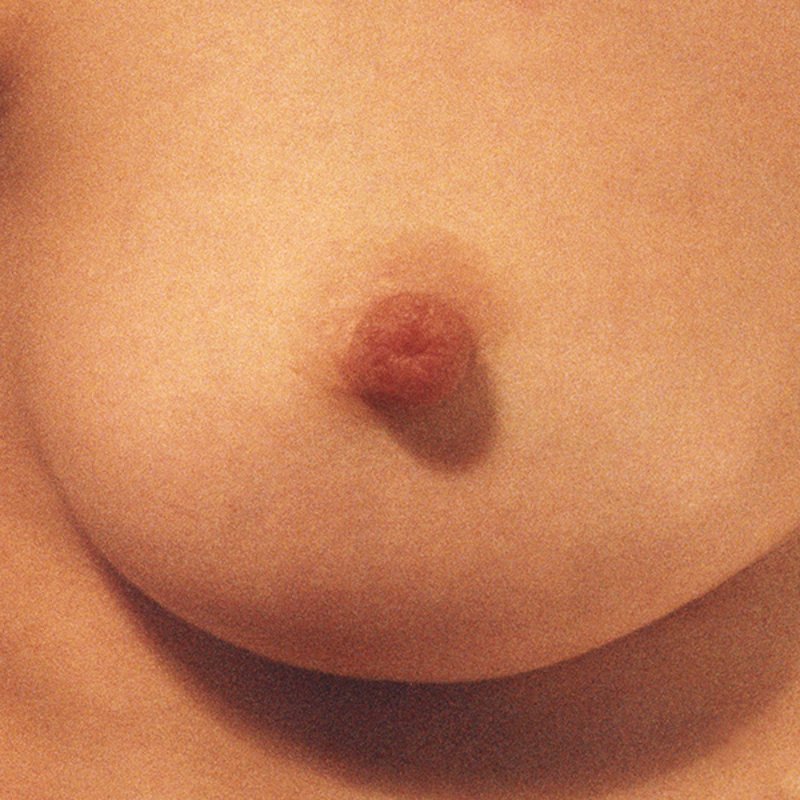

Yoko Ono - My Mommy is Beautiful (1997/2018)

The approach of the pioneering Japanese conceptual and performance artist Yoko Ono to her practice is best summed up in her own words: “I thought art was a verb, not a noun”. While she came to global fame through her marriage to the late John Lennon, Ono’s lasting legacy is her contribution to widening debates around what an artwork might be, which began with her early association with avant-garde figures such as La Monte Young and John Cage, and continues to this day. Embracing experimentation at every turn, she is living proof of her own dictum: “You change the world by being yourself”.

In this photographic print, My Mommy is Beautiful , Ono focuses on a single female breast, which appears to be presented not as object of erotic fascination, but as a wellspring of nourishment. So closely cropped is this image that we might imagine ourselves as infants nuzzling at the nipple – a formative experience for almost every human being on Earth. And yet, this reading of the work is complicated by its pendant piece, also titled My Mommy is Beautiful , which offers up an image of a woman’s pudenda, covered with a light furze of strawberry blonde pubic hair. With characteristic clarity, Ono frames a complicated truth: whatever our gender or sexual orientation, our attitude to our own bodies, and those of others, will always be inflected by our early proximity to our mother’s corporeal form. Hers, after all, is the body that gave us life, and the body that as infants we had to learn – in a painful liberation – to distinguish from our own.

