The art world has problems, and you've probably already heard about them. Countless reports over the last few years about mid-tier galleries closing their doors illustrate the unsustainability of the current gallery model, which relied on stable rents and overhead, along with a steady stream of income from a shrinking upper-middle class. A few weeks ago, Artspace reported on art fair organizers’ attempts to revive their models with marginal attempts to lure struggling mid-tier galleries back into the rat race; we questioned whether the art fair model is worth saving in the first place. And last month Artie Vierkant wrote for ARTnews about the systemic lack of health benefits for art industry workers, regardless of their role, or the wealth of the company they work for. The conversations surrounding the at-risk health of the art world have been focused primarily on the art industry itself—galleries and dealers, auction houses and art fairs. But what about artists? Artists have always been at the bottom of the totem pole economically—this is nothing new. But that doesn’t mean that it has to be that way, forever.

If the art world needs fixing, and if we’re taking the time to figure out how to fix it, why not look for models that actually help individual artists, not just the businesses that profit off of them? Why not turn our fear and frustration into a productive dialogue that simultaneously shifts the locus of concern and prioritizes the financial viability of being an artist? In this three part series on Artpsace, I hope to do just this. Examining the financial models of other creative industries, like film and music, I look for lessons we can apply to the art world—some that are already beginning to emerge in practice, and others that are speculative.

The purpose of this exercise isn’t to provide be-all-end-all solutions; I don’t claim to have the answers. Instead, the purpose is to, at the very least, illustrate that the current system is not natural, it’s just been normalized. It could have been different, and it can be different. And it is different, in other industries. By using existing models from the industries of art and film we can begin to at least suggest that there are possible alternatives to the art world we know and love to hate.

Part one of this series looks at how musicians and recording artists make money in the music industry; at how an industry’s economics formulate the relationship between artist and audience versus artist and patron; and at how subscription-based models could provide artists with more financial autonomy, and provide fans with more stake. (In part two, I’ll speculate on how corporate sponsored artists might operate using, again, the music industry as a case study; and in part three, I’ll look at both the history and possible futures of art-world collectivizing in the interests of healthcare among other benefits, drawing from examples in the film industry’s commonplace guilds and unions.)

What Can the Art World Learn From the Subscription-Based Model of the Music Industry?

In the music industry, recording artists (can) make money when their music is listened to, but not necessarily owned. While some listeners buy music directly from recording artists (or their record labels), the grand majority don’t—especially as younger consumers are replacing generations who grew up listening to records, tapes, or CDs. Platforms like Youtube, Soundcloud, and Spotify offer free streaming services, as well as paid subscriptions. These platforms give content producers a fee for every time (or certain number of times) a song or video is played, above a certain threshold. (In the case of more established recording artists, this fee goes to the record label that the artist has a contract with, and that record label pays the artist as defined by the contract. In the case of artists who remain independent and unsigned, the fee goes directly to the artist.)

Where does this money come from? Youtube, Soundcloud, and Spotify generate income from advertisers who stream ads in between songs, and from listeners who chose to pay for a subscription in return for ad-free listening. The more a track is played by fans, the more valuable it becomes to advertisers, and the more money the artist makes. So in today’s music industry, where the majority of content is accessed through subscription-based streaming platforms, musicians are rewarded by being popular. The size of their fan base determines how much money they make.

Visual artists, on the other hand, typically make money not when their work is seen and experienced by a large audience, but instead, when their work is withdrawn from its audience. Though a piece may be accessible to the artist’s fans when on view in a gallery, the artist only generates income when that piece has been sold, removed from the public viewing space to become someone’s property. While some collectors may loan out works, or occasionally open up their collections for public viewing, the grand majority of artworks bought by private collectors (and the grand majority of artworks are bought by private collectors) are never seen in public again. Unlike songs, an artwork’s value doesn’t increase when its consumption is shared by many. It’s value is determined by the demand of a few. And it’s profitability requires its separation from its audience.

So, how might we imagine an art world where artists benefit not from scarcity, but from appreciation? Can artist’s audience and fan base is also her consumer and patron? …Where art can be experienced, enjoyed, even owned, by many people, people who aren’t extremely rich, and where, in return, the artist enjoys compensation for providing that experience/pleasure? What can the art world learn from the recording artist’s relationship to platforms like Youtube, Spotify, and Soundcloud?

