It may come as a surprise that Rashid Johnson’s show “Anxious Men,” on view through December 20th at the Drawing Center, features some of the artist’s first forays into figuration outside of his photographs and films. Anyone who delves deeply into the African-American experience can’t help but grapple with questions of representation and racialized bodies, and Johnson has confronted these issues head on with a sensitivity and wit that have made him one of the most sought-after artists of his generation. Even so, he’s moved away from the figurative photographic work that brought him art world renown in the wake of theStudio Museum in Harlem’s pivotal 2001 group show “Freestyle.” His recent output seems to shift the conversation towards more conceptual terrain. Many works in his 2012 solo show “Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks” at MCA Chicago saw the body conspicuously absent, displaced by symbolically-loaded materials like shea butter, potted plants, mirrors, and Persian rugs along with books by Black Power thinkers like Amiri Baraka.

The black soap and wax compositions in “Anxious Men” can be read as an attempt to bridge the gap between these two aspects of his career. As Johnson suggests in this conversation with Artspace’sDylan Kerr (conducted on the occasion of the release of Phaidon’s new book Body of Art), the ways in which the body is used, rather than represented, in art can be powerfully illuminating.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon'sBody of Artand buy the book.

What are some artists that have been influential on your thinking about the place of the body in art?

Three names come to mind. The first is Wolfgang Laib, who often used his body to spread his pollen through spaces. His use of materials has a lot in common with things that I’ve thought about over the last few years. Another artist is David Hammons, for his use of his body in films and performances like Phat Free or Bliz-aard Ball Sale and probably even more directly through his body prints. The third artist who comes to mind, perhaps unexpectedly, is Andy Goldsworthy. Andy makes me think about the positions that he puts his body in while making sculptures in space.

When I think about the body in art as an artist practitioner, I think more about the movement of the artist than I do the representation of the body. I think about how the body moves or is forced into action as an artwork is being made. I don’t really think about traditional easel painting, because I think that those movements are so controlled, so micro, so process-driven compared to other ways of making art—the painter with a brush representing the body seems more like a psychological study than a physical act. That doesn’t mean I lack appreciation for that way of working, of course, but I’m more interested in the ways a practitioner has to move their body physically in relationship to an artwork.

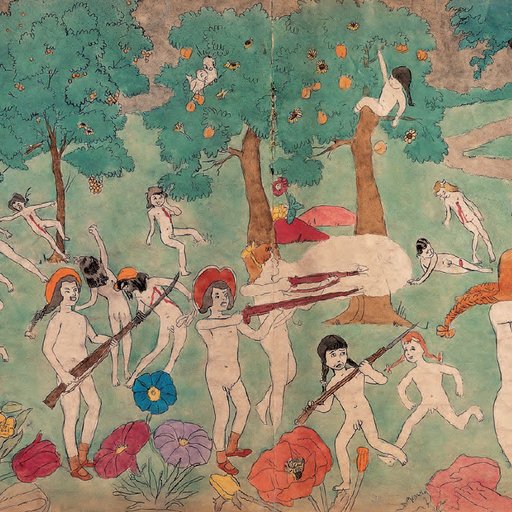

I guess Hammons’s body prints would split the baby—they obviously function as a representation of the body, but they also call to mind the force that the artist’s body needs to go through to represent itself in the most direct sense.

America The Beautiful by David Hammons (1968)

America The Beautiful by David Hammons (1968)

It seems to me that is one of the crucial turns in 20th century art—refocusing attention on the physical act of art making rather than the end product exclusively.

Definitely—this is a very contemporary perspective. The idea is really born post-Pollock, where the body becomes a tool. Pollock’s body essentially functions as a brush. From my perspective in art as an artist, the time after that Abstract Expressionist period is when the principles that I continue to adhere to were born. You have the psychological drama of the body as well as the tension of interacting with material—it becomes the instrument for how that material is distributed, but also how the ideas around that material are distributed. The body is kind of forced into whatever position it needs to be in to allow that representation to become accessible.

How does a Land Artist like Andy Goldsworthy fit into this paradigm?

For most of us that are familiar with Andy’s work, one of the go-tos is the film Rivers and Tides. What you really learn about his practice through that film is that his body is subject to conditions outside of itself while he’s making art. He’s making work with ice, so you have take into account that he’s outside, and it’s fucking freezing cold. If he’s working in a stream, he’s soaking wet. He’s manipulating these materials that are, more often than not, particularly cooperative. The idea for me is that the artist doesn’t necessarily have to be in the cozy condition in order to make art. We usually think about the more traditional practice of an artist in their studio. We might think that they’re starving, but we sure as hell don’t think that they’re wet or freezing or physically uncomfortable.

Balanced ice column, Helbeck Craggs, Cumbria, 5 January 1985, by Andy Goldsworthy (1985)

Balanced ice column, Helbeck Craggs, Cumbria, 5 January 1985, by Andy Goldsworthy (1985)

It’s interesting to think about how that physical state affects the decisions that we make and what positions we’re willing to put ourselves in when making something—it’s a different perspective on the body in art that just sort of jumped out at me when I started thinking about it. What is Goldsworthy willing to subject his body to in order to fulfill whatever his expectations or goals are for an artwork?

For me, I’m often making work with heavier materials, so I’m really empathetic to the idea of the artist having to physically lift or otherwise participate with the materials before the work is installed—before it can be witnessed. More often than not, we come to art as a witness. We usually don’t take into account the conditions under which these objects were made—nor can we, really. In a lot of ways art is intended to suspend disbelief, so maybe we’re not even supposed to engage with that aspect, but I do. “What did it take to make this?” is one of the questions I ask myself when I look at an artwork. I’m interested in how it came to be as well as its goal or conceptual framework.