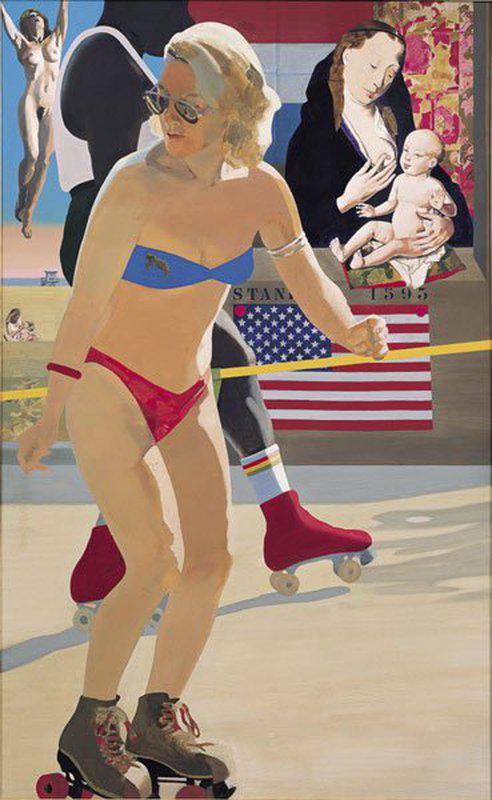

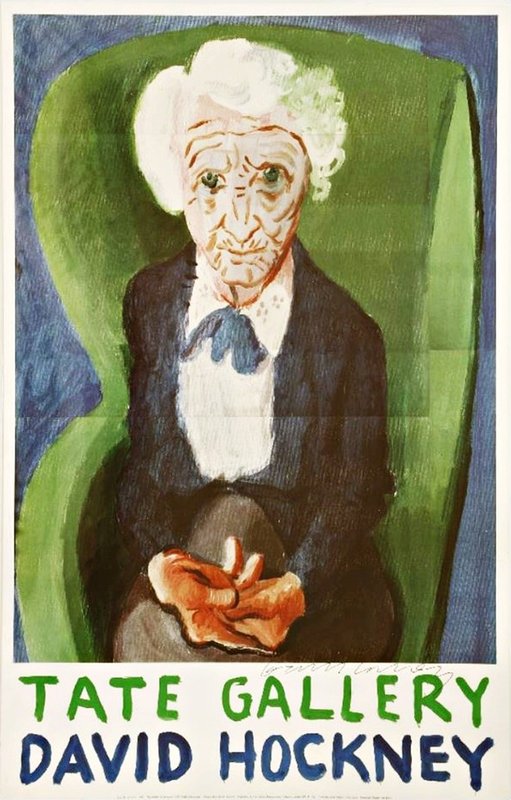

Peter Blake - Madonna on Venice Beach (1996)

Picture Los Angeles’ Venice Beach and what comes to mind? Ageing hippies and pumped-up body builders, the Z-Boy skateboarders and palm-fringed canals. Then there’s the neighbourhood’s famous boardwalk, where street performers and homeless junkies tout for change, while the endless Pacific ocean roars and glitters in the distance. Venice Beach’s sunny, freewheeling and seedily glamorous vibe is a million miles away from the sombre religiosity of the 15th Century Low Countries, making it all the more surprising that this print by the seminal British Pop artist Peter Blake features an image of the Netherlandish painter Dirk Bouts’ masterpiece The Virgin and Child (1465), which appears to have been pasted to the wall like an ad for surf wax, or Bud beer. What to make of this juxtaposition?

Perhaps the answer lies in Blake’s title, Madonna on Venice Beach , which refers both to Bouts’ Mary and to the blonde, bikini-wearing roller skater whizzing through the foreground of the work, who bears a strong resemblance not to the Biblical Madonna, but the late 20th century’s most famous Material Girl, Madonna Louise Ciccone. By invoking this pop cultural icon (who in 1996, the date of this work, gave birth to her first child, Lourdes), Blake gives us a Holy Mother for our times – dynamic instead of passive, no longer modest but rather unapologetically proud. Unlike Bout’s Virgin, she feels, as the superstar singer put it, “all shiny and new”.

