While white is often used as a muted backdrop against which noisier shades announce themselves - not least in the “white cube” of the gallery space - it is very far from neutral. “White” wrote G.K. Chesterton “is not the mere absence of colour; it is a shining and affirmative thing, as fierce as red, as definite as black. God paints in many colours; but He never paints so gorgeously, I had almost said as gaudily, as when He paints in white”. The English novelist had a point. Consider, to take just one example, its use in ritual clothing, which spans christening gowns, wedding dresses, and burial shrouds. White marks milestones in our lives, from the cradle to the grave.

Given white’s rich store of cultural associations – among them not only holiness, healing and hygiene, but also erasure, death and new beginnings – it’s little wonder it has been deployed by some of history’s greatest artists to startling effect. Think of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s extraordinary wintry landscape Hunters in the Snow (1565), or James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s shimmering portrait Symphony in White, No.1: The White Girl (1861-2), or indeed of the palely hooded Klansmen that stalk, like all-too-solid ghosts, through the paintings of Philip Guston . Then there is the Modernist sub-genre of the white monochrome, which began with Kazimir Malevich’s abstract canvas White on White (1918), and was subsequently taken up by such signal figures as Robert Ryman , Piero Manzoni and Agnes Martin .

Here, we bring together works by six contemporary artists that explore this (non) colour. For them, white speaks of withholding information, and the wonder and terror of the tabula rasa, of the legacies of structural racism, and of the deadly beauty of snow. Pale and interesting? That’s a serious understatement. These works are white hot.

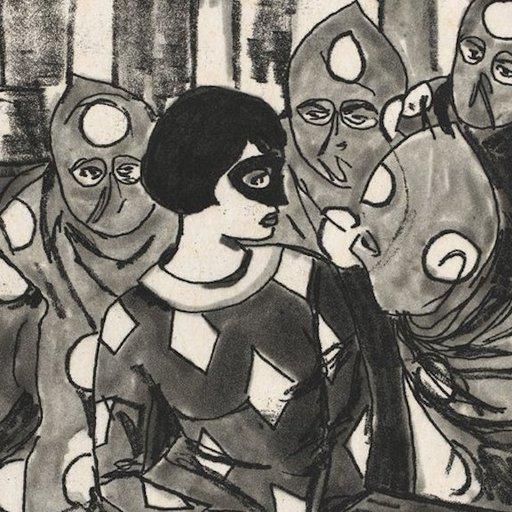

JOHN BALDESSARI - Crowds with Shape of Reason Missing: Example 6 (2012)

One of the most influential artists of his generation,

John Baldessari

systematically stress-tested the boundaries of what might be considered art. Whether incinerating a decade’s worth of his own paintings (The Cremation Project, 1970) or documenting himself waving at far-off ships (Goodbye to Boats, 1972-3), taking to the fairway for an absurdist game of pitch and putt (The Artist Hitting Various Objects With a Golf Club, 1972-3) or covering the faces of people depicted in found photos and film stills with his signature dots (Bloody Sunday, 1987), the pioneering Los Angeles Conceptualist created a body of work that was at once uncompromising, intellectually rigorous, and laced with playful humour. Throughout his long career he stayed true to the title of an instruction piece he formulated in 1971: I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art.

One of the most influential artists of his generation,

John Baldessari

systematically stress-tested the boundaries of what might be considered art. Whether incinerating a decade’s worth of his own paintings (The Cremation Project, 1970) or documenting himself waving at far-off ships (Goodbye to Boats, 1972-3), taking to the fairway for an absurdist game of pitch and putt (The Artist Hitting Various Objects With a Golf Club, 1972-3) or covering the faces of people depicted in found photos and film stills with his signature dots (Bloody Sunday, 1987), the pioneering Los Angeles Conceptualist created a body of work that was at once uncompromising, intellectually rigorous, and laced with playful humour. Throughout his long career he stayed true to the title of an instruction piece he formulated in 1971: I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art.

For his print Crowds with Shape of Reason Missing: Example 6, Baldessari took a found still from an old sword and sandals movie, and obscured the right-hand portion of the image with a blobby massing of white pigment. To the left, we see a crowd of townsfolk peering eagerly over the shoulders of a phalanx of helmeted Hoplites, but – frustratingly – we have no way of knowing what they’re peering at. The arrival of a hero, a villain, a dazzling Classical beauty, played by some unknown matinee idol? Whatever is it, Baldessari’s act of redaction draws our eye back, unremittingly and contra all our established visual habits, to the mass of spectators. Speaking about the making of this work, the artist said that “I like the idea that crowds have a certain shape”. The process of whiting-out information, here, both conceals and reveals. With the movie’s star out of the picture, it is the extras who shuffle, blinking, into the spotlight of our gaze.

ANGELA DE LA CRUZ - White (Nothing) Print (2010)

In his Lectures on Literature, the Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov related his excitement during the moment that precedes literary creation: “the pages are still blank, but there is a miraculous feeling of the words being there, written in invisible ink and clamouring to become visible”. This is easy enough to say if one is the prolific author of such acknowledged stone-cold classics as Lolita and Pale Fire, but what about those of us for whom the untouched Word document – or indeed canvas – is so often not a tabula rasa pregnant with possibilities, but rather a chilly white expanse, as treacherous and inhospitable as the Siberian tundra?

