They love, love, love Isa Genzken over at the Museum of Modern Art, where the artist’s first major American museum survey remains on view through March 10, before traveling to museums in Chicago and Dallas. The 65-year-old Berlin-based German sculptor, whose 150 works fill 10 open-plan galleries on the museum’s sixth floor, is “one of the most important artists of our time,” writes MoMA curator Sabine Bretwieser in what may at first appear to be ordinary curatorial hyperbole.

But wait. According to another MoMA curator, Laura Hoptman, Genzken has “forged an entirely new sculptural language” that has “helped to define a period in the visual culture of Germany as well as in contemporary art internationally.” Though relatively under-known to New York, Genzken does have a global following, and has been included in dOCUMENTA (three times), the Istanbul Biennial, the Carnegie International, and the German pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

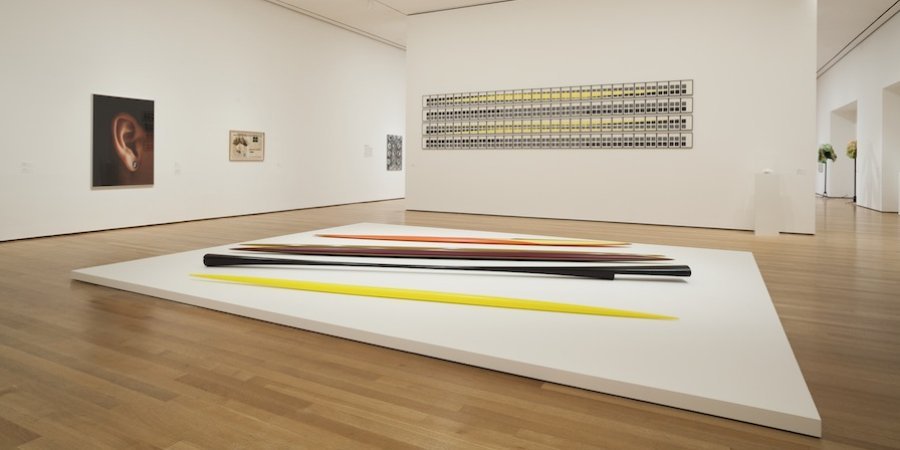

So what is the stuff? Large fabricated knitting-needle-like forms that sit on the floor; window frames and radios cast from rough-hewn concrete; skyscraper-ish monoliths that are “portraits” of fellow artists like Dan Graham and Wolfgang Tillmans; and—most of all—colorful assemblages of bashed-up hardware-store flotsam and odds and ends that might have come from Bed, Bath & Beyond.

You get the feeling that Genzken is an artist who shops for stuff, and then piles it up like a crazy person.

The sensibility doesn’t seem that unusual on first glance, however, and a tour of the museum’s collection finds a few notable precedents: Marcel Duchamp's In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915), the snow shovel he hung from the ceiling like a prescient, found-object version of a Calder mobile, is on MoMA’s fifth floor; on three, in the museum’s tribute to dealer Ileana Sonnabend, is Robert Rauschenberg’s Canyon (1959), the combine bearing a stuffed bald eagle that, according to the art historian Thomas Crow, is an emblem melding postwar American imperium with the homoerotic myth of Zeus and Ganymede (who is represented by a black-and-white photo of the artist’s young son). (The bird, now rather the worse for wear, today also symbolizes bureaucratic ineptitude, since it has ended up in the museum after the IRS valued the work at $85 million for estate tax purposes, even though the eagle’s status as a protected species prevents it from being legally sold in the United States.) One immediately thinks of Genzken-comparable pieces by the likes of Judy Pfaff, Frank Stella, Jessica Stockholder, or even John Chamberlain, but for one reason or another they aren’t to be found in the Modern.