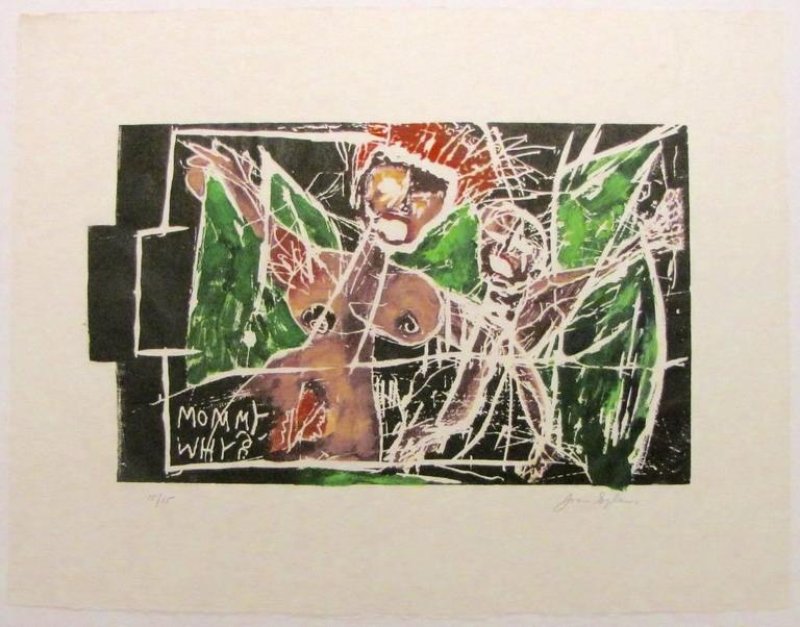

Joan Snyder - Mommy Why? (1983)

The acclaimed American artist (and MacArthur “Genius Grant” awardee) Joan Synder first came to public attention in 1970s New York, where her elegant, gestural “stroke paintings” reframed the macho, bombastic discourse of Abstract Expressionism through a feminine – and feminist – sensibility. In the years that followed text, symbols and wound-like openings began to appear in her wildly improvisatory, often wrenchingly personal canvases, alongside such unexpected materials as ribbons, glitter, and coloured beads. Highly influential on younger generations of artists, Snyder’s work combines a complex, visually arresting materiality with an often rawly confessional tone. As she has said: “In spite of some who might not think my work beautiful, I almost always try to make beautiful paintings. I think being vulnerable, however complicated and difficult it may be, is a form of beauty.”

In Snyder’s woodcut Mommy Why? we’re confronted with the image of a naked, flame-haired woman, her eyes and mouth blazing white-hot with anger, her breasts and vulva rendered in savage, slashing strokes. Her right arm arcs down, as though she has just slapped the child that stands beside her, whose body appears all but obliviated by this sudden maternal violence. The work’s title is incised into its bottom left corner, and at first glance it seems obvious that it’s the kid, here, who begs “MOMMY WHY?”. But could it be that it’s the mother who poses this question? Might her own mom have set this cycle of abuse in motion, and if so when will it ever stop?

