An exhibition that takes political action or institutional critique as its subject matter can have a hard time getting its message to move beyond the museum’s walls. Sometimes, though, the word gets out, as seen in these three exhibitions that denounced the status quo and garnered extreme reactions from the higher-ups. The actions taken against these three exhibitions run the gamut—from trustees demanding that works should be removed immediately, to government agents literally running over paintings with bulldozers.

In these excerpts from Phaidon ’s Biennials and Beyond—Exhibitions That Made Art History: 1962-2002 , Bruce Altshuler details three exhibitions that took political action as their motivation and modus operandi. The artists and curators involved did not let vows of censorship or punishment stop them from expressing themselves and, in turn, challenging the powers that be.

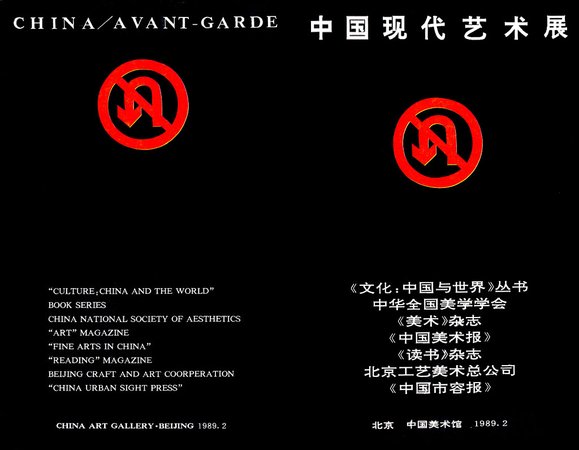

"CHINA /AVANT-GARDE"

National Art Gallery, Beijing, 1989

Cover of the catalog for

China/Avant Garde

, 1989

Cover of the catalog for

China/Avant Garde

, 1989

A few months before the suppression of the pro-democracy movement at Tiananmen Square, “China/Avant-Garde” capped a decade of contemporary art activity in the People’s Republic of China. The exhibition is often remembered as one of subversive content censored by the government, having been closed by the authorities on opening day after an artist shot her own work. But it was mounted with official permission in the most prestigious art venue in China, was reopened after three days and went on to hold all scheduled events. Active repression came later. In the mid-1980s, information about international contemporary art flooded into China, and new art journals proliferated under a more liberal cultural policy. About eighty artist groups formed throughout the country organizing exhibitions and symposia in connection with what became known as the “’85 Art New Wave.” The idea for a national exhibition to survey the new art arose at a 1986 conference in Guangdong province, and approval was obtained for a July 1987 show in the Beijing Agricultural Exhibition Hall. A government campaign against “bourgeois liberalization” prompted its cancelation, but a plan soon developed for an exhibition at the National Art Gallery of China.

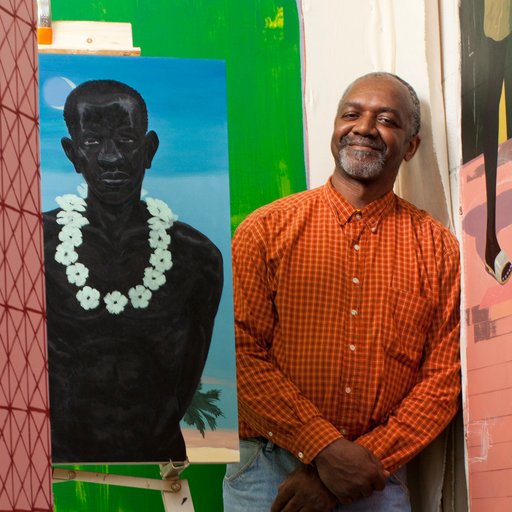

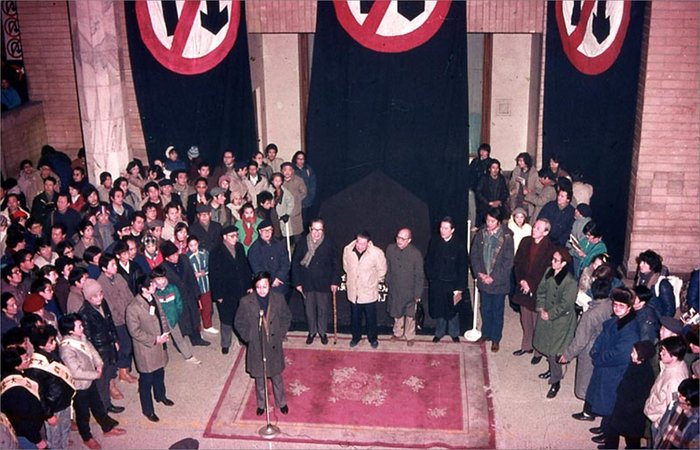

Gao Minglu speaking at the opening of

China/Avant Garde

Gao Minglu speaking at the opening of

China/Avant Garde

The National Art Gallery required that exhibitions be sponsored by official state units, so chief organizer Gao Minglu and his colleagues obtained sponsorship from seven publishers and art organizations. The exhibition agreement stipulated that there would be no performance art or sexually explicit content, although performance documentation was allowed. The call for works yielded three thousand entries from across China, from which about three hundred pieces by almost two hundred artists were selected. After three months of intense preparation, the show was ready to open on February 5

