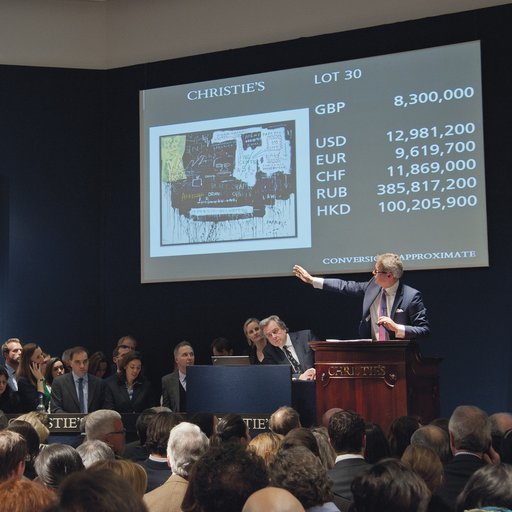

Though the new Chinese elite is well-represented in the Western art world—sitting in the audience of auction houses, at least—contemporary Chinese artists (beyond a few oft-repeated names) don't have nearly the international footprint as their American and European counterparts. (It's not for a lack of talent—the country boasts some of the largest and most competitive art schools in the world.)

In this excerpt from Phaidon'sVitamin P3, we take a closer look at three very different Chinese painters who are primed to claim the spotlight as they use their craft to explore the viscitudes of their nation's past, present, and future. Keep a sharp eye peeled for these upstarts at your next international art event—if you don't recognize their names now, they'll soon be inescapable.

CUI JIE

Born 1983, Shanghai, China. Lives and works in Beijing.

Cui Jie’s paintings are largely based on her continuous study of the architectural landscape in the three cities in which she has lived: Shanghai, where she was born and grew up, Hangzhou, where she attended the National Art Academy, and Beijing, where she currently lives and works. She observed at first hand the outstanding transformation that urbanization in Chinese cities has brought about, drastically changing the cityscape, with a proliferation of buildings, high-rises and plazas being erected throughout. Set in motion by the Chinese government’s relentless introduction of marketization since the 1980s, and in particular after 1989, this ruthless process of modernization standardized urban planning. The result was a formula of buildings that mix the influences and aesthetics of the Bauhaus with Soviet and Chinese communist styles, complemented by highly symbolic public sculptures taking centre stage in open squares and expansive plazas.

Cui’s paintings depict these urban architectural creations and presences, but from her distinct perspective. In her eyes, the sculptures that inhabit the different city squares appear superimposed on the buildings in the background. At some point, due to the effects of the depicted light, the surface of one merges with the surface of the other so that the sculpture becomes part of the architecture and the architecture part of the sculpture. Her large canvases present surreal architectural drawings, in which enlarged sculptures are grafted onto anonymous buildings found on city avenues, on street corners and in suburban areas. Cui recognizes that this explosion in urban development privileged speed and efficiency over stylistic concerns, resulting in odd changes, random interpretations and, at times, distortions of form and scale. In her work, the buildings are both non-specific and familiar; as are the sculptures which tend towards stereotypes such as birds in flight (be they eagles, pigeons, or cranes), arrangements of supported stainless-steel balls, flowing ribbons, or archetypal female and or athletic figures. Donning bright colors, her paintings weave together true-to-life images with imaginary ones to generate the effect of multiple exposures, spotted with marks that resemble the scratches on the surface of photographic negatives.

Overbearing office buildings, common-looking residential housing blocks, circular staircases, blue glass façades, unremarkable ceilings in parking lots, tiled floors, an abundance of columns and domes: all these architectural elements, and more, are juxtaposed in Cui’s paintings, with careful attention to composition and surface texture, as well as to the physical “architecture” built up on the painting by multiple layers of paint. This lengthy, painstaking process can take between several months and a year. The architectural and sculptural elements in her images are given sharp, clean edges through the use of sticking tape, removed once the paint has been applied. Their surfaces, which merge and blend into one another, are painted with steady, smooth brushwork that gives them a distinctively metallic shine and texture. The backgrounds, in contrast, are treated with a more abstract approach, in which the artist gives herself free rein, juxtaposing sometimes incongruous colors. Even so, despite the imaginary nature of these cityscapes, Cui Jie’s paintings perhaps remain one of the more perceptive and realistic depictions of the absurd and multi-layered excesses of a particular moment in Chinese urban development.

– Carol Yinghua Lu

YU HONG

Born 1966, Xi’an, China. Lives and works in Beijing.

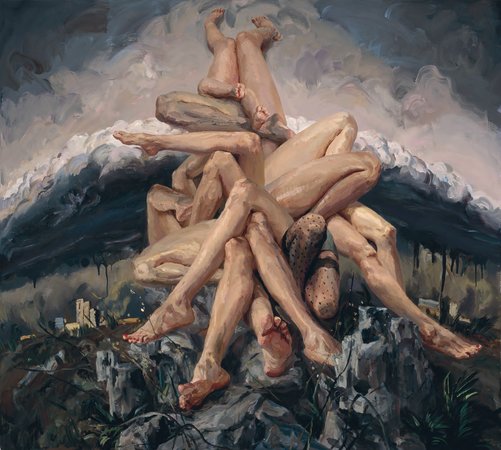

Yu Hong gained early fame as an exceptional realist painter in the 1980s while studying in the Oil Painting Department of the Central Academy of Art in Beijing. In 1991 she was featured in the landmark “New-generation Art Exhibition” at the Chinese History Museum in Beijing. This show gave visibility to a group of emerging artists who were attentive to their immediate surroundings and committed to portraying everyday life and people in a realistic way, drawing on the history of Socialist Realism but without the excessive dressing up of propaganda enforced in previous decades.

