Phaidon's new title Going Once tracks 250 years of Christie's auction house history through 250 seminal auctions, dotted with odd and unexpected items, spectacularily high prices, and more than a few eccentric stories of intrigue. Naturally, the book is filled with record-breaking lots, from which we've chosen the most compelling and historically significant to showcase below. Don't be surprised if some of your favorite works and artists make the list—auction houses are in the business of selling masterpieces.

1. THE FAITHFUL FRIEND

When the painter Diego Velázquez travelled to Italy in 1649, the main purpose of his journey was to buy and commission works of art for his king, Philip IV of Spain. During the two years he spent in Rome, however, Velázquez would achieve something considerably more: he produced some of the greatest portraits of his career.

Besides painting members of the papal court, the artist was also commissioned to produce a portrait of Pope Innocent X—the notoriously wily and unattractive Pope, who deigned to sit for just one day. Perhaps the greatest work to be produced at this time, though, was Velázquez’s informal portrait of his own assistant, Juan de Pareja, who accompanied him on his Italian travels. Often referred to as Velázquez’s “slave,” de Pareja was painted with immediacy, insight and sympathy, so much so that viewers at the time were astounded by the startling likeness.

Velázquez and de Pareja returned to Spain in 1651, but de Pareja’s portrait was sold and remained in Italy. It was acquired by the British ambassador to Italy, Sir William Hamilton, in Naples in 1776. During the Napoleonic Wars the Velázquez, along with other works from Hamilton’s collection, was sent to Britain on Nelson’s flagship, HMS Foudroyant, in 1801. Hamilton, who was heavily in debt, sold his collection in March that year. His pictures fetched £6,000 ($26,280; equivalent to £408,200/$591,787 today), with the Velázquez selling for £40 19s ($180; equivalent to £2,785/$4,035 today). Ten years later, it was acquired by the 2nd Earl of Radnor.

The portrait remained in England until 1970, when it was auctioned on behalf of the 8th Earl of Radnor and became the first painting to sell for more than £1m at auction. The art critic Richard Cork, who was at the sale, recalled: “The atmosphere was extraordinary. The bidding outflew all expectations. It started at £315,000, and took just 130 seconds. It was finally knocked down for a staggering £2,310,000, almost tripling the previous world auction record for a painting. Even the most hardened dealers sitting in the audience breathed gasps of disbelief. Then there was a spontaneous burst of applause. The auctioneer left his rostrum, the painting was hastily removed, and sheer pandemonium broke out.” It is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

2. THE MOST FAMOUS LITTLE DANCER IN THE WORLD

When the wax Petite danseuse de quatorze ans (Little Dancer aged Fourteen) by Edgar Degas was first exhibited, at the sixth Impressionist exhibition in 1881, it scandalized visitors. The sculpture, a portrait of the plucky young dancer Marie van Goethem, was considered so drab and lifelike that one critic described it as a “rat from the opera learning her craft with all of her evil instincts and vicious inclinations.” Today, posthumous bronze casts of this sculpture reside in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, and Tate Modern, London, and it has become one of the most famous artworks in the world.

Degas loved the ballet. He haunted the Paris Opéra, studying performances and sketching the dancers backstage, and on one occasion declaring that his soul was like a worn pink-satin ballet shoe. However, by 1880, he was going blind, and so he took to sculpting the dancers in wax rather than painting them.

After the artist’s death in 1917, a collection of his wax sculptures was found in his studio, including the little dancer. His family made bronze casts of the originals, and these have been in great demand ever since. In 1988, this early copy was auctioned as part of the collection of film producer William Goetz and his wife Edith, the daughter of movie mogul Louis B. Mayer. Edith had bought the work in the late 1940s for her neo-Georgian home near Hollywood. It sold for over $10m, a record price at the time for any piece of sculpture.

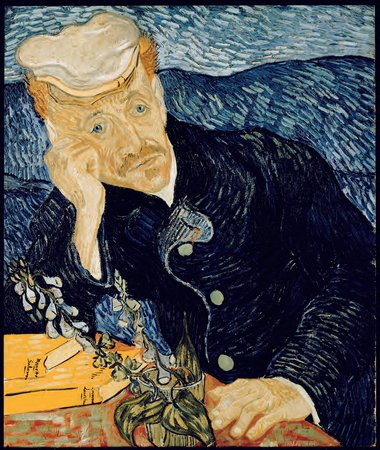

3. PICTURE OF MELANCHOLY

In 1990, Vincent van Gogh’s powerful portrait of the physician who cared for him in the last few months of his life broke all records to become the most expensive painting ever sold at auction. It was bought for $82.5m by Ryoei Saito, a Japanese paper manufacturer, who purchased it during a two-day spending spree in which he also bought the small version of Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette (1876) for $78.1m.