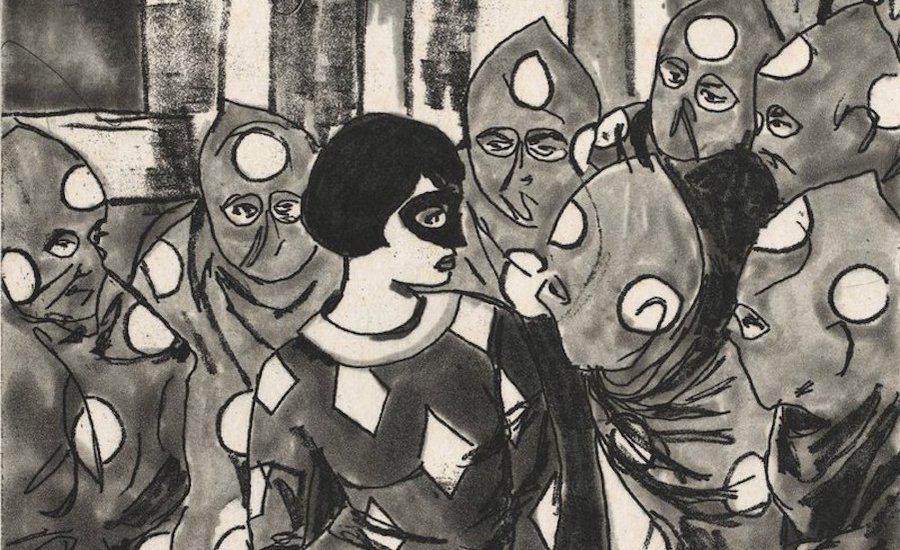

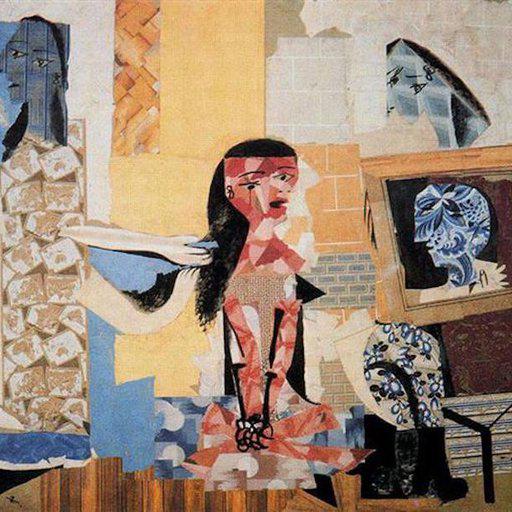

Marcel Dzama - A Mother of the Seven Sons (2015)

The most prolific mother in recorded history is the wife of the 18th century Russian peasant Feodor Vassilyev, who gave birth to 16 pairs of twins, seven sets of triplets and four sets of quadruplets – a total of 69 babies, only two of whom failed to survive infancy. An astonishing feat, by any measure, although apparently not so astonishing that the Tsarist authorities thought it worth noting down Mrs. Vassilyev’s first name. In comparison, the woman in the lauded Canadian artist Marcel Dzama’s A Mother of the Seven Sons appears positively sluggish. Indeed, the more we look at this etching, the less likely it feels that the hooded figures who surround her are her children, at least in the biological sense.

One clue is her age: she is far too youthful to have borne seven adult offspring, even if they are septuplets, as their identical spotted costumes suggest. Another is Dzama’s title: she is “A Mother to” these men, not “The Mother of” them, a hint perhaps that this is a professional role, like a matron in a hospital, or a mother superior in an order of nuns, rather than an index of parenthood. In any event, this woman – part circus performer, part superhero – has a lot on her hands, with her “sons” crowding in on her, and taking her to task for some unknown apparent wrongdoing. We might wonder if this is nothing but a strange, unsettling dream experienced by a pregnant mom-to-be, on whom an ancient truth is suddenly dawning: being a mother is the hardest job in the world.

Mamma Andersson - Mother’s Day (2013)

Since the first flowerings of human spirituality up until the spread of the Abrahamic religions, the figure of the mother goddess – who often also served as the goddess of fertility, harvests, and of the Earth itself – has been near-universally venerated. Commonly paired with a sky father god, she has had many guises, from the Greek Hera to the Hindu Parvati, from the Norse Fjörgyn to the Chinese Hòutǔ, from the Celtic Danu to the Maori Papatūānuku. While each of these deities developed out of a particular set of geographic, cultural, and socio-economic circumstances, and while they have many marked differences, taken as a whole they point to a deep recognition that motherhood is at the centre of our species’ life.

In the celebrated Swedish artist Karin “Mamma” Andersson ’s print Mother’s Day, we are presented with what at first site appears to be a shrine to a maternal goddess, in a dusty, tree-shaded spot somewhere in the Graeco-Roman world. There is little, here, to tell us whether the artist has set her scene in Classical antiquity or the present day, and it is this temporal question that lies at the heart of the work. Is this a place where devotees offer up prayers to Juno, wife of mighty Jupiter, or is it somewhere tourists snap selfies next to yet another timeworn statue of a long-neglected deity, before heading off for a slice of pizza and a Coca-Cola Lite? Perhaps the answer is in the fallen plinth that lays beside the stone goddess. Here at least, the day of the mother goddess – if not the mother – seems to be long passed.