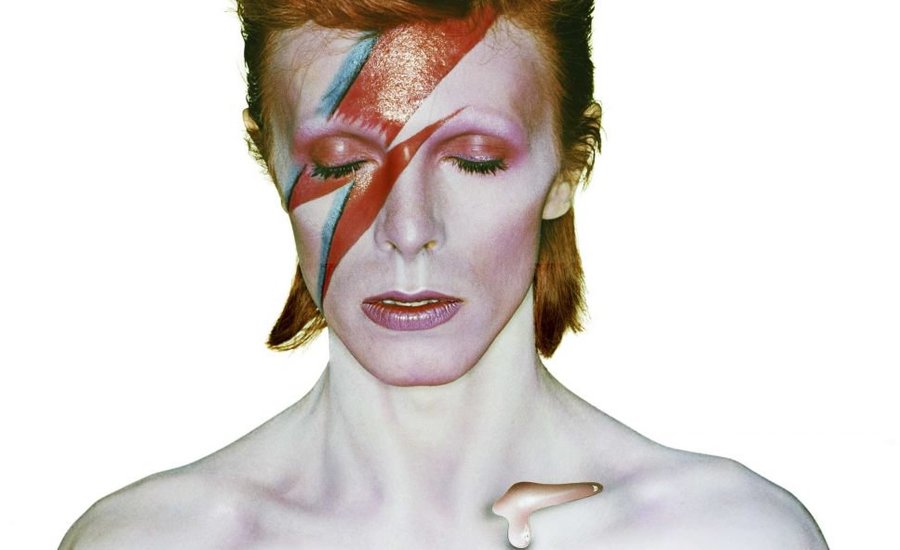

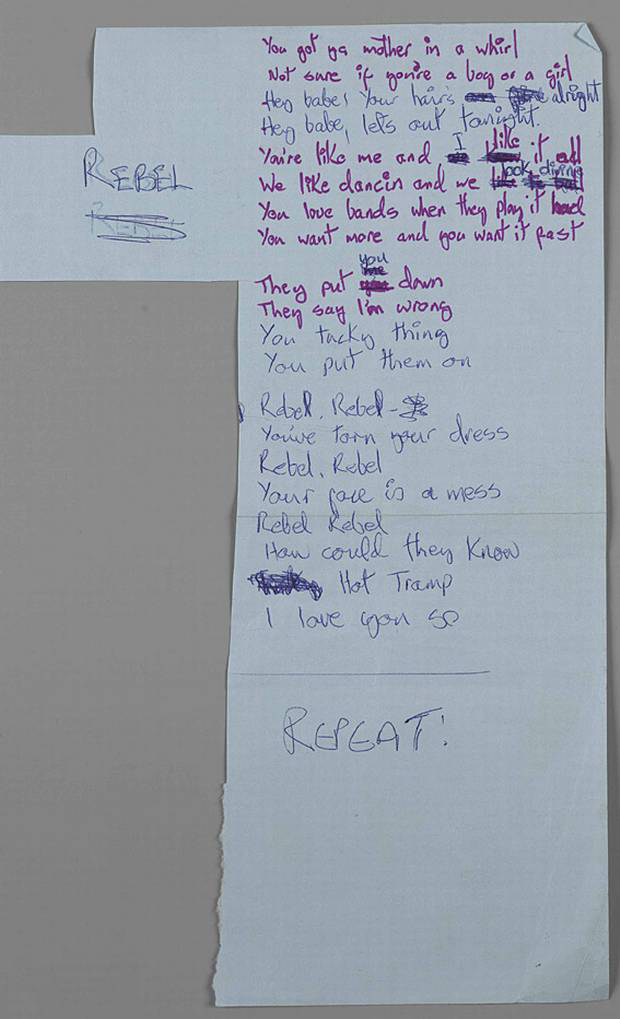

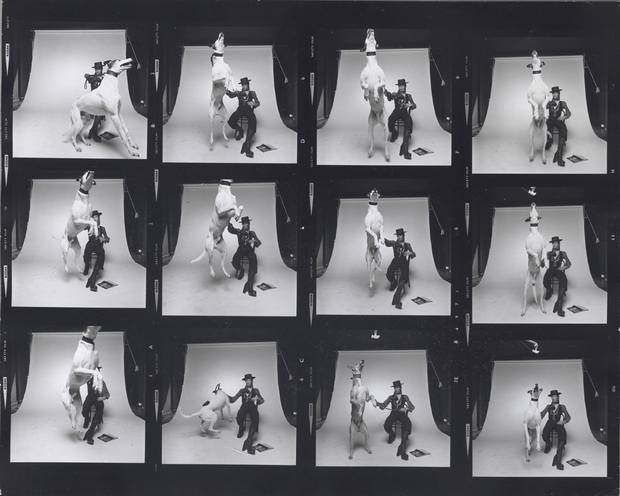

The much anticipated "David Bowie Is" exhibition is finally on its way to its last stop after its five-year tour around the globe: the Brooklyn Museum. Opening March 2, the exhibition will feature over 400 relics from the artist's personal archive, including original costumes, handwritten lyrics, photographs, videos, and original album artworks. Tracing Bowie's creative process from his teenage years in England to his last years living in New York City, the exhibition sheds light on the intimate creative process of the man who continually revolutionized music, fashion, and identity.

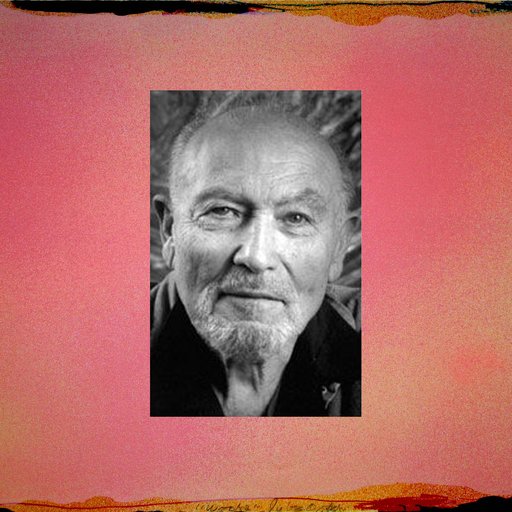

In honor of the final installment of the show, we've revisited a 2013 conversation conducted during the first showing of the collection at the V&A Museum in London with co-curator of "David Bowie Is," Geoffrey Marsh. It's important to remember that when this exhibition was being organized, David Bowie was still alive. (Bowie passed in January of 2016, just two days after he released his 25th studio album and celebrated his 69th birthday.) Here, Marsh talks about how it all started, and how it all, eventually and not without challenges, came together.

---

We were close to staging an exhibition about another music star and we got very close—we even had it in the diary. But it got bogged down with copyright issues that we couldn’t solve. Someone who knew about that rang me up and said they’d heard it wasn’t happening and asked if we were interested in doing any others. I happened to know that this person was involved with several performers (though at this point not David Bowie) so I wrote back a polite letter saying that we were always interested. There’s no problem finding music stars who want to have exhibitions about themselves, the real problem is finding relevant collections because most of them have been sold or thrown away.

So in the museum we made a sieve through which we put a long list of names: they had to be pretty significant, they had to involve art and design and performance, they had to have some connection to today and so on. Doing that you get down to a shortlist very quickly. There were seven or eight names on the list and he said, "Well I know some of these people; I’ll get back to you." There was a long silence and finally we got a call back saying "actually I have a connection with David Bowie’s archive, which was one of the names on our list, would you be interested?" So we went out and had a look—this would have been January 2011.

The agreement was that we could borrow anything from the archive and that Bowie would have no involvement at all and the only agreement was that all the text in the exhibition would be checked by his archivist for historical accuracy—the interpretation itself would be the museum’s entirely.