During this period, Yu Hong painted many portraits of her female friends, capturing their youth, pride, and emotions, usually in strange, boldly-colored settings. Amidst this wave of realism in China, her paintings, such as Food Shopping (2003), stood out for their intimate and unpretentious approach; self-referential figuration that seemed driven by sensitivity, fragility, dignity, and sincerity. After becoming a mother in 1994, the autobiographical nature of her paintings became even more prominent. To help herself adjust to motherhood, she began to paint portraits of herself, together with her daughter, at different times and in different situations, keeping a sort of visual diary of two different generations. Before long, Yu once again turned her gaze to the plight of other women. “Unemployed Girls” (2003) was a series of portraits she made of students, writers, artists, professors, and entrepreneurs, all women whose lives were affected by the drastic social and economic reforms in China.

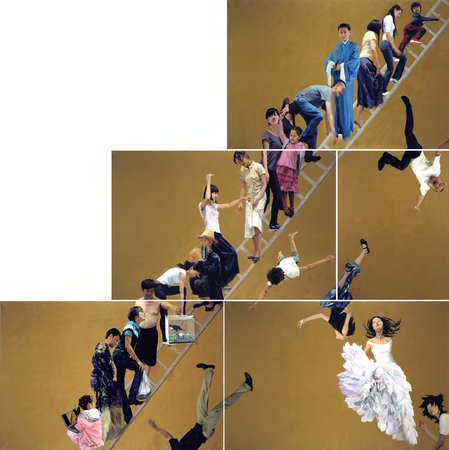

Ladder to Sky (2008) draws on the twelfth-century Ladder of Divine Ascent in Saint Catherine’s Monastery, near the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt. In Yu’s version, characters of varying ages and social standings climb up or fall off an extended ladder with no beginning or end. Typically in her paintings, her characters are portrayed in dynamic postures: bowing, twisting their bodies, sitting down, stretching their hands, pulling legs, lying flat, leaning forward, and so on. The result is a great sense of movement and theatricality, contrasting with the direct relevance of the people she chooses to depict.

– Carol Yinghua Lu

YUAN YUAN

Born 1973, Zhejiang, China. Lives and works in Hangzhou, China.

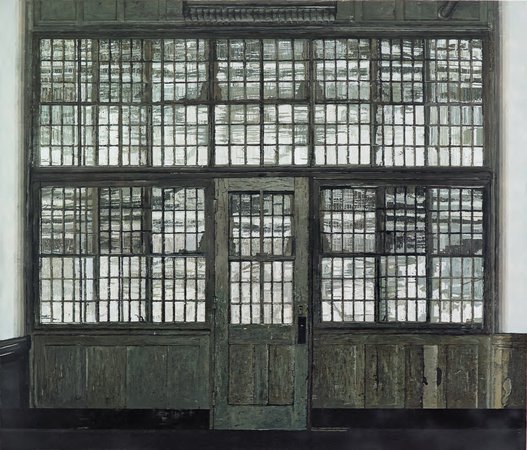

Yuan Yuan studied traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy when he was a teenager, and went through rigorous training in the techniques of socialist realist painting during his time as a student in the Oil Painting Department at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. His oil paintings are patient accumulations of painstaking brushwork, formally evocative of the works of the “Peredvizhniki”—sometimes referred to as “the wanderers”—exponents of traditional Russian realist art. Yet contrary to the Peredvizhniki painters’ preference for depicting people and their relationship to their surroundings, Yuan concentrates almost entirely on internal and uninhabited spaces. His paintings feature architectural interiors, at once elaborately lavish in style, yet rundown and deserted. In his work these abandoned interior settings, mostly from former private residences, are presented as ruins laid open to the prying and admiring eyes of the public. Traces of life still abound in these places, but the consistently dark colors and tones of Yuan’s depictions strike a mournful note.

Yuan cites the British artist Richard Long (b.1945) as an important point of reference, particularly his ability to venture into previously uncharted territories and activate the viewer’s awareness of little known places. In the same spirit of pioneering discovery, Yuan seeks out all kinds of inhabited spaces throughout his travels, but portrays them in an imaginary state of desertion. One wonders what has attracted the artist towards such forlorn scenes, but standing in front of, say, Daylights (2012), we are inevitably drawn to the obsessive details of the canvas, becoming immersed in the intricacies of light depicted as it shines through each pane of glass. A few subjects recur in this extensive body of work: decadent palatial settings and large mansion houses of a European style, complete with grand staircases, chandeliers and velvet curtains, a lavish bathhouse, steam room and lavatory, the opulent interiors of the Dream Liner ship, museums, doorways, and other architectural structures.

Additionally, tirelessly repeated patterns of mosaics, tiled walls, stained glass windows, books, patterned iron gates, and the like occur in many of Yuan’s paintings, seemingly revealing a desire to ground his images in geometric intricacy. Each pattern or unit is uniquely and thoroughly depicted, allowing the varying lights reflected off the myriad mosaics, the patterns and stains on each tile, the scratches and stains on each mirror, to be visible. Yet, once our fascination with the endless details contained in each of Yuan’s images is satisfied, we begin to see vividly that whatever he portrays—whole interiors or close-ups of architectural details—is treated like a still life, a memento mori constructed not of objects, but of buildings.

– Carol Yinghua Lu