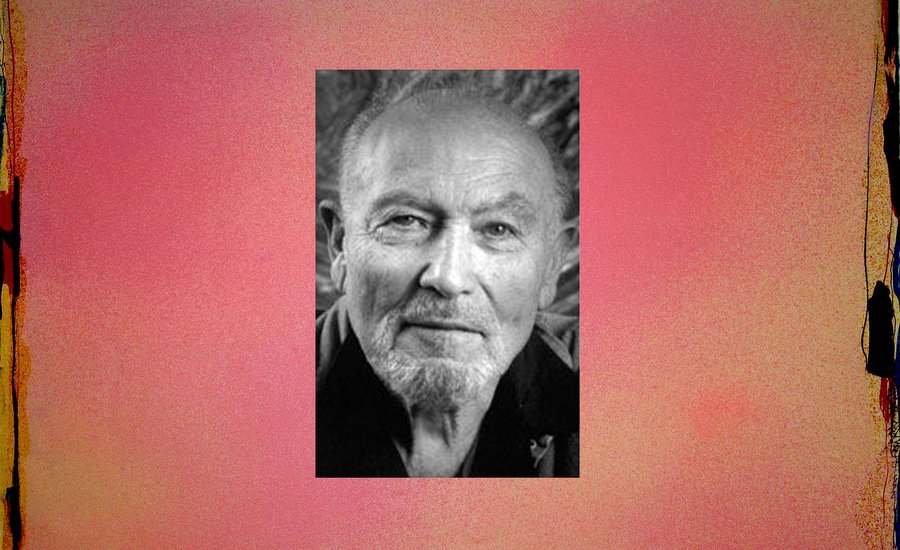

Jules Olitski was born in what was then the Soviet Union, in 1922—just months after his father, an official of the Communist Party, was executed by the Soviet government. The next year Jules and his mother and grandmother immigrated to Brooklyn, where he was deeply impacted by an early experience at the New York World's Fair in 1939 when he saw the portraits of Rembrandt van Rijn, a Dutch old master painter. From then on, Olitski was hooked on painting, and while an art student, he discovered abstract art at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, which eventually became the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Fast forward, and Olitski is considered by many critics to be one of the central figures of modern abstraction. Most known for his spray-painted color-field paintings done in the 1960s and '70s, Olitski became the first living American artist to have a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969.

In this 2002 conversation excerpted from Phaidon's Speaking of Art: Four Decades of Art in Conversation, Olitski speaks with art historian and critic Jean Wainwright about the value of both keeping and breaking traditions; his use of unconventional painting techniques and how his work was received by critics; and why he believes it is vital to offer viewers a sense of aesthetic pleasure in a work.

...

You have said that an artist’s vision does not strike him in the face with an “Aha! Now I see the truth” response. It lies quiescent. It waits. You have also stated that you often find your work is like a landscape of dreams. I’d like to talk, first of all, about these two statements in relation to your early works of the 1960s and 1970s, and to your role in the post-painterly abstraction movement.

Well, the first quote you read is something I wrote in Studio International, and it probably sounds more profound than it was meant to be. What I meant was that, since the artist is also the artisan who does the work, in a sense, the expression gets made willy-nilly as the art gets made. If I were beginning to paint a picture, then I could say, “Well, now I’m going to express my vision. There it is. It is as it is.” Take an artist who I admire, Kenneth Noland. He had a vision he expresses that you immediately recognize. But looking back at my own work from the 1950s you might say “My god! This man has had so many visions, which one is his? There have been paintings that were almost monochrome and ones that followed that were thick with movement—Sturm und Drang, almost—so is that his vision?” The painting I make now look rather different from the ones I did five years ago. I suppose I have to say there have been many visions, and yet to my eye they’re all related. An artist takes possession of the canvas, and his vision, I believe, is expressed in the design of what happens there. Some artists say, “It means whatever you want it to mean, and there it is."

The second passage you cite is somewhat poetic. I’ll try to quote it exactly as I remember it, "Behind every artist's mind there is an architecture. There is a design. It's like a landscape of his dreams." Now I think what Gilbert Chesterson was saying, if I understand him, was that this "landscape" was his vision of reality. I think that honest paintings express how things work in reality, in the universe.