th

. It was the day before the Chinese New Year, a date chosen by authorities in hope of minimizing attendance. Because all work needed prior approval, a delegation of officials had reviewed the show. The exhibition filled six galleries on three floors with paintings, works on paper, photographs, installations and videos. The first floor featured large installations chosen to give a radical first impression. Despite the prohibition against performance, a few artists presented such work during the morning opening. Wu Shanzuan sold fresh shrimp from a box on the first floor, a comment on art becoming a commercial enterprise. Zhang Nian tried to hatch eggs sitting on the second floor. Li Shan washed his feet in a basin containing images of United States President Reagan. Wang Deren threw thousands of condoms and coins around the show. But the performance for which the exhibition is known was Xiao Lu’s shooting of her installation,

Dialogue

. A friend of Lu’s was arrested immediately, and she surrendered to authorities later that afternoon.

Xiao Lu shooting her installation

Dialogue

at the opening of the exhibition

Xiao Lu shooting her installation

Dialogue

at the opening of the exhibition

After the shooting, the exhibition was shuttered for three days, and the incident was widely reported in Chinese and international press. When the show reopened, there were large crowds, with visitors from well beyond the art-world. Two days later, the exhibition was closed due to a bomb threat. In the end, it was only open for eight days and two hours of the planned fifteen days. Following the show, the National Gallery fined the sponsors for the many transgressions, and prohibited their sponsoring exhibitions at the museum for two years. And after the repression of the democracy movement, the exhibition was cited as an example of the evils of reform.

"INFORMATION"

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1970

Cover of the catalog for

Information

, 1970

Cover of the catalog for

Information

, 1970

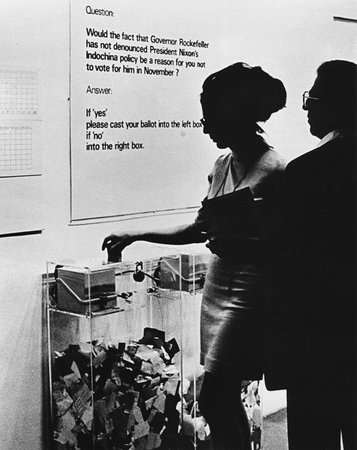

“Information” was an exhibition of radical content presented in the established Museum of Modern Art. The catalog featured photographs of Che Guevara and political demonstrations, and corporate sponsors Olivetti, ITT, and Xerox contributed the show’s technology. Its contradictions were announced at the exhibition entrance, where Hans Haacke’s

MoMA Poll

asked visitors to decide whether the former museum president’s not stating his opposition to the Vietnam War would be reason to vote against him for governor of New York. Almost 70 percent of those who replied voted “yes.” Haacke noted that, “David Rockefeller [chairman at the time] was not amused. Word had it that an emissary of his arrived at the Museum the next day to demand removal of the poll.”

Hans Haacke,

MoMA Poll

, 1970

Hans Haacke,

MoMA Poll

, 1970

While the MoMA Poll might have been the most confrontational work, the most controversial was John Giorno’s Dial-A-Poem, which offered the public twelve different readings a day accessible by telephone from both inside and outside the museum. In addition to the poems read by literary figures, there were statements by such radicals as Black Panther Kathleen Cleaver and Bernardine Dohrn of the Weathermen. In the press it was called “Dial-A-Revolutionary.” And with his show opening two months after the fatal shooting of student demonstrators at Kent State University, curator Kynaston McShine connected the full range of work in “Information” with radical politics. In the face of oppression around the globe, he stated, many artists had come to question the significance of “apply[ing] dabs of paint from a little tube to a square of canvas.” It is no wonder that the new museum director, John Hightower, walking the line between his sympathy for protestors and the need to mollify his conservative trustees, warned the museum’s governing board that much in the show was “tough, upsetting, and angry.”

The international roster of artists was a critical aspect of the exhibition, not only demonstrating the global use of conceptual strategies but also the existence of a McLuhanesque “global village” created by electronic systems of communication. McShine took this technology to have decentered the art world, a point suggested by the messages sent by Iain Baxter from Vancouver to a telex machine in the gallery. And of course there was much else to read, with Sacco beanbag chairs on which visitors could take a break from their reading.