David Hammons strikes me another artist who, at least in some of his work, points to the labor required to realize a piece.

Absolutely. I like to bear witness to that kind of labor. In another way, I think an artist like William Pope.L fits into that formulation.

Totally. I’d say that he foregrounds it.

I think about something like The Great White Way, where the body becomes this vehicle for dress-up while also talking about the struggle that it takes to get from A to B when you’ve made a decision to do that in a way that’s inherently complex.

I guess that the performance of making art is really the most salient aspect of all the artists that I’m talking about. There’s something inherently performative in the way that they proceed, but the final artwork is not always a performance per se.

Wolfgang Laib installing Pollen From Hazelnut at MoMA, 2013

Wolfgang Laib installing Pollen From Hazelnut at MoMA, 2013

I really see this in Laib’s work as well—the end result is just a room full of pollen, but the piece starts to open up as you start to think about what it took to get there.

Absolutely. You can see how his body moved in a circle—how did that cyclical movement become what we’re left with? For him, it’s also about the gathering of the material. Laib is the one who collects this pollen—it’s not like he sent out an assistant to buy it from the store. He puts himself in a position to acquire the materials, with that acquisition being, in some ways, part of the artwork and part of what his body had to negotiate for the artwork to be born and acceptable to an audience.

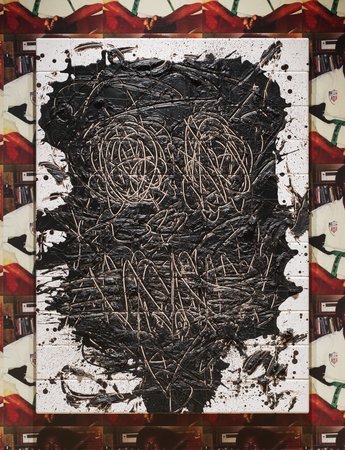

Do you see any of these ideas we’ve been talking about at work in your show at the Drawing Center?

I do. I think the way I would make that marriage is through process and how I make those artworks. There’s something about those pieces that is very much about the anxiety of movement. You’re dealing with a material that has to be negotiated in a short period of time. The black soap and wax is melted down into a liquid, and after it’s poured you have between five and ten minutes to manipulate it. It’s a very short period of time, and when you’re dealing with this kind of time constraint your body has to engage with the material with a certain speed in order to be able to manipulate to the place that I like those works to get to. It’s not as if I can think about other things and come back to it—my body is committed to moving in that space during that period of time.

I think this process definitely has a relationship to Hammons’s body prints. Once your body is covered in that grease, you lay down on the paper and it’s done. There’s no opportunity to manipulate it further. It’s either successful or it’s a failed object. I think there’s a similar thing being negotiated by an artist like Laib, too. He’s gathered the material and he’s put it into the space in a certain way, but I imagine it is what it is once it hits the ground. His use of beeswax on some of his sculptures seems to be doing the same kind of thing.

Throughout my body of work, I’ve been concerned with how you can manipulate something while moving around it. I don't ever approach an artwork from a specific direction. I generally don’t stand in front of an artwork and work from one position—I often work on the floor, so I’m approaching it from several different directions. It’s not dissimilar from Laib approaching his circles, or Hammons approaching the paper that he’s going to put his body on. He’s coming from multiple angles, because he’s trying to figure out how to attack it.

They always call the boxing ring “the squared circle,” and you can compare this process to a fight. If you get in a fight and just stand in one place in front of the person you’re fighting, that wouldn’t necessarily work. This could be applied to anything. Think about sex—you have to move. You can’t just stay in one place.

In either metaphor, you’re probably not going to be successful.

[Laughs.] Exactly. This is how I try to think about approaching artworks, and that inherently takes the negotiation of where you are as opposed to the flatter concern of where the object is.

So much of my work plays with these ideas. I recently reproduced an Allan Kaprow Happening or sculpture event for FIAC, where I built a wall based on his piece Sweet Wall that he built in 1970 in Berlin. I built a wall out of shea butter in front of the Petit Palais in Paris, so mine is called Shea Wall. I did it in collaboration with the Kaprow estate, so it was a really interesting opportunity to pay homage to and work through an idea of an artist I have a tremendous amount of respect for. The physical nature of building that wall as both a performance and a discussion of labor and all the things that come with those concerns. It speaks pretty directly to a lot of the things that we just talked about.

Installation shot of Shea Wall, 2015. Photo: Emilie Pillot

Installation shot of Shea Wall, 2015. Photo: Emilie Pillot

How did this Happening come about? It’s a real melding of the worlds.

I share a gallery [Hauser & Wirth] with the Kaprow estate. I’ve seen them allow other artists to work with some of his performances in the past—they’re pretty good about granting the agency to explore his works. When I came across Sweet Wall, I started thinking about what wall building means in the present context. Kaprow was obviously referring to the Berlin Wall in 1970, but when you think about what’s happening today in terms of conversations about walls and accessibility. If you think about Trump’s "platform" of building a giant wall, or what’s happening in Europe with Syrian refugees—it’s not necessarily a discussion of wall building, but the discussion of access and borders. I was looking at what all this means to us right now, so it felt like an appropriate time to grant myself the opportunity to discuss that. Luckily, the circumstances were such that it was a possibility for me, so I just ran with it.