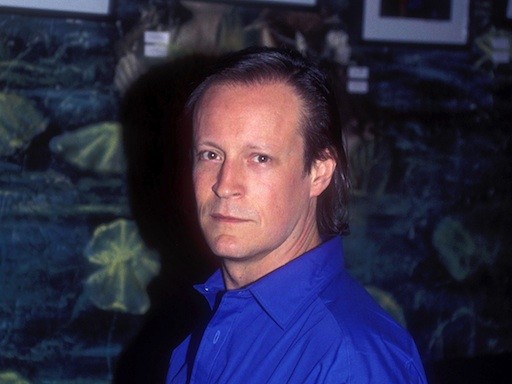

Known for his improbably elegant sculptures and installations crafted from half-empty plastic bottles, discarded shipping crates, and other everyday detritus, the artist Tony Feher has for years staked his flag in an embracive notion of beauty that eludes easy categorization. To mark the release of a new print created with Feher—who currently has a solo show at the Des Moines Art Center—Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the artist about the ideas behind his work, his method in choosing his materials, and why he objects to being called a poet.

These prints are an edition you made with Artspace that are derived from an exhibition you had in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 2011, where you covered the windows of an old, colonial-era building with blue tape. Can you talk about that installation a bit?

It was a textbook case of a Tony Feher where-would-you-use-blue-tape environment. It was a way of capturing and co-opting the architecture and making it part of the experience, so it wasn't simply about being in a room and looking at a work of art but placing the viewer within a work of art, with the architecture subsumed by the artwork. That's what I'm going for with these architecturally significant, site-determined pieces that I do. I look for the "trick," as I say: What's the trick in this building, this space, this courtyard? What's the thing that's just dangling there for me to catch onto that will let me own the whole thing? I think of it that way. Then this show took an enormous amount of work, and it was up for such a short amount of time—maybe six weeks—and then it was all gone.

This blue tape has become one of your signature materials. What kind of tape is it?

It's painter's tape. Somewhere along the line it came into my life, probably due to a job somewhere. I noticed it was translucent—I was probably masking off a window—and then I noticed that when you overlap strips of the tape it changes the color. And I have a fascination with consumer products that contain within them both physics and philosophy. There's no such thing as a straight line—that's a human construct, and we have put it to great use, but it doesn't really exist. There are no straight lines in nature, unless maybe when you get to the molecular level and you're looking at how molecules bond together. When you get to biology, it's all lumpy and gooey and amorphous. But when you get to the edge of a piece of tape, you can't make a straighter line than that, and that results from a manufactured process on a spinning lathe with super-sharp knives that come down and, voila, you've got this fake edge that demonstrates the line better than anything. And then when you tear the piece off you've got the ragged edge, and all of a sudden you've got the tension between the molecular-level perfect and the biological ragged edge—it's at that juncture that it all came together for me.

It's interesting that you can speak so extensively about the tape without mentioning its blue color, which is something of a motif in your work.

Well, we'll get to that. [laughs] The thing about the color is that the color's a given, and there's nothing that I can do about that. And, hey, people like blue. But so much of what I do—and this might shatter people's illusions, I don't know—is very circumstantial. It's taking advantage of things I come upon and deciding which ones have characteristics or traits that I like or somehow move me or have something that I can exploit and extrapolate from its context. So I'm open to anything, and when something comes along and it's blue, then it's blue.

You mentioned the ephemerality of your work before, and what's interesting to me is that so many of the materials you work with—like plastic drinking straws, styrofoam crates, cardboard boxes, plastic bottles, lightbulbs—are not only disposable but meant to be disposed of after using them. What draws you to these materials?

There's a multiple-part answer. The fact that they are discardable means that they appear in our lives with a certain frequency. Also, I'm a bit of a packrat, and I tend to save things, so accumulations naturally tend to happen. With the things that are meant to be thrown away, I simply don't get to throwing them away on any regular basis, so they begin to stack up, and that gives me an opportunity to look at them and think about their potential. So a lot of it is taking advantage of anything that is at arm's reach. But it also brings something more to the conversation about disposability in a consumer culture, and since the consumer is a human being the conversation begins to speak about a kind of vulnerability and the human experience. So when you look at the metaphor of taking the foam flip container that some burger comes in and tossing it away, well, we toss people away too with the same offhanded gesture. The person is in the middle ther—an empty cup implies a person. And you can deconstruct a stack of coffee cups in many different ways: it can speak about architecture, and it can speak about people.

You've often spoken about being influenced by archeology, and it's interesting that so much of the archeological record comes from "disposable" objects-pottery, buttons, arrowheads, et cetera.

Yeah, absolutely. Isn't that great? It's the garbage dump that tells us who our ancestors were. The ancestors are long dead and most of the objects they held as precious are gone—they get burned up in a fire, they get moth-eaten, they rot away—so it's the hard leftovers that remain. What you are left with are buttons and pots and pipes and just stuff.

Now, it's interesting that these are prints, since I believe that is a new medium for you. Have you ever made prints before?

Never. People have invited me to make prints for many years, and it simply didn't seem to make any sense because I didn't really need the interface of the print to do what I do. There was a disconnect. But when I was photographing some details of this particular body of work, an exhibition I had in Oaxaca, it seemed to me that this was the beginning of a medium where I can see an interface that makes sense to take it to another place. I made the piece, I photographed the piece, and so I was connected to it through the chain. Then I specified that it be printed on an x-size piece of paper and that they saturate the hell out of it by using lots of ink. And it came out well—I'm quite pleased with it. It's an inkjet print with archival ink, but it's not a photographic reproduction, so it actually is a print. But it's not a print in that I cut a plate or carved something, so I like that at the same time it's mine it stays one step away from my hand—the only time my hand was involved was when I was making the actual work from which this detail is derived.

