Working in any business for the better part of 20 years usually means you’re a survivor. In a profession as fickle as art dealing, this goes double; to be successful, gallerists have to be light on their feet and firm in their convictions as they navigate the shifting tastes and changeable clients that so often characterize the art market.

Few understand these struggles as intimately as Derek Eller, the artist-turned-gallerist who has quietly helmed his eponymous gallery since 1997, working out of various locations around Chelsea. He’s dealt with rising rents, financial downturns, and disaster-grade flooding (remember Hurricane Sandy? Eller does) as he’s built his business from the ground up.

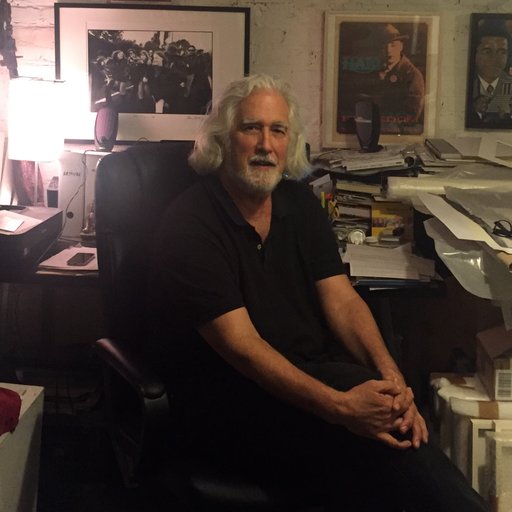

Derek Eller

Derek Eller

His gallery now boasts an impressive roster of strongly idiosyncratic artists at all stages of their careers, ranging from the septuagenarian and Hairy Who co-founder Karl Wirsum to of-the-moment art-fair attractions like Despina Stokou. Still, he’s not in the habit of resting on his laurels—he knows just how hard the going can get, sometimes over the course of a single night.

Now Eller is in the midst of another exercise in adaptability; he’s pulled up his stakes in Chelsea and decamped to a renovated garage in the Lower East Side in a quest for more space and increased foot traffic, two simple factors he says are key to any gallery’s success. It’s an indication of both the waning fortunes of the Chelsea art neighborhood that Eller and his contemporaries helped to jumpstart, as well as the gallerist’s willingness to change with the times. By all indications, he’s not looking back.

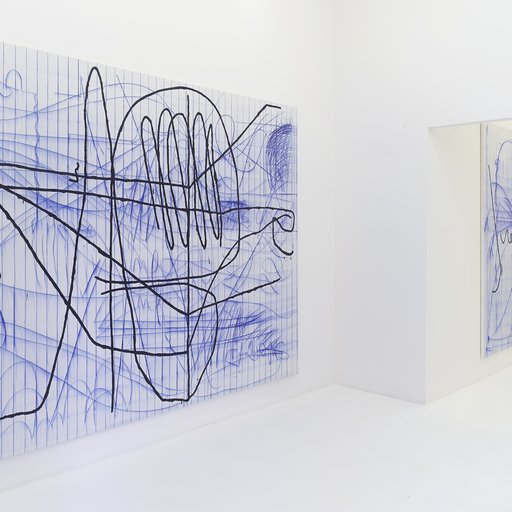

Artspace’s Dylan Kerr met with Eller in the midst of his first show in the new Broome Street space—an impressive array of works by the Danish artist Peter Linde Busk—to learn more about facing challenges and finding love in the rough-and-tumble New York art world.

You just reopened your gallery here on Broome Street after spending years building your presence in Chelsea. What prompted the move?

We’d been in Chelsea for over 18 years, and the block that we were on before, West 27th Street, was a pretty exciting place to be when we first moved. Ten years ago, it was my first ground floor location ever. My previous two galleries were both upper-floor spaces, so moving to a ground floor gallery was a big deal at the time. We moved over with a bunch of other galleries, maybe six or so.

It was a really good move for us, but over the course of that 10-year period a lot of those galleries went out of business or moved away. By the end, we were the last one left. Wallspace unfortunately closed last spring, and then Foxy Productions decided to move. Once we knew Foxy was leaving, we thought we couldn’t be completely alone there. I guess we could have, actually—it would have been more cost effective to stay in Chelsea.

Really?

My rent would have been half.

Wow.

Maybe it wouldn’t quite have been half, but we’re also talking about a total renovation of this space—this was an auto-body garage originally. It was a huge investment just to turn it into an art gallery. But it felt like the trajectory was trending down if we had stayed in Chelsea, just in terms of foot traffic and visibility. I think there’s more energy down here, and there just aren’t that many spaces like this on the ground floor in Chelsea.

