Reopening this week after being closed a week into its runs due to the pandemic, The Tate Modern will present 'Andy Warhol', an eponymous retrospective tracing the life and career of the peerless pop artist and icon. Popularly radical and radically popular, Warhol was an artist who reimagined what art could be in an age of immense social, political and technological change.

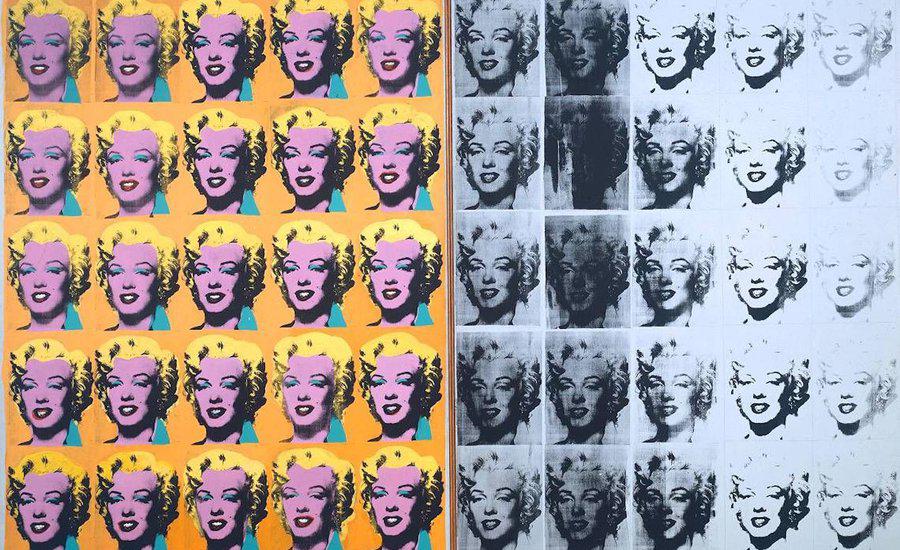

In this Anatomy of An Artwork story - the latest in a series in which we spotlight a single piece of art from a major new exhibition - we’ll do a deep dive on the Warhol masterpiece, 'Marilyn Diptych1962', with help from Tate curator Gregor Muir. When you've read it, check out our Artspace-exclusive gallery of this legendary artist’s work, available now for you to buy.

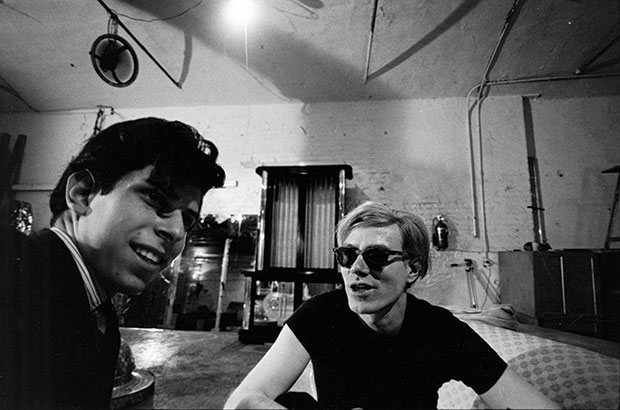

Andy Warhol at the Factory, New York, from Factory: Andy Warhol by Stephen Shore

Andy Warhol at the Factory, New York, from Factory: Andy Warhol by Stephen Shore

In her 1979 book of essays, The White Album, writer Joan Didion noted; “We tell ourselves stories in order to live. We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the 'ideas' with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” Abstraction is the primary coping mechanism of society in flux— that trusted old guard under siege by the charring flames of change. We cling to symbols like cruel lovers or distant parents, hoping to discern the outlines of a compass in otherwise unyielding negatives of truth.

Therein lies the tricky bit about discussing Marilyn Monroe or Andy Warhol with any real authority; it simply can’t be done. Both boast legacies too capacious and diluted for authentic examination, and both manufactured that dilution as an essential part of their shared but distinct mystiques.

