Peter Doig is most known for his landscape paintings that he calls "abstractions of memories," which evoke a sense of mystery, as though we are viewing a screenshot of a larger narrative. In this interview with contemporary art curator Kitty Scott, excerpted from Phaidon's 2007 Peter Doig monograph, the artist discusses deriving inspiration from films, why he consistently strives to escape his mannerisms, and how living in a number of different locations around the world influenced his work.

...

When did you know you were going to be a painter?

When I was in high school I quite liked the idea of being an artist. Still, I didn't think I was good enough to be a painter. When I went to art school I thought, 'That's the kind of world I'm interested in, the world of painting and painters, rather than graphics, theater design or commercial art."

And at high school?

Art was always the class I enjoyed the most. I liked the projects and I liked making things. I wasn't much interested in high school and left early to work, but then I went back a few years later to do a part time year at SEED, a free high school in Toronto. I spent most of my time making art.

Your father is a painter. Did he influence you?

When I was a child I saw him working, but he did so very sporadically. So it wasn't as if I had a father who had a studio. He was someone who every once in a while would set up an easel and make a painting. I also had a great aunt, Anne McEntegart, who was a real artist.

Did you have her paintings around the house?

We had some. She was a kind of mythical figure within our family. She had many landscape paintings, etchings, wood cuts, also some sculpture, and had her own press. Her style is hard to describe, other than a kind Scottish/British post-Impressionism. She was not a sentimental artist.

What were the paintings that you made in Montreal (between 1987 and 1989) like?

The paintings I exhibited at Galerie Nomad in Montreal in the late 1980s were quite interesting because they marked the beginnings of what I later started making in London while at Chelsea, and they went on to be the subjects that I became engrossed with. They were quite crude, really. These paintings may have been unusual at the time because they looked almost like a type of landscape painting that viewers weren't used to contemplating in a contemporary art space. I showed the first Friday the 13th painting (Friday 13th, 1987) at Galerie Nomad, as well as Edge of Town (1988-9), picturing a figure walking in to the landscape. A later exhibition in Articule, also in Montreal, included paintings I had made in London before coming to Canada, although a few new works were also included. I remember a painting based on a postcard of the crown jewels.

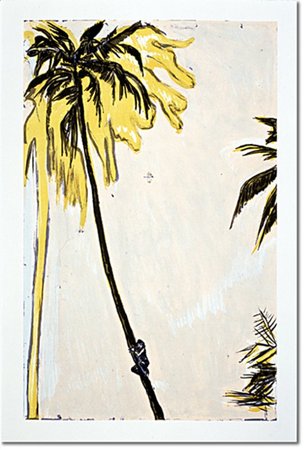

Peter Doig "Fisherman," 2014, Print, Available for purchase on Artspace $1,750

Peter Doig "Fisherman," 2014, Print, Available for purchase on Artspace $1,750

What would you say was the subject of the first Friday the 13th painting and what was the source of the imagery?

The source for this painting is a dream sequence in the original Friday the 13th film. I was struck by its relationship to Munch and also by the plain beauty of this still moment amidst all the carnage. The first painting of mine is quite awkward and more a fut reaction to seeing the scene and making a painting of it—something I had not really done before.

While in Canada you began to turn to Canadian subject matter for your paintings, but you further developed this strand of work when you returned to London in 1989. It is tempting to refer to this body of work as 'the Canadian Period', although you were living in London. What drew you to this subject matter? Paintings such as Blotter (1993) and The House that Jacques Built (1991) come to mind.

I was trying to come to terms with the Canadian part of my life. I left Canada when I was nineteen. I really wanted to get away. I felt bored. London seemed to be where the things I was interested in were coming from. Going back to Canada when I was a little bit older, I realized how much I had absorbed there. It now felt important. For the most part I tried to avoid becoming involved in nostalgia, and that's why a lot of the imagery I used for these paintings were things that reminded me of my experience rather than things that were directly from my experience. People often talk about how I made paintings from family snapshots, but I've never made a single one from a family snapshot. Maybe these paintings remind people of family snapshots.

