While "free speech" is most publically illustrated by debates over whether or not Nazis should speak at universities, these culture wars are playing out across the art world as well. The most recent lawsuit against Jeff Koons––in which he was, yet again, found guilty of plagiarism––has renewed debates about copyright infringement, as has the E.U.’s proposed Copyright Directive, which would ban people from sharing copyrighted images online. A recently rescinded D.C. amendment, which would have banned “vulgar” and “overtly political” artwork, renewed fears about censorship, as did a German Far Right rally widely protested by cultural workers. Open Casket, Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, and the letter signed by many black artists for the painting to be removed from the 2017 Whitney Biennial, crystalized ongoing conflict over cultural appropriation.

In the list below, we use these three topics––appropriation, censorship, and copyright––to break down the art world’s “free speech” debates.

Copyright

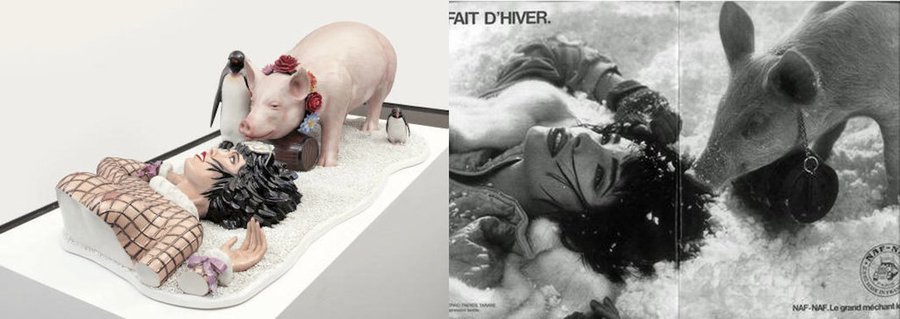

Copyright states that the creators of original works have the exclusive rights to their use and distribution. Copyrights usually only last for a limited time. Jeff Koons, whose art is based, in large part, on appropriating and re-evaluating advertising and mass culture, has unsurprisingly run into copyright issues many times. Koons was most recently sued for plagiarizing Fait d’Hiver by Franck Davidovici; Davidovici made the image in 1985 as an ad for French clothing brand Naf Naf. Koons made the image into a sculpture in 1988. Koons was found guilty, and was ordered to pay $153,000 in damages, although the sculpture itself was not seized.

Jeff Koons, Fait d’Hiver, 1988. Photo: Christie’s. Franck Davidovici, Naf Naf ad, 1985. Photo: Naf Naf.

Jeff Koons, Fait d’Hiver, 1988. Photo: Christie’s. Franck Davidovici, Naf Naf ad, 1985. Photo: Naf Naf.

Copyright has, like everything else, been complicated by the internet. In an attempt to update copyright law to the digital age, a recently proposed E.U. Copyright Directive would prevent copyrighted images from being shared online using filter checks, which would check the image against a database of archived materials before allowing it to go up. On the one hand, the directive would hold social media platforms responsible anytime an artist’s copyrighted work was uploaded without their permission. On the other hand, the measure might crack down on memes, which often work by altering copyrighted imagery, as well aritsts who appropriate and repurpose images that are copyrighted but online.

Censorship

According to the ACLU, censorship is “the suppression of words, images, or ideas that are ‘offensive,”; it happens “whenever some people succeed in imposing their personal political or moral values on others. Censorship can be carried out by the government as well as private pressure groups.” As the ACLU also points out, “Free expression may be restricted only if it will clearly cause direct and imminent harm to an important societal interest. Even then, the speech may be silenced or punished only if there is no other way to avert the harm.” The question of who is at risk of “imminent harm” has, of course, always been subject to structural biases.

We can see how bias plays out in, for instance, an amendment proposed by the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities (DCCAH), which would have allowed it to terminate funding for any grant recipient whose work was considered “lewd, lascivious, vulgar, overtly political, or excessively violent, constitutes sexual harassment, or is, in any other way, illegal.” Deepak Gupta, a constitutional lawyer working with the ACLU, argued that the amendment was dangerous because of its vagueness, allowing it to be applied indiscriminately based on the DCCAH’s own standards of e.g. lewdness, even if no one was at risk of “imminent harm.”

