“Want to write something from the perspective of an artist on view at a fair, maybe?” inquires Andrew Goldstein, the editorial Svengali at Artspace Magazine. “I want to cover the art world from every perspective.”

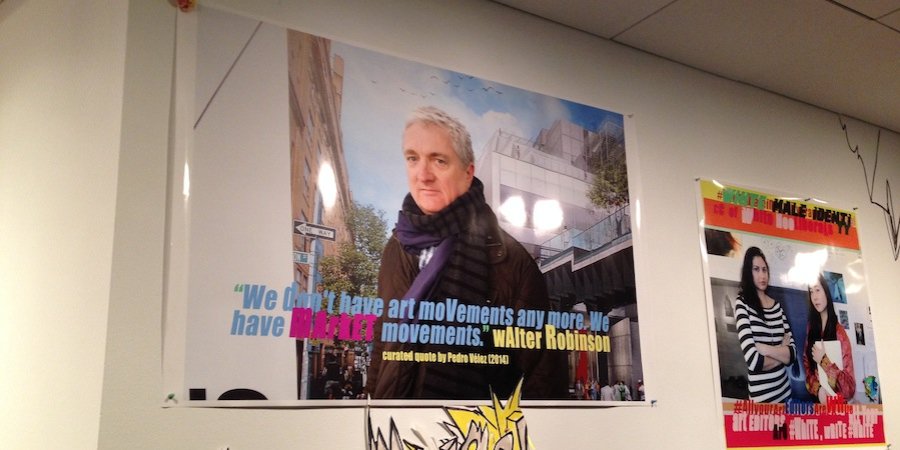

I’m all for that! I can tell you, for instance, what it’s like to have the Puerto Rican artist and critic Pedro Vélez use a large photograph of me in his Whitney Biennial installation. A barbed look at white art critics—much of this year’s biennial is art-about-the-art-world—Velez’s vinyl banner with my picture and a quote (“We don’t have art movements any more, we have market movements”) is right across from the elevator on the basement floor, perfectly located between the café and the bathrooms.

What do I think of it? I love it. He does the work, I get the attention!

As an artist, I’m ashamed to say, I haven’t always been that comfortable with attention. Several years ago I was at a collector’s house in Old San Juan, where the walls were filled with emblematic works by hot artists like Peter Doig, Elizabeth Peyton, and, of course, me. I wasn’t altogether at ease. My stuff, from both by “romances” and “spin paintings” series, looked weirdly out of place, and seemed to shift and warp on the walls like a scene from a bad LSD trip. Ugh, anxiety!

Among the art celebrities on hand was Jonathan Meese, a young German artist known for madcap performances and installations. Very comfortable in the limelight, Meese has a high-pitched voice and infectious laugh, and with his long dark hair and beard looks like a slightly demented Jesus. He spotted his own painting, a tall canvas covered with expressionistic marks and lumps. Rushing up to it, Meese practically embraced the picture, caressing its surface and exclaiming, “You hung my painting, there it is, I love it, thank you, thank you!”

Now that’s the way an artist should greet the public display of his or her work.

Walter Robinson's My Love Is Violent (2011)

Walter Robinson's My Love Is Violent (2011)

I repeat this story on the occasion of the Spring/Break Art Show, running March 6th through 9th, a sprawling anti-fair of several dozen curated art installations organized by artists, critics, curators and art dealers and spread through a four-story former school building at 233 Mott Street in Little Italy. A couple of months ago, the founders of the three-year-old fair, Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori, had visited my Long Island City studio and selected a bunch of my paintings for a solo exhibition. Spring/Break's overall theme is "public/private."

When I asked Ambre about arranging the pick-up of the paintings, she said, "How about Friday? I'll have my parents' car." It’s that kind of show, filled with raw DIY enthusiasm that prompted Chelsea art dealer Doug Walla of Kent Gallery to email a note: "Loved the energy and the honesty of the event. VERY refreshing."

