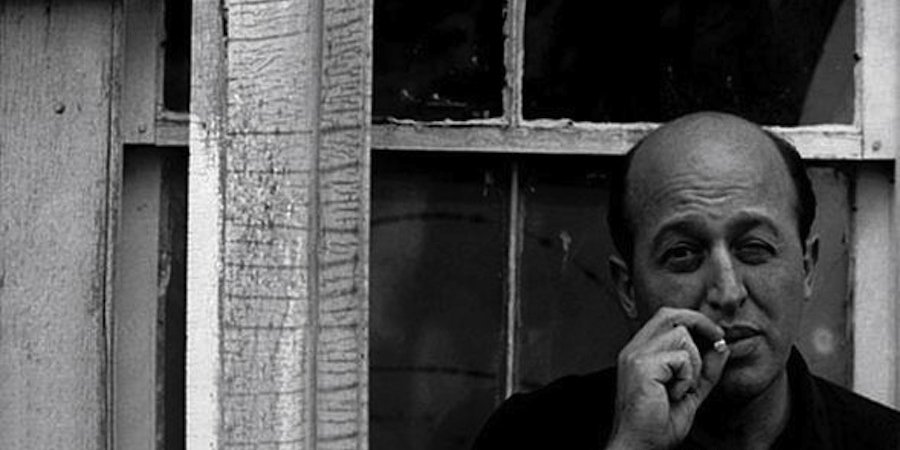

Possibly the most renowned art critic in American history, Clement Greenberg (1904-1994) held sway for years in the postwar period over not only the popular perception of contemporary art being made in this country but also how the artists themselves thought about it and brought it into being in their studios. While his reign eventually came to an end, with opinion turning against his dogmatic edicts, his ideas—which he published in the pages of the Partisan Review, the Nation, and Commentary—remain a critical touchstone for anyone trying to grasp the Abstract Expressionists, the Washington Color School painters, and others who were engaged in formalist, "non-objective" art, as abstraction was called back then. What follows is a précis on Greenberg's key accomplishments.

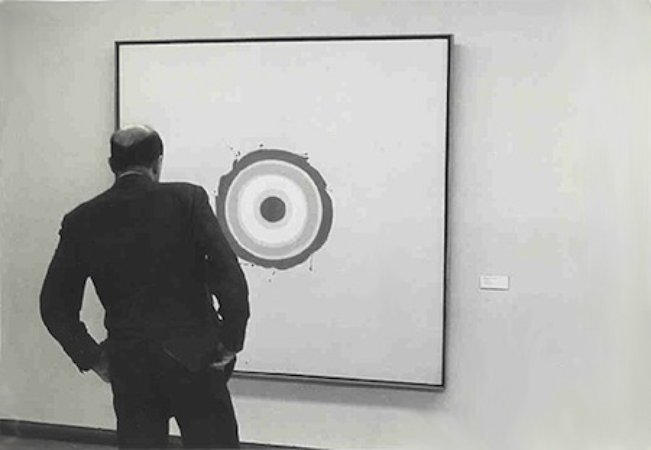

WHAT DID HE DO? Greenberg admiring an especially flat painting by Kenneth Noland

Greenberg admiring an especially flat painting by Kenneth Noland

As a prolific critic, Clement Greenberg developed his theories on the page—as he put it, “I would not deny being one of those critics who educate themselves in public.” Greenberg’s intensely influential focus was on the notion of “formal purity.” Through his praise of Hans Hofmann in the Nation in 1945, Greenberg described his own critical priorities: “I find the same quality in Hofmann’s painting that I find in his words—both are completely relevant. His painting is all painting; none of it is publicity, mode or literature. It deals with the crucial problems of contemporary painting on its highest level in the most radical and uncompromising way, asserting that painting exists first of all in its medium and must there resolve itself before going on to do anything else.”

If Greenberg’s mode of coming up with his theories was an improvisitory work in progress, his bets on artists were at times visionary. His first mention of Jackson Pollock—almost the first mention of the artist in print—was in a 1943 review for The Nation: “There is both surprise and fulfillment in Jackson Pollock’s not so abstract abstractions. He is the first painter I know of to have got something positive from the muddiness of color that so profoundly characterizes a great deal of American painting.” While he critiqued Pollock’s larger paintings as the artist taking “orders he can’t fill,” Greenberg did find the smaller work “much more conclusive… among the strongest abstract paintings I have yet seen by an American."

As Pollock developed from his early abstractions to the “drip” paintings for which he is known, his work fell more into Greenberg’s ideal—painting about space and color and, above all, about painting itself. Greenberg argued in his 1948 essay “The Crisis of the Easel Picture” that “the dissolution of the pictorial into sheer texture, into apparently sheer sensation, into an accumulation of repetitions, seems to speak for and answer something profound in contemporary sensibility.”