The sale of the Portrait of Dr Gachet provided another twist in the story of this melancholy picture. Painted just before Van Gogh committed suicide in 1890, it was described by the artist as “weary with the heartbroken expression of our time.” It was first sold by the widow of Van Gogh’s brother Theo to the ambitious art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, and the painting went on to hang in Frankfurt’s Städelsches Kunstinstitut.

Subsequently classified as “degenerate art” under Nazi cultural policy, the painting was removed from the museum’s collection in 1937 and was acquired by Hermann Goering for his personal collection. It was saved from destruction only when Franz Koenigs, a German banker living in Amsterdam, bought the painting from Goering and passed it on to the Jewish philanthropist Siegfried Kramarsky who shipped it to America.

The painting emerged on to the open market at a critical moment in early 1990. Rumors of an impending financial crash were rife and buyers were getting nervous, not least those from Japan, who had dominated the auction houses for the previous few years but were now starting to pull out. Saito’s phenomenal bid flew in the face of such widespread pessimism, and when the gavel came down in the auction room, people leapt to their feet and cheered with relief. It seemed—at the time—that the rumors of financial disaster were unfounded. Sato died in 1996 and despite rumors of him having the painting cremated with him at his funeral being retracted, Portrait of Dr Gachet has not been seen since the auction. It still stands to this day as the world record price at auction for any work by the artist.

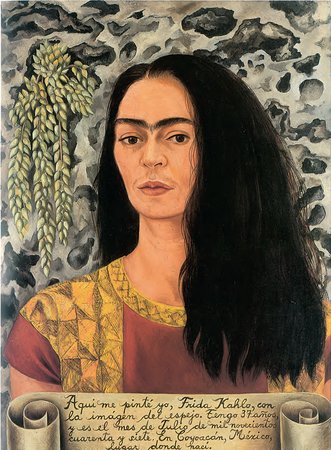

4. EYES WIDE OPEN

The first Latin American work of art to exceed $1m at a Christie's auction was a small painting by the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.* The record sale was surprising because it occurred during the financial recession in 1991, yet there were good reasons for the price. Kahlo created relatively few paintings in her short life, and Mexico’s policy of national patrimony (applied to Kahlo’s works since 1984) meant that her paintings could no longer be exported. This resulted in there being very few works by the artist on the open market.

Kahlo began painting in 1925 while convalescing from a near-fatal bus crash that resulted in her spine being broken in three places. The self-portraits she made over the next thirty years captured the tortured spirit of a woman who was in continuous physical pain. “She lived dying,” said Leo Eloesser, her doctor and close friend.

Kahlo died in 1954, but the demand for her paintings continued to escalate, particularly in the 1980s, when identity politics became a potent theme in the art world. Feminists saw Kahlo as an icon for her taboo-breaking subject matter; she had rejected traditional perceptions of beauty by depicting herself with a thick unibrow and downy mustache. Added to this was her famously tumultuous marriage to the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera (1896–1957), a union that fascinated many.

Self-Portrait with Loose Hair was painted in 1947, a year in which Kahlo had undergone a series of grueling operations. She was forty years old, though the painting’s inscription states her age as thirty-seven. Unlike many of her portraits, in which her long hair is braided or tied back, in this work it is left loose, alluding to the vulnerability of her emotional and physical state. Her ability to deal with the frailty of the body, with life and death and with female suffering has long fascinated collectors, and is a major reason why competition to secure her work remains fierce to this day.

5. THE REAL DA VINCI CODE

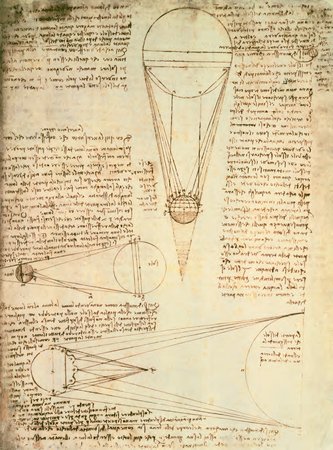

The record for a manuscript sold at auction was set on November 11, 1994 when Bill Gates, then chairman of Microsoft, purchased the Codex Hammer, a rare Leonardo “notebook,” for over $30m.

