One of the most significant recent developments in the Western art world has been a concentrated effort (on the part of certain figures and groups) to recognize, understand, and celebrate the work of artists hailing from outside the confines of Europe and the United States. Even so, the efforts of contemporary African artists remain tragically underrepresented in Western institutions and galleries, to the detriment of both the artists and their would-be audiences. In this excerpt from Phaidon’sVitamin P3, we take a closer look at three of the most important African painters working today. Though all under 40 years old, they’ve already proven themselves vital to the international conversation around contemporary painting—read on to find out why.

MELEKO MOKGOSI

Born 1981, Francistown, Botswana. Lives and works in New York.

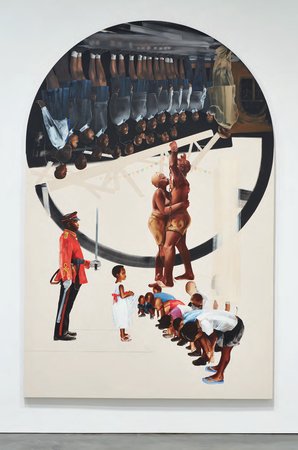

Meleko Mokgosi has stated that, “You have to know the history to painting, but you also have to know how to negate that history.” For the Botswana-born artist, locating the limits of the medium is a generative process. Mokgosi’s paintings are large, and when hung side by side (as they often are) they become, as some critics have noted, cinematic. Indeed his subjects appear like film extras waiting for instruction, adrift in negative space, seemingly without context. By using the language of cinema (such as storyboarding and framing) together with his unusual form of social realism, Mokgosi’s depictions of figures from African society and politics—usually floating within passages of raw empty canvas—are open to the possibility of a story, albeit an alternative and incomplete one. In their monumentality, his paintings allow the viewer to step into the pictorial space and therefore, by implication, into Mokgosi’s very own anthropology.

In dialogue with post-colonial discourse, Mokgosi’s work is primarily concerned with renegotiating issues of identity, nationhood, history, memory, and perception. Take, for instance, “Pax Kaffraria” (2010–14), a series comprising of eight “chapters” that together depict a landscape of figures from Southern Africa, including lions, dogs, cows, housekeepers, hunters, soldiers, politicians, and tribal chiefs. As the artist has explained, “Kaffraria comes from the ‘British Kaffraria,’ the name of a black settlement that the British established when they first arrived here. Today it’s code for ‘kaffir,’ the equivalent of the ’n word.’” The narrative that unfolds from one panel to the next makes the viewer not only a witness to a story, but also a participant (because looking is active) in the historical events that form the subject matter of this work. Importantly, Mokgosi’s documentary-like assemblages are often decontextualized images that have been sourced from photographs and news clippings from his homeland. As such, we might approach his work as contemporary history painting, where the chaos of the present is forwarded into the future.

Mokgosi uses painting to interrogate the concerns often associated with the genre: the limits of representation and role of the viewer. In Full Belly II (2014), part of the “Pax Kaffraria” series, a group of young girls in school uniforms stare out at us with crossed arms, semi-hidden beneath a thick black stripe. Is this stripe the school blackboard? And if so, does this imply that the blackboard is a symbol of pedagogical biases and censorship? In “Democratic Intuition” (2013-ongoing), a research-based series that tackles the question of democracy in Southern Africa, painting again moves closer to installation, where texts and images within round-shaped and rectangular canvases envelop the viewer’s space. The paintings emphasize a diversity of approaches to the notion of democracy, highlighting the dissonance between individual and collective thought, and showing those who are otherwise denied representation. Painting is here put in the service of those who are not usually seen or heard.

– Tom Francis

BLESSING NGOBENI

Born 1985, Tzaneen, South Africa. Lives and works in Johannesburg.