The British Turner Prize-nominee

Angela de la Cruz’

s work White (Nothing) Print depicts that all-too-common sight in the frustrated writer or artist’s workspace: the balled-up piece of paper, tossed aside because the words or images on its surface fell woefully short of expectations, or indeed never emerged at all. Is this evidence that de la Cruz’s creative motor has suffered a malfunction, or (perhaps even worse) that she’s crashed into a block? If so, the artist has managed to salvaged something from the wreckage: that crumpled piece of white A4 has become the subject of a still-life, and the road ahead is once again clear.

DREAD SCOTT - Post-White (2013)

The term “Post-Black art” was coined in the late 1990s by the Black American curator Thelma Golden, to define the work of a generation of then-emerging young Black American artists, among them Julie Mehretu, Mark Bradford and Rashid Johnson. Unpacking this concept in an essay that accompanied her seminal 2001 group exhibition “Freestyle” at The Studio Museum, Harlem, Golden wrote that it encompassed practitioners “who are adamant about not being labelled ‘Black’ artists, though their work [is] steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of Blackness […] They are both post-Basquiat and post-Biggie”. While Golden’s show was widely understood as an attempt to correct the historical marginalization of Black art, it was not without its detractors. As the legendary Black American artist David Hammons put it: “racism is real, and many artists who have endured its effects feel the museum is promoting a kind of art – trendy, postmodern, blandly international – that has turned the institution into a ‘boutique’ or ‘country club’”.

Bearing the words “POST-WHITE” in white pigment on an all-white ground, this print by the acclaimed Black American artist Dread Scott might be interpreted as a response to the (still ongoing) debate triggered by “Freestyle”. In one sense, it is a witty play on the genealogy of the pale 20th century monochrome canvas – the most famous examples of which were, we should note, all painted by white artists. Beyond this, however, it poses an urgent question: why is it that Black artists and curators must continually interrogate – and contest – the Blackness of Black art, while the whiteness of white art is barely if ever made visible?

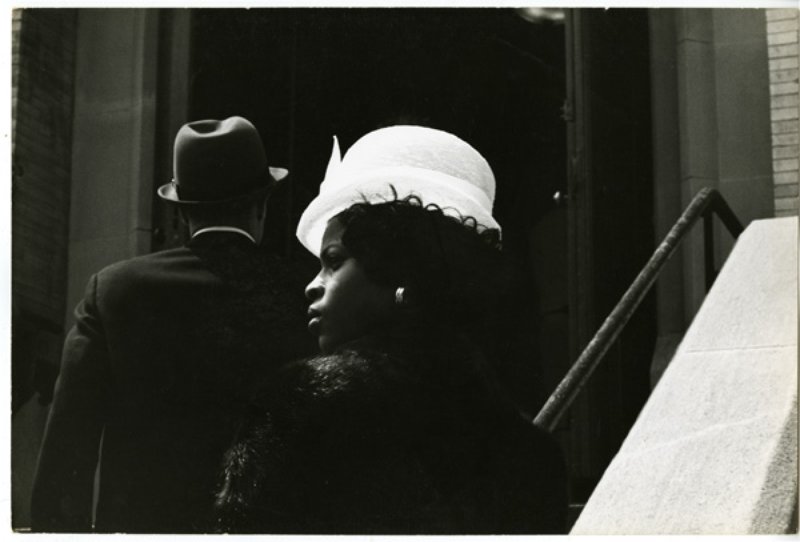

JAN YOORS - Untitled (Wedding in Harlem – Hat) (1962)

The origin of the Western “white wedding” does not, as is commonly supposed, lie in that colour’s long-standing connotations of purity and virginal virtue. For many centuries, brides dressed in whatever color took their fancy, and it was only following the marriage of Queen Victoria to Prince Albert in 1840 – for which the young British monarch wore a white Honiton lace gown, receiving rapturous coverage in the burgeoning print media – that the trend took hold among the wealthy elite, eventually filtering through to the rest of society, and becoming cemented as ‘tradition’. To any contemporary bride-to-be who bemoans the white wedding dress’s stain-attracting impracticality, its dubious sexual politics, and its resemblance to a meringue, this piece of revisionist history trivia must come as a relief.

In the celebrated Flemish-American artist, photographer, writer and filmmaker Jan Yoors ’ shot Untitled (Wedding in Harlem – Hat), we encounter a young Black bride on a New York street, about to walk up the steps of a church to pledge her troth to her beloved. It’s a cold day, so her dress is hidden by a dark fur coat, but her white hat blazes like a beacon, not so much a thing of milliner’s fabric as a gleaming crown, or even a halo. What thoughts whir beneath this headgear? Perhaps the direction of her gaze is one clue. She does not look forward, towards the church steps, but over her shoulder, back at the life – and the self – she is about to leave behind.