On a personal level, I really enjoy coming down to the Lower East Side and seeing shows on my weekends. I like a lot of the dealers down here. It just felt like it could be a nice change.

What’s the importance of having a nearby community of fellow dealers and art enthusiasts?

I think one of the most important things is that people just come and see your shows. We do good shows, we have artists that work hard to put on good shows, and we want people to see them. When we were with a group of six other galleries, there were people circulating around the block. Here we’re pretty central, so if you’re walking around the Lower East Side, there’s not really an excuse not to pop in unless you just have no interest in our program.

On the other hand, you could easily go see a show at Matthew Marks or even Gagosian in Chelsea and miss us at our old location. We were just a couple of blocks from there, but, psychologically, having to go those extra couple blocks and cross 11th Avenue was probably sometimes too much to ask.

Where do you think Chelsea is headed now? Clearly, you decamped.

I don’t see that many interesting young galleries opening up in Chelsea now. It seems that they’re doing something in Bushwick, or doing something in the Lower East Side, or in Harlem, or somewhere else off the beaten path. For the most part, it’s not so affordable. I think my initial rent when I was in Chelsea was $1,200 or $1,300 a month, and it wasn’t a small space. Now, I don’t think you could rent anything for that price.

I’d imagine you couldn’t even come close.

No, no. So where is Chelsea heading? I would imagine that the larger galleries that own their spaces will stay long as they want to, until they feel like it makes sense to sell and let their space be developed. I don’t see why those galleries would go anywhere until then.

Part of me was a little apprehensive about leaving that area, but in the three weeks that we’ve been here I already feel like there are more people walking around Broome Street than West 27th Street. Maybe people are just curious because we’re new, but I do think there are plenty of people who circulate the Lower East Side.

That said, it’s imperative that we maintain a presence at art fairs. It just seems like more and more collectors are only going to art fairs and aren’t coming to see every show and every gallery in the same way that people were doing years ago.

Do you ever wonder if the brick-and-mortar space is becoming a thing of the past? Is location really so crucial anymore?

If I believed that were the case, I would have just stayed put in Chelsea. But artists want to do shows. They don’t just want to have a piece or two at an art fair. They just don’t want to survive off of online sales. And they want to put up an exhibition, to push themselves and push the work.

Our last space had a main central gallery, with a column right in the middle of the space. The ceilings were maybe 11 feet high. It was fine. It was a nice space. We did big shows, we did intimate shows, but this still feels like an upgrade to me. Our ceilings are now over 18 feet, there’s not a single column in the space, and it just seemed like it would present new challenges for artists. It gives them something to be excited about.

A big question is how to maintain relationships with artists, because there are so many galleries out there. Artists—if they’re any good—have a choice. They can move on, they can go somewhere else. It’s a combination of the personal relationship, the space itself, and the program of the gallery that keeps them loyal and interested. I wanted to keep things fresh for people who are already working with us and interesting for those who aren’t yet.

I’m glad you bright up developing and maintaining your relationships with artists. As someone who’s worked with both younger emerging and older overlooked artists, how do you care for and cultivate an artist over the course of their career?

That’s a great question, and I don’t know that there’s an answer that applies to every situation. We’ve been supportive of artists at times when there’s not interest in their work, and not a lot of galleries do that. Most careers have peaks, valleys, and plateaus, and very few artists have the good fortune to just ride an uphill trajectory the whole way.

I’ve been extremely loyal to people, and we’ve had artists who have been with us since the first season, guys like D-L Alvarez and David Dupuis. They are two artists that I find extremely interesting, that I trust 100 percent, and that I believe in, but we’ve had periods when we do extremely well together and periods when things slow down. One thing we can always do is remain supportive.

We can offer guidance, we can make efforts to connect them to people and promote their work, but there’s a lot we can't control, and a lot that the artists have to do for themselves. On some level it does come down to the work, but even things an artist does or does not do outside of the studio in terms of building a community for themselves where other people are also supporting and talking about their work are, unfortunately, so important.

Have you noticed a shift in the level of self-promotion and the importance of on- and offline networking since you started working?

There have been cases where I’ve found it very helpful that the artists are out there doing their own thing, and other times when I want to say, “Hey, I wish you would pull back a bit.” I’m generalizing here, because some artists aren’t involved with any of that. We work with a few artists—I probably shouldn’t say which ones—who don’t even carry cellphones.

Going back a bit, what were you doing before you started your own gallery? How did you get into this business?