Q & A Unresolved Issues (Basquiat in my son), 2015

Q & A Unresolved Issues (Basquiat in my son), 2015

Fueled by the social injustices of post-Apartheid South Africa, Blessing Ngobeni’s large-scale mixed media paintings serve as scathing condemnation of the country’s political elite, and can be read as a direct attack on the structures of power. Incorporating a range of found materials from newspaper clippings to cut-outs from the pages of glossy magazines, Ngobeni’s paintings are dense with naked or heavily pregnant figures and a range of weird and wonderful characters, from strange machine-like hybrid forms and automatic rifles to eyeless hyenas. Using a palette of predominantly grey, black, white, blue, red, and yellow, his frenzied psychedelic paintings are inspired by his own nightmarish visions of a world in turmoil. Borrowing from the language of Surrealism, the anarchy of Dada and the figurative violence of Neo-Expressionism, particularly the work of the American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–88) whom he referenced in works such as Q & A Unresolved Issues (Basquiat in My Son) (2015), Ngobeni’s painting is characterized by obsessive mark making and littered with overt political references.

His personal story is one of triumph over adversity. Born in the Limpopo province in northern South Africa, as a toddler he was left in the care of an abusive uncle. By the age of ten, he was living as a street urchin in Alexandra, an impoverished township in Johannesburg. Following an incident with the police at age fourteen, Ngobeni was sentenced to a term in prison, which ultimately proved his saving grace. To escape the daily drudgery of prison life, he retreated into his own world and started sketching. After his release at the age of twenty, Ngobeni began making disturbing, layered paintings. In Fallen Tyranny (2011), a terrifying cartoon-like character wearing a pair of clownish boots holds a severed head in one hand; the figure’s own head is made up of multiple faces and silhouettes. In turn, this head is dominated by the inverted face of Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s controversial President, sporting his signature glasses, albeit with red dots as eyes. Ngobeni’s depiction of this colorful character who has played a key role in South Africa’s recent history—embroiled in a series of scandals and corruption charges that would have ended the careers of most politicians—expresses his disgust and disillusionment with corrupt politicians.

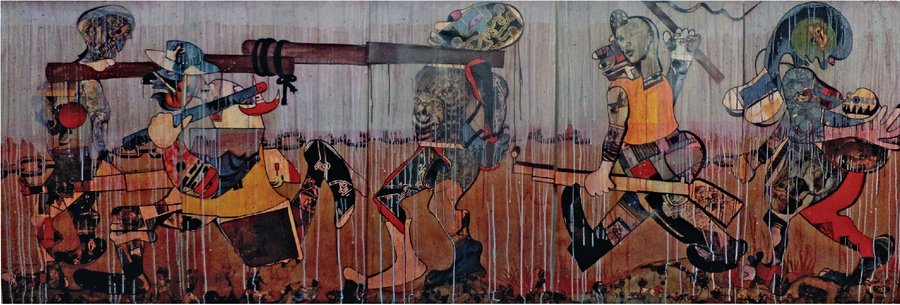

Democratic Slave Master, 2013

Democratic Slave Master, 2013

Red dots in lieu of eyes are a recurring motif in Ngobeni’s work, and are suggestive of the corrupting nature of power, whilst inverted heads symbolize the as yet unrealized dream of peace and prosperity articulated by Nelson Mandela, whose ideals are literally turned upside down. In Democratic Slave Master (2013), a procession of surreal figures with bulging breasts and exaggerated bodily forms are armed with rifles and other crude weapons—a potent symbol of South Africa’s armed struggle against Apartheid. The torso of the shackled central figure includes an image of two cheetahs, symbols of stealth and speed, whilst his flaccid phallus points to his impotency. In such multi-layered paintings as these, Ngobeni has created a space in which he is free to exercise his desire to critique, attack, and comment on the machinations of power that continue to hold South Africa in the grip of poverty, violence, and the ugly reality of political repression.

– Alona Pardo

NJIDEKA AKUNYILI CROSBY

Born 1983, Enugu, Nigeria. Lives and works in Los Angeles.