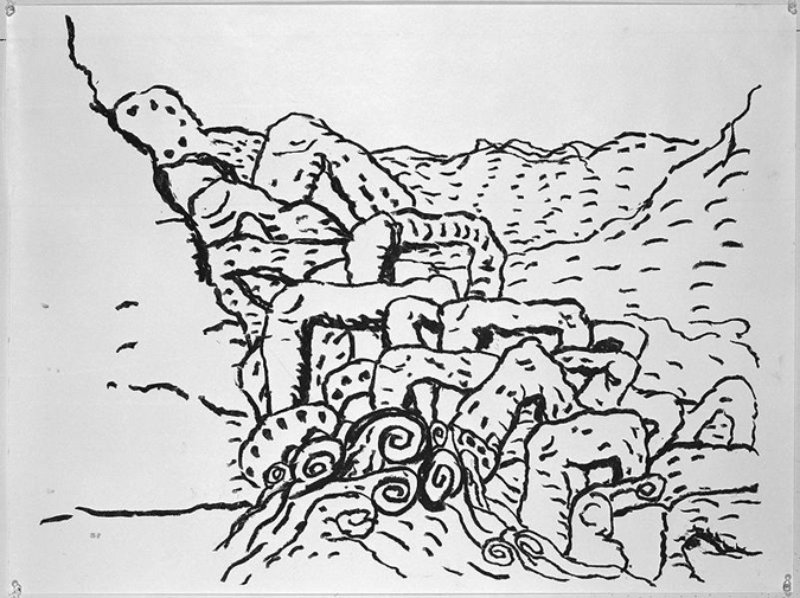

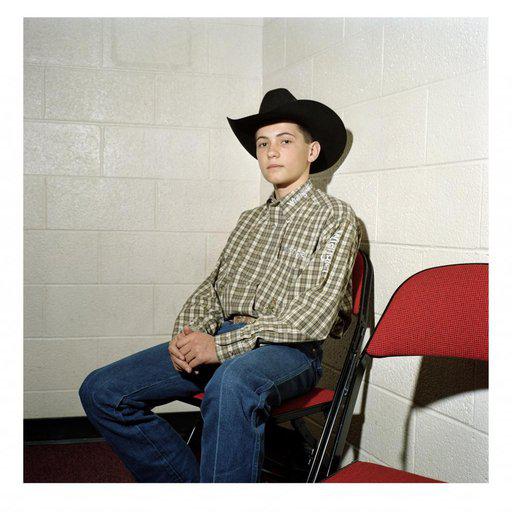

THOMAS BANGSTED - Collapsed Barn (2006)

Literature contains few passages as melancholy – and as beautiful – as the closing lines of James Joyce’s short story The Dead (1914), which describes its protagonist, Gabriel Conroy, witnessing snow blanketing an Irish churchyard: “It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead”. Here, a meteorological event betokens not only the inevitable erasure of individual human lives, but also of their memory. Heartbreakingly, Joyce is aware that even the words of his own story will – like the ‘headstones’ and ‘barren thorns’ he writes of – be whited-out by inexorable time.

In the noted Danish-born, New York-based artist Thomas Bangsted ’s photograph Collapsed Barn, we see a farmstead submerged in heavy snow, beneath a clear blue sky. So destructive has this flurry of weather proved that the farm’s structures have buckled and collapsed, their beams and girders poking from the white drifts like the remains of an ancient temple unearthed during an archaeological dig, or abstract sculptures fashioned by some unknown land artist. There’s an echo, here, of the German Romantic painter Casper David Friedrich’s canvas The Sea of Ice (1823-24), which depicts the wreck of a ship in the icy Arctic. Like Joyce’s The Dead, Bangsted’s shot is a work about entropy, in which life fades not to black, but to brilliant, unremitting white.

MAX BILL - Composition w/ White Center (Geometric Abstraction) (1972)

Widely considered the single most influential figure on 20th century Swiss design, Max Bill – who studied at the Dessau Bauhaus under the artists Josef Albers , Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee – left a legacy that spans architecture, art, theoretical writings, pedagogy, and graphic and product design, not least his much imitated iconic timepiece for the German watch manufacturer Junghans, which still graces discerning wrists today. While his spare geometric paintings and sculptures have led some commentators to identify him as a formalist, the truth is more complex. For Bill, the purpose of his work was to transcend “surface values”, and embody not only “form as beauty, but also form in which intuitions or ideas or conjectures have taken visible substance”.

As its title suggests, Bill’s print Composition w/ White Center (Geometric Abstraction) is an arrangement of coloured triangles and rectangles, in the middle of which sits a white square. For all this work’s apparent rationalism – and for all that Bill once wrote “I am of the opinion that it is possible to develop an art largely on the basis of mathematical thinking” – there is something mandala-like about the way its geometrical forms converge on the emptiness of its central motif. Pursue this thought, and we might interpret the print as a map of the cosmos, of the type we see in Tibetan Buddhist thangka paintings. White light, we should remember, contains all other colours. Are Bill’s red, yellow, blue, green and black Euclidean figures about to merge into – or be obliterated by – a higher plane of reality?