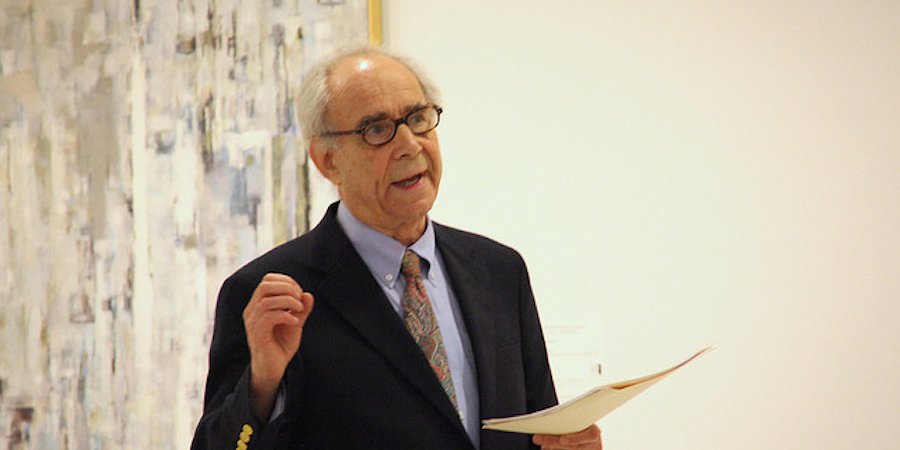

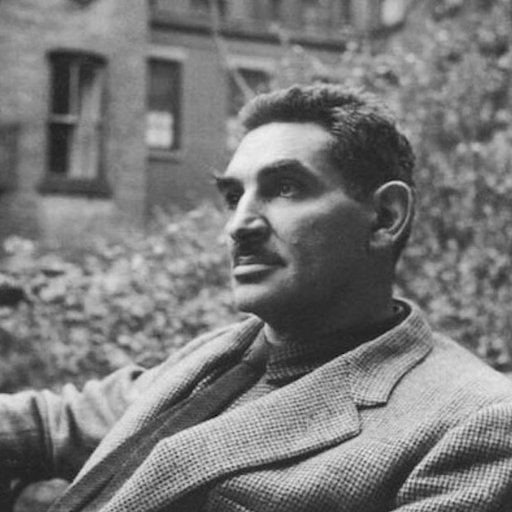

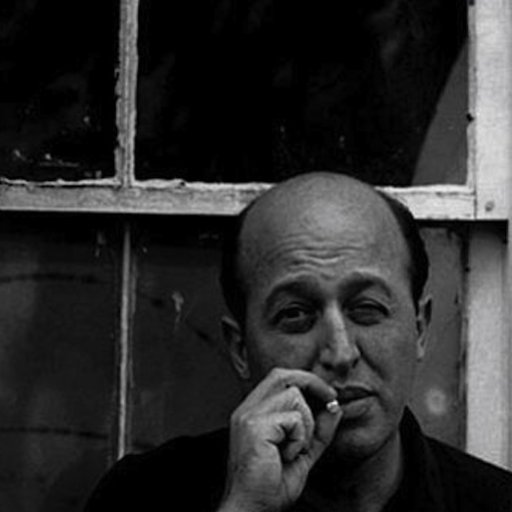

Irving Sandler is an artists’ art historian. In contrast to other prominent midcentury art critics—like the New York Times’s John Canaday, who warned him against fraternizing with artists for fear of impairing his critical distance—Sandler purposefully immersed himself in his subjects' milieu, first in his days as a young reviewer for Artnews and later as an art historian. Summing up his writing career in 2006, Sandler proudly wrote: “The thread that runs through my writing is a concern for the intentions, visions, and experiences of artists.”

What follows is a brief look at Sandler’s career, and what makes him tick.

WHAT DID HE DO?

Irving Sandler considers his lifework to be his four-volume history of the art of his time, which he began writing in the 1950s and carried through to the early 1990s. The first book was to be titled A History of Abstract Expressionism, until the Book of the Month Club requested 10,000 copies from his publisher—on the condition that it had a “livelier title.” Thus “A History” became The Triumph of American Painting. And the tome is not as dogmatic as its title implies. Sandler’s goal has never been to stake out his own stance on new art but rather, as once said, citing Woodrow Wilson, “to reflect ‘the sympathy of a man who stands in the midst and see like one within, not like one without, like a native, not like an alien.”

The Triumph of American Painting is a work of participatory, living historical activity. Most of his research was artist-based, a fact he makes clear in the book’s acknowledgements: “My first debt is to those artists who generously submitted to interviews, engaged willingly in lengthy discussions, and searched hard for answers to specific questions.” It's not unusual for an art historian or critic to mingle with artists; it is unusual for an art historian to turn those interactions and the firsthand knowledge that results into the basis for scholarship. This was Sandler’s gift. As he explained, it allowed him to deal “with artists’ intentions precisely in order to capture the embryonic period in the development of their styles—before they were assimilated into art history.” (Sandler admits he did not know the artists of the remaining three volumes as well as he did the artists in Triumph, since “given the number, it was not feasible.”)