What about your approach to the surface? The surface of Blotter is very particular.

At the time I was thinking about how the effect of a material could be used to describe conditions of weather or to suggest weather. I had the opportunity to look at painters who had worked in that same vein in Canada. Paterson Ewen was an artist I had never heard of until I went back to Canada. I saw a large exhibition of his work, and it made a big impression on me, as well as paintings by Canadian artists such as Tom Thomson and David Milne. Maybe the surface is an abstraction of the memory of being in a certain frame of mind under certain weather conditions and in certain places.

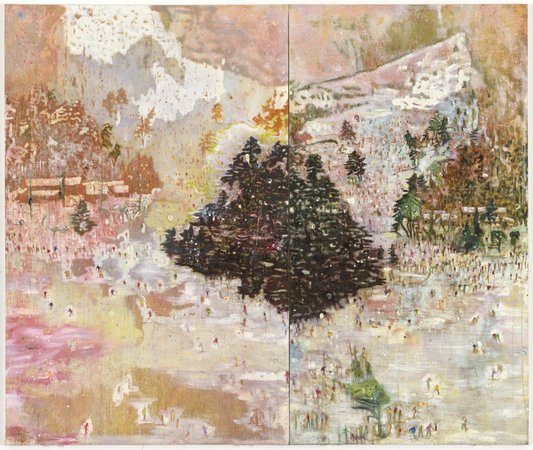

"Ski Jacket," 1994. Image Courtesy of Tate Modern

"Ski Jacket," 1994. Image Courtesy of Tate Modern

It would be wrong to leave readers with the impression that while you were in London you were looking back to Canada exclusively. At the same time you were exploring your own picture archive. The split canvas Ski Jacket (1994) is a work from that period. What would be involved in making a work like Ski Jacket?

Many of the paintings were not 'Canadian' at all—they just ended up looking that way. Ski Jacket was based on a photograph from a Toronto newspaper of a Japanese ski resort. It reminded me of a black and white oriental scroll painting. The original photograph was tall and narrow. I started by making one panel, but the scale was wrong—it seemed too narrow. So I made another panel the same size that both mirrored and distorted the original panel. It had this central bushy area that everything else seemed to flow out of. At the time I had made a relatively few paintings with figures in them, and so I thought why not make a painting with hundreds of figures in it, representing them with little flicks of color. When you look closely you realize from their oddly contorted body positions that many of the skiers are beginners—a lot of them are struggling to stand on their skis.

What about your treatment of source photographs?

Sometimes paint gets spilled or sprayed on them, and it adds an unexpected layer that you can then refer to. The reality of the original feels less constricting, and this provides an opening. It takes the reality away from the photograph and turns it into a more abstract image.

You have an interest in vernacular buildings and iconic buildings like Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation at Briey-en-Foret. You made a dark and disturbing series of pictures about that particular apartment complex as seen through the forest. But you are also drawn to more vernacular structures. Here I am thinking of the Canadian-type houses you have repeatedly painted—there is one in Daytime Astronomy (1997-8) and another in Iron Hill (1991).