At that time I certainly got a strong feeling that he wasn’t doing anything, although in actual fact, he was just starting to stir. My feeling is that if he’d really been into an album by then he wouldn’t have done an exhibition.

It’s been said that you found out about the new material the same day as everyone else—you must have had an inkling, surely?

The funny thing is that Jonathan Barnbrook designed the cover of [new album] The Next Day as well as our book and exhibition but obviously didn’t mention anything to us. He kept absolutely silent. However, by early December I got a feeling that Bowie was working on something. I can’t really say why, but it’s like having a relationship—you get a feeling. And obviously with his birthday coming up…

The irony was I decided to stay up all night on his birthday and as soon as the website went down I thought, "Yes!" Then, about half-past-two in the morning, I feel asleep and missed the song going up! But it is kind of curious to think that during most of the time we’d been doing the exhibition he’d been working away.

People ask me what I think about the single ["Where Are We Now"] and I actually think it's him clearing out his attic because he wants to move on to something else. I think the exhibition is possibly a bit like that too.

People say it’s nostalgic and I don’t think it’s nostalgic at all. I think what he’s really saying in it is that as you get older, if you just hang around your memories, you just end up as a relic on the side and if you want to actually do anything creatively you’ve got to dump all that. And I think that’s sort of what he’s beginning to do.

So what was it like walking into the archive the first time? It's a huge place in Boston isn't it?

I can’t say where it is. I can say he’s had this archivist working on it for four years and it’s beautifully documented—to museum standards in fact. He’s obviously very interested in technology. There are pictures of him as a baby—a photograph of Little Richard that he had on his bedroom wall as a little boy which is in the exhibition. The first few times we went there we were working from photographs.

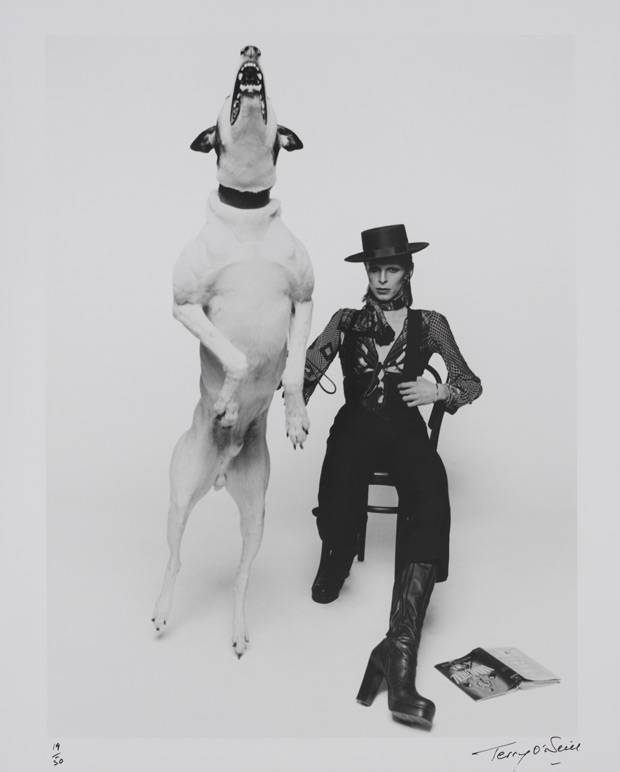

The first thing we actually saw were the costumes. And the strange thing about costumes is that when they’re sitting in a box, folded up, they don’t look like much. But then you conjure this image of them on stage and weirdly, they’re like freeze frames of how he saw himself at that moment—even more so than album covers that could take more than a year to come out. The costumes were something that were probably designed only months sometimes days in advance.