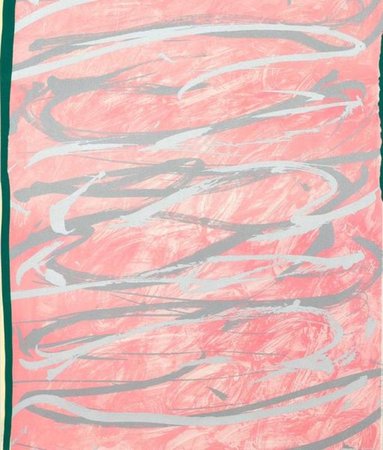

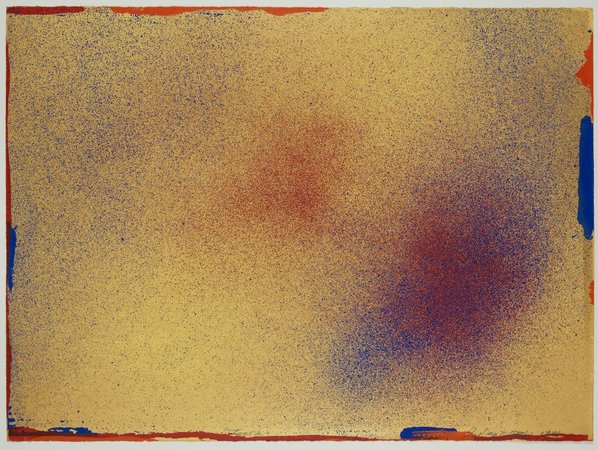

"La Boca Love Song," 1988, Available for purchase on Artspace

"La Boca Love Song," 1988, Available for purchase on Artspace

You've talked and written quite extensively about critics and the way they've approached your work through the years—particularly your early works, and, later, the spray paintings that you pioneered. Can we talk a little bit about the reaction to those early paintings and when you changed from talking about the edge to the spray paintings.

If I theorize about what is going on in my art, I do so after the making of it. As I think I've said before, an artist might become frightened by what he has done. He's alone with the work and will seek reassurance from himself. Take the pictures that were shown at the Venice Biennale in 1966—I guess you can call them window-shaped with a monochrome surface, but with drawing at the edge. I looked at them and I said, "Well, it makes, I believe, perfect sense. Yes, the edge of the shape can be seen as drawing, as line." But when I did it I surely wasn't thinking of that. I felt impelled to do it and to see what it would look like, and it pleased me. I do something because it pleases me to do it. [laughs] Maybe it's just as simple as that. I take pleasure in it. As Schiller said, man is most wholly himself when he is at play. An artist hopes that the audience will look at his work and find pleasure. I'm not sure that art ennobles—that it makes us better, more moral. Let's hope it does, but I don't see any evidence for that. That said, I'm not against political art or feminist art. I would just ask that it's pleasing to the eye.

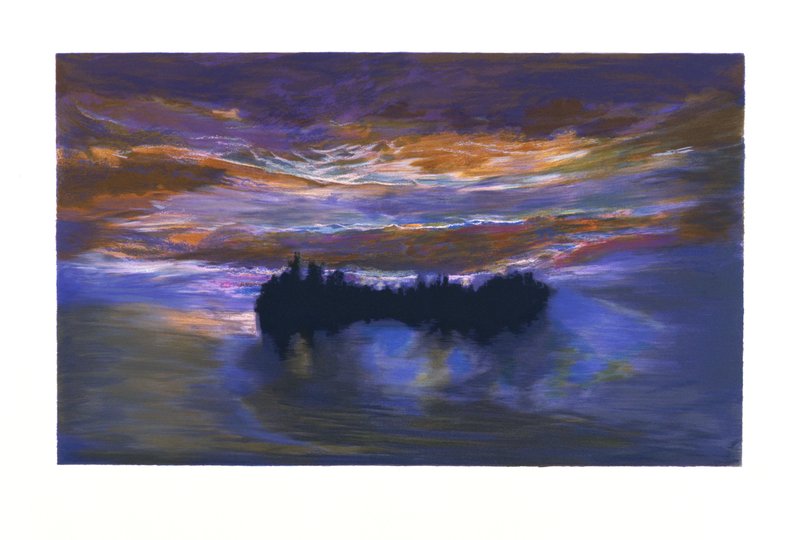

"Elegy—September 11, 2001," 2002, Available for purchase on Artspace

"Elegy—September 11, 2001," 2002, Available for purchase on Artspace

You were, of course, cited by Clement Greenberg as being "the greatest living painter."