I have made relatively few straight landscapes that didn't have any architecture, and I always wanted a landscape to be humanized by a person or a building, at least something that suggests habitation. The structures I started with were pretty modest. I wanted to make some homely paintings. You have to remember the kind of art that was being exhibited at the time. In the late 1980s and early 1990s most art had a clean, contemporary, slick look. Often this work was process-based or referred to Minimalism. It was highly polished or manufactured to specification. I didn't want to become a part of that world. I purposely made works that were handmade and homely looking, and this was often the subject of the work as well. I started with very modest homes, like cabins. So I started by painting a cabin, and then I moved up the line. I became more interested in what buildings represent. How, in a very modest structure, did someone decide to place the windows? Often they seemed to be anthropomorphized. I never invented the buildings I painted—others invented them. The House that Jacques Built had that kind of mad Jack Palance face that looked like it had been damaged by a fire. It was completely blackened and had these blackened eyes. That led to making paintings like Bob's House (1992), which was based on Robery Motherwell's house. (I had found a picture of his Cherokee parked in the snow in front of it.) The house seemed like an odd place to be making the paintings he made inside it. So I painted the outside. A painting like Pond Life (1993) pictured what would be advertised in Canadian newspapers as a very contemporary and exclusive executive log home, but the style was still reminiscent of a homely old log house. Iron Hill (1991) had a house that reminded me of the houses I knew as a child growing up in Quebec. Then the Le Corbusier series happened by chance. Visiting the building in Briey, seeing the way it was situated there in the forest reminded me of much more modest buildings, but I ended up painting it as well, probably in quite a different way than I had painted other structures, because the setting is grimmer. It is close to Verdun, one of those quiet but very chilling places—many people died around there. When I drove across France for the first time, I drove through graveyard after graveyard after graveyard from the First World War. You see the German graveyard and then you see thousands of crosses for Canadian soldiers. Whereas other buildings had represented a family or maybe a person somehow, this building seemed to represent thousands of people. When I went to see the Le Corbusier building for the first time, I never dreamed that I would end up painting it. I went for a walk in the woods on one visit, and as I was walking back I suddenly saw the building anew. I had no desire to paint it on its own, but seeing it through the trees, that is when I found it striking.

Have teachers ever given you any good advice?

One teacher said, "You know, Peter, you don't have to go to the studio only to paint." It's good to look. Sometimes I spend a lot of time there just looking at things.

Painting pictures is often thought to be an insular activity, yet you have always balanced the solitude with a kind of sociability. In the mid-1990s Matthew Higgs, an artist and curator friend of yours, organized an early Jeremy Deller exhibition in your studio, and you were also involved in programming the Cubitt Street Gallery.

These activities counteract being on your own. I have always enjoyed being involved in other artists' work in some way. With Matthew Higgs I missed his Deller exhibition but I let him use my studio while I was away one summer. In places like Cubitt Street it was always good having a gallery, having activity. Something about it was more exciting. You were a bigger world than just yourself and your studio. Some artists, of course, need solitude. They need to be immune to this world, to be three hundred miles away from anything and on their own. Or else they have to have a room no one is allowed to enter. I have never been quite like that, although the room I paint in is private. While I don't mind people hovering about, I don't like to have people in my studio while I am painting. I find it very distracting. I have never had an assistant.

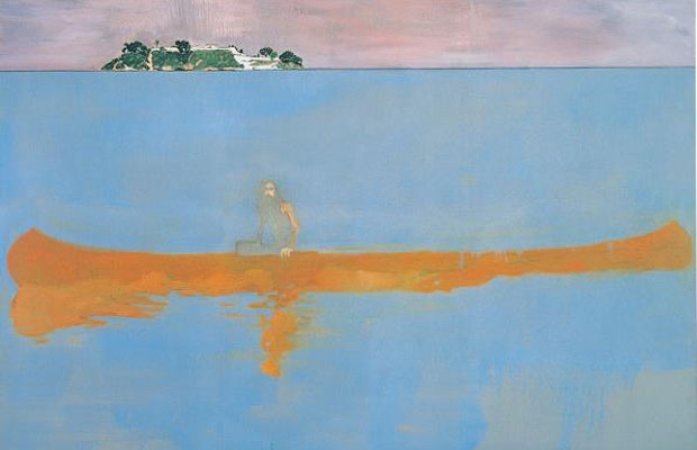

Peter Doig, "100 Years Ago," (2000), Image courtesy of Phaidon

Peter Doig, "100 Years Ago," (2000), Image courtesy of Phaidon

In the late 1990s your handling of paint changes. You move from the thick surfaces found in Blotter to the thin minimal washes of paintings such as 100 Years Ago (2000). Why?