Perimeter-glitching details that should humanize these people—Monroe was an abused foster kid from the rural Midwest who transformed herself into a cultural apotheosis of femininity, Warhol was a shy, sick, gay child of immigrants who single-handedly redefined contemporary art— seem only to bolster their dramatic mythological arcs. Warhol’s deployment of Monroe’s image magnified her cultural impact to a point of brazen nothingness, which was the whole point, of course. Warhol still reigns as the crown prince of vacancy, and Marilyn, despite her best efforts, was its queen.

Jean Gossaert - Diptych of Jean Carondelet”, 1517

Jean Gossaert - Diptych of Jean Carondelet”, 1517

Onto the art: the history of diptychs is an explicitly educational one. The term’s etymology derives from the Greek root 'dis', meaning 'two', and 'ptyke', meaning 'fold', originally coined to describe the hinged, collapsible tablets popularized prior to the advent of the printing press. As Christianity gained traction across the Roman Empire, portable altarpieces grew more and more en vogue , helping to increase iconographic accessibility for vast swathes of illiterate citizens.

From 500 to the late 1100s, before the proliferation of Gothic cathedrals, stained glass windows and allegorical paintings on canvas, morality tales still required illustration, and these modest little wood panels, often depicting the Virgin Mary and various other attendants, appeared on countless altars throughout Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Diptychs could also serve as testaments to individual piety, wealth, or social status, too; the pallid face of Dutch cleric Jean Carondelet opposite a luminous Virgin and child (“Diptych of Jean Carondelet”, 1517) made painter Jean Gossaert a household name in the 16th century, and the most famous example in the Western canon, the Wilton Diptych of 1396, features patron King Richard II being presented by three saints to the Mary and the baby Jesus, each delicately limned in gold leaf applique. These objects intertwined instruction with devotion, sprinkling in just enough material spectacle to catch the eye and keep it captive.

The Wilton Diptych of 1396

The Wilton Diptych of 1396

It’s little wonder, then, that a contemporary artist raised in the Catholic, Slavic ghettos of Pittsburgh found fit to apply this theological paradigm to celebrity, America’s most fashionable form of faith. Andy Warhol created the Marilyn Diptych silkscreen just four months after Monroe’s barbiturate overdose in August 1962, an event that inspired a nearly 50% spike in Los Angeles-area suicides for weeks and launched more conspiracy theories, drag acts, pop songs, biopics and active shrines than even the legend herself could shimmy a shoulder at.

Monroe was 36 at the time of her death, long in the tooth for a sex symbol and plagued by a heady combination of depression, malaise, and addiction that made her quite the liability on film sets. The press lambasted her efforts at serious acting, her marriage to Death of a Salesman playwright Arthur Miller had snapped under the pressure of his fetishistic cruelty, and years of crash diet-induced gallstones and untreated endometriosis led her in and out of the hospital on a bimonthly basis. Productions halted, lawsuits mounted, and things got hard—too hard.

Monroe’s passing effectively froze her in time, preserving the doe-eyed, girlish vulnerability and nubile form simultaneously revered and reviled by her adoring public. Her personhood had ceased en entire somewhere in the early ‘50s, when the “dumb blonde” archetype she minted onscreen subsumed the genuine, flesh-stricken strife she couldn’t quite outrun. Eaten alive by emblematic expectation, Monroe still couldn’t achieve even a wavering semblance of humanity.

In Ways of Seeing, art theorist John Berger declares, “ Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object—and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.” Monroe was trapped in a revolving room of one-way mirrors. She never got out.

Marilyn Monroe screengrab from Niagara, 1953

Marilyn Monroe screengrab from Niagara, 1953

If ‘62 was the worst year on record for Monroe, it was gang-busters for Warhol, who had successfully transitioned from a lucrative career as a commercial illustrator (photographer John Copland insisted that “no one drew shoes the way Andy did… [with] a sort of sly, Toulouse-Lautrec sophistication”) into the controversial fine artist du jour . A July 1962 show with Ferus Gallery in California introduced exasperated critics to his soupcans, a splash big enough to result in a solo turn at New York City’s Stable Gallery in November. Marilyn Diptych debuted there, a potent, droning silkscreen painting that sports 50 gridded iterations of a Monroe press headshot from Niagara, the 1953 flick best remembered for that skin-tight, acid pink dress.