For Greenberg, the new artistic expression followed Hans Hoffman’s “dissolution of the subject”—and thus moved away from the recent, still subject-bound European movements like Surrealism or even Cubism. Nonetheless, Greenberg maintained that this advancement from subject matter towards the flatness of the picture plane was part of a continuum—an evolution that began with Manet, who he held created the first "Modernist pictures," and saw its flowering in Abstract Expressionism. In fact, he felt that flatness was "more fundamental than anything else to the processes by which pictorial art criticized and defined itself under Modernism," because, he explained, "flatness alone [is] unique and exclusive to pictorial art."

But Greenberg did not want that evolution to reverse. When Pollock started to move away from drip painting, and Willem de Kooning showed his less-than-totally-abstract Women series at the Sidney Janis Gallery, Greenberg was not pleased. He soon moved away to champion a new group of artists who were emerging in the nation's capital, the Washington Color Field painters—a group including Kenneth Noland, Helen Frankenthaler, and Morris Louis who achieved what the critic considered highly admirable flatness by pouring thin paint directly into the weave of their canvases.

As time went on, Greenberg's orthodoxy when it came to his bans on figuration and multidimensional texture in painting became ripe for a backlash among artists seeking non-Greenberg-ian ideals. Enter Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

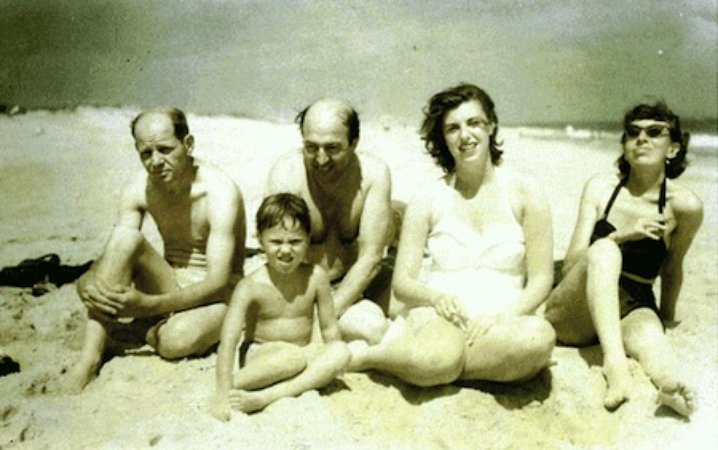

BONUS FACTS A day at the beach with (from left) Jackson Pollock, Greenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, and Lee Krasner

A day at the beach with (from left) Jackson Pollock, Greenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, and Lee Krasner

– Greenberg and Helen Frankenthaler, 24 years his junior, were romantically involved from 1950 to 1955 and remained close until the critic's death.

– He curated on occasion, notably a show called “Talent 1950” with Meyer Schapiro at the Samuel Kootz gallery that featured figures like Franz Kline, Elaine de Kooning, and Larry Rivers alongside the now-forgotten Esteban Vicente, Al Leslie, and Manny Farber.

– Greenberg had enemies. But he also had a decades-long correspondence with his college friend Harold Lazarus. The letters, posthumously anthologized by Greenberg’s widow, pulse with humanity. From “Clem” to Harold: “Yes, the honors pile. But I want gossip, sexual intrigue, back-biting and hair undoing. I want women, confidences, confessions & broken hearts. Dissipation, indiscretions, glitter, dash, sparkle, sin” (September 25, 1940). On art writing: “Everyone dislikes technical criticism of painting; and there’s no other decent kind. What’s wanted is horseshit. And the horseshit is so easy to write brilliantly, but I shan’t” (September 25, 1940).

– In 1966, the English artist John Latham held an event called "Still and Chew" at which he invited attendees to chew pages of Greenberg’s Art and Culture. Fermented and distilled, the masticated book was then returned to the St. Martin’s School of Art library. MoMA acquired the vials in 1969.

– Greenberg also moonlighted as a poet.

MAJOR WORKS

– “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (Partisan Review, 1939)

– “Towards a New Laocoon” (Partisan Review, 1940)

– “Abstract Art” (The Nation, 1944)

– “The Crisis of the Easel Picture” (Partisan Review, 1948)

– “American Type Painting” (Partisan Review, 1955)– “Modernist Painting” (Voice of America lecture, 1961)

– “After Abstract Expressionism” (Art International, 1962)

– Art and Culture: Critical Essays (1961)

RELATED LINKS

Know Your Critics: What Did Harold Rosenberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Meyer Schapiro Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Leo Steinberg Do?

Know Your Critics: What Did Irving Sandler Do?