What Clem said meant a hell of a lot to me. I suffered a lot of burdens from it—not everyone was pleased, you know; my dear friends were especially displeased—but I wouldn't sell that sentence for the world! [laughs] He also said how wonderful it would be to put an Olitski next to a work of high art. And that, I think, is the challenge. Is my work as good as that of the great masters? That's a fearful thing to contemplate, but that is what one must feel. It's not enough to be as good as, or better than, anyone else alive. An artist should take it for granted that he or she is.

You're celebrating greatness and celebrating the fact that you're continuing an art-historical tradition that many artists today are working against.

Yes, I feel that I'm part of the tradition. Tradition is not something that stays still. A tradition is a tradition because it continues. Of course, there are traditions and traditions. The first painting I saw as a kid at the Brooklyn Museum were watercolors by John Singer Sargent. But the painting that really knocked me on my ass when I saw it at the New York World's Fair in 1939 was a Rembrandt self-portrait.

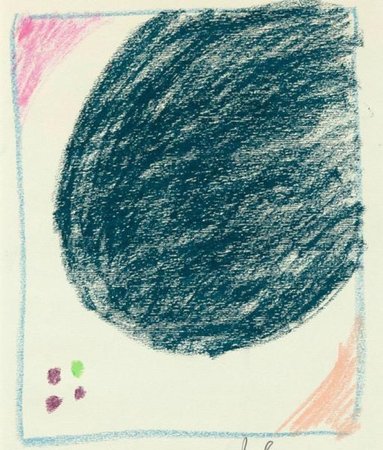

"Untitled," 1964, Available for purchase on Artspace

"Untitled," 1964, Available for purchase on Artspace

But you have also talked about breaking with tradition. Of course, you were responsible for breaking a tradition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, because you were the first living artist to have a show there. Can we talk a little bit about that? It was a very important moment.

By all means, I had quite a few rather large sculptures, and one day Henry Geldzahler, who was the curator of contemporary art at the Metropolitan, appeared and just spent about an hour or two looking at them. Then, as he left, he said, "Jules, how would you like to show those at the Met?" And I said, "Yes, indeed, that would be lovely." And he said, "Well, there is one problem. We have a rule that no living artist can exhibit, but I'll call a board meeting and see if we can change that rule." It didn't occur to me for a minute that this could actually happen, but indeed it did. A certain critic was outraged. He said that I was the worst painter in America making the worst sculpture and how dare the Met allow this? He said I must have powerful friends! [laughs] As a result of that piece in the newspaper, the show broke records for attendance. The very worst painter making the very worst sculpture imaginable—people just had to see it.

I'd like to move on now to discuss your current show. The works are very celebratory paintings, with lots of beautiful threads of color and light running through them. Perhaps we could also talk about your wonderful phrase, "Expect nothing, do your work, celebrate," which I think has a marvelous, life-giving force.

Well, I think it is actually lifesaving in the face of seeming nullity that there is a creative force we can turn away from or engage with. If I have this flow of colors—the paint flowing into other colors and flowing over the whole—and then I take a big glob of paint and I walk round and go "pow," without deciding exactly where, the relationship between the two makes for a kind of lovemaking.

"Toora," 1986, Available for purchase on Artspace

"Toora," 1986, Available for purchase on Artspace

You move the paint around a lot through different methods, including blowing it across the canvas. Could you describe how you do that?

It occurred to me what would happen if I got a leaf blower, which has a tremendous roar and really moves the paint, and I began composing with that powerful instrument. And things do happen. I'll think, "Can I use that? No, I can't use that. I'll go over it again." And I'll do something else and something else until I think, "Yes, there's nothing more I can do here."

You have described the way you create your work as being like the extraordinary feeling Frankenstein has when he sees the monster come to life.

Yes, that's when I know it's right. Even if a work looks completely other than what I've done previously. I know it's right. It's a thing we say to each other when we've lived close and seen each other's work. We say, "Does it work?" "Yeah, it works."