It was like a smack in the face, seeing the dozen or so life-casts by John Ahearn in his recent show, "Works from Dawson Street and Walton Avenue," at Alexander and Bonin in Manhattan's Chelsea gallery district. Already more than a quarter century old, these painted plaster portraits—they depict the artist's friends and neighbors in the Spanish-speaking barrio in the South Bronx, where he lived and worked for many years (he's now in Spanish Harlem)—still seem uncommonly animated. Perhaps the jolt comes from their being so definitely "other," different yet familiar, somehow making invisible social boundaries suddenly palpable.

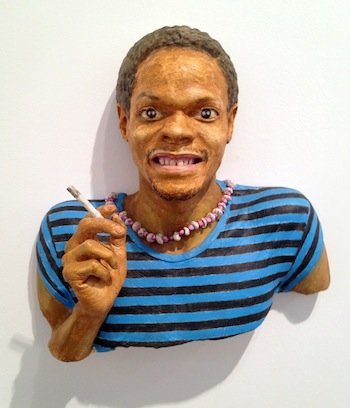

Ahearn’s modest busts are marked by sentiment, largely thanks to their sensitive, gestural coloring—surely at least some Roman or Greek marbles were once painted in this fashion. Freddy with Cigarette (1989) shows an enthusiastic young man in a blue striped shirt and a coral necklace, bursting with life. Titi (ca. 1985) is a heavyset dark-skinned woman who leans out of a tenement window, not unlike a ghetto Mona Lisa. The work had been installed on the side of a Bronx building where it was threatened first by fire and then by urban renewal, until the artist was able to rescue her.

John Ahearn, "Burnt Titi," circa 1985. Alexander and Bonin

John Ahearn, "Burnt Titi," circa 1985. Alexander and Bonin

Many of the works embody an implied narrative. The subjects are real people, after all, whose identity is elaborated by everyday anecdote. Ello Ree (1989) has a moody nobility, befitting a gaunt grandmother who wears a becoming white dressing gown, her hands twisted by arthritis and her neck scarred by a fire. Back then she was raising her two granddaughters; now grown, the women took the opportunity to come down and visit the exhibition one Saturday, their own kids in tow.

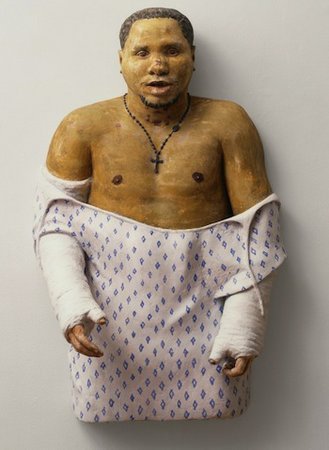

A real-life picaresque is present in Lazaro (1991), which depicts a young Latino in a hospital gown, with a glazed look in his eyes and two broken arms in plaster casts. According to the artist's brother, Wild Style director Charlie Ahearn, Lazaro was a neighbor who did minor burglary to support a drug habit, and ended up in the emergency room after an unsuccessful attempt to cross an air shaft on a makeshift plank walkway. Lazaro is a classic, whether he knows it or not.

John Ahearn, "Lazaro," 1991. Alexander and Bonin

John Ahearn, "Lazaro," 1991. Alexander and Bonin

A portrait has a real, living person at its center, as if to make the artwork itself into a living being, with the potential to be immediately legible, emotionally and culturally. Chuck Close portrays the most famous and successful contemporary artists, appropriately larger than life, arguably a vocational hazard. Ahearn's portraits depict ordinary poor people, at ordinary size, but they are given a certain nobility all the same, and as such can be considered emblematic of progressive ideals and democratic hope. It's a little romanticizing, this reading of Ahearn's works, but unavoidable, for they are steeped in "class," that is, the class of people who are poor, whose image is a rarity in the mainstream avant-garde these days, for all its academic politicizing. I remember the New Museum's 2009 "Younger Than Jesus" show, a motley collection of new art by 50 young artists from around the world, where among all the unconventional strangeness the simple, black-and-white photographs by LaToya Ruby Frazier stood out because of that same subject matter.

