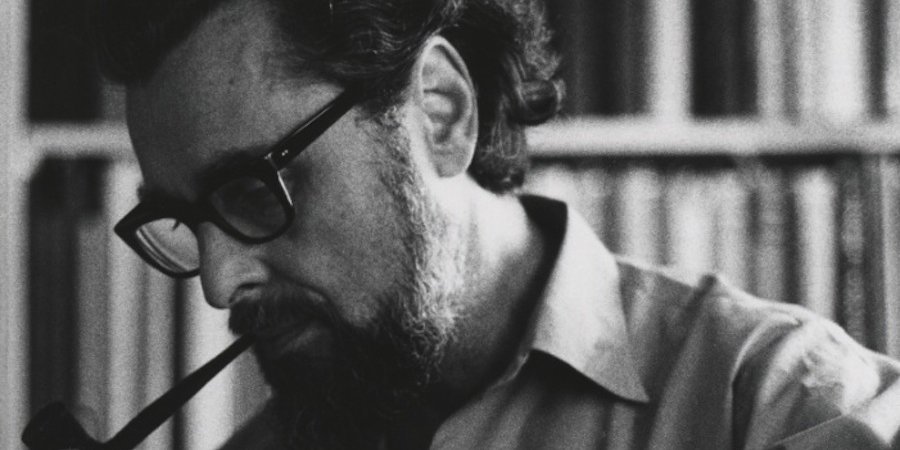

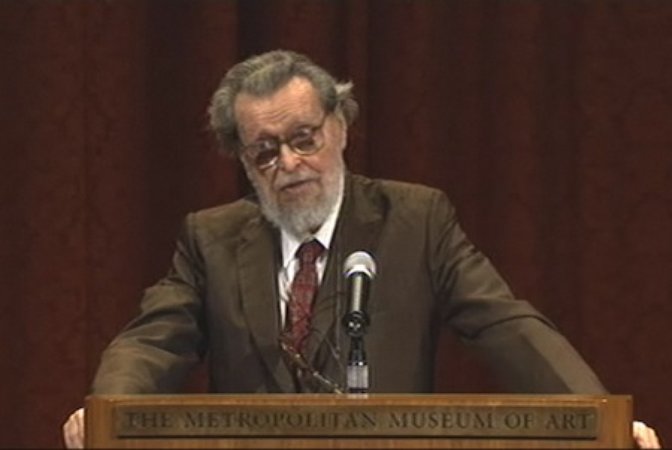

If you could have dinner with just one 20th-century art historian, you might want to choose Leo Steinberg (1920-2011). Known for delivering garrulously wide-ranging lectures and papers that were as lucid as they were revolutionary, he was also admired for his wit, dropping in enough jazzy lines that Woody Allen could have cherry-picked them for material.

The following is a glimpse into his dazzling mind.

WHAT DID HE DO?

Born in Moscow, Steinberg was raised in Berlin until his family fled the Nazis in the mid-'30s and moved to England. In London, he attended the Slade School of Fine Art, then came to New York as soon as the war allowed it, in 1945. He enrolled at New York University’s Institute of Fine Art in the 1950s and received his doctorate in 1960, writing his dissertation on the brilliantly idiosyncratic Baroque architect Francesco Borromini, archrival of Bernini.

While still in his student days NYU, Steinberg began moonlighting as an art critic with an eye on the city's emerging postwar milieu. He called it his “secret life” because “few art historians took the contemporary scene seriously enough to give it the time of day. To divert one’s attention from Papal Rome to Tenth Street, New York, would have struck them as frivolous—I respect their probity.”

After realizing that his fellow critic and intellectual Thomas B. Hess (then editor of Art News) was right when he said "it takes years to look at a picture," Steinberg moved away from criticism to write more in-depth art-historical essays and analysis. But while he specialized in Renaissance and Baroque art, he maintained a keen interest in and involvement with contemporary art, according it the same sedulous attention that he gave the Old Masters. This combination of gravitas and up-to-date engagement gave Steinberg a privileged position in the dialogue around the newest art, and he emerged as not only a witness but an important instigator in the transition from Abstract Expressionism (and Greenberg-ian strictures) to the next generation of artists, who were leaving behind painterly theatrics for the icier criticality of Pop.

In 1960, Steinberg told an audience at Washington University in St. Louis that “Abstract Expressionism was history and that the next wave had come in with Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns," he recalled in Encounters With Rauschenberg (2000). "It was the last time that I offered anything approaching a market tip, but the sponsors, and then the press, thought I was cuckoo.” He went on to explain: “What was needed in the mid-sixties was resistance to Clement Greenberg, and I figured that to do it effectively, to champion Rauschenberg required a special strategy. Mine was to campaign on Greenberg’s own turf, on enemy territory, as it were—not in defense of Rauschenberg’s subject matter, or kooky procedures, or puckish invention—but on formalist grounds and precisely in terms of the picture plane.”

On top of his opposition to Greenberg’s pictorial strictures, Steinberg disagreed with the critic’s dialectal separation between the “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” as Greenberg titled his 1939 essay that used "kitsch" as a synonym for popular culture. Steinberg's response to that landmark text was the 1962 Harper's essay “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public,” in which he made a startlingly democratic appeal: “May we then drop this useless, mythical distinction between—on the one side—creative, forward-looking individuals whom we call artists, and—on the other side—a sullen, anonymous, uncomprehending mass, whom we call the public?” Steinberg found the boundary between public and the lionized artist to be fluid, since the avant-garde can be curmudgeonly and conservative too, in its own way. “Whenever there appears an art that is truly new and original, the men who denounce it first and loudest are artists,” he slyly noted.