Being a lateral thinker and innovator, Gates is fascinated by Leonardo da Vinci, one of the great creative polymaths of the Renaissance. The Codex Hammer comprises seventy-two loose leaves brought together to form a notebook, written by Leonardo between 1506 and 1510. In it he speculates and discourses on many subjects, from astronomy and meteorology to geology. Everything in the notebook is linked by the theme of water: how it moves and how it can be manipulated. The pages are packed with over 350 of Leonardo’s drawings, rendered in chalk and brown ink, as well as his tiny “mirror” writing, which reads from right to left in reverse.

In 1690, this notebook was discovered among the papers of Guglielmo della Porta, a sixteenth-century Milanese sculptor and student of Leonardo’s work. By 1717, it had made its way into the collection of Thomas Coke, the future Earl of Leicester, and it remained in his library at Holkham Hall in Norfolk, for 263 years, where it was named the Codex Leicester. In 1980, the American industrialist and philanthropist Armand Hammer acquired the manuscript from Christie’s for a record-breaking $5.1m (£2.2m; equivalent to $12.1m/£8.4m today) and renamed it Codex Hammer. Just fourteen years later, the manuscript was back on the market.

Before the sale in 1994, the manuscript travelled to Seoul, Tokyo, Milan and Zurich, building anticipation in each city. On the day of the sale, bidding opened at $5.5m (£3.6m) but quickly rose to over $30m. The final, anonymous bid was greeted with a round of applause.

Gates, who later announced himself as the anonymous buyer of the Codex Hammer, said that he found knowledge itself to be “the most beautiful thing.” He has since had the Codex scanned into digital image files, and a comprehensive CD-ROM was released in 1997. The manuscript continues to travel the world and is put on public display in a different city every year.

6. THE DREAM COLLECTION

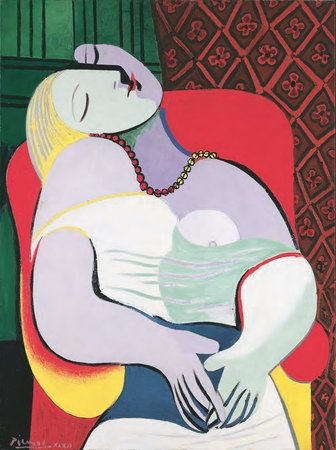

Over the course of fifty years, Victor and Sally Ganz assembled one of America’s greatest collections of modern twentieth-century art. This low-key Manhattan couple focused on five artists: Pablo Picasso, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, and Eva Hesse. Most discerningly, they “never bought to be comprehensive,” wrote the Picasso scholar Michael FitzGerald. “They bought because they remained fascinated by an individual work of art.” In 1941, the couple made their first major purchase, for $7,000 (equivalent to $109,000 today): Picasso’s Le rêve (The Dream), a portrait of the artist’s young lover Marie-Thérèse Walter. Sally likened acquiring this seductive, erotically charged work to “falling in love.” Twenty-six years later, in 1967, the last Picasso to enter the Ganz collection was Femme assise dans un fauteuil (1913), one of the great Cubist paintings.

Le rêve is one of the Spanish artist’s most popular and enduring images. It shows Marie-Thérèse napping in an armchair and is celebrated for the brilliant intensity of the pigments, its clean contours and its erotic content (a phallic outline is visible on the upper side of Walter’s face). In 1932, the year in which it was painted, it featured in Picasso’s first major mid-career retrospective at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris.

The insightful taste with which the Ganzes had built their collection—that included Hesse’s Vinculum I (1969) as well as Stella’s Turkish Mambo (1959)—coupled with the allure of so many modern and post-war masterpieces, generated huge interest in what was to be one of Christie’s most important single-owner sales. The New York Times reported that from the moment Christopher Burge, then chairman of Christie’s America and the evening’s auctioneer, opened bidding at the fifty-eight-lot sale, “the salesroom became a sea of bobbing paddles and waving agents taking calls from telephone bidders.”