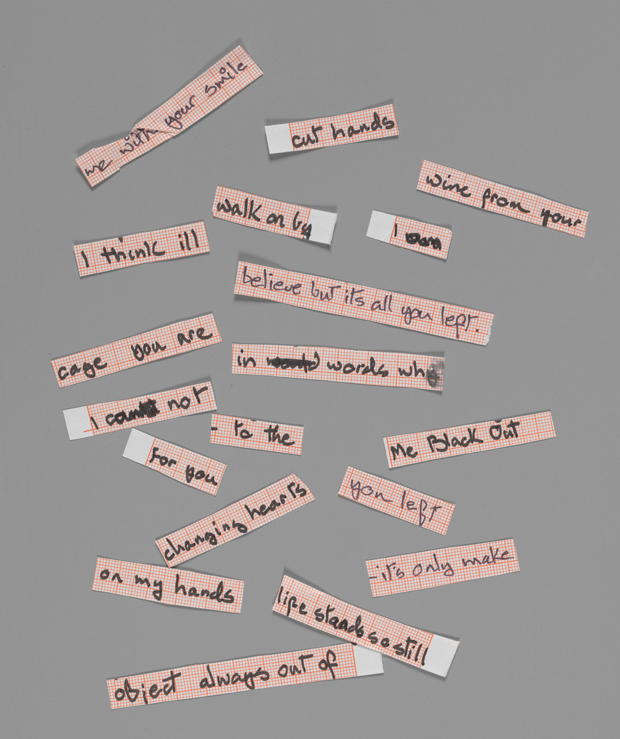

It’s like having a film of his career. Some of them have become so iconic—for instance the Pierrot costume from Ashes To Ashes. Looking at that you think, what’s all that about? Where did that come from? And I think the thing that got me—my Bowie moment, if you want to call it that—was when I realized that he had made all the drawings for the original designs himself. We have the felt tip pen sketches he made in the show.

Also in the exhibition we have his original designs for Hunger City for the Diamond Dogs tour. He actually got as far as trying to turn it into a film. We have the storyboards he made for it so we’re animating them in the show. If you think that he was doing this when he was just 26 or 27 years old, it's incredible. There’s a big difference between going to see Judi Dench in Cabaret and a couple of years later thinking I’m actually going to put on a full scale musical myself. He never lacked ambition! But all we see (as fans) are the tips of the icebergs of the things he was working on that actually got through.

So how do you go about tying a curatorial ribbon around all that?

Well, we read a huge amount of books on Bowie—around 60 with his name in the title alone. A lot of them are chronological and we didn’t want to do it like that. Like most of our exhibitions here we wanted to look at the process. We thought about it thematically. And although when we started, he appeared not to have recorded for a long time we never saw this as being a retrospective, summing-up kind of show. One of the strange things about doing an exhibition like this is that you get people who come to Bowie at all sorts of different periods, the '70s, the '80s the '90s. I think both of us [Marsh co-curated the show with Victoria Broackes] got to a point where we wanted to pull back from it.

Having gotten steeped in it, we both thought, "If we get into too much detail here it’s going to end up as nothing." Paul Morley at one point said, "Why don’t you just not have any sections and any order at all? Why not just put all the objects out?" It’s an interesting idea but at the end of the day things have to go into cases because people steal them and all those sort of practical requirements. However, as a conceptual idea for Bowie you could imagine it like one of those extraordinary photographs you see of people picking over rubbish heaps in say Manila and making a living out of it. In a strange way Bowie is picking over cultural ideas like that.

So we got to a point six or eight months ago where we realized we’re never going to get to the point for a typical V&A visitor who wants a definitive show, or to fans who just want to see the stuff or designers who want maybe something else again. So what we thought we’d try and do is crush time completely—that’s one of the things he’s interested in. So the captions are written in the present tense.

To give credit where credit is due, Paul Morley was the person who thought up the title, "David Bowie Is." We thought a short snappy title like that wasn’t going to put off people who only liked Bowie from a certain period. It’s a sort of question of what he is but also it’s also just a statement. And somewhere between those is what we as curators wanted to do with the exhibition.

This article was originally published on Phaidon.com.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Five of Warhol's Starriest On-Screen Portrayals, From "Death Becomes Her" to "The Simpsons"