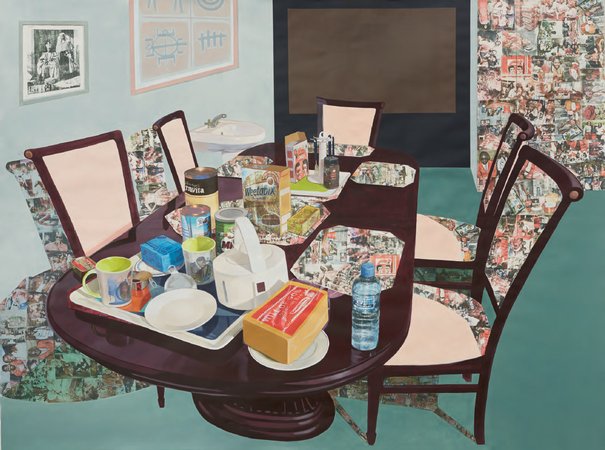

Tea Time in New Haven, Enugu, 2013

Tea Time in New Haven, Enugu, 2013

Rooted in the history and traditions of painting, Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s practice contains ideas of hybridity in both form and content. Formally, her canvases are striking combinations of painting, drawing, printmaking, and collage, comprising acrylic mixed with colored pencil, pastel, charcoal, Xerox transfer, and marble dust. Likewise, her imagery brings together her diverse experiences living in Nigeria and on the east and west coasts of the United States, merging recollections of a range of experiences, both real and imagined. The results are complex, multi-layered canvases that weave together references to personal events, popular culture, and art history. The artist currently lives and works in Los Angeles, where she finds similarities to her home town of Enugu, Nigeria, in terms of the weather, light, color palette (in particular the hot yellows and warm chartreuse greens), and temporary architectural structures—such as the use of lightweight, translucent scrims to demarcate space—all of which feature in her recent works.

Figures play a central role in Akunyili Crosby’s practice, which includes intense studies of individuals (as seen in the series “The Beautyful Ones” from 2014), couples (depicting herself and her husband), and groups of multi-generational families gathered around sitting rooms and dining tables. Her interior scenes are marked by formal and casual living spaces featuring combinations of realistically-rendered American and Nigerian domestic products set on crowded tables, as in Tea Time in New Haven, Enugu (2013), pointing to her experiences of both of these cultures and the fluidity of exchange between the two.

Akunyili Crosby’s work is typified by her bold use of blocks of color to organize the canvas and designate space, with simplified figures and interior features arranged within shallow planes. Her interest in printmaking influences the pared down approach to defining space and presenting information in distinct fields. Akunyili Crosby has also utilized printmaking to create a unique visual language: swathes of images from Nigerian magazines and other popular media—which she avidly collects and covets as a way of referencing her home—are presented through Xerox transfer, silkscreens, and other printing techniques. This repetition conveys the patterned fabrics and textures of carpets, wallpaper, draperies and clothing within her motifs.

Yet it is the history of painting that has had the greatest influence on Akunyili Crosby’s compositions and approach to making art. As a student at Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, she studied Diego Velásquez (1599–1660) and Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), as well as other Spanish School artists, the influence of which is particularly visible in “The Beautyful Ones” in both the posture of the figures and their arrangement in space. Contemporaries such as Kerry James Marshall (b.1955) and Chris Ofili (b.1968) also serve as inspiration, themselves both deeply indebted to painting traditions while at the same time departing from them. Their influence is evident in Akunyili Crosby’s experimentation with composition, including her signature mixture of sweeping gesture and intense detail. Her highly constructed images, such as Nwantinti (2012), take viewers on an optical journey through layers of paint, glazes, patterns, and textures—her scope at times as broad as to denote a wall, doorway or bed, at others as finely calibrated as to convey an individual sequin on a dress or jewel on an earring.

– Rochelle Steiner