I always try to escape my mannerisms. I repeat myself, and many artists repeat themselves, constantly and on purpose. As well, I am always trying to find a way of making something less complicated, more fluent, more fluid. It doesn't always work, and maybe that's why the paintings sometimes become much more built up. You can't just reinvent yourself as a Milton Avery-type painter, but maybe every painter wants to have the opportunity at some point. I don't want to become known as someone who paints thick paintings. I want to be less constricted by what I have become known for and see if the subject can still come through with a very light treatment, rather than a kind of heaviness. I used to become annoyed when people said they really liked my thick paintings. They fetishized the fact that the paint was fat, which is an absurd point of view. When I started making the ski-jumping paintings they were a way of escaping from the paintings that had this all-ver surgace that clogged up the image, a web of things you had to look through, whether snow or branches or whatever it was.

You are passionate about music. In the catalogue for 'Blizzard Seventy-seven';—Your 1988 exhibition at the Kunsthalle zu Kiel, the Kunsthalle Nurnberg and the Whitechapel Art Gallery—Matthew Higgs contributed an appendix entitled 'Peter Doig's Record Collection: A Project by Matthew Higgs'. In it he listed all the music in your studio categorized by support: CD, vinyl, cassette. Rock stars such as Gram Parsons, Berry Oakley, and Neil Young make appearances in your paintings. What is the relationship of your work to music?

I spend a lot of time alone in the studio, and I became obsessed by certain musicians' work and go through periods where I listen to nothing else for extended periods of time. Most people don't have ten hours a day to listen to music over and over and over again. I find with, say Neil Young, of course everybody has been listening to Neil Young, especially my generation, forever, but then I will hear a song or an album and I will go back and find other recordings of him. I will listen over and over, and inadvertently it becomes a kind of backdrop to the work. It is very different from making art about obsessions with musicians or popular figures. In the paintings it is more about taking a figure and having him stand in for something else. I like to think that these personages are not so much displaced as re-placed in the paintings.

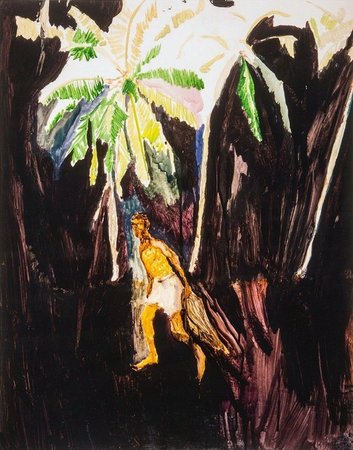

Peter Doig, "Untitled," 2006, Available for purchase on Artspace $4,000

Peter Doig, "Untitled," 2006, Available for purchase on Artspace $4,000

Artists often leave their place of birth and eventually migrate to major cities for the cultural and educational opportunities. Others arrive in the city only to leave in search of something more remote. I am thinking of Agnes Martin, who eventually ended up in Taos, New Mexico, or Donald Judd, who went to a small town in Texas. Why did you and your family leave London in 2002 for Port of Spain, Trinidad?

I guess I was looking for something else. I supposed that's why I left Canada and went to London. Coming to Port of Spain in 2002 as an invited artist in residence, I felt like I had arrived somewhere very special. I knew the place because I had lived here for five years as a child. I had left at the age of seven, but I still recognized parts of the city and found some of the sights, sounds and smells familiar. After completing the residency in 2002 and returning to my studio in London, I found that the paintings I made, even if the subjects were not exclusively about Trinidad, contained elements of being there. So I thought I would try to go and work there for a while. Initially, I came here to work on what became the "Metropolitan" exhibition. I spent the first two years working towards it but soon found myself wanting to remain here. I had the opportunity to live here as a child and wanted my own children to have the same experience. I am not sure how much longer I will stay, but at the moment it feels like the right place to be.

Where is your studio?

My studio is in a complex called Fernandes Industrial Centre.

The complex is a converted distillery?

It was an old rum factory, and the studio is where they used to store barrels of rum. When we lived in Trinidad in the 1960s my father made a painting that we always called The Rum Factory. It has always been on the wall in my parent's house When we lived here my father bought quite a few paintings by Trinidadian artists. The oil paintings I knew and grew up with in Canada were by Trinidadian artists. Strangely, when I came back to Trinidad five years ago, the house where I stayed was three minutes walk from the house I grew up in, and tech studio where I worked was in the same compound where my father had painted The Rum Factory. My father's painting is of a cooling tower—or something like that, a galvanized structure, almost like a silo—that is part of the Fernandes compound. I saw some old photographs in the archive there of this cooling tower, which has since been torn down. I remember my father making that painting.