Steinberg also questioned—most notably in his 1967 essay, “Objectivity and the Shrinking Self”—the art-historical pursuit of objectivity, portraying it as both an unattainable ideal and a limited means of understanding an artwork or concept anyway. Instead, he found value in disclosing the process of intellectual discovery, and in detailing the messy subjectivities woven into that process. That said, Steinberg did not condone an author's projecting onto an artwork; rather, he asked that art history divulge the roads it took to get to its conclusions and reevaluate the routes previously taken. In other words, he argued for transparency.

In his own writing, consequently, Steinberg freely allowed his methods for understanding new, confounding work to play out on the page—to a degree some detractors considered over-sharing. Two of the most confounding new artists who entered his sights, and whom he endeavored to understand from their art-world beginnings, were Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

Considering them both to be transformative figures, Steinberg located a particularly significant moment of transition in contemporary art at large in Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning Drawing from 1953, a seminal piece of conceptual gamesmanship that the artist created by asking Willem de Kooning for an intricate layered work of ink, graphite, crayon, and charcoal and then meticulously erasing it. Steinberg wrote that “his erasure opened the portals of art to all wannabe artists with no talent for drawing. This open-door situation would have arrived anyway, what with digitized animation, video, installation, etc. But Rauschenberg anticipated and legitimized the process from within art…. I suddenly understood that the fruit of an artist’s work need not be an object. It could be an action, something once done, but so unforgettably done, that it’s never done with—a satellite orbiting your consciousness, like the perfect crime or a beau geste.”

The work of Jasper Johns, for its part, looked to Steinberg like a destabilizing turning of the page on Abstract Expressionism. After seeing Johns’s Target With Four Faces (1955), a piece that merges painting with sculpture and what could be termed graphic design (in the case of the target, an emblem "the mind already knows"), the scholar wrote that “the picture remained with me—working on me and depressing me.” He couldn’t figure out why, but then eventually realized that “what really depressed me was what I felt these works were able to do to all other art. The pictures of de Kooning and Kline, it seemed to me, were suddenly tossed into one pot with Rembrandt and Giotto.” As for those who said Johns was sidestepping subject matter by using banal objects, Steinberg joked that if that was the artist's intention, “he had surely failed—like a debutante who expects to remain inconspicuous by wearing blue jeans to a ball.”

While monitoring the revolutions in contemporary art, and analyzing the legacies of trailblazing figures like Picasso and Rodin, Steinberg at the same time continued his work on the centuries-old achievements of his beloved Italy. The Renaissance was not immune to his irreverent treatment. When he published The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, his 1983 classic on cultural and aesthetic repression, the New York Times summed up that “the book grew out of a question that had apparently occurred to no other modern scholar: Why is it that in so many Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and Child, the infant Jesus’s genitals are actively displayed to viewers both within and without the picture?”

What manner of art historian was engaged enough with current art to help shift the tides away from Greenberg’s formalism but who could also manage to cast fresh light on the most pervasive imagery of the Renaissance? One worth reading. Steinberg’s work continues to remind us to ask new questions, interrogate the answers, and allow ample humor to pepper the process.

BONUS FACTS

– Steinberg was born Zalman Lev Steinberg.

– His father, Isaac, was Lenin’s commissioner of justice before the family fled to Berlin.

– At the age of 12 he picked up his first art book: Richard Hamann’s The Early Renaissance of Italian Painting. It was too expensive for his parents to buy for him, Steinberg recalled in his 2002 acceptance speech for the College Art Association’s Distinguished Scholar Award, but “the bookseller turned to my father and said, ‘Look, any day now Hitler will be coming to power [as indeed Hitler did five weeks later, January 30, 1933], and the first thing the Nazis will do is close this shop. So why don't you just take the book for your boy.’ I have the book still, inscribed in pencil in a 12-year-old's hand, ‘1932, for Chanukah.’”

– He wrote for Commentary, The Partisan Review, Art News, Artforum, and October, among publications.

– He spent most of his teaching career at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was the Benjamin Franklin Professor of the History of Art from 1975 onwards. He also taught at Hunter College and CUNY (1961-75), Columbia, Harvard, and the University of Texas, Austin.

– In 1971 he developed the curriculum for the then-new Graduate Center at CUNY along with art historian Milton Brown.

– He donated his collection of over 3,200 prints to the Blanton Museum at the University of Texas, Austin, where he had been a distinguished visiting lecturer in the 1990s. He also began collecting Old Master prints in the 1960s, adding other eras over the decades.

– He concluded his talk “False Starts, Loose Ends” at the 2002 College Art Association conference in Philadelphia with some erudite self-deprecation: “You may be amused to learn that more writing is planned, for which I already have some adequate titles, such as 'Flotsam & Then Some.' My favorite is a stage direction taken from an obscure Elizabethan play: 'Exit Clown, Speaking Anything.'”

– Damien Hirst appropriated the name for his chain of editions emporiums from Steinberg's 1972 book Other Criteria: Confrontations With Twentieth-Century Art.

MAJOR WORKS

– “Contemporary Art and the Plight of Its Public” (lecture at MoMA, 1960; Harper’s Magazine 1962)

– “The Philosophical Brothel” about Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles D’Avignon (Art News, 1971)

– “Reflections on the State of Art Criticism” (Artforum, 1972)

– Encounters With Rauschenberg (A Lavishly Illustrated Lecture) (1998)

– The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (1996)

– Leonard’s Incessant Last Supper (2001)

– Other Criteria: Confrontations With Twentieth-Century Art (1972)

RELATED LINKS

Know Your Critics: What Did Harold Rosenberg Do

Know Your Critics: What Did Clement Greenberg Do

Know Your Critics: What Did Meyer Schapiro Do

Know Your Critics: What Did Irving Sandler Do?