Before getting into the possibility (and emerging reality) of subscription-based platforms for art, it’s important to note that on some level, the “democratization” of art ownership has been marginally attempted already with the publishing of editions and multiples. And that the reason why original art has value in the first place, is because it is scarce. Unlike a song, which is infinitely reproducible as a digital file, a specific painting on canvas can only be singular. However, when an artwork is multiplied, it becomes less scarce, and thus more affordable and accessible to not only a larger number of people, but also to a different economic class of people (i.e. people who are less rich than the very rich.) So when, for instance, Artspace produces an edition of 100 identical prints by Mickalene Thomas, ownership can be shared by many more, and the artist can make money on multiple sales even though she only had to labor over producing one original master work.

But for now let’s set aside editions and multiples, mainly because they typically apply only to artists who are already blue-chip: well established and selling their original artworks for a significant amount of money. (In the current system, rife with staunch austerity and etiquette, emerging and even mid-career artists are less likely to be approached to produce editions, and less likely to find success in selling them. It’s even almost considered taboo for an artist to produce an edition “before they’re ready”—before their original works are so unaccessible, and demand for their work is so high, that it’s “justified.” Whether or not this should be the case is a judgement best made elsewhere.)

So, back to platforms. If lovers of music can take part in the experience of their favorite music, and in turn give their favorite musicians the opportunity to make money each time they stream, could art lovers participate in the careers of their favorite artists in the same way?

This is already happening, though barely.

Just yesterday, XOXO, “an experimental festival for independent artists and creators who work on the internet” announced they’d be partnering with crowdfunding platform Kickstarter to “build a new platform to help artists share their work, build community, and get paid.” The initiative will launch in about a year, and will essentially be a revamp of Drip, a subscription-based platform that Kickstarter launched last year. Unlike Kickstarter, which connects producers with patrons who donate money once towards a single project, creators with Drip accounts ask their subscribers to pay a fixed recurring fee in exchange for ongoing “rewards.” How much these fees are, how often they recur, and what’s offered in exchange, is set by the artist.

Joshua Citarella, an artist represented by Higher Pictures in New York, offers three different subscription tiers on his Drip account, each billed monthly. For $5 per month, 25 current subscribers receive a digital copy of a book Citarella produced, plus “behind the scenes content”; for $15 per month, five current subscribers receive a physical copy of the book; for $100 per month, three current subscribers (this tier caps at three subscribers) receive a unique 20-inch-by-16-inch artwork at the year’s end. The artist writes on his Drip page, “By signing up you are helping to produce new work, funding research, and production. You’ll see new images of the work being built, get access to live streams and behind the scenes content.” Drip allows their creators to send digital content directly to their subscribers, whether text, photos, audio files, etc.

What Citarella’s Drip account makes clear is that the value of an artist is not reducible to the objects they create. Being a commercial artist means producing commodified art objects, but it also means researching, writing, experimenting, documenting, working. By commodifying these processes, which happen with or without an audience to witness (or pay for) them, Citarella is able to generate a supplemental revenue stream from labor he previously did for free. Why do his contributors pay for it? Some may see it as a fairly priced service; interesting artists generally do interesting things—so a “behind the scenes” peek is certainly valuable to those intersted in the work. Others may see it as something akin to charity; many people donate $5 a month or more to efforts they feel deserve support. Regardless, Citarella generates money by giving his actual audience (fellow artists, followers) a way to support him. The more fans he has, the more money he’s liable to make.

So what would a larger-scale shift towards a subscription-based patronage model look like? Which artists would be rewarded and what kind of art would be left out? Popular artists with big followings will benefit. Artists who are able to lure subscribers with frequent digital content will benefit. Artists who already make digital art content able to be streamed or multiplied—like video—as part of their practice will benefit.

Video art is notorious for being virtually unwatchable. Not because people don't want to watch it, but because it typically requires seeing it in a gallery—which means it's only available during very short periods of time, in very specific cities, and in usually uncomfortable settings where it's almost impossible to catch the beginning of the loop without first watching the end. Unlike googling an image of a painting, which gives a close aproximation of the piece, googling a video piece usually returns stills. Artists and galleries don't want to post full videos online, because if they're accessible to anyone anytime, why would anyone buy it? So, might video artists stand to benefit the most from subscription-based platforms?

Last week I interviewed Lauren Boyle, a member of the art collective DIS. Originally founded as an online magazine in 2010, DIS has since pivoted to produce strictly video content, which Boyle feels is the best medium to use if the goal is to creach the largest audience possible. "We wanted to bubble up the conversations we thought were really important but in a medium we thought people could really easily engage with," she says. DIS has created it’s own subscription-based platform, DIS.art, which makes the artist’s didactic videos (which they call “edutainment”) free to watch for 30 days, after which point the videos are archived behind a paywall. A monthly fee gives subscribers access to archived video content, along with a slew of other ancillary resources that provide context for each video, like reading guides, educational syllabi, etc. "We’re able to create a platform, a library of thought, that people can constantly revisit and be part of."