You have a big studio.

It is a big studio, probably five thousand square feet, but I only use a very small portion of it. The main room was way too big to work in. I felt dwarfed. So I work in a smaller room of about seven hundred square feet.

While you were in Canada you were making paintings of London and about London. When you came back to London your paintings looked towards Canada and France—I am thinking of the Don Valley Parkway in the numerous versions of Country Rock or the Le Corbusier building in the Concrete Cabin series. However, with Grande Riviere (2003), the painting of the old white racehorse, along with the Pelican series with the man walking along a beach, there seems for the first time to be a strong connection to the place you are living and the place you are painting.

Well, I started the Pelican paintings in London, and it has to be said that for the most part the paintings I made in the last few years in Trinidad were all based, initially, on subjects that came from outside Trinidad. Maybe I was painting Trinidad by proxy. But maybe you are always painting where you are even if you are actually painting somewhere else. Yes, certain paintings crept up on me, and I made a few paintings and then a few more paintings of Trinidad. But I want to avoid that. A lot of the recent paintings were based on postcards I found in a junk shop in London, mostly uncaptioned pictures of southern India. They could, however, pass for Trinidad.

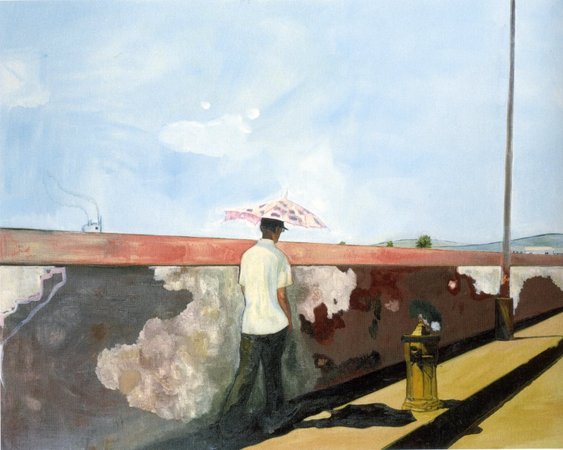

Peter Doig, "Lapeyrouse Wall," (2004), Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Peter Doig, "Lapeyrouse Wall," (2004), Image courtesy of Wikipedia

The reproductions of your work in certain publications emphasize your process—for example the "Metropolitain" catolog contains numerous versions of Lapeyrouse Wall (2004). The approach, making versions, connects you to your precursors. But you are also offering your audience a view on to your process. What is going on in your mind?

With the different versions of Lapeyrouse Wall I was trying to work out how best to define the subject, how to do justice to it—for instance, how to get the actual gait of the man's walk. The first painting Lapeyrouse P.O.S. Pink Umbrella (2003), was something I did one afternoon quite quickly. I found the figure in a photograph I had taken, and I just drew it up. Somehow it stuck with me. I moved on from that and made another version, Cemetary Wall (2003), and then I felt more and more drawn to the image. Next I enlarged the figure (this is on the back cover of the 'Metropolitain' catalogue) by almost two-thirds. The enlargement is of a little pencil drawing, a somewhat Lowryesque drawing, and it became too clumpy and cartoon-like when it was larger. So to make the big painting I had to go back to the photograph. Although there are cartoon elements in Lapeyrouse Wall, I didn't want it to look like a cartoon. I like the drifting nature of the figure and the fact the wall conceals the bigget cemetery in Port of Spain. I had just seen the film Tokyo Story (1953) by Ozu and had been struck by its measured stillness, and I wanted to make a painting that captured that. Lapeyrouse Wall is an odd painting for me to have made, though. It possesses a type of realism that I never thought I would enter into, something that looks Edward Hopper-like in parts. It was somewhere I never knew I was going to go, but I found myself there.

RELATED ARTICLES

Six Artworks Worth Investing in this August

The YBAs Still Rule at London's Contemporary Auctions