Hesse’s Vinculum I fetched $1.2m, while Le rêve sold for $48.4m, setting an auction record for Picasso. Another major Picasso also came under the hammer that evening: Les femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’) (1955). It was bought for $31.9m, more than twice its high estimate of $12m. In May 2015 the painting set a record for the most expensive work ever sold at auction, when it achieved $179.3m at Christie’s New York.

7. HEAVEN IN A WILD FLOWER

At the start of her long career, Georgia O’Keeffe created a unique style of painting that synthesized abstraction and her personal observation of the natural world. Her large-scale paintings of flowers, which she began in the early 1920s, are close-up images that are at once monumental and extremely intimate. When they were first exhibited they caused a sensation, but most of the criticism—both positive and negative—missed the point. Her critics spoke of her work in terms of sexuality, a reading that O’Keeffe herself always denied. Her intention was to get people to look at things they normally would not notice. She remarked: “In a way, nobody sees a flower, we haven’t the time … so I said to myself I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

Painted in 1928, Calla Lilies with Red Anemone is one of a series of calla lilies, the flower with which O’Keeffe is most closely associated. Explaining that it was her habit to work with an idea for a long time, she said: "It’s like getting acquainted with a person, and I don’t get acquainted easily." Each painting in the series is strikingly individual, with the white lilies arranged in various ways and set against different colors.

Calla Lilies with Red Anemone, which is larger than most, introduces another flower as a vibrant contrast in texture and shape as well as color. O’Keeffe designed its frame herself, and she put her star motif and signature on the back—something she very rarely did, believing her works were so clearly identifiable that they did not need to be signed. When the painting was sold at Christie’s in 2001, it fetched over $6m, then a world record for O’Keeffe, and the record price at auction for any work by a woman artist at that time.

8. WHEN NIGHT BECOMES DAY

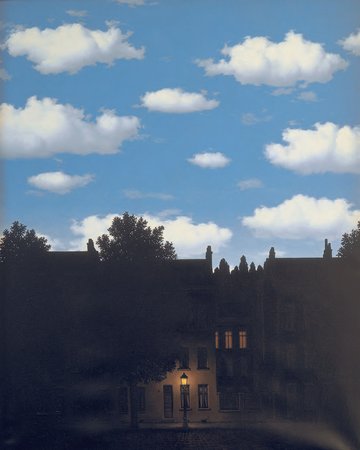

The Belgian SurrealistRené Magritte said he wanted his paintings to “show what the mind can say and which was hitherto unknown.” Magritte employed techniques that recall the characteristics of Freudian dream interpretation: bizarre juxtapositions, and irrational arrangements of perspective, lighting, and atmosphere. Creating an element of subversion that so many of the Surrealists propagated, Magritte explored his subconscious—constantly awakening and reviving dreams.

Magritte would return regularly to the same subjects, as in L’empire des lumières (Empire of Light). This uncanny combination of night and day—darkened trees and buildings, with a glowing street lamp, beneath a blue sky with fluffy clouds—preoccupied him more than most. Over a fifteen-year period between the late 1940s and the mid-1960s, he made seventeen oils and ten gouaches of this image, each with subtle differences: more buildings, varying formats, less densely clouded skies.

Magritte confessed that he had always felt “the greatest interest in night and day, without however having any preference for one or the other. This great personal interest in night and day is a feeling of admiration and astonishment.” The subject similarly appealed to the self-appointed high priest of Surrealism, André Breton, who had written as early as 1923 in his poem The Egret: “If only the sun were to come out tonight.” Breton later wrote a catalogue essay on Magritte, in which he describes the double-take effect on the viewer in L’empire des lumières: “The violence done to accepted ideas and conventions is such (I have this from Magritte) that most of those who go by quickly think they saw the stars in the daytime sky.”

Introduced by Alexander Iolas to many of the Surrealist artists, including Magritte, Dominique and Jean de Menil acquired a vast collection of their paintings, sculptures and objects. Reluctant to be labelled as “collectors,” the de Menils were actively and personally engaged with their art and emotionally powerful patrons who fostered the development of many artists. In 1950, they donated the second completed version of L’empire des lumières to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It met with great critical and public acclaim, and in 1952 the de Menils commissioned Magritte to paint this work, the fourth completed version. It was sold in 2002 for over $12.6m, and remained the artist’s record price at auction for the following twelve years. The new record, at $12.9m, was set in 2014 by Le beau monde (1962).