“In August 62 I started doing silkscreens," Warhol said, commenting on the painting. "I wanted something stronger that gave more of an assembly line effect. With silkscreening you pick a photograph, blow it up, transfer it in glue onto silk, and then roll ink across it so the ink goes through the silk but not through the glue. That way you get the same image, slightly different each time. It was all so simple quick and chancy. I was thrilled with it. When Marilyn Monroe happened to die that month, I got the idea to make screens of her beautiful face, the first Marilyns.”

The format of the Marilyn Diptych, 1962, mirrors the form of a Christian work of art depicting the Virgin Mary on one side and the crucified Jesus on the other. The comparison references the idolization of Marilyn Monroe. Gregor Muir, Director of Collection, International Art, at Tate and curator of the New Andy Warhol show told Artspace:

"This Diptych was put together not by Warhol, but by the collector (art and design show organizer Emily Hall Tremaine). She bought one painting and then found another and said, 'Can I put these two together Andy?' He said ‘gee whizz that looks great.’ And that is how the painting came to be. "There’s an amazing process to it. On the right, on the silver side, what you’re seeing is the underprinting which Warhol did in many of these works. What he was doing was laying down an early sort of drawing that he could then paint over.

Andy Warhol - Marilyn Diptych, 1962

Andy Warhol - Marilyn Diptych, 1962

"What you see on the left is the paint over that underprinting, and then another print on top. There is some interesting game playing going on. You see on the left, that every single face is different. Every one is handpainted, loosely according to the underprint. But it’s interesting to see the difference. You’ve got a clean face throughout on this [the left side], and on the right you see the decaying echo of Marilyn, a painting committed by Warhol not long after her death.

"One of the key things for this Tate exhibition is religion and death, coupled with the idea of clear identity and also this idea of the immigrant story, and the upbringing that Warhol had. While there are many questions about the fact that Warhol was a man of faith, sometimes unknown, his take on faith is an important question. It’s very interesting to see how Warhol could ever have escaped religion given the upbringing that he had. His mother knew the liturgy by heart, and he went to church every day in Pittsburgh, often walking miles. The area was referred to by Warhol as the Czech ghetto. It’s clear he lived in a deeply European bubble. Warhol is, in a sense, looking at religious iconography, it's surrounding him and he's fully aware of the power of the Greek Byzantine church. Here is Marilyn, as a religious icon herself."

The left panel is also a full-throttle study in color theory; Warhol’s fluky, sterile touch renders the starlet’s face in lavender and hair in pyretic yellow against a searing orange background. The right panel, a starker documentation of the piece’s procedural underpinnings, repeats the pattern in black and white, a smudged, stained lyric that evokes the very newspapers precipitating Monroe’s fatal denigration. The contrast is as graphic as it is haunting, insistent the way a nervous cackle in an empty room might feel.

If Lyotard simplified the postmodern as “incredulity towards metanarratives”, Warhol electrified the concept in a visual language both punishing and laudatory, using the syntax of capitalist exploitation to steep viewers in their own empathetic shortcomings. His interventions evoke a casual timbre of violence, the imprint of a necessarily hollow obsession. This is a hot, mean vacancy, the sort that troubles and entrances in equal measure. 60 years later, its dynamism is just as immediate, and its story is just as hypnotic.

Take a look at the many Warhol works for sale on Artspace now on our Andy Warhol artist page , Buy Phaidon's Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonne Volumes 1-5 , made in collaboration with The Andy Warhol Foundation; Giant Size , the best selling visual biography featuring over 2,000 photographs and images and Stephen Shore's photographic document Andy Warhol: Factory spanning the years 1965-67.

Andy Warhol at Tate Modern has been extended to run until November 15, 2020. Details of the show here.