During the Spring/Break vernissage, I was in no hurry to check out my own rooms on the third floor, and instead lingered by the entrance, greeting friends. They always ask you, “How are you doing?” At an opening, you can get this question over and over, and I’ve always felt pressed to come up with a different answer each time. In Spring/Break’s first gallery was a small artwork that provided ready answers, a digital LED read-out aggregating tweets beginning with the words "I need"—all ready answers to the question. How am I? "I need a haircut" and "I need to get my mind off things" and "I need retail therapy pronto." The piece, by Jean-Baptiste Michel, is a gem, and bargain-priced at $1,700, I think he said.

Accepting compliments about their work can be a problem for some artists, strange as it might seem. Back in the early ‘80s, the thought of many such encounters discomfited me so much that at the opening for a show at Metro Pictures I set up a table with Tanqueray and olives so that I could respond to praise by asking instead, "Hi, can I make you a Martini?" I was surprised when everyone got drunk.  Golden Hooligan (2014)

Golden Hooligan (2014)

The very first VIP I ran into at Spring/Break was none other than former Los Angeles MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch, who I first met in the early '70s, when he was tending the front desk at John Weber Gallery in the 420 West Broadway building in SoHo. He had an unusually positive outlook back then, and was positive this time around, too, saying that he had a pair of my stencil prints, which I had made back in 1980, at his house in Los Angeles. I returned the favor, complimenting him on his suit, which was done in a golden thick-wale corduroy. “It’s artist’s suit,” he said. “Modigliani had one like this.”

The fun part of a vernissage, at least for me, is swapping wisecracks with your pals. Admission to Spring/Break is $5, and the artist and filmmaker Eric Mitchell, who splits his time between Paris and a tenement apartment on East 3rd Street, said he told the young women at the door that he was Larry Gagosian and they let him in for free. Though Mitchell speaks with a pronounced French accent, he also claimed to be Flemish and a hockey player, and showed us an iPhone video of himself gliding across a frozen lake.

My 18 paintings in the show (also bargain-priced at $2,500-$9,000) are expertly installed in two smallish rooms that were certainly once offices rather than classrooms, with buff walls aging to yellow and dark blue-green carpet on the floor. The sculptor Tom Otterness, who was a primary mover of the 1980 "Times Square Show" certainly knows the art-in-old-buildings routine, went right to the carpet, praising me for snagging the space with the spongy floor. “Did you have to pay extra for carpet?” he asked.

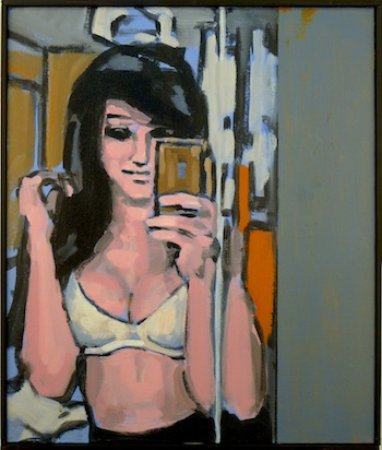

Backpage Chicago (Self) (2012)

Backpage Chicago (Self) (2012)

The worst part is watching people come in, glance around, and leave. “At least they come in,” said artist Robert Yoder, in town from Seattle, where he runs the Season gallery. He’s got a booth full of ceramics and ink drawings on paper by Elisabeth Kley over at the Volta art fair, only a few blocks away from Spring/Break.

The best part came when the curators visited my studio and winnowed out works on the “public/private” theme. They looked at my pictures of passion and desire—people kissing, in my own shorthand—and saw lovers interrupted, conspirators uncovered, and spies on the run. They saw things, obvious things, that I had overlooked. That’s my takeaway. Maybe curators aren’t so dumb after all.

Walter Robinson is an artist and art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). His work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, Dorian Grey, and other galleries. He can be reached at walter@artspace.com. Click here to read his previous See Here column on Artspace.