Never Again by Monica Bonvinici, image via her website

Never Again by Monica Bonvinici, image via her website

In Germany, censorship arguments were ignited when nearly 8,700 German cultural workers protested against the country’s interior minister, Horst Seehofer, asking him to step down. Artist signees included Ulf Aminde, Monica Bonvicini, and Parastou Forouhar. Seehofer, arguably exercising his “free speech,” had argued that immigrants were “the mother of all problems” in September. When a racist Far-Right mob––which was protected by free speech, despite the mob’s repeated calls to violence––broke out in the German town of Chemnitz, Seehofer stated that he would have joined the rally: “I also would have been going into the streets.” Seehofer has not resigned.

Cultural Appropriation

Cultural appropriation occurs when people from a majority culture adopt elements of a minority culture. Unlike cultural exchange, in which both sides are on equal footing, cultural appropriation is the result of a power imbalance created by systemic oppression, in which the majority culture can extract value from the minority culture however they want. Sometimes, cultural appropriation takes the form of objects (i.e. a white woman wearing a sari). Sometimes, it is about using other people’s history and emotions, i.e. a non-Native person writing a novel from a Native American person’s point of view.

Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, shown at last year’s Whitney Biennial, exemplified both kinds of cultural appropriation. Schutz’s painting was a portrait of Emmett Till, a black fourteen-year-old boy who was lynched by two white men in Mississippi in 1955. In an open letter to the curators and staff of the Whitney Biennial signed by many other black artists, artist and writer Hannah Black asked for the painting to be taken down and destroyed. “As you know, this painting depicts the dead body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the open casket that his mother chose, saying, ‘Let the people see what I’ve seen.’ That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways.”

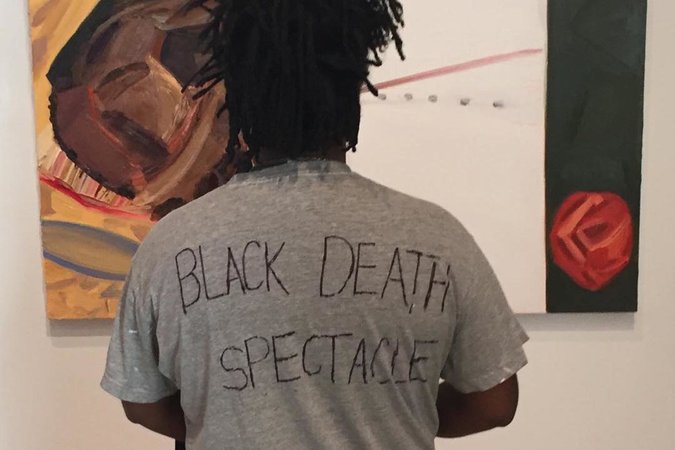

Artist Parker Bright's protest against Dana Schutz's Open Casket, image via W Magazine

Artist Parker Bright's protest against Dana Schutz's Open Casket, image via W Magazine

While Schutz’s advocates defending the painting on the grounds that it would inspire empathy for black suffering, the letter’s point is that more information does not always make people more empathetic. Instead of reversing white supremacist power dynamics via empathy, the painting, Black argued, solidified those dynamics by proving that white people could access black suffering, and use it as “raw material,” whenever they wanted, even when that went against black people’s wishes. Artist Parker Bright protested this mode of extraction by standing in front of the painting wearing a shirt that read "Black Death Spectacle." Black’s detractors, however, accused her of censorship. If something was censored on the right, they argued, then it could just as easily be censored on the left, and that this was a step towards fascism. The painting was not taken down.

RELATED ARTICLES:

The Eternal Puppy: the Philosophy of Jeff Koons in 20 Revealing Homilies

How Well Do You Know Jeff Koons? Take This Quiz

Mysticism, Memes, and Bratty George Washington: 2018's Best Pieces of Art Criticism