Class-consciousness is pretty much absent at the New Museum currently, despite that fact that the Polish artist Pawel Althamer has filled one floor with life-sized plastic golems purporting to be portraits of ordinary Venetians. Done in monochromatic gray, with masklike faces (digitally molded, one would hope) and bodies indicated by a kind of sculptural shorthand of hardened mummy-wrappings, Althamer's figures suggest nothing so much as the self-aware androids of FX science fictions like I, Robot. The works are apparently popular, and the artist should certainly be welcomed on the occasion of his New York show, but “The Venetians” constitutes a bureaucratic life-view: people are barely distinguished and interchangeable. Perhaps that’s his point.

John Ahearn, "Freddy with Cigarette," 1989. Alexander and Bonin

John Ahearn, "Freddy with Cigarette," 1989. Alexander and Bonin

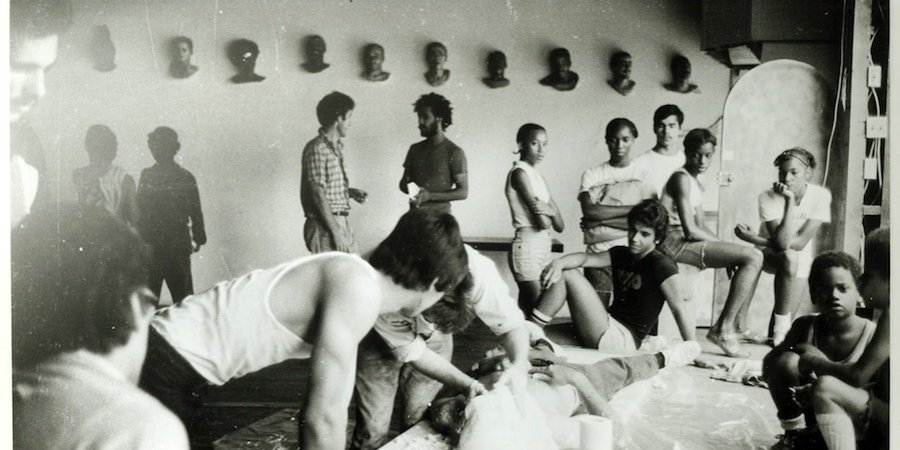

Ahearn made his portraits of his neighbors in the Bronx while involved with Collaborative Projects, a group of artists who came together in the late 1970s to take advantage of the then-ample government funding for "artists' spaces" (the money was one reason, anyway). Possessed by a populist iconoclasm, many of these artists took themselves to the fringes of the established art scenes in SoHo, on 59th Street and on Madison Avenue, notably via Colab-funded affiliated projects that included Fashion Moda in the South Bronx, ABC No Rio on the Lower East Side, the New Cinema in the East Village, and of course the Times Square Show. The group even went so far as to pull out of a scheduled exhibition at the New Museum, a decision that treated the museum’s young curators with rude disregard in the interests of some issues of artistic integrity and independence that are now forgotten.

Ahearn, for his part, relates that he was a landscape painter in search of new vistas when he arrived at Fashion Moda in the Bronx in 1979 and set up a casting studio in the short-lived storefront. He almost immediately met and partnered with a young man from the neighborhood, Rigoberto Torres, who had been working in his uncle’s statuary factory; their first joint studio was set up on Walton Avenue, a storefront in the building where Rigoberto lived with his parents.

The works that these two artists make are not glamorous, and are hardly fashionable (one of my many regrets is that I passed up a chance to buy one of Ahearn’s works at a massive discount in 2012, when Chico sold at Skinner in Boston for just over $1,400; at the gallery now they can be had for around $15,000, I believe). These sculptures are so ordinary, in fact, that they are timeless, which makes them momentous, and emblematic of the esthetics of everyday life. Their message is profound yet simple, about what artists should do, and what we all should do. Just live.

Walter Robinson is an artist and art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). His work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, Dorian Grey, and other galleries. He can be reached at walter@artspace.com. Click here to read his previous See Here column on Artspace.