I was working as a waiter prior to opening the gallery. I’d gone to a college at the University of New Mexico and graduate school at the Art Institute of Chicago, both for studio art. I went straight from high school to college to graduate school, so I was 23 when I got out of grad school. I moved to New York right after.

I don’t think I was particularly prepared to move to New York and figure out how to be an artist, but I came here, got a job as a waiter, and continued to make art more or less in private for three years. At that point, I realized I wasn’t committed enough to what I was making nor was I really enjoying the process of being in the studio enough to say, “Hey, I’m willing to be a waiter indefinitely to pursue this dream of mine.”

The art gallery thing was really just a crazy idea. If you don’t mind me being perfectly honest, I think I was pretty naïve. I was probably just another young artist—with an emphasis on young—who walks around and sees shows and thinks, “Uh, this sucks. I could do a better job. I should open a gallery.” I had no clue how difficult it would be to operate a gallery, not only to find good artists but then to find people to support that work. I just didn’t understand.

From that perhaps unlikely starting point, how did you get on your feet early on?

It’s sort of a funny story. I got a side job off a friend—this must have been early 1997 or so—where I ended up delivering a couch to Lisa Yuskavage. This friend of mine said to her, “Hey, my friend Derek is opening a gallery.” And, she said, “Oh, you should go talk to Bill Arning.”

Bill Arning was at that time the director of White Columns, and he was nice enough to meet with me. I remember going in and saying, “Hey, I’m opening a gallery.” And he replied, “Well, you know Derek, usually people work for galleries for five years before they open one.” And I said, “Oh shit, it’s too late. I already signed a lease.”

I really went into it fairly clueless. That’s not to say I didn’t have something to bring to it—I obviously have an arts education—but I just didn’t know a lot about the business aspect of running an art business. Luckily for me, I think there were only about 30 or so galleries in Chelsea in 1997, though I could be wrong about that number. It was a year where a lot of galleries were starting to open in Chelsea, and it was really inexpensive. The rent for my first space was affordable, and I had enough money to basically get me through one year of business. I was still waiting tables on my days off, just to know that I had that extra hundred bucks on hand, which was a big deal.

We opened in September of ‘97, and I don’t think we made a sale until the end of November. I remember the first sale was such a big deal, and it was to somebody who had never bought art before. It was just funny—I had never sold art before, he had never bought art before, and it was pretty meaningful for both of us.

One good thing was that we got press right away. It was very fortunate that we got reviewed pretty quickly, and people were supportive. And because we opened in this art-mall building, which was 529 West 20th, there were actually a number of pretty decent galleries in that building, and people visited and circulated through. Just being in that mix really helped us connect with new people.

I was broke at the end of my first year, but I remember thinking, “I’ve got to open a second season, I’ve got to do this.” I was using credit cards, and at a certain point—not quite then—I got a line of credit with the bank, but I was very fortunate that we finally had a show that brought in some money in 1998.

What was that show?

It was a guy named Andrew Masullo. He was at a different point in his career for us. We were a brand new gallery with no track record, and he had shown with André Emmerich—so he had a career and had sold quite a bit of work at that point, but he wasn’t with a gallery at the time and we had some connection with him through another artist. He took a chance with us, and we were lucky enough to do some business. For the first time, we had some money in the bank after that show. That probably was one of the things that kept us going.

What was your learning curve like? How did you acquire the skills that have kept you in business for almost 20 years?

For the first five or six years of the gallery, I did everything. I was the art handler, photographer, salesperson, receptionist—everything. I would say I’m still learning. It’s been an amazing education, and it’s really forced me to grow as a person. In a lot of ways, I wasn’t really designed to be the art dealer type.

How so?

I don’t think I realized how social of a business it is. I’ve actually learned to really like some of that, but it didn’t come naturally to me.

Every step of the way there has been something new to learn. And we’re still learning. I say “we” because we’re a team at this point. It’s interesting—my wife and I have been together for almost 19 years, and we met because of this.

Do tell!

In addition to working as a waiter before I opened the gallery, I briefly did window displays at Macy’s. I worked with some guy who was an artist, and I remembered that his girlfriend had opened a gallery in Chelsea. When I had this notion of opening a gallery, I thought, “Who do I know who has a gallery? Oh, wait a second, the girlfriend of that guy I did window displays with.”

It was a woman named Elizabeth, who happened to have a partner named Abby, who’s now my wife. They ran a gallery called Clementine. Abby and I started dating within a few months of opening my gallery, but she continued to run Clementine with Elizabeth until 2008.