In the Abstract Expressionist period of the 1950s, when the principle artists made up a small community in New York, Sandler ingratiated himself with them by showing up at their hangouts—first the Cedar Street Tavern then the Club on Eighth Street—for more socializing and discussions. He befriended artist great and minor, and was purposefully “inclusive,” even in his writing, but he came to develop his own personal "pantheon" of favorites. These included: Mark Rothko, Philip Guston (“Philip would say again and again—as if he had never said it before—that everything in a work of his had to be ‘felt’”), Franz Kline (he “held court at the Cedar Street Tavern almost every night after ten”), David Smith, Tony Smith, Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Hans Hofman (“I always admired Hans’ painting and believe that certain of his pictures—Lava and Agrigento come to mind—must be numbered among the greatest abstract expressionist canvases”), Willem de Kooning, and Clyfford Still (“as a de Kooning man, it took me time to appreciate Still’s innovation”). Sandler’s “pals” included: Alex Katz (they’re still friends today), Philip Pearlstein, Al Held, Mark di Suvero.

As an art critic, Sandler did not proclaim works to be good or bad in the ex cathedra manner of Clement Greenberg. Instead, he would ask: “What is an artist’s vision, how is it expressed, and is the work a singular achievement?” Greenberg chastised him for his method in a letter, writing, “you don’t mix enough criticism with the description & narration & explication. No artist—no public figure—should be taken at his own word. In the end you do yourself a disservice by that acceptance, however much it wards off what’s called controversy. You have your opinions: why not express them?”

For his part, Sandler felt that too much criticism and art history were written for the writers’ sakes—not truly for the art, or the artists, or even, really, the readers. It was against this type of “self-promotion” and the notion of “writers focused on ideas about art rather than on actual works” than he purposefully sought to place the artists’ thoughts before his own. Although he found much of the art criticism of the 1950s and '60s to be lacking—or, in the case of Clement Greenberg, having “undue influence”—he did write that “If I had the choice to be someone else, it would be Meyer [Schapiro].”

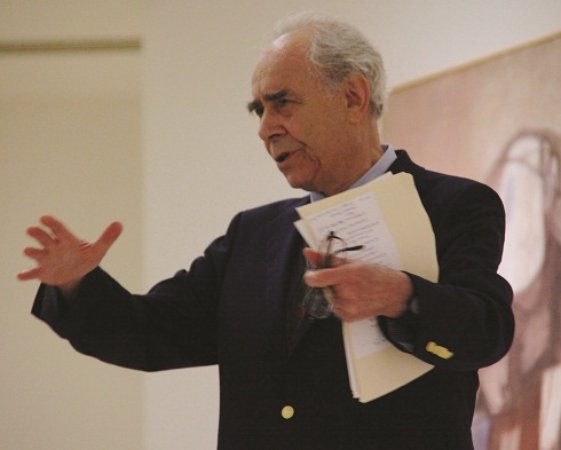

Today Sandler continues to monitor the art of his time as an art-historian-about-town, writing his books, popping up at gallery openings, and even curating the occasional show, as he did at the Cue Art Foundation in 2010 with Robert Storr. As one article began: “Is there anyone in our Manhattan art world who does not know Irving Sandler?”

BONUS FACTS

– The first work he “really saw” and which “changed his life completely” was Franz Klein’s Chief (1950) at MoMA in 1952.

– Sandler met Mark di Suvero in 1959 when he was looking for an artist in need of work to paint his apartment. Mark di Suvero got $75 and lifelong champion for his efforts.

– He managed the artists’ cooperative Tanager Gallery on 10th Street from 1956 to 1959.

– Sandler became the administrator of the famed artist discussion haven the Club in 1956 (until 1962), volunteering when there were thoughts of disbanding it altogether.

– He was a senior critic at Art News (1956-62), a critic at the New York Post (1960-64), and is currently a contributing editor at Art in America.

– He held a New Years party in 1964 for 200 people. It was “a blast” and, as Sandler later wrote, “turned out to be the major social event of my art world” as the end of Abstract Expressionism’s reign was nigh.

– Sandler co-founded Artists Space with Trudie Grace in 1972, and ever since the indespensable SoHo nonprofit has maintained an artist registry called the Irving Sandler Artists File that has since been transferred online, garnering over 10,000 users.

– He has been on faculty at SUNY Purchase since 1972 and is currently professor emeritus. Throughout his tenure at SUNY, he lobbied to remain in the Visual Arts department (with the artists) rather than be transferred to the Humanities’ Art History Department as the university wanted.

– He once served as the director of the Neuberger Museum of Art.

MAJOR WORKS

– The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (1970)

– The New York School: The Painters and Sculptors of the 1950s (1978)

– American Art of the 1960s (1988)

– Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s (1997)

– A Sweeper-Up After Artists: A Memoir by Irving Sandler (2004)

– From Avant-Garde to Pluralism: An On-the-Spot History (2006)

RELATED LINKS

Know Your Critics: What Did Harold Rosenberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Clement Greenberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Meyer Schapiro Do?