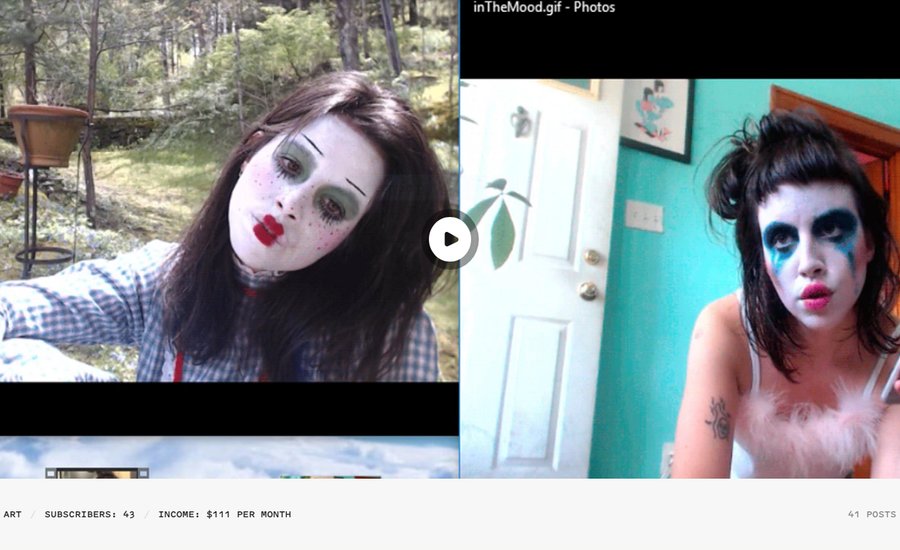

So, it’s becoming more clear that subscription-based platforms are well suited for video and digital media. But what about artworks that exist as single objects, as most artworks do? Good old fashion lotteries, is one way. Like the kind you did at bingo night in your elemetary school cafeteria, though this time the prize isn’t a crazy straw or malted milk balls, it’s an original work of art. Brad Troemel, an artist represented by Marinaro gallery in New York, has been utilizing this model for some time—since before Drip or DIS.art existed. Using Patreon, a platform used for everything from comedy podcasts about theme parks to guides for self help, Troemel offers his subscribers access to daily digital content, which he disseminates via a private Instagram account reserved specifically for his subscribers. He posts mostly memes, the best of which function as explainers for the injustices of the art industry, and also video stories that feature the artist satirically “reporting” at art fairs and other art world events.

But Troemel also makes physical objects, pieces that he’s exhibited in galleries. Every month, Troemel uses a lottery to randomly select one of his subscribers to “win” an original artwork. While having access to Troemel’s entertaining and subversive digital content is likely a draw for many of subscribers, having the chance to own an original artwork by the artist by paying just $5 per month (Troemel’s lowest subscription tier) is reason enough to subscribe. Ultimately, the more people who subscribe to Troemel’s patreon (and the more monthly income he makes), the more “valuable” each monthly artwork give-away becomes. So unlike in the traditional market, where a scarce artwork is only profitable once it becomes removed from its audience, Troemel’s work becomes more valuable the more it’s revealed to its audience.

So, could subscription-based patronage be a new model for the art world? Maybe, but maybe not. As of this past Thursday, Drip is no longer accepting new creators. For all intents and purposes, they'll be going into sleep mode until XOXO takes over next year. But who knows, maybe the revamp will make an impact. And maybe there will already be an uptick in Patreon-using artists by then. Either way, it's already a model that's helping some artists, albiet few, diversify their income streams. It seems worth the experiment. I myself, a visual artist and an educator, am starting one with my collaborator: An ongoing class-as-artwork on Patreon that offers designed reading guides and powerpoints that teach subscribers about the connections we can make between topics like posthumanism, feminism, cyborgs/monsters/chimeras/avatars, biotech and genetics, historical figurative art, and more—and how it all relates back to the work we're making in the studio. Why not? It can't hurt.

In the next installment, we'll look at another way an artist's popularity can increase their ability to make money: corporate sponsorship.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Abolish the Art Fair? Why Basel's New Tiered Pricing Structure Can't Fix a Bankrupt Model

Impressionist And Modern Art Is Losing Value At Auction—Could This Be A Good Thing?

How I Would Change The Art Market: Two Dozen Expert Suggestions For A Saner Industry