Installation image of

Information

, 1970

Installation image of

Information

, 1970

The catalog functioned as a kind of exhibition site in itself. Apart from a short text by McShine and an extensive film list and bibliography of recommended readings, it consisted of pages solicited from artists—many referring to works other than those presented in the museum—and a long visual essay. Among the pages was a poster of dead bodies at the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam, with the question “And babies?” at the top and on the bottom the answer: “And babies.” Planned jointly by the Art Workers Coalition and the museum’s design department, it ultimately was nixed by museum trustees. But its inclusion in the catalog and in the exhibition suggests the growing capacity of museums to accommodate the radical gesture.

THE BULLDOZER EXHIBITION

Belyayevo, Moscow, 1974

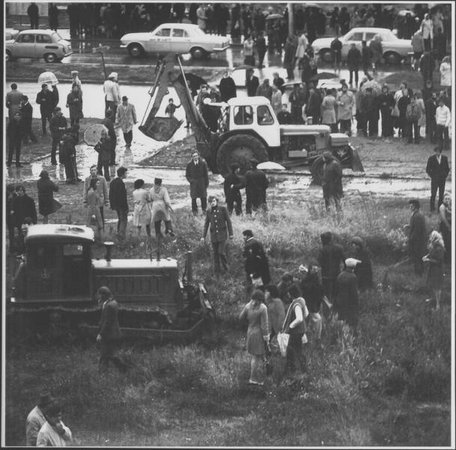

Due to the actions of the Soviet police, only a few photographs of the one-day exhibition have survived

Due to the actions of the Soviet police, only a few photographs of the one-day exhibition have survived

“The Bulldozer Exhibition” was a milestone in the history of nonconformist art in the Soviet Union. Its radical nature was not due to its content, but to its asserting the right to display work that deviated from the state definition of art. For the artists who planned a Sunday afternoon exhibition on an empty Moscow field, the violence they confronted came as a shock. But the authorities were no less surprised by the presence of foreign press, which turned “The Bulldozer Exhibition” into an international incident.

Although there had been a loosening of control over non Socialist-Realist art in the late 1950s, things changed with [General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union] Nikita Khrushchev’s 1962 denunciation of abstraction at the thirtieth anniversary exhibition of the Moscow Union of Artists in Manezh Exhibition Hall. Circumstances soon became more difficult for artists outside the official union, and they increasingly assembled in studios and apartments to show their work. In addition to such private gatherings, there were a small number of public exhibitions. One of these was organized in 1967 by collector Alexander Glezer at Moscow’s Friendship Club, although it was closed by the authorities within hours. Among the exhibiting artists was Oskar Rabin, the central figure in mounting “The Bulldozer Exhibition.”

Damaged work by Oskar Rabin and Lydia Masterkova

Damaged work by Oskar Rabin and Lydia Masterkova

On September 2, 1974, Rabin sent a letter to the Moscow City Council stating that a group of artists would exhibit their work at noon on September 15 in a field near the Belyayevo Metro station. The artists intended to hold the show with or without official permission, and they distributed an invitation for this “first fall viewing of paintings outdoors.” After discussion with the cultural affairs department, Rabin was informed that a space would not be provided for an exhibition but neither was their outdoor show forbidden.

When the artists and a crowd of a few hundred arrived at the site, they were met by more than fifty men. Claiming to be volunteers making a park for the neighborhood, they confiscated paintings and used bulldozers, dump trucks, and water-sprayers to destroy artworks and disperse onlookers. But the authorities had not expected the attendance of foreign press and diplomats, and in the melee four American journalists were assaulted. The next day an article on the incident appeared in the New York Times , and the U.S. government lodged an official complaint.

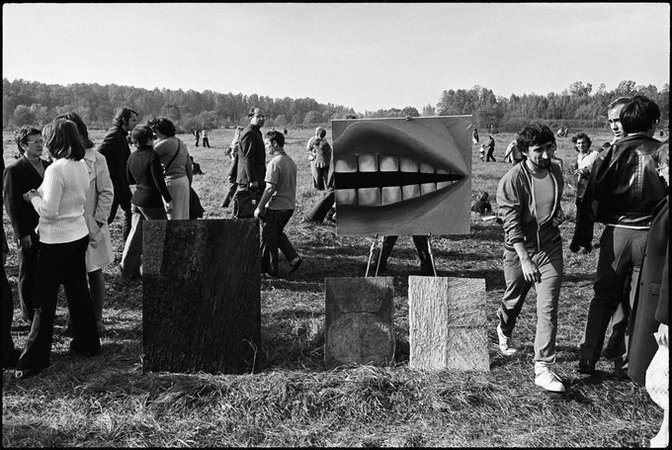

In response to international publicity and diplomatic pressure, and informed by Rabin and his associated that they would return to the same location on September 29, the government eventually granted permission for an exhibition on that date in Izmailovsky Park. About seventy artists participated, and the crowd on a beautiful Saturday afternoon was estimated at ten thousand. A French diplomat called it a Soviet Woodstock.

"Soviet Woodstock"

"Soviet Woodstock"