We were competitors for a number of years, which was tricky. It’s such a competitive business, and it was hard to navigate that. It’s almost like when two artists are involved, or two actors, whatever. Sometimes, having two art dealers both trying to get the same limited collectors can be a little harmful. There were days when nothing had happened at my gallery, but when we got together she’d say, “Oh, it was amazing. We sold $2,000 to so and so.” That can be tricky.

So how did you two divide work and play?

It took a lot of years. You just need to get a thicker skin and become a little more detached, to feel secure with who you are and what you’re doing and to just be happy for your partner. I say this speaking for myself. As my business became more established and I was able to feel more confident, it was easier to have a competitor as a partner.

They decided to close in 2008 right when things were starting to head downhill—I think they saw the writing on the wall and decided that they weren’t committed to keeping Clementine open at that point. Abby and I decided to work together after that and it’s been really nice. It’s more of a team effort now, and of course I’ve learned a lot from her, too.

You’ve weathered all kinds of different art markets over the years, from the rising tides of the late 1990s and early 2000s to the 2008 crash and the red-hot buying frenzy of recent years, which may be cooling down now. How do you stay on track and keep the proverbial lights on in these shifting conditions?

It’s always a challenge. We’ve seen a number of challenges—after September 11th there was a dip, 2008 was the crash, and after Hurricane Sandy things slowed down, too. Where we were, between 11th and 12th avenues, everybody just got wiped out.

What was your experience during that time?

Oh, it was just awful—completely surreal. A large percentage of our inventory was stored underground, in the basement.

Oh no.

It’s funny, because when Hurricane Irene hit [in August 2011], we had a small puddle of water about six inches wide in the basement. The next year, a friend of mine who was an art preparator at a major gallery offered to help me prepare for Hurricane Sandy. The two of us went over there the night before and made sure that everything in the basement was at least a foot off the ground, for insurance reasons and safety of the artworks.

Honestly, I thought, “God, this is totally unnecessary. What’s going to happen? Another little puddle?” I can even remember thinking even during the night of Hurricane Sandy that the storm didn’t seem as bad as it was supposed to be.

To make a long story short, our basement turned into an 1,800-foot swimming pool. We had roughly 700 works of art underwater for two days. It was a total nightmare, a disaster. Such a tragedy. I don’t think that anyone saw it coming. If we thought that something like that would have been possible, we would have had everything out of there. There had just never been anything like it before. Again, I thought we had gone above and beyond what was necessary to make sure everything was safe.

How did you bounce back after such a devastating event?

It was hard. We were shut down for two and a half months, and for six months we were basically just focusing on insurance claims. It was really hard on us, and the artists.

I bet. Seven hundred works….

That’s not an exaggeration. There were portfolios of works on paper, sculptures, paintings, you name it.

We survived in part because I’ve always been cautious, conservative, and careful with money over the years. Not that we don’t spend money, but we’ve taken modest salaries and kept the rest in the business. I think it’s because of the years of living hand-to-mouth and the stress that comes with that. There’s still as much stress today, even with money in the bank, but the stress of wondering if you’ll be able to pay your rent next month is maybe easier to deal with when you’re younger. We’ve made a point to save money when we can, and that’s gotten us through when times are slow.

Of course, we cut back when we have to. I remember there were times, especially in 2008 when the phones weren't ringing and nobody was buying much of anything, when we weren’t going out to dinner—we were making peanut-butter sandwiches and bringing them to the gallery. We’d order pizza after an opening, things like that. We had to let an employee go at that point. It wasn’t easy.

Its funny. Now we’re upping the ante and going all-in with this move at a time when things are, as you say, possibly a little tighter than before.

Things do seem a little slower in recent months. The spring auctions were a bit lackluster, and Clifton Benevento closed their doors for good today. I heard right before coming to meet with you.

Which was a shock, as it’s a shock any time a gallery I respect decides to close their doors. Of course, who knows why? Another art dealer who had a partnership close down said to me jokingly, “Derek, art galleries don’t close because they’re making too much money.” That said, some galleries close because they can close.

For myself, I need a job. I never had a trust fund or an investor or anything like that—I’ve actually made my living doing this for the past 19 years. Even if there are years when we’re not making much of anything, living off the profit from years before, I’ve managed to survive. I’ve never owed anyone any money, and I’ve never been one of those gallerists who don’t pay their artists. I’m really fortunate in that sense.

You have adapt and adjust. When I first opened, there were shows I really wanted to do but that I just didn’t have the money to ship across the country. This show, for instance, was very expensive to put on because we had to crate and ship everything from Berlin. If there were financial issues I couldn’t do it. It just depends on where you are in your career, what your cash flow is like, and whether you think the show has any chance of paying for itself. Not every show pays for itself, believe me.