Genzken’s work lends itself to similar interpretations, though her things reveal a sensibility that I think of as “schizoconsumerist”—deeply immersed in spectacular commodity culture, and clearly distressed by it. This reading is influenced by the artist’s biography: on the occasion of this retrospective, Der Spiegel reported something that art-world insiders already know, which is that the artist is both manic-depressive and “constantly in treatment” for alcohol dependency.

The academic Benjamin Buchloh—Genzken’s teacher and one of her romantic liaisons (she was later married to Gerhard Richter)—is quoted in the catalogue suggesting that the artist was brought to "brink of psychosis" through a "terror of mass consumption." Presumably this quality of mental trauma, which has an echo of “Anti-Oedipus: Schizophrenia and Capitalism,” Deleuze & Guattari’s densely metaphorical tome from the 1970s, is a virtue; certainly in “Anti-Oedipus” the “unstable subjectivity” of schizophrenia is viewed as inventive, expansive, and anti-bureaucratic.

Genzken’s work is definitely psychologically expressive, perhaps to a greater degree than her aforementioned colleagues. An early example is My Brain (1984), a shrunken, bleached blob modeled of plaster and studio sweepings, with a thin wire antenna reaching feebly upward as if in search for the kind of divine rays that tormented Freud’s famous schizophrenic patient, Daniel Paul Schreber. Similarly, a row of the cast-concrete portable radios—but with real antennas attached—suggest an effort to clamp down on the endlessly talking machine, or, alternately, manifestations of Deleuze & Guattari’s “body without organs,” their phrase for a notional ur-consciousness transited by vectors of desire.

Large X-rays from 1991 of Genzken herself laughing, smoking, and singing also raise questions of the reality of the self: What’s inside my head, anyway? Is it me or what? A tale from the artist’s student days relates how, when given a drawing assignment, she instead crumpled the paper and threw it to the floor, for once suggesting that a familiar avant-garde motif, the rebellion against conventions, might also signal a deeper rejection of the self.

The exhibition opens with a sprawling display of more than a dozen mannequins, oddly dressed in all kinds of motley, all part of a new collective work called Actors from 2013. Mannequins are of course hollow inside, and Genzken has dressed hers with considerable psychic abandon. Many wear Halloween masks, a few show signs of being connected to some absent machine, others wear leather fetish gear, a couple have chrome apparatuses on their heads that might protect against alien transmissions, and then there are some wearing leis as if being welcomed into the world of the living. A pitch-black mannequin of a child is accompanied by two white hula hoops and a stuffed black monkey, which sits on the boy’s shoulder as if giving him a kiss or whispering in his ear.

Actors is a work that aligns the artist’s method with ordinary shopping, as does Gay Baby (1997), an installation of a group of "clearly anthropomorphic" assemblages of kitchen equipment, hanging from the ceiling, that "resemble shiny robotic puppets," in Hoptman’s words. The Gay Babies, though, have clearly been smashed and bent, destroyed, not unlike Light (Ground Zero) (2008), a standing assemblage of chrome-plated Ikea junk that could easily pass as a 21st-century David Smith totem. Somehow, it’s easy to imagine shopping as a psychotic activity, the dark side of the “newness” that Jeff Koons celebrated with his 1980s vacuum-cleaner sculptures.

I don’t know whether Genzken’s work really plays as an attack on consumerism, or should rather be seen as a lyrical reaction to the world as an irrational, destructive system. I do like the way that her assemblages turn the spectator into something of a trash-picker, whose abject enterprise involves the careful parsing of discards and rejects. And I like the way that Genzken’s show at the Museum of Modern Art, like recent blockbuster exhibitions of Yayoi Kusama and Mike Kelley, constitutes the art world as a kind of asylum, in both senses of the word. Art’s eternal claim on the irrational is a truism worth remembering, especially in a milieu ostensibly so rationalist in its self-regard.

Walter Robinson is an artist and art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). His work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, Dorian Grey, and other galleries. He can be reached at walter@artspace.com. Click here to read his previous See Here column on Artspace.