9. WATERLILY WORLD

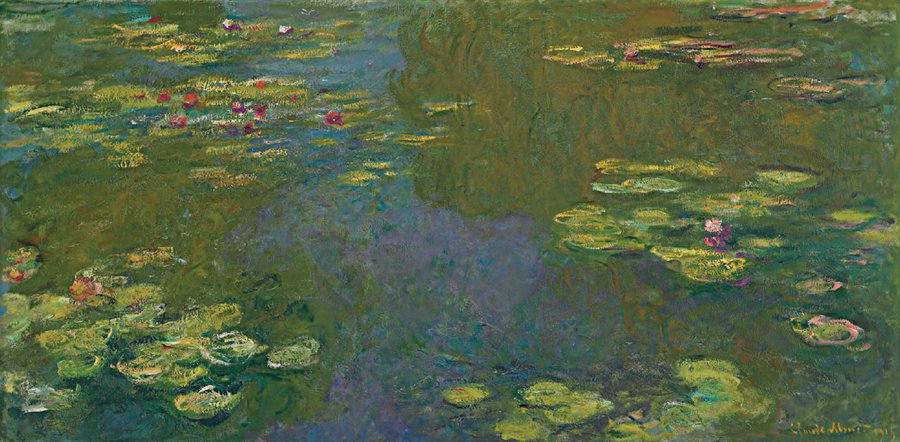

Claude Monet, Le bassin aux nymphéas (Waterlilies), 1919. Sold on June 24, 2008 for $80,379,590.

Claude Monet, Le bassin aux nymphéas (Waterlilies), 1919. Sold on June 24, 2008 for $80,379,590.

Le bassin aux nymphéas is part of Claude Monet’s celebrated waterlily series, which culminated in the “grandes décorations” he designed for the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris (1914–26). In 2008 the oil painting broke the world auction record for a Monet, prompting those who packed the King Street salesroom to break into spontaneous applause.

Monet re-landscaped the grounds of his house in Giverny, west of Paris, to create a water garden filled with exotic flowers. He then devoted the later part of his life to painting waterlilies. Playing with reflections and the effects of light on water, he made a series of immersive paintings that exerted a lasting influence on other artists, in particular the Abstract Expressionists.

What made Le bassin aux nymphéas so unusual and so coveted by collectors in 2008 was that this late painting, produced at the height of Monet’s creative powers, was signed and dated. Monet regarded his waterlily paintings as a work in progress, and guarded them jealously. He signed only five and sold four (one of which now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

When Le bassin aux nymphéas was offered for auction in London, it had not been seen in public for eighty years, having been in the private collection of the American industrialist J. Irwin Miller and his wife, Xenia. The record price reflected an understanding that this rarest of paintings, made at a critical moment in the artist’s long career, might never be seen in a salesroom again.

10. RAPHAEL’S MUSE

In 1508, as Michelangelo began working on the Sistine Chapel ceiling at the Vatican, the twenty-five-year-old Raphael was summoned to the court of Pope Julius II to help with the redecoration of the papal apartments. Part of his assignment was to paint frescoes for the Pope’s library and private office, the Stanza della Segnatura. The series of four works that Raphael produced is widely considered to be his masterpiece. This drawing was for a section of a wall depicting Mount Parnassus, the home of Apollo, and the nine Muses.

Raphael’s exquisite Head of a Muse (c.1510) is an auxiliary cartoon, a type of preparatory drawing that allowed the artist to experiment with particularly important or tricky details of his design. It was made by pressing powdered chalk through the pricked outlines of the original drawn cartoon on to a fresh sheet of paper, leaving guiding lines that Raphael then drew over, adapting the design as his ideas evolved. Less cumbersome than the full-scale cartoon, which was probably 9.75 ft x 6.5 ft, the small drawing acted as a reference tool during the painting of the fresco, and remains a unique record of Raphael’s thinking during the final stages of creating Mount Parnassus.

When Head of a Muse was sold in 2009, it set a new world record for a work on paper, soaring beyond the £12m–16m estimate. As reported at the time, “two bidders were clawing it out” in what was described as “a knockdown fight.” When the gavel finally struck, the winner was an anonymous telephone bidder who paid more than $48m for the drawing.

[related-works-module]

*The first work of Latin American art to exceed $1m at any auction was another painting by Frida Kahlo, Diego y Yofrom 1949, which sold at Sotheby's in 1990 for $1.4 million.