The other works you have on Artspace are not prints but works on paper. Can you talk about them a little? How were they made?

These come from taking a cardboard box from a consumer product and picking it open at the seams and flattening it out. I started doing that obsessively some night, probably stoned, and I thought, "Hmm, that's a very interesting shape." It looked a bit like a flayed skin, like a bearskin rug or something. So I started picking apart all kinds of boxes and trying to predict ahead of time what way it was going to unfold. Then I got all politically upset about something in 2003, when the Anglican Church in Massachusetts elected an openly gay bishop and it caused a huge split, with half of the Anglican convention split because they couldn't put up with it. My feeling was, "Come on, gay guy, why do you want to be part of this club that doesn't want you in it and denies your very existence according to the pages of the thing that you're carrying around?" So I thought about how I could do something to satisfy my sense of outrage, and I made this special mixture of pink glitter to get this really gay color and encrusted some of the boxes. So I've made these different pieces, with one of them called The Bishop's Boyfriend, and one of them called Gay Bishop My Ass, and I thought that the technique of the glitter was really interesting, with the crunchy surface sparkling like a precious jewel. It provided me with a new texture. So that's where the glitter came in, and I've been working with many different colors and also expanding my reach with various boxes. These Bruts are made from boxes of Veuve Cliquot, which is the champagne I drink, so they're pretty big. And if you drink enough champagne you'll turn into a brute. The other ones are the side of your hand.

An interesting aspect to your work is that, to the naked eye, there's very little specialized skill involved.

Well, as soon as you do that it becomes something else. There are, of course, people out there who don't get what I do, or just don't like it. And one of the complaints is that I don't do anything. Well, I'm the hardest-working do-nothing around if that's the case. There's an old Minimalist trope: it's very difficult to do less. It's easy to put on a three-ring circus; it's very difficult to be Martha Graham onstage. So this idea of reducing and reducing and reducing something to find its essence is difficult, and some people get it and some people don't.

Your work is often called poetic. I wonder, what do you make of that description?

Well, I like to be called an artist, so when somebody calls me a poet I say, "I guess they don't quite get that yet." It seems to me that being a poet is something that speaks to a very special kind of perception in life, and I'm a little humbled by it, you know. At the same time, they didn't just come out and say, "He's an artist." So I don't really know what it means. I suppose they don't really have the language to describe me otherwise. But that is the key, of course, because anything new requires new language to understand it. And I think when people don't have the language to discuss you they discount you, or they say things like, "Oh, he's a poet." It's not quite giving me my own pigeonhole just yet, but it's better than being pigeoned in the wrong hole, if that makes any sense.

What kind of experience do you hope viewers have when they encounter your work?

I don't think I want any particular response. When people can get beyond the ragtag nature of the materials used—you know, a bottle, a jar, a marble, something found in the street—they construct their own poetry. I mean, I've had instances where people have come out of my shows weeping. They recognized that the bottles are a little anthropomorphic, and that the little cluster of them is a little family group, like five individuals lined up waiting for the bus; that the way they dangle by their necks is a little precarious and a little sad, suggesting things that are not so easily spoken about in mixed company, if you will. Lynchings, for instance, and hangings. There's a pathos that exists in these objects and the way that I combine them, and people respond to that. I also get, "Oh, your work is so much fun!" But there's another component here too. It's kind of a tears-of-the-clown kind of an idea. I'm always the life of the party, but you don't want to see what happens when I get home.

What kind of art do you like to look at personally?

Growing up in south Texas, I had very limited exposure to what you would call contemporary art, but I looked at the Impressionists and I was always transfixed by van Gogh and the mastery of his picture-making and the way he put paint down like it was alive. But as soon as I did come of age I always responded very strongly to Minimalists like Donald Judd and Carl Andre. I always found them very difficult, but there's a simplicity and a clarity that I find very beautiful, and I guess that's because they address truth through simplicity and clarity that doesn't pull any punches. My work is very truthful—there aren't a lot of gags and hidden tricks, everything is pretty much balls-out.

But actually, and people find this very strange, I'm mad for quattrocento Italian painting, especially Sienese panel painting—the early stuff, before perspective stepped in and ruined everything. It still has the medieval quality to it, and nobody had figured out how to make a receding horizon to make a convincing illusion of depth that goes into the canvas. Everything is really flat on the surface, and it all kind of stacks on top of itself. Something in the background looks small, but it still looks as if it's sitting on top of the Virgin's head in some way. I love that spatial quality, and if you were to lay one of those panel paintings down and then pop up the trees, the castle, the wolf, the demon, and the saints like it was a pop-up book, the way they would be arranged is the way that I arrange my exhibitions, where the sculptures float in a certain place of independence and not overlapping each other but one leads visually to the next and then the next. So if you could turn everything in one of my show on its side and lay it flat on the floor and then lift the floor up, it would look like a Sienese panel painting.

And those panel paintings have the same jewel-like colors as your work.

The coloring of that stuff is extraordinary. And they're tiny little things too—the scale of them is amazing. You can see them reproduced in a book, and in the book they're larger than they are in real life. They're really exquisite and they defy scale in a certain sense. And in my work scale is very important. The whole act of laying small objects on the floor makes the way you approach it and the way you look at it from above impart a sense of great power and authority over the object itself. I sometimes feel as if I'm soaring over an ancient landscape and looking down at Babylon or something, and that's an archeological reference that I can easily visualize. I've always been able to look at space omnipotently, as if I'm up in the upper left hand corner. I like to think there's a little bit of everything in what I do.

In Depth

Tony Feher on Why His "Work Is Very Truthful"